Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1955-1975) was an international Cold War conflict that killed 3.8 million people, in which North Vietnam and its allies fought U.S. forces and eventually took over South Vietnam, forming a single Communist country, Vietnam.

For other wars in the same region, see Vietnam wars.

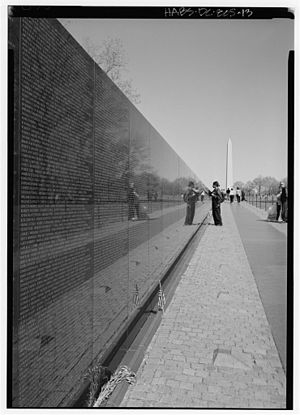

Impact on American culture

A significant portion of Baby Boomers, the U.S. generation who were young during the protracted Vietnam War, grew up seeing continual bloody footage of active combat on television every night. As the war progressed, an avalanche of young people in the U.S. protested against the war, resulting in considerable domestic turmoil. The protests were in part because of the military draft that sent unwilling young men to their likely death or maiming, but also in part because young people did not see the aims of the war as worth the cost. This pitted the young across the nation against the World War II generation, who viewed encroachments by Communists during the Cold War as an important continuation of the wars fought by the U.S. since 1940. To prevent protests during the Iraq War, the U.S. military stopped allowing TV journalists to film actual combat.[1]

Because the U.S. lost the Vietnam War, by the 1980's it became unpopular even to refer to it, and the press began avoiding the topic, while surviving veterans went without adequate benefits for post-traumatic treatment and, unable to cope with life, became homeless by the thousands. This phenomenon was the main subject of Sylvester Stallone's 1982 action film First Blood, which was panned by critics as too violent even though only a single person died (due to his own stupidity). Several subsequent Stallone films about First Blood's main character, Rambo, were indeed mindlessly violent, unlike the original film, which was conceived and written by Stallone (who played Rambo) in protest for public abandonment of Vietnam veterans. This film also depicted the aftermath of U.S. military having sprayed the jungles of Vietnam with Agent Orange, a herbicide containing dioxin which resulted in many exposed soldiers and civilians later getting cancer, the horror of which had barely begun to be recognized by the public in 1982. The only prior major film about the Vietnam War was Francis Ford Coppola's 1979 Apocalypse Now, an adaptation of Joseph Conrad's story “Heart of Darkness” to Vietnam. Coppola's film was indeed violent, a direct and nightmarish depiction of the devastation of war, but critics praised it, and it won multiple awards, in contrast to Stallone's First Blood which had touched a nerve with its social criticism of American culture.

Strategic Summary

The war had four distinct periods characterized by the nature of the conflict and the nationality of the combatants: a period of civil war (1957-1964), the Americanization (1964-1969), the Vietnamization (1969-1973), and the end (1974-1975).

The Vietnam War originated from the unresolved antagonisms implicit in the Geneva Accords (1954) and French and U.S. Cold War ambitions, namely to "contain" the spread of communism. The Geneva Accords promised elections in 1956 to determine a national government for a united Vietnam. Neither the United States government nor Ngo Dinh Diem's State of Vietnam signed anything at the 1954 Geneva Conference. With respect to the question of reunification, the non-communist Vietnamese delegation objected strenuously to any division of Vietnam, but lost out when the French accepted the proposal of Viet Minh delegate Pham Van Dong,[2] who proposed that Vietnam eventually be united by elections under the supervision of "local commissions".[3] The United States countered with what became known as the "American Plan," with the support of South Vietnam and the United Kingdom.[4] It provided for unification elections under the supervision of the United Nations, but was rejected by the Soviet delegation and North Vietnamese.[5]

Due to the stalemate, North Vietnam created two organizations. The National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam (NLF) was a political organization to establish civil government for the South Vietnamese regions controlled by its military arm, the Viet Cong (VC). The political/military actions of the NLF and VC against the Diem regime in South Vietnam, and Diem's escalation against the NLF/VC, essentially started a civil war. The climatic event of the civil war period was the Buddhist crisis in 1963 ending in the assassination of Ngo by a CIA-backed operation authorized by President Kennedy.

Americanization of the war began by the Johnson Administration in 1964 following the Gulf of Tonkin Incident. The U.S. began sending ground combat troops in 1965, and troop strength continued to escalate through 1968. The climatic event during the Americanization period was the Tet Offensive. Following a change in presidential administrations in the 1968 election, President Nixon followed a strategy of de-escalation and "Vietnamization" of the conflict, while also escalating the conflict through incursions into Cambodia and Laos, and bombings of North Vietnam. At various times, the U.S. and South Vietnamese forces were joined by South Korean, Filipino, New Zealand, Thai and Australian troops.

As Vietnamization went into effect, and the Paris Peace Talks completed in 1972, the U.S. role changed again South Vietnam fought its own ground war, with U.S. ground combat troops withdrawing between 1968 and 1972, with the last air attacks in 1972. After that, the U.S. provided limited replacements of supplies, and maintained a large, diplomatic Defense Attache Office that monitored the RVN until the fall of South Vietnam in 1975.

After the U.S. withdrawal, South Vietnam collapsed after being invaded by the DRV in 1975. Memorable pictures of desperate people clinging to helicopters reflect the evacuation of diplomatic, military, and intelligence personnel, and some Vietnamese allies. Other than for the immediate security of the evacuation, no U.S. combat troops or aircraft had been in South Vietnam since 60 days after the signing of the peace treaty in Paris.

