imported>Paul Wormer |

imported>Paul Wormer |

| (19 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) |

| Line 1: |

Line 1: |

| '''Fritz Haber''' (9 December 1868, [[Breslau]] – 29 January 1934, [[Basel]]) was a German chemist. He was awarded the [[Nobel Prize in Chemistry]] in 1918 for the synthesis of [[ammonia]] from the gaseous [[chemical element|elements]] [[hydrogen]] and [[nitrogen]]. [[Ammonia]] is an important feedstock for artificial fertilizers and explosives. In [[World War I]] Haber supported the use of chemical weapons and actively worked on their development. Of Jewish origin, he was forced to resign his position as director of the [[Kaiser Wilhelm Institut]] in 1933, whereupon he left Germany. He died of a heart attack on a visit to Switzerland.

| | ==Parabolic mirror== |

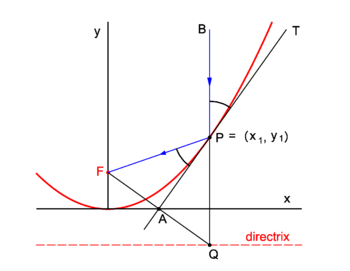

| == Life == | | {{Image|Refl parab.png|right|350px|Fig. 2. Reflection in a parabolic mirror}} |

| ===Youth and education===

| | Parabolic mirrors concentrate incoming vertical light beams in their focus. We show this. |

| Fritz Haber was born into an assimilated Jewish family. His father, Siegfried Haber, ran a business of dye pigments, paints, and pharmaceuticals. For quite a number of years he also served as alderman of Breslau (then a German city, now the Polish city of [[Wrocław]]). At Fritz's birth, serious medical complications occurred and his mother, Paula—née Haber, a first cousin of Siegfried—died three weeks later. It seemed that Fritz' father blamed the child for the mother's death. This probably was the reason that father and son never became close later in life and that tensions between them arose often.

| |

|

| |

|

| Haber attended the humanistic gymnasium St. Elizabeth in Breslau, where the curriculum contained German language and literature, Latin, Greek, mathematics and some physics, but hardly any chemistry. Fritz had a keen interest in chemistry, already as a school boy he performed chemical experiments. After finishing the gymnasium (September 29, 1886 at the age of seventeen)

| | Consider in figure 2 the arbitrary vertical light beam (blue, parallel to the ''y''-axis) that enters the parabola and hits it at point ''P'' = (''x''<sub>1</sub>, ''y''<sub>1</sub>). The parabola (red) has focus in point ''F''. The incoming beam is reflected at ''P'' obeying the well-known law: incidence angle is angle of reflection. The angles involved are with the line ''APT'' which is tangent to the parabola at point ''P''. It will be shown that the reflected beam passes through ''F''. |

| he went to the Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität—usually referred to as the [[University of Berlin]]—to study chemistry. (This choice was against his father's wishes, who had preferred a commercial education for his son.) The director of the chemistry department of Berlin University, [[August Wilhelm von Hofmann]] close to seventy at the time, was a poor teacher and had ignored the upkeep of the chemistry lab. As a consequence Fritz Haber found his first semester in Berlin rather disappointing and he decided, as was not unusual for 19th century German students, to switch universities. He chose the [[University of Heidelberg]], where he arrived in the summer semester of 1887 and continued his studies under [[Robert Wilhelm Bunsen]]. He did his second through fourth [[semester]] in Heidelberg. From mid 1889 until mid 1890 Haber spent time in the army.

| |

| {{Image|Fritz Haber age 22.jpeg|right|250px|Fritz Haber at age 22}}

| |

| In the fall of 1890 he went back to Berlin, this time to the ''Technische Hochschule'' of [[Charlottenburg]] (now the [[Technical University Berlin]]). He worked here under [[Carl Liebermann]] who had a cross appointment at Berlin University. Charlottenburg did not have the the right to grant doctorates (it received it later, in 1899). Having done his thesis work at Charlottenburg, Haber received formally his doctorate in organic chemistry at the University of Berlin (May 29, 1891) on basis of a thesis entitled ''Über einige Derivate des Piperonal'' (About some derivatives of [[Piperonal]]).

