Irish Free State: Difference between revisions

imported>Aleksander Stos m (typo) |

John Leach (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| (5 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{subpages}} | {{subpages}} | ||

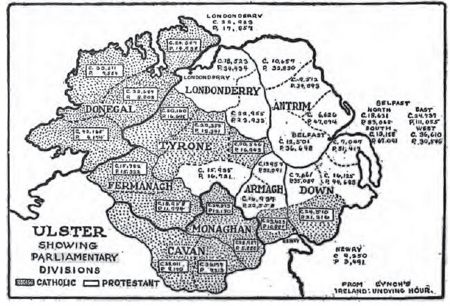

The '''Irish Free State''', now known as [[Ireland (state)|Ireland]], was a dominion of the [[British Empire]] 1922-1948, which was formed after the ratification of the [[Anglo-Irish Treaty]] following the [[Irish War of | The '''Irish Free State''', now known as [[Ireland (state)|Ireland]], was a dominion of the [[British Empire]] 1922-1948, which was formed after the ratification of the [[Anglo-Irish Treaty]] following the [[Irish War of Independence]]. It came into being on December 26, 1922 replacing the Southern Irish State creating after the [[Government of Ireland Act, 1920]], which had split six northern counties in Ulster into a separate entity with a devolved government in [[Belfast]] but remaining in the United Kingdom. Opposition to the Irish Free State was rife, with many ardent [[Republicanism#Ireland|Republicans]] rejecting it. However, the majority, led by [[Michael Collins]] regarded it as a stepping stone to peace and greater freedom. Collins had grown weary of war as he had been the head of the rebel forces throughout the conflict. The country ratified a new constitution under [[Éamon de Valera]] on 29 December, 1937. A full declaration of an independent republic came with the ending of all ties with the [[Commonwealth]] on 21 December 1948. | ||

==Civil War== | ==Civil War== | ||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

[[Image:Ulster1921.jpg|thumb|450px]] | [[Image:Ulster1921.jpg|thumb|450px]] | ||

The birth of the Irish Free State coincided with the [[Irish Civil War]], a conflict between two forces who supported and opposed the [[Anglo-Irish Treaty]]. Two factions emerged in Irish society, with the pro treaty forces led by the interim Prime Minister and de facto commander of the rebel forces, [[Michael Collins]], and the 'irregulars', the anti treaty forces led by [[Eamon De Valera]]. The first task the Irish Free State faced was to win the Civil War and in doing this they recruited a large military and slowly gained the upper hand in the conflict. 75% of the people voted in the pro treaty government into power (at the time known as the pro treaty [[Sinn Fein]]). Historians have criticised the argument that the nation wanted a Free State government, pointing out that the voters were left with the choice of war with the British Empire or peace. The Irish people were war weary and voted for an end to conflict, not an endorsement of the Irish Free State; de Valera ignored those popular wishes and launched a poorly organized civil war that had little popular support and less military success. [[Michael Collins]], the effective head of the new government, built an army from the pro-treaty remnants of the IRA, plus new recruits; he was funded and supplied by the British government. Collins was assassinated by anti-treaty elements near his home in August, 1922, a move that shocked the country. Even without Collins' leadership the Irish army speedily destroyed the insurgency. | The birth of the Irish Free State coincided with the [[Irish Civil War]], a conflict between two forces who supported and opposed the [[Anglo-Irish Treaty]]. Two factions emerged in Irish society, with the pro treaty forces led by the interim Prime Minister and de facto commander of the rebel forces, [[Michael Collins]], and the 'irregulars', the anti treaty forces led by [[Eamon De Valera]]. The first task the Irish Free State faced was to win the Civil War and in doing this they recruited a large military and slowly gained the upper hand in the conflict. 75% of the people voted in the pro treaty government into power (at the time known as the pro treaty [[Sinn Fein]]). Historians have criticised the argument that the nation wanted a Free State government, pointing out that the voters were left with the choice of war with the British Empire or peace. The Irish people were war weary and voted for an end to conflict, not an endorsement of the Irish Free State; de Valera ignored those popular wishes and launched a poorly organized civil war that had little popular support and less military success. [[Michael Collins]], the effective head of the new government, built an army from the pro-treaty remnants of the IRA, plus new recruits; he was funded and supplied by the British government. Collins was assassinated by anti-treaty elements near his home in August, 1922, a move that shocked the country. Even without Collins' leadership the Irish army speedily destroyed the insurgency, after the Free State declared martial law, made unauthorized possession of firearms a capital offence, and executed four rebel leaders without trial. | ||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