The war exacted a huge human cost in terms of fatalities. The most detailed demographic study calculated 791,000 to 1,141,000 war-related deaths for all of Vietnam,[6] while the Vietnamese government claimed that over 3 million Vietnamese died during the conflict.[7][8] 195,000-430,000 South Vietnamese civilians died in the war.[9][10] 50,000-65,000 North Vietnamese civilians died in the war.[11][9] The Army of the Republic of Vietnam lost between 171,331 and 220,357 men during the war.[12][9] The official US Department of Defense figure was 950,765 communist forces killed in Vietnam from 1965 to 1974. Defense Department officials believed that these body count figures need to be deflated by 30 percent. In addition, Guenter Lewy assumes that one-third of the reported "enemy" killed may have been civilians, concluding that the actual number of deaths of communist military forces was probably closer to 444,000.[9] Some 200,000–300,000 Cambodians,[13][14][15] 20,000–200,000 Laotians,[16][17][18][19][20][21] and 58,220 U.S. service members also died in the conflict.

U.S. replaces France

After the Geneva accords of 1954 split the former French Indochina into the Republic of Vietnam (South) and Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North), France no longer had colonial authority. After certain procedural matters were resolved in early 1955, the United States took up a major role in training and funding what was now the Army of the Republic of Vietnam in the South. U.S. intelligence collection personnel had been in the area since the latter part of the Second World War. In 1954, Edward Lansdale, a United States Air Force officer seconded to the Central Intelligence Agency, came to Saigon under the cover of Assistant Air Attache leading the Saigon Military Mission, which was a CIA operation whose immediate activities included sending Vietnamese personnel north, to set up stay-behind intelligence collection and covert action teams for future use.

It has been argued, certainly with some justification, that the U.S. unwisely supported the French before 1954, and still had a pro-French view after 1954. Part of this was due to U.S. diplomatic strategy that saw French cooperation in Europe as essential to NATO and to Western stability, and taking a pro-French position in the former Indochina obtained cooperation from France. The Vietnamese were not seen as important, in Cold War terms, in the 1940s and 1950s, even though, perhaps ironically, it was Japanese expansion into French Indochina that triggered U.S. economic warfare against Japan, and eventually the Japanese decision for war in 1941.

Later, the U.S. would support anticommunist Vietnamese, never neutralists.

The strategic balance

While Vietnamese Communists had long had aims to control the whole of Vietnam, the specific decision to conquer the South was made, by the Northern leadership, in May 1959.[22] The Communist side had clearly defined political objectives, and a grand strategy to achieve them; there was a clear relationship between long-term goals and short-term actions, within their strategic theory of dau tranh. Some of their actions may seem to be from Maoist and other models, but they have some unique concepts that are not always obvious.

Apart from its internal problems, South Vietnam faced difficult military challenges. On the one hand, there was a threat of a conventional, cross-border strike from the North, reminiscent of the Korean War. In the 1950s, the U.S. advisors focused on building a "mirror image" of the U.S. Army, designed to meet and defeat a conventional invasion. [23] Ironically, while the lack of counterguerrilla forces threatened the South for many years, the last two blows were Korea-style invasions. With U.S. air support, the South were able to largely repel a conventional invasion by North Vietnam. The 1975 invasion which defeated the South was not opposed by U.S. forces.

Early U.S. noncombat advisory and support roles

Harry S. Truman, as soon as the Second World War ended, was under great pressure to return the country to normal civilian conditions, and he demobilised rapidly to release funds for domestic spending. There were no such pressures to demobilize, however, on Josef Stalin and Mao Zedong. Truman has been blamed for "losing" Eastern Europe and China, but it is less clear what could have been done to stop it. The decision to cut military commitment came home to roost in the Korean War, when Truman had few forces to dispatch.

From 1955, the U.S. took over the role of training and significantly funding the Southern Army of the Republic of Viet Nam (ARVN). In 1959, the first U.S. advisers to go into combat in the area were in Laos, not Vietnam. With a negotiated settlement to the Laotian civil war in 1962, U.S. attention shifted to South Vietnam. Communications intercepts in 1959, for example, confirmed the start of the Ho Chi Minh trail and other preparation for large-scale fighting. This information may not have been fully shared with the South Vietnamese, due to security concerns over the intelligence methods used to get the information.

Interactions of South Vietnamese & U.S. politics

After the French colonial authority ended, Vietnam was ruled by a nominally civilian government, led by first Bao Dai and then, from 1954, by Ngo Dinh Diem; neither were elected. Communist statements frequently spoke of it as a U.S. "puppet" government, although the Northern government had not been elected and had little more claim to democratic legitimacy. Both governments were clients of the different major sides in the Cold War.

Diem was strongly anti-communist, but authoritarian, and there were increasing protests against his rule. He was a Catholic in a Buddhist-majority country, but gave preference to Catholics. While personally ascetic, he tolerated a serious level of corruption in the government.

Effect on military efficiency

Not only under Diem, appointing officers to the command of military units, and also to posts in the separate hierarchy of district and province chiefs, often were made as political loyalty as the first criterion, possibly bribes or favors at the next, and military proficiency sometimes as a last consideration. Officers were shifted from post to post, in the interest of breaking up potential coup plots.

In practice, the most powerful military positions were the commanders of the four Corps tactical zones (CTZ), also known as military regions. Even though a CTZ was geographic, and province and district chiefs were usually military officers, the province/district reporting went through the Ministry of the Interior rather than the military Joint General Staff.

Especially powerful units might, in the interest of interfering with coups, be shifted from one chain of command for another. At the Battle of Ap Bac, for example, the potent armored personnel carriers (APC) had been shifted from the operational control of the military commander to that of the province chief. Before the unit commander would commit his resources to battle, at the urging of a U.S. adviser to the division commander, the commanding officer of the APC company had to obtain province chief as well as military approval, significantly increasing the time before this unit could intervene in battle.

Conflicting goals

Vietnamese and U.S. goals were also not always in complete agreement. Until 1969, the U.S.A. was generally anything opposed to any policy, nationalist or not, which might lead to the South Vietnamese becoming neutralist rather than anticommunist. There is evidence that the U.S. supported attempts to replace governments that were considering forming a neutralist coalition that might include the National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam, a communist-dominated opposition. The Cold War containment policy was in force through the Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Johnson Administrations, while the Nixon administration supported a more multipolar model of detente.