| |

|

| |

|

| After completion of his university studies, Fritz's father, who had not given up his hope that his son would become a business man, insisted that he do a few apprenticeships in chemical industry. Although Fritz Haber acquired a taste for chemical engineering during these apprenticeships, they also bored him and he convinced his father that he should return to academia to advance his technical knowledge. His father agreed that he spend a semester with [[Georg Lunge]], professor of chemical technology and a distant relative of the Habers, at the [[Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule Zürich|Institute of Technology]] in [[Zurich]]. After that he worked for six months in his father's business, which finally made Haber senior realize that his son's talent was not in commerce.

| | Clearly ∠''BPT'' = ∠''QPA'' (they are vertically opposite angles). Further ∠''APQ'' = ∠''FPA'' because the triangles ''FPA'' and ''QPA'' are congruent and hence ∠''FPA'' = ∠''BPT''. |

|

| |

|

| So finally his father agreed that he take up a scientific career and Fritz went to work with [[Ludwig Knorr]] at the [[University of Jena]], publishing with him one paper.<ref>Ludwig Knorr and Fritz Haber, ''Ueber die Konstitution des Diacetbernsteinsäureesters'' (On the constitution of diaceto amber acid ester), Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft

| | We prove the congruence of the triangles: By the definition of the parabola the line segments ''FP'' and ''QP'' are of equal length, because the length of the latter segment is the distance of ''P'' to the directrix and the length of ''FP'' is the distance of ''P'' to the focus. The point ''F'' has the coordinates (0,''f'') and the point ''Q'' has the coordinates (''x''<sub>1</sub>, −''f''). The line segment ''FQ'' has the equation |

| Vol. '''27''', pp. 1151 – 1167</ref> . In Jena in 1893, Haber converted to the [[Protestantism|Protestant]]-Christian faith, against his father's wishes.

| | :<math> |

| ===Karslruhe===

| | \lambda\begin{pmatrix}0\\ f\end{pmatrix} + (1-\lambda)\begin{pmatrix}x_1\\ -f\end{pmatrix}, \quad 0\le\lambda\le 1. |

| After one and a half year in Jena, still uncertain whether to devote himself to chemical engineering or physical chemistry, Haber traveled in the spring of 1894 to the [[Technical University of Karlsruhe]], without being certain of a position there. After having worked for several months at the university as an unpaid assistant, the professor of Chemical Technology, [[Hans Bunte]], put him on the payroll (on December 16, 1894). Two years later Haber made his ''Habilitation'' with a dissertation entitled ''Experimentelle Untersuchungen über Zersetzung und Verbrennung von Kohlenwasserstoffen'' (Experimental Studies on the Decomposition and Combustion of Hydrocarbons) (1896) and Haber received the title ''Privat-Dozent''. Bunte was especially interested in combustion chemistry and [[Carl Engler]], who was also in Karlsruhe, introduced Haber to the study of petroleum. Haber's subsequent work was greatly influenced by Bunte and Engler and he always spoke of them with great respect. In 1898, Haber published the textbook ''Grundriss der Technischen Elektrochemie auf theoretischer Gundlage'' (Outline of technical electrochemistry on theoretical basis) and obtained the honorary title of ''außerordentlicher'' (extraordinary) Professor in technical electrochemistry (December 6, 1898) that gave him tenure.

| | </math> |

| | | The midpoint ''A'' of ''FQ'' has coordinates (λ = ½): |

| In 1901, Haber married Clara Immerwahr, daughter of a respected Jewish family in Breslau, whom he had known as a teenager. Clara, who also had converted to the protestant religion, matched Fritz in ambition and determination, having fought against prejudice and opposition to become the first woman to obtain a doctorate in science at Breslau University. She committed suicide the night of May 1, 1915, shooting herself with Fritz’s army pistol, supposedly after heated arguments over Fritz’s involvement with the poison gas campaign on the western front during WWI.