===The Army=== | ===The Army=== | ||

After the [[Irish Civil War|Civil War]] the government went about transferring the army from a wartime to a peacetime force. This involved [[demobilization]] of the forces, which numbered 55,000 soldiers and 3,500 officers by the end of the Civil War. Many soldiers deeply resented this policy at a time of high [[unemployment]]. By early 1924, the army had been slashed to 13,000 soldiers and 2,000 officers. Soldiers who had fought in the Civil war and were ‘pro-treaty’ and who had fought under Collins in the Anglo-Irish war (known as the ‘old IRA’) felt they were undervalued and being dismissed ahead of soldiers who had served in the British forces. They were also upset at the Free State government for not living up to its promises of using the treaty as a ''stepping stone to full independence'' as Collins had promised. Matters came to a head on 6 March 1924, when two army officers and old IRA members, [[Liam Tobin]] and [[Emmet Dalton]] sent an ultimatum to the Cosgrave government. In it they outlined their demands: Removal of the [[Army council]], a stop to demobilization and assurances from the Free State army that progress was being made on a full 32 county republic. The government immediately denounced the ultimatum and ordered the arrest of Tobin and Dalton. General [[Richard Mulcahy]] faced strong opposition from Kevin O’ Higgens (Who had replaced Cosgrave due to illness) because he controlled secret groups such as the [[Irish Republican Brotherhood|IRB]] who were in the army. O’ Higgens and other ministers distrusted | After the [[Irish Civil War|Civil War]] the government went about transferring the army from a wartime to a peacetime force. This involved [[demobilization]] of the forces, which numbered 55,000 soldiers and 3,500 officers by the end of the Civil War. Many soldiers deeply resented this policy at a time of high [[unemployment]]. By early 1924, the army had been slashed to 13,000 soldiers and 2,000 officers. Soldiers who had fought in the Civil war and were ‘pro-treaty’ and who had fought under Collins in the Anglo-Irish war (known as the ‘old IRA’) felt they were undervalued and being dismissed ahead of soldiers who had served in the British forces. They were also upset at the Free State government for not living up to its promises of using the treaty as a ''stepping stone to full independence'' as Collins had promised. Matters came to a head on 6 March 1924, when two army officers and old IRA members, [[Liam Tobin]] and [[Emmet Dalton]] sent an ultimatum to the Cosgrave government. In it they outlined their demands: Removal of the [[Army council]], a stop to demobilization and assurances from the Free State army that progress was being made on a full 32 county republic. The government immediately denounced the ultimatum and ordered the arrest of Tobin and Dalton. General [[Richard Mulcahy]] faced strong opposition from Kevin O’ Higgens (Who had replaced Cosgrave due to illness) because he controlled secret groups such as the [[Irish Republican Brotherhood|IRB]] who were in the army. O’ Higgens and other ministers distrusted Mulcahy's motives. They therefore appointed the Garda commissioner Eoin O’ Duffy as supreme commander of the army over Mulcahy. The cabinet demanded Mulcahy's resignation but he had resigned before their message reached him. The main consequence of the Army mutiny was the strengthening of the elected governments grip over the army. | ||

