Iraq War: Difference between revisions

John Leach (talk | contribs) m (Text replacement - "Ahmed Chalabi" to "Ahmed Chalabi") |

John Leach (talk | contribs) m (Text replacement - "general" to "general") |

||

| Line 690: | Line 690: | ||

Bremer and Sanchez announced the actual handover on June 28, a deliberate early transfer to avoid disruption by insurgents. Allawi was Prime Minister and Sheikh al-Yawar was President. Feith wrote that the Allawi government did no worse than the CPA; even though it was primarily made up of externals, it had legitimacy. He argues that it could have been created fourteen months earlier, and the delay was the State-CIA opposition to Chalabi.<ref>Feith, ''War and Decision'', pp. 494-495</ref> | Bremer and Sanchez announced the actual handover on June 28, a deliberate early transfer to avoid disruption by insurgents. Allawi was Prime Minister and Sheikh al-Yawar was President. Feith wrote that the Allawi government did no worse than the CPA; even though it was primarily made up of externals, it had legitimacy. He argues that it could have been created fourteen months earlier, and the delay was the State-CIA opposition to Chalabi.<ref>Feith, ''War and Decision'', pp. 494-495</ref> | ||

As Bremer left, a viceroy no longer needed, he was replaced by an [[ambassador]] accredited to the Iraqi government, [[John Negroponte]]. [[George Casey]], a four-star | As Bremer left, a viceroy no longer needed, he was replaced by an [[ambassador]] accredited to the Iraqi government, [[John Negroponte]]. [[George Casey]], a four-star general, took command of the strategic-level [[Multi-National Force-Iraq]]. Negroponte and Casey formed a good working relationship, different, however, than that of the [[United States Mission to the Republic of Vietnam]]. In the [[Vietnam War]], the military commander reported to the Ambassador, but the military and civilian sides in Iraq had parallel chains of command. | ||

===U.S. politics=== | ===U.S. politics=== | ||

There was increasing domestic opposition. A [[Out of Iraq Caucus]] formed in the [[U.S. House of Representatives]] in 2005, but there was never a major antiwar movement as there was during the [[Vietnam War]]. | There was increasing domestic opposition. A [[Out of Iraq Caucus]] formed in the [[U.S. House of Representatives]] in 2005, but there was never a major antiwar movement as there was during the [[Vietnam War]]. | ||

Revision as of 16:57, 17 March 2024

The Iraq War was the invasion of Iraq in 2003 by a multinational coalition led by the United States of America. Military operations were conducted by forces from the U.S., the United Kingdom, Australia and Poland, and was supported in various ways by many other countries, some of which allowed attacks to be launched or controlled from their territory. The United Nations neither approved nor censured the invasion, which was never a formally declared a war. The U.S. refers to it as Operation IRAQI FREEDOM. Continuing operations are under the command of Multi-National Force-Iraq.

From the U.S. operational view, Operation IRAQI FREEDOM ended when the 4th Stryker Brigade Combat Team, the last operational brigade in Iraq, left in August 2010. [1] Six other brigades actually remain, but they are called "advise and assist" units charged with training.

This war is to be distinguished from the Gulf War of 1991, following the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in 1990. The Gulf War had United Nations authorization. Further, both these wars should be differentiated from the Iran-Iraq War of 1980-1988.

The war had quick result of the removal (and later execution) of Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein and the formation of a democratically elected parliament and ratified constitution, which won UN approval. However, an amorphous insurgency since then has produced large numbers of civilian deaths and an unstable Iraqi government. It has generated enormous political controversy in the U.S. and other countries.

It also changed the dynamics of the region. According to Anthony Zinni, [2], it produced the "first Shi'a Arab state in modern history." Earlier advocates of regime change in Iraq, such as David Wurmser, had proposed replacing Saddam Hussein with a government of Iraqi exiles centered around Ahmed Chalabi; such a government would be in close alliance with Jordan.[3] There have been constant questions of Iraq splitting along the ethnic and religious lines of the three Ottoman Empire provinces from which the British Empire created it: Shi'a, Sunni, and Kurd.

Sovereignty has been transferred to a new elected Iraqi government, with U.S. forces withdrawn from the cities. Security problems still exist, although they are reduced from the worst times of the insurgency.

- See also: Iraq War, origins of invasion

- See also: Iraq War, theater operational planning

- See also: Iraq War, major combat phase

- See also: Iraq War, insurgency

- See also: Iraq War, Surge

Rationale

There had been some sentiment, in the 1991 Gulf War, that the invasion force should have continued to Baghdad and overthrown Saddam Hussein, but most agree that would have been far beyond the UN mandate and the realities of the coalition. Nevertheless, there was increasingly strong pressure among American policy influencers, from the mid-1990s on, that regime change in Iraq was important to the overall goals of American foreign policy. The 1998 Iraq Liberation Act formalized this as a Congressional statement of direction.