| | :<math> |

| | | \frac{1}{2}\begin{pmatrix}0\\ f\end{pmatrix} + \frac{1}{2}\begin{pmatrix}x_1\\ -f\end{pmatrix} = |

| From 1904 on Haber worked on the catalytic formation of ammonia. In 1905 he published his book ''Thermodynamik technischer Gasreaktionen'' (Thermodynamics of technical gas reactions), which treats the foundations of his subsequent thermochemical work. In 1906 he succeeded [[Max Julius Le Blanc]] to the Karlsruhe chair of physical chemistry and electrochemistry. Le Blanc had left because he was appointed to the prestigious chair in Leipzig vacated by [[Wilhelm Ostwald]].

| | \begin{pmatrix}\frac{1}{2} x_1\\ 0\end{pmatrix}. |

| {{Image|Friz Haber group 1909.jpg|left|450px|<small>Research group of Fritz Haber in Karlsruhe (1909). Fritz Haber sits in the middle (5th from the left) just above man sitting on the ground; seated, 2nd from the left, R. Le Rossignol.</small>}}

| | </math> |

| Haber remained in Karlsruhe until 1911 and gained a great reputation, especially in electrochemistry and chemical thermodynamics. He assembled a very large research group, of about forty persons (including research students), see the adjacent photograph.

| | Hence ''A'' lies on the ''x''-axis. |

| ====Ammonia synthesis====

| | The parabola has equation, |

| Haber's most important work during his latter years in Karlsruhe concerned the fixation of nitrogen. This work was mainly motivated by the needs of agriculture. It was known from the work of [[Justus von Liebig]] (1803–1873) that plants need nitrogen, but also that very few plants are able to grow on nitrogen from the air (through bacteria on their roots). Chili [[saltpetre]] (potassium and sodium nitrate) was the most important nitrogen-containing fertilizer at the end of the 19th century, but it was feared that the source would be exhausted somewhere early in the 20th century. Before Haber's work, ammonia was produced from coal and distributed as ammonium sulphate. Obviously an unlimited supply of nitrogen is present in the air (78% of the air is nitrogen), but the question was how to convert it to a form usable by plants. The reaction N<sub>2</sub> + H<sub>2</sub> → 2NH<sub>3</sub> is a good candidate for nitrogen (N<sub>2</sub>) fixation, because the resulting ammonia (NH<sub>3</sub>) can easily be converted into nitrate. The reaction is exothermic (releases heat), and therefore, is not energetically demanding. The problem is reaction speed, high [[pressure]] and a good [[catalyst]] are required to produce ammonia in finite amounts of times. Haber and his coworker, the young Briton Robert Le Rossignol, hit upon the idea of searching among [[transition metal]]s, because [[chromium]], [[manganese]], [[iron]] and [[nickel]] possess very definite catalytic properties. After a few years of hard work the two managed to synthesize ammonia in a way suitable for industrial upscaling. Despite their initial skepticism, in July 1909 representatives of [[BASF]] (Badische Anilin and Soda Fabrik) were finally convinced and enthusiastically began the search for the ideal catalyst and the construction of a synthetic ammonia factory which came on-stream in 1912. The industrial scale-up was largely directed by [[Carl Bosch]], a chemical engineer employed by BASF. The industrial synthesis is known as the [[Haber-Bosch process]]. Just before the outbreak of WWI, BASF was able to produce 30 ton ammonia daily, which turned out to be an important factor in prolonging the war, because the chemical route from ammonia to high explosives is a short one.