===Foreign Policy=== | ===Foreign Policy=== | ||

Under the [[Anglo-Irish Treaty]] of 1921, the Irish Free State had [[dominion]] status within the British Empire similar to [[South Africa]], [[Australia]] and [[New Zealand]]. But unlike these nations, Ireland had gotten dominion status as a result of bloody [[revolution]]. The Cumann Na nGaedhal government was anxious to vindicate [[Michael Collins]] view that the treaty was a stepping-stone to achieving full independence and greater freedom. As part of this approach it was anxious to follow an independent foreign policy from the beginning. The Irish Free State insisted on having the treaty registered as an agreement between two states at the [[League of Nations]] in [[Geneva]]. In October 1924 the government had sent a representative to the [[United States]]. This was a further advance towards full autonomy, as before this the British dominions had depended on the British ambassador in other countries. It then soon sent representatives to [[France]] and [[Germany]]. By 1932, the Free State government had established diplomatic links with many nations abroad. | Under the [[Anglo-Irish Treaty]] of 1921, the Irish Free State had [[dominion]] status within the British Empire similar to [[South Africa]], [[Australia]] and [[New Zealand]]. But unlike these nations, Ireland had gotten dominion status as a result of bloody [[revolution]]. The Cumann Na nGaedhal government was anxious to vindicate [[Michael Collins]] view that the treaty was a stepping-stone to achieving full independence and greater freedom. As part of this approach it was anxious to follow an independent foreign policy from the beginning. The Irish Free State insisted on having the treaty registered as an agreement between two states at the [[League of Nations]] in [[Geneva]]. In October 1924 the government had sent a representative to the [[United States of America]]. This was a further advance towards full autonomy, as before this the British dominions had depended on the British ambassador in other countries. It then soon sent representatives to [[France]] and [[Germany]]. By 1932, the Free State government had established diplomatic links with many nations abroad. | ||

===Economic Policy=== | ===Economic Policy=== | ||

| Line 67: | Line 67: | ||

[[Divorce]] was banned in the Irish Free State in 1925 at the behest of the Catholic Bishops. A number of prominent Protestants, including the legendary Noble prizewinner and senator [[William Butler Yeats|WB Yeats]] protested in vain against this new law. | [[Divorce]] was banned in the Irish Free State in 1925 at the behest of the Catholic Bishops. A number of prominent Protestants, including the legendary Noble prizewinner and senator [[William Butler Yeats|WB Yeats]] protested in vain against this new law. | ||

The position of women in society disimproved in the 1920’s. Between 1914 and 1923 many women played prominent roles in the struggle for Irish independence (Such as [[Maud Gonne]] and [[ | The position of women in society disimproved in the 1920’s. Between 1914 and 1923 many women played prominent roles in the struggle for Irish independence (Such as [[Maud Gonne]] and [[Constance Markiewicz]]) | ||

One of the more controversial aspects of official policy in Ireland from the 1920’s onwards was the existence of [[censorship]]. In an effort to protect the morals of its citizens, the state appointed censors to check books and films, with the power to edit them or ban them outright. While the Catholic Church supported this, writers and other artists passionately criticized it. Many famous books by Irish and foreign authors were banned, and many writers emigrated as a result. More than any other facet of life, the strict censorship laws epitomized the conservative, inward-looking and insecure nature of Irish society at the time. | One of the more controversial aspects of official policy in Ireland from the 1920’s onwards was the existence of [[censorship]]. In an effort to protect the morals of its citizens, the state appointed censors to check books and films, with the power to edit them or ban them outright. While the Catholic Church supported this, writers and other artists passionately criticized it. Many famous books by Irish and foreign authors were banned, and many writers emigrated as a result. More than any other facet of life, the strict censorship laws epitomized the conservative, inward-looking and insecure nature of Irish society at the time. | ||

Revision as of 03:30, 6 March 2024

The Irish Free State, now known as Ireland, was a dominion of the British Empire 1922-1948, which was formed after the ratification of the Anglo-Irish Treaty following the Irish War of Independence. It came into being on December 26, 1922 replacing the Southern Irish State creating after the Government of Ireland Act, 1920, which had split six northern counties in Ulster into a separate entity with a devolved government in Belfast but remaining in the United Kingdom. Opposition to the Irish Free State was rife, with many ardent Republicans rejecting it. However, the majority, led by Michael Collins regarded it as a stepping stone to peace and greater freedom. Collins had grown weary of war as he had been the head of the rebel forces throughout the conflict. The country ratified a new constitution under Éamon de Valera on 29 December, 1937. A full declaration of an independent republic came with the ending of all ties with the Commonwealth on 21 December 1948.