While there were still power struggles and internal corruption, there was much more stability between 1967 and 1975. Still, the South Vietnamese government did not enjoy either widespread popular support, or even an enforced social model of a Communist state. It is much easier to disrupt a state without common popular or decision maker goals.

Instability

The association of the U.S. with the RVN government, however, was sufficiently strong that instability there both reflected adversely on the U.S. role, and seen as interfering with the fight against Communism. While Diem ruled between 1954 and 1963; there followed a period of frequent changes of government, some lasting only weeks, between 1964 and 1967, until moderate stability came in 1967.

Protests generally called the Buddhist crisis of 1963, which also involved other Vietnamese sects, such as the Cao Dai and Hoa Hao, were a major disruption by June. These protests were seen by the U.S. as strengthening the Communist insurgency, and, after rejecting earlier initiatives for a military coup, agreed that Diem had to go.

In November 1963, Diem was overthrown and killed in a military coup. The United States was aware of the coup preparations and, through CIA officer Lucien Conein, had given limited financial support to the generals involved. There is no evidence that the U.S. expected Diem, and his brother and closest political adviser, Ngo Dinh Nhu to be killed; U.S. Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. had offered him physical protection.

The leaders of the November coup were replaced by a nominal civilian government really under military control, which was overthrown by yet another military coup (involving some of the same generals) in January 1964.

Between 1964 and 1967 there was a constant struggle for power in South Vietnam, and not just from within the military. Several Buddhist and other factions often derived from religious sects, which became involved in the jockeying for political power, such as the Cao Dai and Hoa Hao. Even the Vietnamese Buddhists were not monolithic, and had their own internal struggles. At varying times, sects, organized crime syndicates such as the Binh Xuyen, and individual provincial leaders had paramilitary groups that affected the political process; while the Montagnard ethnic groups wanted autonomy for their region. William Colby (then chief of the Central Intelligence Agency's , Far Eastern Division in the operational directorate) observed that civilian politicians "divided and sub-divided into a tangle of contesting ambitions and claims and claims to power and participation in the government." [24] Some of these factions sought political power or wealth, while others sought to avoid domination by other groups (Catholic vs Buddhist in the Diem Coup).

After a period of overt military government, there was a gradual transition to at least the appearance of democratic government, but South Vietnam neither developed a true popular government, nor rooted out the corruption that caused a lack of support.

Covert operations

Well before the Gulf of Tonkin and overt operations, there were a number of covert operations, some ostensibly with U.S. advisers to South Vietnamese crews, and some, especially in Laos, of which no public announcement was made. Certain of these operations became public in postwar historical analyses, official announcements at the time, or press reporting that eventually was confirmed.

US activity before independence

Still, there was U.S. activity in Southeast Asia, which grew out of covert operations directed more at China. In August 1950, the CIA bought the assets of Civil Air Transport (CAT), an airline founded after the Second World War by Gen. Claire L. Chennault and Whiting Willauer. While CAT continued commercial operations, it acted as a CIA "proprietary", or covert support organization under commercial cover. CAT aircraft, for example, dropped personnel and supplies over mainland China during the Korean War.[25] CAT later became part of Air America.

When Dwight D. Eisenhower succeeded Truman as President in 1952, after a campaign that had attacked Truman's "weaknesses" against communism and in Korea, he formulated a strong policy of containing Communism. There was much sensitivity over "softness" exemplified by the excesses of Senator Joe McCarthy. While the Eisenhower Administration avoided becoming too enmeshed in the French problem of the Indochinese revolution, airlift was provided by CAT pilots. United States Air Force C-119 Flying Boxcar transports, repainted with French insignia. CAT trained the crews at Clark Air Force base in the Philippines, and then flew the aircraft to Gia Lam Airport in Hanoi. They made airdrops to French forces in Laos between May and July. Eventually, CAT flew logistics missions to Dien Bien Phu, in March to May 1954; one aircraft was shot down and others damaged.

Laos

After France left the region, the Royal Lao Government (RLG) quietly asked the United States to replace the former French funding of the Lao military, and to add military technical aid from the increasingly active Communist insurgency, the Pathet Lao. This assistance started in January 1955, directed by a new part of the Embassy, with the nondescript name Program Evaluation Office (PEO). At first, the PEO simply dispensed funds, but took on a much larger role in 1959.

When the first direct military assistance began in July 1959, the PEO was operated by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency using military personnel acting as civilians. [26] CIA sent a unit from United States Army Special Forces, who arrived on the CIA proprietary airline Air America, wearing civilian clothes and having no obvious US connection. These soldiers led Meo and Hmong tribesmen against Communist forces. The covert program was called Operation Hotfoot. At the US Embassy, BG John Heintges was designated the head of the PEO. [27]

In April 1961, Chief of Staff of the Air Force Curtis LeMay’s began to approve certain covert operations, such as JUNGLE JIM. He denied them to the press. They were, however, a response to President Kennedy's challenge for the military to develop a force capable of fighting the “Communist revolutionary warfare”, regarded as proxy wars for the U.S. and Soviet Union. One of the first to respond to the call for combat control volunteers[28]

CIA, MACV-SOG and OPPLAN34A

John F. Kennedy approved, on May 11, 1961, a Central Intelligence Agency plan for covert operations against North Vietnam. These included ground, air, and naval operations. Eventually, the operations were transferred to officially military control, in a unit, MACV-SOG, principally reporting to MACV but with an approval chain that often ran to the White House.

CIA naval operations, under Tucker Gougelmann, in 1961,[29] starting with motorized junks. The first motor torpedo boats were transferred to CIA in October 1962. At the end of 1962, raids began.

They received their improved Norwegian Nasty-class boats in 1963.[30] These more sophisticated craft were crewed by Norwegian and German mercenaries as well as South Vietnamese; U.S. Navy SEALs conducted the training in Danang.