| | :<math> |

| ==Berlin==

| | y = \frac{1}{4f} x^2. |

| On October 1, 1911 Haber became director of the newly founded ''Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institut für physikalische Chemie und Elektrochemie'' ([[[[Kaiser Wilhelm Institute|KWI]]) in Dahlem-Berlin.<ref>Since 1953 the institute is called the ''Fritz-Haber-Institut der Max-Planck-Gesellschaft''</ref> With the function came a cross-appointment as honorary full professor at the university of Berlin. For Haber the appointment meant the end as scientist and the beginning as science manager. For quite some time he was busy, not only with building and equipping the new laboratory, but also with the rules and regulations that would govern the new organization. At the festive opening of the institute German Emperor Wilhelm II had expressed the wish that the new institute develop a hydrogen/methane/air sensor for use in coal mines. Haber set his section leader Richard Leider to work and together they came up with a kind of organ pipe (a ''Schlagwetterpfeife'', a "methane whistle") that gave an audible tone different for pure air than for an air-other-gas mixtures. In agreement with the aim of the new institute, it was left to industry to manufacture and sell the new invention.<ref>Although the device worked, it was replaced soon by electric sensors of thermal conductivities of gas mixtures.</ref>

| | </math> |

| | | The equation of the tangent at ''P'' is |

| When World War I started in the fall of 1914, Fritz Haber undersigned gladly the extremely chauvinistic [[Aufruf an die Kulturwelt]]. As a chauvinist patriot he was happy that he was soon called upon to make his and his institute's talents available to the war effort. He assembled a large team, consisting eventually of more than 150 scientists and 1300 technical personnel. Their task was to develop the tools of gas warfare and, at the same time, to design countermeasures such as efficient gas masks.

| | :<math> |

| | | y = y_1 + \frac{x_1}{2f} (x-x_1)\quad \hbox{with}\quad y_1 = \frac{x_1^2}{4f}. |

| <!--

| | </math> |

| Ferdinand Flury, later to become a leader in industrial hygiene and toxicology at the University of Wuerzburg, directed department "E." Together with a staff of 10 scientists and 15 assistants, he was responsible for studies on the toxicity of war gases, animal experiments, and industrial hygiene. The group conducted experiments with rats, mice, guinea pigs, dogs, monkeys, and even horses. The acute inhalation toxicity of numerous agents, thought to be useful in gas warfare, was thoroughly explored. The work on the mechanisms of toxicity of gases used in warfare led to the development of effective methods of treatment and countermeasures against gas toxicity. Fritz Haber himself was not only active in directing research, but traveled repeatedly to the western and eastern front where, often under enemy fire, he personally supervised the deployment of the equipment necessary to conduct gas warfare. He was tireless and highly motivated by his patriotism. It was those activities that, in the eyes of Germany's enemies, made him a war criminal. For some time after the war, he was afraid that charges would be pressed against him.

| | This line intersects the ''x''-axis at ''y'' = 0, |

| Next is the Fritz Haber Center for Molecular Dynamics of the [[Hebrew University of Jerusalem | Hebrew University of Jerusalem]] named after

| | :<math> |

| him. Because of its role as a military researcher and consultant, he was

| | 0 = \frac{x_1^2}{4f} - \frac{x_1^2}{2f} + \frac{x_1}{2f} x |

| assigned, previously deputy sergeant, the rank of [[Captain (officer)| captain]] granted. His experiments with [[phosgene]] and [[chlorine]] (a byproduct of the color production of the chemical industry), which - against the wishes of his first wife, [[Clara Immerwahr]] (Marriage

| | \Longrightarrow \frac{x_1}{2f} x = \frac{x_1^2}{4f} \longrightarrow x = \tfrac{1}{2}x_1. |

| 1901), who held a PhD in chemistry - was started a few weeks after the war began, made him the father of [[poison gas] weapons], which were used in the [[First World War | World War I]] from Germany. A few days after the first German use of poison gas on 22 April 1915 at

| | </math> |

| [[Ypres]] committed suicide with his wife of Haber's service weapon. After the First World War he was due to the violation of the [[Hague Regulations]] from the [[Allied]] looking at times as a

| | The intersection of the tangent with the ''x''-axis is the point ''A'' = (½''x''<sub>1</sub>, 0) that lies on the midpoint of ''FQ''. The corresponding sides of the triangles ''FPA'' and ''QPA'' are of equal length and hence the triangles are congruent. |