Civil War

The birth of the Irish Free State coincided with the Irish Civil War, a conflict between two forces who supported and opposed the Anglo-Irish Treaty. Two factions emerged in Irish society, with the pro treaty forces led by the interim Prime Minister and de facto commander of the rebel forces, Michael Collins, and the 'irregulars', the anti treaty forces led by Eamon De Valera. The first task the Irish Free State faced was to win the Civil War and in doing this they recruited a large military and slowly gained the upper hand in the conflict. 75% of the people voted in the pro treaty government into power (at the time known as the pro treaty Sinn Fein). Historians have criticised the argument that the nation wanted a Free State government, pointing out that the voters were left with the choice of war with the British Empire or peace. The Irish people were war weary and voted for an end to conflict, not an endorsement of the Irish Free State; de Valera ignored those popular wishes and launched a poorly organized civil war that had little popular support and less military success. Michael Collins, the effective head of the new government, built an army from the pro-treaty remnants of the IRA, plus new recruits; he was funded and supplied by the British government. Collins was assassinated by anti-treaty elements near his home in August, 1922, a move that shocked the country. Even without Collins' leadership the Irish army speedily destroyed the insurgency, after the Free State declared martial law, made unauthorized possession of firearms a capital offence, and executed four rebel leaders without trial.

Free State government from 1922-1932

Law and Order

The new Cumann Na nGaedhal government faced huge problems in restoring order and stability throughout the state. The war had ended but this had not ended random acts of violence, as many of the anti-treaty republicans refused to recognize the authority of the Dail. Kevin O’ Higgins was Minister responsible for Law and Order and was second in command to the Prime Minister, Cosgrave and Minister for Justice. He tackled the situation in three ways: Foundation of the Garda Siochana, Reform of the court system and public safety acts.

In September 1922 the Garda Siochana replaced the Free State army as the State’s policing force. Their first commissioner was Michael Staines, but he was soon replaced by Eoin O’ Duffy, who remained commissioner until 1933. They were drawn from the ranks of the pro-treaty IRA and they soon established a high level of public support for the force. In 1924 Kevin O’ Higgens introduced the Courts of Justice Act, which reformed the legal system. Both the British and old Sinn Fein courts were abolished and a new court system was established based on District courts, circuit courts, high courts and a supreme court. Minor matters were dealt with by paid judges in the district court that replaced unpaid magistrates. The Circuit court dealt with more serious civil and criminal matters. The two major courts were the high courts that dealt with serious cases and appeals from the lower courts. The Irish legal system was modeled closely on the British one.

The Army

After the Civil War the government went about transferring the army from a wartime to a peacetime force. This involved demobilization of the forces, which numbered 55,000 soldiers and 3,500 officers by the end of the Civil War. Many soldiers deeply resented this policy at a time of high unemployment. By early 1924, the army had been slashed to 13,000 soldiers and 2,000 officers. Soldiers who had fought in the Civil war and were ‘pro-treaty’ and who had fought under Collins in the Anglo-Irish war (known as the ‘old IRA’) felt they were undervalued and being dismissed ahead of soldiers who had served in the British forces. They were also upset at the Free State government for not living up to its promises of using the treaty as a stepping stone to full independence as Collins had promised. Matters came to a head on 6 March 1924, when two army officers and old IRA members, Liam Tobin and Emmet Dalton sent an ultimatum to the Cosgrave government. In it they outlined their demands: Removal of the Army council, a stop to demobilization and assurances from the Free State army that progress was being made on a full 32 county republic. The government immediately denounced the ultimatum and ordered the arrest of Tobin and Dalton. General Richard Mulcahy faced strong opposition from Kevin O’ Higgens (Who had replaced Cosgrave due to illness) because he controlled secret groups such as the IRB who were in the army. O’ Higgens and other ministers distrusted Mulcahy's motives. They therefore appointed the Garda commissioner Eoin O’ Duffy as supreme commander of the army over Mulcahy. The cabinet demanded Mulcahy's resignation but he had resigned before their message reached him. The main consequence of the Army mutiny was the strengthening of the elected governments grip over the army.