MACV-SOG was formed in January 1964, and took over the "modest" CIA maritime operation, based in Danang, now given the cover name Naval Advisory Detachment, actually branch OP37 of MACV-SOG. The attacks, under the command of MACV-SOG, were actually carried out by the Coastal Security Service of the RVN Strategic Technical Directorate.

So, at least a year before the Gulf of Tonkin, there had been some raids against North Vietnam. Independent of MACV-SOG, the U.S. Navy began to conduct signals intelligence patrols for the National Security Agency, close to North Vietnam but in international waters. These were called the DESOTO patrols, and used overt U.S. Navy destroyers, with a van packed with electronics and technicians mounted on their decks.

On the night of July 30, 1964, four MACV-SOG boats shelled North Vietnamese shore installations, after a series of earlier maritime operations. The North Vietnamese went on high naval alert.

On July 31, 1964, there was a DESOTO patrol.[31] The timing after the MACV-SOG operation may have been coincidental, although there have been suggestions that the increased North Vietnamese activity was a rich environment for SIGINT collection. There is no strong indication that the DESOTO patrols were trying to provoke North Vietnamese response; they carefully stayed in international waters and were fully identifiable as U.S. ships.

U.S. buildup and overt combat involvement

This section focuses on the period when U.S. forces became involved in large-scale, direct combat. Wherever possible, the national-level decisions that went into a change of military action will be presented, but, in a number of situations, an action may have been the result of a perceived need to "do something" rather than having a direct effect on the enemy. Such decision-making style is not unique to this period. George Kennan, considered a consummate diplomat and diplomatic theorist, observed that American leaders, starting with the 1899-1900 "Open Door" policy to China, have a

neurotic self-consciousness and introversion, the tendency to make statements and take actions with regard not to their effect on the international scene but rather to their effect on those echelons of American opinion, congressional opinion first and foremost, to which the respect statesmen are anxious to appeal. The question became not: How effective is what I am doing in terms of the impact it makes on our world environment? but rather: how do I look, in the mirror of American domestic opinion, as I do it?[32]

Even when leaders' goals are sincere, the need to be seen as doing the popular thing can become counterproductive. There were many times, in the seemingly inexorable advance of decades of American involvement in Southeast Asia, where reflection might have led to caution. Instead, the need to be seen as active, as well as the clashes of strong egos, separate the needs of policy from the dictates of politics. The personalities of different Presidents and key advisers all had an effect. Many, but by no means all, of the key political decisions were under Johnson, but Presidents from Truman through Ford all had roles.

Although Americans died in supporting South Vietnamese involvement beginning in 1962, the greatest U.S. involvement was from mid-1964 through 1972. U.S ground troops began reducing in 1968 and much more sharply in 1969. So, much of the detailed U.S. political action with other countries will be in Joint warfare in South Vietnam 1964-1968, Vietnamization, and air operations against North Vietnam.

Vietnam's climate has a major effect on warfare, especially involving vehicles and aircraft. Major operations usually took place in the dry season. While the most southern parts tend to have a generally tropical climate, there are two major climactic periods:

- Monsoon season of heat, rain, and mud, with limited mobility (May to September)

- Warm and dry conditions (October to March)

Combat support advisory phase

John F. Kennedy and his key staff, came from a different elite than that which had spawned the Cold Warriors of the Eisenhower Administration. While the form was different, a militant anti-Communism was underneath many of the Kennedy Administration policies. [33] Its rougher operatives had a different style than Joe McCarthy, but it is sometimes forgotten that Robert Kennedy (RFK) had been on McCarthy's staff. [34]

Where Republicans during the Truman and Eisenhower administrations blamed Democrats who had "lost China", the Kennedy Administration was not out to lose anything. The first covert operations in the region began in the Eisenhower Administration, but Kennedy increased both operations in Laos and Vietnam.

Intensification

Guerrilla attacks increased in the early 1960s, at the same time as the new John F. Kennedy administration made Presidential decisions to increase its influence. Diem, as other powers were deciding their policies, was facing disorganized attacks and internal political dissent. There were conflicts between the government, dominated by minority Northern Catholics, and both the majority Buddhists and minorities such as the Montagnards, Cao Dai, and Hoa Hao. These conflicts were exploited, initially at the level of propaganda and recruiting, by stay-behind Viet Minh receiving orders from the North.

U.S. personnel went into the field with ARVN personnel starting in 1962. The term "adviser" was popular but not always accurate. While many U.S. personnel indeed did advise their counterparts, and U.S. forces did not take a direct combat role, a substantial part of field activity was devoted to tactical airlift of ARVN troops, and a wide range of technical support. The first American soldier to die in combat was not with ARVN infantry, but part of a signals intelligence team, doing direction finding on Viet Cong radio transmitters in the field, whose team was ambushed.

Th Battle of Ap Bac, fought on January 2, 1963, did involve both U.S. advisers to ARVN commanders, as well as U.S. aviation support. John Paul Vann was the senior tactical adviser, and his outrage about ARVN performance both stimulated aggressive investigative journalism, as well as infuriating the U.S. command.

Deterioration and reassessment

By November 1963, after Diem was killed, there was mixed feelings among the JCS if covert operations alone could have a significant effect. [35] Chief of Staff of the Air Force GEN Curtis LeMay pushed his JCS colleagues for "more resolute, overt military actions." He was joined by Commandant of the Marine Corps GEN David Shoup, and gained stronger support from the Army and Navy chiefs, GEN Earle Wheeler and ADM David McDonald. ADM Harry Felt, commander of U.S. Pacific Command, also believed covert actions alone would not be decisive. LeMay said "we in the military felt we were not in the decision-making process at all [Chairman of the JCS Maxwell] Taylor might have been but we didn't agree with Taylor in most cases."[36]

To senior civilian officials, with the Joint Chiefs receiving it via Secretary of Defense McNamara, Johnson stated his policy decision in classified National Security Action Memorandum (NSAM) 273, of November 26, 1963. The key point was the U.S. goal was to strengthen South Vietnam to win its own contest; the U.S. expected to begin to withdraw troops. "It remains the central object of the United States in South Vietnam to assist the people and Government of that country to win their contest against the externally directed and supported Communist conspiracy. The test of all U.S. decisions and actions in this area should be the effectiveness of their contribution to this purpose.