The main rationale for the invasion was Iraq’s continued violation of the 1991 agreement (in particular United Nations Resolution 687) that the country allow UN weapons inspectors unhindered access to nuclear facilities, as well as the country’s failure to observe several UN resolutions ordering Iraq to comply with Resolution 687. The US government cited intelligence reports that Iraq was actively supporting terrorists and developing weapons of mass destruction (WMD) as additional and acute reasons to invade. Though there was some justification before October 2002 for believing this intelligence credible, a later Senate investigation found that the intelligence was inaccurate and that the intelligence community failed to communicate this properly to the Bush administration[4].

Factors Leading Up to the Invasion

There was wide support for the view that Saddam Hussein's Iraq had a negative effect on regional and world stability, although many of the opinion makers intensely disagreed on the ways in which it was destabilizing. This idea certainly did not begin with 9/11, but 9/11 intensified the concern in the Bush Administration.[5] Nevertheless, U.S. military action against Iraq goes back to unconventional warfare during the Iran-Iraq War under Ronald Reagan, the Gulf War under George W. Bush and various operations under Bill Clinton.

Iraq had had and used chemical weapons in the Iran-Iraq War and had active missile, biological weapon and nuclear weapon development programs. These provided Saddam with both a means of threatening and deterring within the region. He also supported regional terrorists, but there is now little evidence he had operational control of terrorists acting outside the region. Saddam had attempted an assassination of former President George H. W. Bush.

The issue of non-national terrorism, however, took on new intensity after the 9/11 attack. Some analysts, such as Michael Scheuer, believe that many decision makers found it hard to accept that such an attack could come from other than a nation-state.

The Authorization for the Use of Military Force that gave the George W. Bush Administration its legal authority to attack Iraq did not specifically depend on a proven relationship between Iraq and 9-11, or a specific WMD threat to the United States. Both, however, were assumed.

Strategic preparation

Not all the planning dates may seem in proper sequence; this is not anything suspicious as some of the work was already in progress as part of routine staff activity, while other work was started by informal communications.

Even before the 9/11 attacks, regime change in Saddam Hussein's Iraq was a high priority of the George W. Bush Administration. According to This is not to suggest that previous Administrations had not been considering it, and had been steadily carrying out air attacks in support of the no-fly zones (Operation SOUTHERN WATCH and Operation NORTHERN WATCH), as well as air strikes (Operation DESERT FOX). Nevertheless, the priorities changed.

In part using the cover of the no-fly zones, in part using clandestine operations, and in part activities in areas outside Iraq, work proceeded in what is now termed Operational Preparation of the Environment. This includes Intelligence Preparation of the Battlespace, Operational Preparation of the Battlespace, and logistical and other combat support and combat service support.

Another change, in the Bush Administration, was an emphasis on not "fighting the last war". Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld was a constant advocate of transformation, emphasizing higher technology, more flexibility, and smaller forces, rather than the large heavy forces that were optimized to fight the Soviet Union. This was especially true after early operations in the Afghanistan War (2001-2021), where large U.S. ground forces were not used, but instead extensive special operations working with Afghan forces and using air power. Every war is different, however, and the reality in Afghanistan is there was an existing civil war and substantial indigenous resistance forces.

Assumed links between 9/11 and Iraq

Late in the evening of 9/11, the President had been told, by CIA chief George Tenet, that there was strong linkage to al-Qaeda and the 9/11 attack proper. Tenet did not discuss Iraq in this context. [6] On September 12, President Bush directed counterterrorism adviser Richard Clarke to review all information and reconsider if Saddam was involved in 9/11.[7]

Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz sent Rumsfeld a memo, on September 17, called "Preventing More Events"; it argued that there was a better than 1 in 10 chance that Saddam was behind 9/11. [8] He had been told, by the CIA and FBI, that there was clear linkage to al-Qaeda, but said the CIA lacked imagination. [9] On September 19, 2001, the Defense Advisory Board, chaired by Richard Perle, met for two days. Iraq was the focus. Among the speakers was Ahmed Chalabi, a controversial Iraqi exile who argued for an approach similar to the not-yet-executed approach to Afghanistan: U.S. air and other support to insurgent Iraqis. [10] Chalabi had the greatest support among Republican-identified neoconservatives, but also had Democratic supporters such as former Director of Central Intelligence R. James Woolsey.[11]

One reason Wolfowitz pushed for attacking Iraq was that he worried about what was then assumed would be a large American force in the treacherous terrain of Afghanistan. Since he believed, although without specific evidence, that there was between a 10 and 50 percent chance that Saddam was involved in 9/11, he thought Iraq, a brittle regime, might be the easier target. [12]