Foreign Policy

Under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921, the Irish Free State had dominion status within the British Empire similar to South Africa, Australia and New Zealand. But unlike these nations, Ireland had gotten dominion status as a result of bloody revolution. The Cumann Na nGaedhal government was anxious to vindicate Michael Collins view that the treaty was a stepping-stone to achieving full independence and greater freedom. As part of this approach it was anxious to follow an independent foreign policy from the beginning. The Irish Free State insisted on having the treaty registered as an agreement between two states at the League of Nations in Geneva. In October 1924 the government had sent a representative to the United States of America. This was a further advance towards full autonomy, as before this the British dominions had depended on the British ambassador in other countries. It then soon sent representatives to France and Germany. By 1932, the Free State government had established diplomatic links with many nations abroad.

Economic Policy

The Anglo-Irish treaty granted the Free State full fiscal autonomy. However in practice the new state was heavily dependant on the British market, which remained the main consumer of Irish exports. In addition the banking systems of both countries were closely connected. The partition of Ireland in 1920 resulted in the loss of the most industrialized part of the country. Furthermore, the War of Independence and the Civil War had serious implications for the new State, with widespread destruction of property and transport. The demands to restore law and order by the people put a great strain on the economy. From the outset the Cumann Na nGaedhal government adapted a conservative economic policy. Under the direction of Ernest Blythe, the Minister for Finance from 1923, this policy was characterized by a desire to keep taxation and government expenditure low. The department of finance restricted strict control over the expenditure of other government departments. Balancing the budget became the foremost concern.

Although the Cumann Na nGaedhal government was the heir of Arthur Griffiths Sinn Fein party, it did not practice his protectionist policies. In contrast they implemented a policy of free trade, which involved minimal protection of industry by government. This suited larger farming families and big brewing and distilling industries that exported to England. Agriculture, rather than Industry remained the key concern of the Cosgrave government.

Agriculture

During the 1920’s agriculture was the greatest employer of Irish people and accounted for 80% of Irish exports. The Minister for agriculture, Patrick Hogan, took a number of initiatives to advance agriculture in Ireland: (1) He introduced grading and inspection for butter, meat and eggs in order to improve exports. (2) Land purchase was completed by the Land Commission, which replaced the congested districts boards in 1923, (3) Greater emphasis was placed on agricultural instruction, with an improved system of advisers and evening classes, (4) In order to encourage farmers to borrow investment for their land, the Agricultural Credit Corporation (The ACC) was set up in 1927.

The agricultural policies of the Cumann Na nGaedhal government greatly favoured the larger farming families, who in turn were the greatest supporters of the government. The majority of Irish farmers though farmed on small uneconomic holdings. Both they and landless labourers gained little from government policies, and emigration continued strong through the 1920’s. Although agriculture accounted for half the jobs in the Irish economy in the 1920’s, it contributed to only a third of National Income.

Industrial Development

There was a lack of capital investment, an absence of raw materials such as coal and iron and intense competition from British goods in the Free State in the 1920’s and all of this impeded any sort of industrial progression. Larger industries were represented by thriving export orientated firms such as Guinness or Jacobs. They strongly favoured a policy of free trade with minimal government interference or protection. However in response to complaints from smaller industries, the Minister for Finance Ernest Blythe placed tariffs on imported goods such as shoes, soap, candles and motor bodies in order to encourage small industries to develop.

The most dramatic economic achievement was the establishment of a hydroelectric dam in Ardnacrusha; Shannon in 1929.The contract was given to a German firm and was worth five million pounds. During the construction period of 1925-1929 the project provided employment to 4,000 Irish construction workers. Despite some opposition, the Shannon Scheme was an outstanding success and was seen as one of the greatest achievements of the Cumann Na nGaedhal government. The government had set up a semi-state company in 1927 (The ESB) to oversee the production and distribution of electricity and this company totally transformed the living and working conditions in the countryside in years ahead.

While the ESB and the Ardnacrusha dam were successful, Industrial production on a whole was slow in the 1920’s. Between 1925 and 1939, the numbers employed in Industry grew by 5,000.

Social Policy

The same principles of limited government intervention in the economy and balanced budgets applied to social policy as well. In an effort to balance the budget, old-age pensions were reduced by a shilling a week in 1924. Unemployment assistance was only applicable to a small percentage of workers, who only received payments for the first six months after losing their jobs. After this they had to depend on a means tested home assistance allowance, which was difficult to obtain. As a result emigration remained the only reliable option for many people.