He made pacification of the Mekong Delta the highest priority, but also ordered planning for increased yet deniable activity against North Vietnam. "With respect to Laos, a plan should be developed and submitted for approval by higher authority for military operations up to a line up to 50 kilometers inside Laos, together with political plans for minimizing the international hazards of such an enterprise." These operations would change from CIA to MACV control. A "favorable influence", but no operations in, Cambodia was desired.

A high priority was producing "as strong and persuasive a case as possible to demonstrate to the world the degree to which the Viet Cong is controlled, sustained and supplied from Hanoi, through Laos and other channels."[37]

The JCS responded to NSAM 273 with a January 22, 1964 memorandum to McNamara. Significant differences with the Presidential decision, which emphasized assisting South Vietnam, was a JCS goal of "victory" as the goal of U.S. military operations.

Gulf of Tonkin Incident

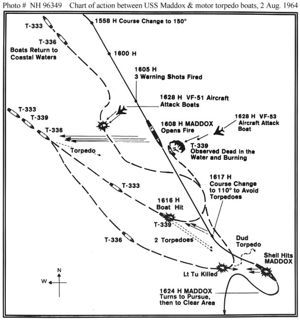

Track chart of USS Maddox (DD-731) and three North Vietnamese motor torpedo boats, during their action on 2 August 1964. Attacks by aircraft from USS Ticonderoga (CVA-14) are also shown.

On August 2, 1964, a DESOTO Patrol destroyer (USS Maddox, DD-731) was believed to have been approached, and possibly fired upon, by the North Vietnamese. After much declassification and study, the incident largely remains shrouded in what German military theorist Carl von Clausewitz has called the "fog of war," but questions have been raised about whether the North Vietnamese believed they were under attack, about who fired the first shots, and, indeed, if there was a true attack. There has not been a clear indication from the North Vietnamese if they thought the DESOTO and 34A operations were part of the same programs, and, if so, if destroyer-sized vessels represented an escalation. Later on the 2nd, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Maxwell Taylor, ordered that DESOTO patrols should not be made at the same time as 34A operations.

There is some question as to whether the second patrol (increased to two ships with air cover) was actually attacked, or if there were merely North Vietnamese warships in their area. Declassified NSA intercepts of North Vietnamese communications, on the 4th, show considerable confusion on the DRV side. Operating under Presidential authority, Johnson launched Operation PIERCE ARROW (air strikes against North Vietnamese naval facilities and the oil refinery at Vinh) on the evening of the 4th (Washington time), and gave a speech regarding the same approximately 90 minutes before the Navy aircraft reached their targets.[31]

President Johnson asked for, and received, Congressional authority to use military force in Vietnam after the Gulf of Tonkin Incident, which was described as a North Vietnamese attack on U.S. warships. Congress did not "declare war," which is its responsibility under the Constitution; nevertheless, it launched what effectively was at the time the longest war in U.S. history, and even longer if the covert actions before the August 1964 Gulf of Tonkin situation are included. The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, although later revoked, was considered by Lyndon Johnson as his basic authority to conduct military operations in Southeast Asia. It serves as an example of how outright declarations of war have become extremely rare since the Second World War.

Beginning of air operations

A U.S. Air Force Boeing B-52F-70-BW Stratofortress drops Mk 117 750 lb (340 kg) bombs over Vietnam, circa 1965-1966.

Immediately after the Gulf of Tonkin Incident, there was a period of retaliation for specific attacks, Operation FLAMING DART, and then a steady but incremental pressure under Operation Rolling Thunder operations against North Vietnam. There was also extensive air support overtly inside South Vietnam, and, at different times, in Laos and Cambodia; some of these are discussed above in the section on covert activity.

From a current doctrinal standpoint, these campaigns should be evaluated according to an examination of air operations relying on a planning model at the level of operational art. This model distinguishes effectiveness, or the results of the campaign, from the tactical aspects of weapons effects. Several factors need to be considered to determine effectiveness. The campaigns in Laos and Cambodia were far more effective than Operation Rolling Thunder, as they were not executed as a subtle means of "signaling", but had clear objectives measurable in military terms. The objectives here, as well as in Operation Linebacker I, were military. Operation Linebacker II also was effective, but it had well-defined objectives at the level of grand strategy: compellence to return to negotiations. [38]

- What conditions are required to achieve the objectives?

- What sequence of actions is most likely to create those conditions?

- What resources are required to accomplish that sequence of actions?

- What is the likely cost or risk in performing that sequence of actions?

Major ground combat phase

- See also: Vietnam War military technology

Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, who had been appointed by Kennedy, became Johnson's principal adviser, and continued to push an economic and signaling grand strategy. Johnson and McNamara, although it would be hard to find two men of more different personality, formed a quick bond. McNamara appeared more impressed by economics and Schelling's compellence theory [39] than by Johnson's liberalism or Senate-style deal-making, but they agreed in broad policy. [40]

They directed a plan for South Vietnam that they believed would end the war quickly. Note that the initiative was coming from Washington; the unstable South Vietnamese government was not part of defining their national destiny. The plan selected was from GEN William Westmoreland, the field commander in Vietnam.

This model regarded the enemy forces in the field as the opposing center of gravity, as opposed to the local security and development of pacification. The enemy, however, had a different idea of centers of gravity; see Vietnamese Communist grand strategy.