On the same day, Bush had told Tenet that he wanted links between Iraq and 9/11 explored. [13]

While Tenet agreed there was a connection between al-Qaeda and 9-11, and that Saddam was supporting Palestinian and European terrorists, he said that the CIA could not make a firm connection between al-Qaeda and Iraq. While CIA continued its analysis, it accepted a briefing from a Pentagon group, under Douglas Feith, to share its ideas about an Iran-9/11 connection. This was presented at CIA headquarters on August 14, 2002. According to Tenet, while Feith's team felt they had found things, in raw reports, that CIA had missed, they were not using the skills of professional intelligence analysts to consider other than the desired conclusion. His attention immediately was caught by a naval reservist working for Feith, Tina Shelton, who said the relationship between al-Qaeda and Iraq was an "open and shut case...no further analysis is required." A slide said there was a "mature, symbiotic relationship", which Tenet did not believe was supported. Pre-9/11 coordination between an al-Qaeda operative in Prague with the Iraqi intelligence service had become likely; Tenet described this association, which was later disproved, He called aside VADM Jake Jacoby, director of the Defense Intelligence Agency, and telling him he worked for Rumsfeld and Tenet, and was to remove himself from Feith's policy channels. Later, Tenet learned that the Feith team was presenting to the White House, NSC, and Office of the Vice President. [14]

It appeared a matter of certainty in the White House, especially with Cheney, that a link existed between al-Qaeda and 9/11, and Iraq War policy assumed it. A February 2007 report by the Department of Defense Inspector General said no laws were broken, but Feith's group bypassed Intelligence Community safeguards [15] On June 1, 2009, Cheney agreed that the evidence shows no direct link, but the invasion was still warranted due to Saddam's general support of terror.[16]

W. Patrick Lang, DIA national intelligence officer for the Middle East, said

The Pentagon has banded together to dominate the government’s foreign policy, and they’ve pulled it off. They’re running Chalabi. The D.I.A. has been intimidated and beaten to a pulp. And there’s no guts at all in the C.I.A.”Cite error: Closing

</ref>missing for<ref>tag

Informally, Franks had called it "Desert Storm II", using three corps as in 1991, but to force collapse of Saddam Hussein's regime. On November 27, he told the Secretary of Defense that he had a new concept, but that detailed planning would be needed. [17] Franks told Rumsfeld, during a videoconference on December 4, 2001, that it was a stale, troop-heavy concept. Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (CJCS) Dick Myers, Vice CJCS Peter Pace, and Undersecretary of Defense Douglas Feith were on the Washington end. Franks intended to ignore Feith, who he described as a "master of the off-the-wall question that rarely had relevance to operational problems." [18]

Franks proposed three basic options:

- ROBUST OPTION: Every country in the region providing support; operations from Turkey in the north, Jordan and Saudi Arabia and Kuwait in the south, air and naval bases in the Gulf states, with support bases in Egypt, Central Asia, Hungary, Romania, and Bulgaria. This would allow near-simultaneous ground and air operations.

- REDUCED OPTION: A lesser number of countries supporting would mean a sequential air and ground operation.

- UNILATERAL OPTION: If launching forces from Kuwait, U.S. ships, and U.S. aircraft from distant bases, the air and ground operations would be "absolutely sequential" due to the lack of infrastructure to bring in all ground forces at once.

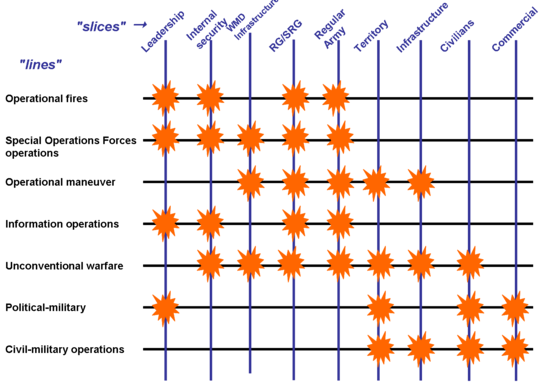

Franks wrote that during the Afghanistan planning, he had developed a technique that presented, visually, the tasks to be done ("lines of operation") and the country or resource that would be affected by these tasks ("slices"). It is not clear when he first drew this visual aid for Iraq, although it was part of the December 12 briefing to Rumsfeld; the version reproduced in his book was dated December 8.

In this model, operational fires are strikes by aircraft, artillery, and missiles. Special Operations Forces operations are principally special reconnaissance and direct action (military); unconventional warfare involves both military and CIA guerrillas. Information operations, as a line, includes psychological operations, electronic warfare, deception, and computer network operations; politicomilitary and civil-military operations are doctrinally part of information operations but are shown separately here. RG and SRG are, respectively, the Iraqi Republican Guard and Special Republican Guard elite combat formations.