Public healthcare had not developed much since the 19th century. Poorer people who were old or sick were frequently cared for in county homes, which were old workhouses. Were it not for the involvement of religious organizations of priests, nuns and monks in healthcare and education, the condition of the poor would have been much worse.

Education

In 1926 the school attendance act introduced compulsory school attendance for children between the ages of six and fourteen. During the 1920’s about 90% of children did not attend school beyond primary school. At secondary level, some changes were made. The old intermediate examinations were abolished and replaced by intermediate Junior and Leaving certificate examinations. Payments by results were abolished, and schools were given grants by the department of education instead.

Technical schools had been set up in 1899, but they were underfunded and poorly attended. In 1930 therefore, the government introduced the Vocational education act to reform technical schools. This established 38 vocational educational committees (VECs) to organize and oversee the provision of vocational education. Because vocational schools did not prepare children for leaving and junior certificates, many parents considered them inferior to secondary schools.

Irish was considered very important in the new education system. In 1922 all primary schools were instructed to teach Irish for at least one hour a day. From 1926 onwards all infant classes were to be taught through the medium of Irish. Special summer schools in Irish were to be organized to improve teacher’s curriculum. Schools, which taught all subjects exclusively through Irish, were given grants. Irish was also made compulsory for entering the civil service.

Culture

The Irish Free State was culturally conservative and inward looking in contrast with the revolutionary struggle that brought it about. As a result of partition, the southern state was overwhelmingly catholic in composition and the catholic church exercised great influence in guiding peoples lives. As a recently independent country the Irish Free State was determined to establish its own cultural identity and was sensitive to any criticism from both home and abroad.

Divorce was banned in the Irish Free State in 1925 at the behest of the Catholic Bishops. A number of prominent Protestants, including the legendary Noble prizewinner and senator WB Yeats protested in vain against this new law.

The position of women in society disimproved in the 1920’s. Between 1914 and 1923 many women played prominent roles in the struggle for Irish independence (Such as Maud Gonne and Constance Markiewicz)

One of the more controversial aspects of official policy in Ireland from the 1920’s onwards was the existence of censorship. In an effort to protect the morals of its citizens, the state appointed censors to check books and films, with the power to edit them or ban them outright. While the Catholic Church supported this, writers and other artists passionately criticized it. Many famous books by Irish and foreign authors were banned, and many writers emigrated as a result. More than any other facet of life, the strict censorship laws epitomized the conservative, inward-looking and insecure nature of Irish society at the time.

The Boundary Commission

One of the outstanding issues that dominated relations between Britain and the Free State government in the early years was the issue of Northern Ireland. According to the Anglo-Irish Treaty a boundary commission was to be set up to examine the border between Northern Ireland and the Free State. During the Treaty negotiations, George had intimated that large parts of Northern Ireland would go to the Free State via a boundary commission. This was eventually set up in 1924. Eoin Mc Neill, the minister for education, represented the Free State and a Belfast lawyer; J.R Fisher represented Northern Ireland (After Craig refused to send a representative. A South African judge, Richard Feetham, was appointed chairman by the British government.

Feetham favoured minimal change, and his opinion carried great weight. Fisher kept the Northern Ireland government well informed, but it became clear that Mc Neill had done likewise with Cosgrave.

On 7 November 1925, a British newspaper, the Morning Post, carried a leaked copy of the Boundary Commission. Few alterations would actually happen as it turned out, with the Free State gaining and losing some territory. A huge controversy broke out as few in the south of Ireland had been expecting to lose territory. Eoin Mc Neill resigned from the commission and then from government as a result. Under an agreement between the Free State and British governments, the report of the Boundary commission would not be published and the border would remain unchanged. The part of the British war debt owed by the free state was cancelled.

The Boundary Commission episode was political fiasco for the Cosgrave government. This was seen as a triumph by the Northern Ireland government and James Craig, as partition now became permanent.

Free State government from 1932-1937

Governments of the Irish Free State

- Pro-Treaty Sinn Féin under William T. Cosgrave (1922-23)

- Cumann na nGaedheal under William T. Cosgrave (1923-32)

- Fianna Fáil under Éamon de Valera (1932-37)

References

Bibliography

Mansergh, Nicholas; The Irish Free State: Its Government and Politics.