Over time, the U.S. developed tactics increasingly appropriate to the environment and foe, given the Westmoreland's assumption that the center of gravity was the enemy main force. Some of the early operations included:

- Operation ATTLEBORO [r]: Add brief definition or description

- Operation Starlight [r]: The first offensive operation, in the Vietnam War, by the United States Marine Corps with the Army of the Republic of Vietnam, which pre-empted a Viet Cong attack on the logistics base at Chu Lai [e]

- Operation CEDAR FALLS [r]: 19-day Vietnam War "search and destroy" mission in January 1967 in the "Iron Triangle" area northwest of Saigon. [e]

- Operation JUNCTION CITY [r]: A large "search and destroy" beginning in late 1967 and lasting for 72 days, following Operation CEDAR FALLS north of Saigon, with a 35,000 soldier force of South Vietnamese and United States troops [e]

There were many such operations, variously by U.S. only, U.S. and ARVN, and ARVN forces. The term "search and destroy" was often used to describe ground operations against Viet Cong and People's Army of Viet Nam troops.

The UH-1 "Huey", as well as other types of helicopters, are iconic of the Vietnam War. The full capabilities of units with integrated helicopter support were shown by the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile) at the Battle of the Ia Drang and the Battle of Bong Son.

These operations continued, some joint with ARVN troops and some by U.S. and third country forces alone. Australian units, integrated into large U.S. forces, were highly regarded. Less mobile but potent divisions came from South Korea and Thailand.

Immense fire support, from ground and air platforms, supported these operations. Close air support both from fighter-bombers and early armed helicopters was common, but new techniques came into wide use. ARC LIGHT was the general code name for operations using B-52 heavy bombers against targets in South Vietnam. The term grew to encompass B-52 operations against targets in Cambodia and Laos, principally against the Ho Chi Minh trail. B-52 use in the major Operation Linebacker I and Operation Linebacker II operations against North Vietnam are generally not considered ARC LIGHT missions; see the respective operations.

There were also technical measures to clear jungle, both mechanical and chemical. See Vietnam War ground technology.

Unquestionably, Westmoreland's approach inflicted immense casualties on the enemy forces. Even so, the North Vietnamese seemed willing to accept them. During the second half of 1967, the North Vietnamese intensified operations in the border regions of South Vietnam, in at least regimental strength. Unlike the usual hit-and-run tactics used by communist forces, these were sustained and bloody affairs. Beginning at Con Thien and Song Be in October 1967, then at Dak To

There had long been fighting in the Khe Sanh area, but the North Vietnamese greatly intensified their attacks in early January 1968, before the Tet Offensive. They continued operations there until April.

Tet Offensive

By 1968, and perhaps in 1967, Johnson's chief adviser on the war, McNamara, had increasingly less faith in the Johnson-Westmoreland model. McNamara quotes GEN William DuPuy, Westmoreland's chief planner, as recognizing that as long as the enemy could fight from the sanctuaries of Cambodia, Laos, and North Vietnam, it was impossible to bring adequate destruction on the enemy, and the model was inherently flawed.[41]

Opposition against him peaked in 1968; see Tet Offensive. On March 31, 1968, Johnson said on national television,

"I shall not seek, and I will not accept, the nomination of my party for another term as your president"

In March, Johnson had also announced a bombing halt, in the interests of starting talks. The first discussions were limited to starting broader talks, as a quid-pro-quo for a bombing halt.:[42]

Vietnamization phase

During the Presidential campaign, a random wire service story headlined that Nixon had a "secret plan for ending the war, but, in reality, Nixon was only considering alternatives at this point. He remembered how Eisenhower had deliberately leaked, to the Communist side in the Korean War, that he might be considering using nuclear weapons to break the deadlock. Nixon adapted this into what he termed the "Madman Strategy".[43]

He told H. R. Haldeman, one of his closest aides,

"I call it the madman theory, Bob.I want the North Vietnamese to believe that I've reached the point that I might do anything to stop the war. We'll just slip the word to them that for God's sake, you know Nixon is obsessed about communism. We can't restrain him when he's angry, and he has his hand on the nuclear button, and Ho Chi Minh himself will be in Paris in two days begging for peace."[44]

Nixon decisionmaking structure

After the election of Richard M. Nixon, a review of U.S. policy in Vietnam was the first item on the national security agenda. Henry Kissinger, the Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs, asked all relevant agencies to respond with their assessment, which they did on March 14, 1969.[45]

"Controlling the policy were a small group of men, President Richard M. Nixon, and which included the President’s Assistant for National Security Affairs, Henry A. Kissinger; the President’s Deputy Assistant for National Security Affairs, Major General Alexander M. Haig; and a few National Security Council officials trusted by Kissinger."[46] Admiral Thomas Moorer, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff; Director of Central Intelligence Richard Helms, and Ambassador Ellsworth Bunker also were involved, but Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird and Secretary of State William Rogers were rarely part of the inner discussions.

Policy toward SVN

U.S. policy changed to one of turning ground combat over to South Vietnam, a process called Vietnamization, a term coined in January 1969. Nixon, in contrast, saw resolution not just in Indochina, in a wider scope. He sought Soviet support, saying that if the Soviet Union helped bring the war to an honorable conclusion, the U.S. would "do something dramatic" to improve U.S.-Soviet relations. [42] In worldwide terms, Vietnamization replaced the earlier containment policy[47] with detente.[48] Also in 1969, both overt and covert Paris Peace Talks began.

While Nixon hesitated to authorize a military request to bomb Cambodian sanctuaries, which civilian analysts considered less important than Laos, he authorized, in March, bombing of Cambodia as a signal to the North Vietnamese. While direct attack against North Vietnam, as was later done in Operation Linebacker I, might be more effective, he authorized the Operation MENU bombing of Cambodia, starting on March 17. These bombings were kept secret from the U.S. leadership and electorate; the North Vietnamese clearly knew they were being bombed. It first leaked to the press in May, and Nixon ordered warrantless surveillance of key staff. [49]

Nixon also directed Cyrus Vance to go to Moscow in March, to encourage the Soviets to put pressure on the North Vietnamese to open negotiations with the U.S. [50] The Soviets, however, either did not want to get in the middle, or had insufficient leverage on the North Vietnamese.

