Fiscal conservatism

Fiscal conservatism is a political position (primarily in the United States of America) that calls for lower levels of public spending, lower taxes and lower government debt. Fiscal conservatism may also support limited periods of higher taxes in order to lower the public debt. It can include any or all levels of government, federal, state and local. Fiscal conservatism is typically justified in terms of economic efficiency (it assumes the private sector is more efficient than the public sector), and in moral terms with high spending, budget deficits, and high debt seen as indicators of corruption. In opposition to corruption fiscal conservatism develops classic themes of republicanism that emerged in the era of the American Revolution. Fiscal conservatism rejects the Keynesian policy of deficit spending.[1]

"Fiscal conservatism" is distinct in American politics from social conservatism, which concentrates ion issues of personal morality regarding family life and sexual norms. It is closer to the libertarian approach to drastically limited government. Republicans and Democrats both make claims to fiscal conservatism, though both parties may honor its principles more in the breach than in the observance, and both use the idea as a cudgel to attack their opponents as much as a guide to their own proffered policies.

Conservative fiscal policies

One of the familiar slogans associated with fiscal conservatism since the Reagan years is "starve the beast," a phrase which suggests a policy approach of limiting the size of government by limiting appropriations for government programs. The assumptions underlying this policy range from, at its best, that government is less capable than individual citizens in caring for people's needs, and, at its worst, that government is inefficient and corrupt. Earlier in the 1960s, Milton Friedman first proposed greater concentration on monetary policy rather than the reigning fiscal Keynesian approaches of the time.

Fiscal conservatism in U.S. History

A major cause of the American Revolution was "No Taxation without Representation." The Americans insisted that their historic rights as Englishmen entitled them to a voice in setting tax policies, which Britain denied. The issue was not the tax itself or its size, but approval by elected representatives. The Continental Congress borrowed heavily and did not practice fiscal conservatism.

Early United States

The Republican party of Thomas Jefferson supported a weak central government and a low-tax approach, in sharp opposition to the high-spending, high-taxation policies of Hamilton and his dominant Federalist Party. Jeffersonians opposed Hamilton's plan to pay off the debts owed by the states for the expense of the American Revolution, because some of the debt was held by financiers and speculators (who they said did not deserve payment) rather than the original holders. Hamilton passed his legislation and set up tariffs and a highly controversial whiskey tax to pay the debts. When western farmers (who shipped their crops as whiskey) revolted, President George Washington led militia units (provided by state governors) to quell the rebellion without bloodshed. When Jefferson became president he dropped the whiskey tax, kept the tariffs, and grew the national debt by purchasing Louisiana in 1803.

James Madison, James Monroe, and John Quincy Adams were all elected as Republicans, but after the fiscal disasters of the War of 1812, they came to support most of the Federalist position, realizing that the nation needed a central bank and a steady income flow from tariffs.

Republican Era

In 1854 a new fiscally liberal political party emerged, the Republican Party, which borrowed heavily to finance the Civil War, raised taxes and tariffs, and promoted heavy spending in aid to railroads, colleges, farmers, and schools. The Democrats demanded fiscal conservatism, as represented by Grover Cleveland and his cadre of Bourbon Democrats.[2]

Early 20th century

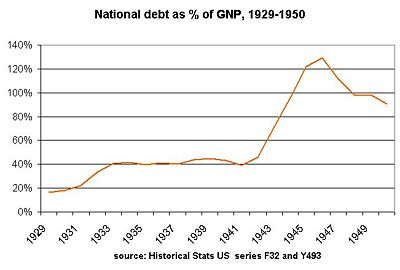

During the 1920s, President Calvin Coolidge and his Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon cut taxes and spending, and reduced the national debt. Their pro-business economic policy were credited for the successful period of economic growth known as the "Roaring Twenties." After the great crash of 1929, however, Coolidge's successor Herbert Hoover took the blame. Hoover increased spending and increased taxes, but because of falling revenues the national debt mushroomed relative to GDP.[3]

New Deal

During the 1930s Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal was opposed by many conservatives because it expanded the scope of the federal government, and regulated the economy. In general Roosevelt did not raise taxes above the high levels Hoover had set; the national debt changed little from 1933 to 1940 as a proportion of GDP.[4]

Roosevelt's Treasury Secretary, Henry Morgenthau, Jr. believed in balanced budgets, stable currency, reduction of the national debt, and the need for more private investment. Morgenthau accepted Roosevelt’s double budget as legitimate–that is a balanced regular budget, and an “emergency” budget for agencies, like the WPA, PWA and CCC, that would be temporary until full recovery was at hand. He fought against the veterans’ bonus until Congress finally overrode Roosevelt’s veto and gave out $2.2 billion in 1936. Morgenthau's most notable achievement was the new Social Security program; he managed to reverse the proposals to fund it from general revenue and insisted it be funded by new taxes on employees. Morgenthau insisted on excluding farm workers and domestic servants from Social Security because workers outside industry would not be paying their way.[5]

In World War Two there was broad agreement for heavy taxes, with conservatives insisting that the income tax base be broadened to include the great majority, rather than the 10% who before 1942 paid all income taxes.[6]

After 1945 fiscal conservatism was most prevalent in the Conservative coalition, including Midwestern Republicans and most southern Democrats, especially Senators Harry F. Byrd, and Walter F. George.

The Reagan Era

Fiscal Conservatism was rhetorically promoted during the presidency of Ronald Reagan (1981-1989). During his tenure, Reagan pushed through economic policies which became known as Reaganomics. Rooted in a belief in supply-side economics, Reagan cut income taxes, raised social security taxes, deregulated the economy, and propounded a tight monetary policy to stop inflation. Reagan favored reducing the size and scope of government because he considered it to be conducive to inefficiency and corruption; he especially attacked welfare. He proposed greatly increased defense spending (which he got), reduction in income taxes (which he got), and reductions in domestic spending (which he did not get). The result was a large increase in the national debt, economic prosperity, and rapid growth. Reagan also achieved a compromise on Social Security that reduced long-term federal spending.[7]

However, by the end of Reagan's second term the national debt held by the public rose from 26% of Gross Domestic Product in 1980 to 41% in 1989, the highest level since 1963. By 1988, the debt totaled $2.6 trillion. The country owed more to foreigners than it was owed, and the United States moved from being the world's largest international creditor to the world's largest debtor nation as investors around the world rushed to send their money to the U.S.[8] Under Democrat Bill Clinton the federal government ran a budget surplus and the debt went down. The George W. Bush policy was to return the surplus to taxpayers by lowering federal income taxes, even as spending increased, especially for the Iraq war. Democrats attacked the Bush policy as a violation of fiscal conservatism.

Notes

- ↑ Critchlow, "The Political Control of the Economy: Deficit Spending as a Political Belief, 1932-1952," (1981)

- ↑ Brownlee, Federal taxation in America: A short history. (1996).

- ↑ William J. Barber, From New Era to New Deal: Herbert Hoover, the economists, and American economic policy. (1985)

- ↑ Stein, Presidential Economics: The Making of Economic Policy From Roosevelt to Clinton (1994)

- ↑ * Zelizer, "The Forgotten Legacy of the New Deal: Fiscal Conservatism and the Roosevelt Administration, 1933-1938." (2000).

- ↑ Leff, "The Politics of Sacrifice on the American Home Front in World War II," (1991)

- ↑ Stein, Presidential Economics: The Making of Economic Policy From Roosevelt to Clinton (1994)

- ↑ See[1]