| [[war crimes]] and fled temporarily to the [[Switzerland]]. In his memoirs [[Otto Hahn reported]] on a conversation with Haber: "When I objected that this kind of warfare is contrary to the Hague Convention, he said that the French would have - albeit in poor shape, namely, gas-gun ammunition -- the beginning of this done. Too many lives are saved if the war could be completed more quickly in this way",<ref> Otto Hahn:''My Life.''Munich 1968. </ref>. From 1919, he tried vainly for six years to win from the sea [[gold]] in order to pay the [[German reparations]] too.

| |

| In April 1917 Haber had taken over the management of a ''technical committee'' pesticide, which was to deal with the disinfestation of accommodation (bed bugs and lice) and silos

| |

| (moth). This was done with [[hydrogen cyanide]] gas, which was

| |

| produced in the so-called''procedural''tun, was by [[sodium cyanide]] and [[potassium cyanide]] placed in an open wooden vat of dilute [[sulfuric acid]]. <ref> Jürgen Kalthoff:''The dealers of Zyklon B.''Hamburg 1998, ISBN 3-87975-713-5, p. 17-19. </ ref> In March 1919,

| |

| the [[German Society for Pest Control]] Founded (Degesch), whose first

| |

| line Haber, held in 1920 [[Walter Heerdt]].

| |

| | |

| Wife: Clara Immerwahr (chemist, b. 21-Jun-1870, m. 1901, d. 2-May-1915, suicide)

| |

| Son: Hermann Haber (b. 1902, d. 1946, suicide)

| |

| Wife: Charlotte Nathan (m. 25-Aug-1917, div. 1927)

| |

| Daughter: Eva-Charlotte (b. 1918)

| |

| Son: Ludwig-Fritz (b. 1921)

| |

| | |

| High School: St. Elizabeth Classical School, Breslau, Prussia

| |

| University: University of Heidelberg (attended)

| |

| University: PhD Chemistry, University of Berlin (1891)

| |

| Scholar: Chemistry, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology

| |

| Scholar: Chemistry, University of Jena (1893-94)

| |

| Teacher: Chemical Technology, University of Karlsruhe (1894-96)

| |

| Lecturer: Chemical Technology, University of Karlsruhe (1896-1906)

| |

| Professor: Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry, University of Karlsruhe (1906-11)

| |

| Professor: Kaiser Wilhelm Institute, Berlin-Dahlem (1911-33)

| |

| Professor: Chemistry, University of Berlin (1911-33)

| |

| | |

| [[Ferdinand Flury]], which was like Heerdt, and [[Bruno Tesch (chemist) | Bruno Tesch]] Haber's

| |

| former employee, developed a cyclone in 1920 and received patents for it. Cyclone A consisted of cyanide gas and the accompanying strong-smelling warning agent

| |

| [[bromoacetic acid]] <nowiki /> methyl ester,

| |

| which was delivered in bottles with a pressure

| |

| atomizer nozzle. A cyclone but could not

| |

| displace the vat method, and was considered

| |

| uneconomic. <ref> Jürgen Kalthoff:''The dealers

| |

| ...''. Hamburg 1998, ISBN

| |

| 3-87975-713-5, p. 28-30. </ ref> The decisive

| |

| progress towards a safe method bound with cyanide

| |

| in the warning agent to a porous carrier material

| |

| is not under pressure and after opening the tin

| |

| slowly releases gases, succeeded Walter Heerdt, of

| |

| this procedure on 20 June 1922 for

| |

| a patent for [[Zyklon B]] ((<ref> filed for patent

| |

| | country = U.S. | V-No = 438,818 | title =

| |

| procedures for pest control | A-Date = 1922-06-20

| |

| | date = 1926 V -12-27 | inventor = Walter Heerdt

| |

| | Applicant Degesch =)) </ ref>. This procedure was used

| |

| for fumigation with [[Zyklon B]]. <ref> Jürgen

| |

| Kalthoff:''The dealers ...'' Hamburg 1998, ISBN

| |

| 3-87975-713-5, p. 234 (often suggested a direct

| |

| connection Haber with Zyklon B is not given). </ref> Fritz Haber had since the founding of the

| |

| [[IG Farben]] 1925] in their [[Board].