Final air support phase

In the transition to full "Vietnamization," U.S. and third country ground troops turned ground combat responsibility to the Army of the Republic of Vietnam. Air and naval combat, combat support, and combat service support from the U.S. continued. While the ARVN improved in local security and small operations, Operation Lam Son 719, in February 1971, the first large operation with only ARVN ground forces, they took casualties that the South Vietnamese leadership considered unacceptable, and withdrew. This operation still had U.S. helicopters lifting the crews, and U.S. intelligence and artillery support.

They did much better against the 1972 Eastertide invasion, but this still involved extensive U.S. air support. To stop the logistical support of the Eastertide invasion, Nixon launched Operation Linebacker I, with the operational goal of disabling the infrastructure of infiltration. One of the problems of the Republic of Vietnam's Air Force is that it never operated under central control, even for a specific maximum-effort air offensive. South Vietnamese aircraft always were controlled by regional corps commanders, so never developed skills in deep battlefield air interdiction.

When the North refused to return to negotiations in late 1972, Nixon, in mid-December, ordered bombing at an unprecedented level of intensity, Operation Linebacker II. This was at the strategic and grand strategic levels, attacking not so much the infiltration infrastructure, but North Vietnam's ability to import supplies, its internal transportation and logistics, command and control, and integrated air defense system. Within a month of the start of the operation, a peace agreement was signed.

Peace accords were finally signed on 27 January 1973, in Paris. U.S combat troops immediately began withdrawal, and prisoners of war were repatriated. U.S. supplies and limited advise could continue. In theory, North Vietnam would not reinforce its troops in the south. In practice, the North did not remove its large forces from the south, and eventually committed additional large forces in a conventional invasion.

Fall of South Vietnam

While Ford, Nixon's final vice-president, succeeded Nixon, most major policies had been set by the time he took office. He was under a firm Congressional and public mandate to withdraw.

The North, badly damaged by the bombings of 1972, recovered quickly and remained committed to the destruction of its rival. There was little U.S. popular support for new combat involvement, and no Congressional authorizations to expend funds to do so. North Vietnam launched a new conventional invasion in 1975 and seized Saigon on April 30.[51]

No American combat units were present until the final days, when Operation FREQUENT WIND was launched to evacuate Americans and 5600 senior Vietnamese government and military officials, and employees of the U.S. The 9th Marine Amphibious Brigade, under the tactical command of Alfred M. Gray, Jr., would enter Saigon to evacuate the last Americans from the American Embassy to ships of the Seventh Fleet. Ambassador Graham Martin was among the last civilians to leave. [52] In parallel, Operation Eagle Pull evacuated U.S. and friendly personnel from Phnom Penh, Cambodia, on April 12, 1975, under the protection of the 31st Marine Amphibious Unit, part of III MAF.

Vietnam was unified under Communist rule. Lê Duẩn's government purged South Vietnamese who had fought against the North, imprisoning over one million people and setting off a mass exodus and humanitarian disaster.[53][54][55][56][57] Large numbers of South Vietnamese became refugees, many as desperate "boat people."

Under the leadership of Pol Pot, the Khmer Rouge murdered over 2 million Cambodians in the killing fields, out of a population of around 8 million.[13][58] The Pathet Lao slaughtered tens of thousands of Hmong tribesmen.[59][60]

Southeast Asia did not become a monolithic Communist bloc. It took over a decade for the U.S. military to recover from some of its internal turmoil and breakdown in discipline.

References

- ↑ It's worth mentioning that, in addition to banning TV from showing film of combat, the U.S. military also tried to reduce the number of deaths during the Iraq War with improved medical triage. The result was that, though more soldiers survived, many of them returned home with severe disablement, including especially lots of brain injuries which meant they would likely be dependent for life on care by their families.

- ↑ The Pentagon Papers (1971), Beacon Press, vol. 3, p. 134.

- ↑ The Pentagon Papers (1971), Beacon Press, vol. 3, p. 119.

- ↑ The Pentagon Papers (1971), Beacon Press, vol. 3, p. 140.

- ↑ The Pentagon Papers (1971), Beacon Press, vol. 3, p. 140.

- ↑ Charles Hirschman et al., "Vietnamese Casualties During the American War: A New Estimate," Population and Development Review, December 1995.

- ↑ Shenon, Philip. 20 Years After Victory, Vietnamese Communists Ponder How to Celebrate, 23 April 1995. Retrieved on 24 February 2011.

- ↑ Associated Press, 3 April 1995, "Vietnam Says 1.1 Million Died Fighting For North."

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Lewy, Guenter (1978). America in Vietnam. New York: Oxford University Press. Appendix 1, pp.450-453

- ↑ Thayer, Thomas C (1985). War Without Fronts: The American Experience in Vietnam. Boulder: Westview Press. Ch. 12.

- ↑ Wiesner, Louis A. (1988). Victims and Survivors Displaced Persons and Other War Victims in Viet-Nam. New York: Greenwood Press. p.310

- ↑ Thayer, Thomas C (1985). War Without Fronts: The American Experience in Vietnam. Boulder: Westview Press. p.106.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Heuveline, Patrick (2001). "The Demographic Analysis of Mortality in Cambodia." In Forced Migration and Mortality, eds. Holly E. Reed and Charles B. Keely. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

- ↑ Marek Sliwinski, Le Génocide Khmer Rouge: Une Analyse Démographique (L'Harmattan, 1995).

- ↑ Banister, Judith, and Paige Johnson (1993). "After the Nightmare: The Population of Cambodia." In Genocide and Democracy in Cambodia: The Khmer Rouge, the United Nations and the International Community, ed. Ben Kiernan. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Southeast Asia Studies.

- ↑ Warner, Roger, Shooting at the Moon, (1996), pp366, estimates 30,000 Hmong.

- ↑ Obermeyer, "Fifty Years of Violent War Deaths from Vietnam to Bosnia", British Medical Journal, 2008, estimates 60,000 total.

- ↑ T. Lomperis, From People's War to People's Rule, (1996), estimates 35,000 total.

- ↑ Small, Melvin & Joel David Singer, Resort to Arms: International and Civil Wars 1816–1980, (1982), estimates 20,000 total.

- ↑ Taylor, Charles Lewis, The World Handbook of Political and Social Indicators, estimates 20,000 total.

- ↑ Stuart-Fox, Martin, A History of Laos, estimates 200,000 by 1973.

- ↑ An enabling Party resolution was passed in January, but this was the date of starting to build infrastructure; combat use of that infrastructure was still two or more years away. See Vietnamese Communist grand strategy

- ↑ , Chapter 6, "The Advisory Build-Up, 1961-1967," Section 1, pp. 408-457, The Pentagon Papers, Gravel Edition, Volume 2

- ↑ William Colby, Lost Victory, 1989, p. 173, quoted in McMaster, p. 165

- ↑ William M. Leary (Winter 1999-2000), "CIA Air Operations in Laos, 1955-1974, Supporting the "Secret War"", Studies in Intelligence

- ↑ Haas, Michael E. (1997). Apollo’s Warriors: US Air Force Special Operations during the Cold War. Air University Press., p. 165

- ↑ Holman, Victor (1995). Seminole Negro Indians, Macabebes, and Civilian Irregulars: Models for the Future Employment of Indigenous Forces.

- ↑ Haas, pp. 212-214, 221-224

- ↑ Shultz, Richard H., Jr. (2000), the Secret War against Hanoi: the untold story of spies, saboteurs, and covert warriors in North Vietnam, Harper Collins Perennial, p. 18

- ↑ Shultz, p. 176

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 H. R. McMaster (1997), Dereliction of Duty: Lyndon Johnson, Robert McNamara, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Lies That Led to Vietnam, Harpercollins, pp. 120-134

- ↑ Kennan, George F. (1967), Memoirs 1925-1950, Little, Brown, pp. 53-54

- ↑ Halberstam, David (1972), The Best and the Brightest, Random House, pp. 121-122

- ↑ Thomas, Evan (October 2000), "Bobby: Good, Bad, And In Between - Robert F. Kennedy", Washington Monthly

- ↑ , Chapter 1, "U.S. Programs in South Vietnam, Nov. 1963-Apr. 1965," Section 1, pp. 1-56, The Pentagon Papers, Gravel Edition, Volume 3

- ↑ McMaster, pp. 59-60

- ↑ Lyndon B. Johnson (November 26, 1963), National Security Action Memorandum 273: South Vietnam

- ↑ Joint Chiefs of Staff (13 February 2008), Department of Defense Joint Publication 5-0: Joint Operation Planning

- ↑ Carlson, Justin, "The Failure of Coercive Diplomacy: Strategy Assessment for the 21st Century", Hemispheres: Tufts Journal of International Affairs

- ↑ Morgan, Patrick M. (2003), Deterrence Now, Cambridge University Press

- ↑ Gen. William E Dupuy, August 1, 1988 interview, quoted by McNamara, pages 212 and 371.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Henry Kissinger (1973), Ending the Vietnam War: A history of America's Involvement in and Extrication from the Vietnam War, Simon & Schuster, p. 50

- ↑ Karnow, p. 582

- ↑ Carroll, James (June 14, 2005), "Nixon's madman strategy", Boston Globe

- ↑ Kissinger, p. 50

- ↑ Foreign Relations of the United States, 1969–1976, vol. Volume VIII, Vietnam, Office of the Historian, U.S. Department of State, January–October 1972

- ↑ Kissinger, pp. 27-28

- ↑ Kissinger, pp. 249-250

- ↑ Karnow, p. 591-592

- ↑ Kissinger, pp. 75-78

- ↑ Military History Institute of Vietnam, Victory in Vietnam: The Official History of the People's Army of Vietnam, 1954-1975 (2002), Hanoi's official historyexcerpt and text search

- ↑ Shulimson, Jack, The Marine War: III MAF in Vietnam, 1965-1971, 1996 Vietnam Symposium: "After the Cold War: Reassessing Vietnam" 18-20 April 1996, Vietnam Center and Archive at Texas Tech University

- ↑ Desbarats, Jacqueline. "Repression in the Socialist Republic of Vietnam: Executions and Population Relocation", from The Vietnam Debate (1990) by John Morton Moore. "We know now from a 1985 statement by Nguyen Co Tach that two and a half million, rather than one million, people went through reeducation....in fact, possibly more than 100,000 Vietnamese people were victims of extrajudicial executions in the last ten years....it is likely that, overall, at least one million Vietnamese were the victims of forced population transfers."

- ↑ Anh Do and Hieu Tran Phan, Camp Z30-D: The Survivors, Orange County Register, 29 April 2001.

- ↑ Associated Press, June 23, 1979, San Diego Union, July 20, 1986 reported that 200,000 to 400,000 "boat people" died at sea.

- ↑ Rummel, Rudolph, Statistics of Vietnamese Democide, in his Statistics of Democide, 1997.

- ↑ Nghia M. Vo, The Bamboo Gulag: Political Imprisonment in Communist Vietnam (McFarland, 2004).

- ↑ Sharp, Bruce (1 April 2005). Counting Hell: The Death Toll of the Khmer Rouge Regime in Cambodia. Retrieved on 6 March 2013.

- ↑ Jane Hamilton-Merritt, Tragic Mountains: The Hmong, the Americans, and the Secret Wars for Laos, 1942–1992 (Indiana University Press, 1999), pp337-460.

- ↑ Forced Back and Forgotten (Lawyers’ Committee for Human Rights, 1989), p8.