| |

| | |

| After the [[Nazi]] 1933 at the Kaiser Wilhelm institutes the [[Aryan paragraph]]

| |

| s penetrated and dismissed the Jewish people, which even he could not prevent Haber in May 1933

| |

| could be put into retirement. He emigrated in the late fall of 1933 after the

| |

| [[Cambridge]], where he had not yet received a professorship at the [[University of Cambridge|University]] and died shortly after 1934 on his

| |

| way through [[Basel]].

| |

| | |

| | |

| == Impact == | |

| The research results show the

| |

| Haber [[Janus | Janus-faced]] of his scientific

| |

| work: On one hand, through the development of

| |

| ammonia synthesis (to manufacture explosive) or a

| |

| technical process for the production and use of

| |

| poison gas warfare, as it has become possible on

| |

| an industrial basis. Nor would it be without these

| |

| skills, the diet of mankind today is not

| |

| possible. The world

| |

| annual production of synthesized nitrogen

| |

| fertilizer is currently more than 100 million

| |

| tons.

| |

| Without this production makes possible the

| |

| Haber-Bosch process accounted for half of the

| |

| current world population, the food base. <ref>

| |

| Joerg Albrecht:''Bread and war from the

| |

| air.''In:''[[# Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung,

| |

| Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung Sunday (FAS) |

| |

| Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung Sunday ]].'' 41,

| |

| 2008, p. 77 (figures from 'Nature Geosience ").</ref>

| |

| | |

| == Literature == | |

| * Joerg Albrecht:''Bread and wars from the air. In the 77th'': [[# Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung (FAS) | Frankfurter Allgemeine

| |

| Zeitung Sunday]] 41/2008, p.

| |

| * [[Adolf Henning fruit]], Joachim Zepelin:''The tragedy of the despised love .''In: Mannheimer Forum''1994/95''. Piper, Munich 1995.

| |

| * Adolf Henning Frucht:''Fritz Haber and pest control during the 1st World War II and during the inflation''. In:''Dahlem Archive discussions''. Volume 11, 2005, p. 141-158.

| |

| * ((NDB | 7 | 386 | 389 | Haber, Fritz Jacob | Erna and Johannes Jaenicke))

| |

| * Fritz Richard Stern:''Five Germany and a life: memories''. Beck, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-406-55811-5.

| |

| * Dietrich Stoltzenberg:''Fritz Haber: Chemist, Nobel Laureate, German, Jew''. Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 1998, ISBN 3-527-29573-9.

| |

| * Margit Szollosi-Janze:''Fritz Haber. 1868-1934. A Biography''. Beck, Munich 1998, ISBN -406-43548-3. Commonscat

| |

| | |

| [http://books.google.nl/books?id=0ekNIaJX3-YC&pg=PP2&cd=1#v=onepage&q=Fritz%20Haber%3A%20Chemist%2C%20Nobel%20Laureate%2C%20German%2C%20Jew%3A%20A%20Biography&f=false]

| |

| | |

| [http://books.google.nl/books?id=EhvSPBWlk3MC&pg=PA860&lpg=PA860&dq=Experimentelle+Untersuchungen+%C3%BCber+Zersetzung+und+Verbrennung+von+Kohlenwasserstoffen&source=bl&ots=6AwteHsH8E&sig=cCHYhIy-XoRojwH-VmjI0x7Puoo&hl=nl&ei=Cc2LS7KnG4_K-QaOsuHjDQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CAYQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=Experimentelle%20Untersuchungen%20%C3%BCber%20Zersetzung%20und%20Verbrennung%20von%20Kohlenwasserstoffen&f=false]

| |

| -->

| |