Rumsfeld liked the presentation. He asked Franks what came next, and Franks said improving the forces in the region. Rumsfeld cautioned him that the President had not made the go-to-war decision, and Franks clarified that he referred to preparation:

- Triple the size of the ground forces now in Kuwait

- Increase the number of carrier strike groups in the area

- Improve infrastructure

- Discuss contingency requirements with allies

Franks said the activities could look like routine training. He pointed out that an additional 100,000 troops and 250 aircraft would not fit into Kuwait, and more basing would be needed. Rumsfeld urged that it would have to be done faster "more quickly than the military usually works". The next step was a face-to-face briefing on December 27. [19]

Rumsfeld calls for new planning

Early warning of Rumsfeld's desires came to LTC Thomas Reilly, chief of planning for Third United States Army, still based at Fort McPherson in the U.S. While Third Army would become the Coalition Forces Land Component of CENTCOM, it had not yet been so designated, when Reilly received the notice on September 13, 2001. It used the term POLO STEP, the code word for Franks' concept of operations. [20]

On October 9, 2002, GEN Eric Shinseki, Chief of Staff of the Army, told staff officers "From today forward the main effort of the US Army must be to prepare for war with Iraq". [21]

In the planning process, there were two key areas of friction between the civilians in the Department of Defense and the military:[22]

- The role of the civilians in detailed operational planning

- Caps on the number and type of troops that would be assigned

Intensified overt operations

For a number of years, the US and UK had been patrolling the "no-fly" zones of Iraq, and attacking air defense sites that directly threatened them. On September 4, 2002, however, there was a 100-aircraft strike that expanded the scope of Operation SOUTHERN WATCH, doing major damage to the H-3 and al-Baghdadi air bases near Jordan. These were more general-purpose than strictly air defense sites, and degraded a range of Iraqi capabilities. [23]

Secret operations in Iraq

The Central Intelligence Agency, as well as military special operations, conducted a wide range of activities in Iraq well before the invasion. They included Intelligence Preparation of the Battlespace such as adding intelligence collection, and Operational Preparation of the Battlespace such as destabilization and planning for using Iraqis in combat.

George Tenet, Director of Central Intelligence, had a major role in the decision to go to war, but also how it was to be fought. A lesson learned from Afghanistan was that "covert action, effectively coupled with a larger military plan, could succeed. What we were telling the vice president that day [in early 2002] was that CIA could not go it alone in toppling Saddam...in Iraq, unlike in Afghanistan, CIA's role was to provide information to the military...assess the political environment...coordinate the efforts of indigenous networks of supporters for U.S. military advances..." In February 2002, the Agency re-created the Northern Iraq Liaison Element (NILE) teams to work with the Kurds. Later, CIA officers worked to encourage surrender, but this soon proved impractical; the U.S. forces were so small that the prisoners would have outnumbered the invaders. [24]

DBANABASIS: Destabilization

At White House direction, the CIA had created a program, under the cryptonym DBANABASIS, for destabilizing Saddam. The deputy chief of the Iraq Operations Group assigned, by Deputy Director for Operations James Pavitt, to run the program, starting in late 2001, was John Maguire; the other, whose identity remains classified, is known as Luis. In the mid-nineties, CIA had found that a first coup attempt simply had gotten Iraqi CIA assets killed; Maguire had been involved in that operation, the failure of which he blamed, in large part, on Ahmed Chalabi. [25]

On February 16, 2002, the President signed a Finding authorizing ANABASIS operations. The Congressional leadership was briefed. As opposed to the 1995 plan, ANABASIS would involve considerably more lethal activities. When they mentioned, for example, destroying railroad likes, Tyler Drumheller, chief of the European Division, said "you're going to kill people if you do this." Cofer Black, director of the Counterterrorism Center, had said "the gloves are off" soon after 9/11; this was an example of that change. Again as with Afghanistan, the CIA would make the initial political contacts with the resistance groups:

- Kurdish Democratic Party headed by Massoud Barzani

- Patriotic Union of Kurdistan led by Jalal Talabani

Maguire's team entered in April, and met with both Barzani and Talabani. They met Iraqi troops who seemed eager for an American invasion. [26]

DBROCKSTARS: intelligence collection

In July 2002, a CIA team drove from Turkey to a base at Sulaymaniyah, 125 miles into Iraq from the Turkish border, and a few miles from the Iranian border. Turkey had been told that they were there primarily for collecting intelligence on Ansar al-Islam, a radical group opposed to the secular Kurdish parties, allied with al-Qaeda, and experimenting with poisons. It was based at Sargat, 25 miles from his base, at a location called Khurmal. The team was helped by Jalal Talabani's Patriotic Union of Kurdistan.

The supplementary assignment for the team, beyond Anwar al-Islam, was for covert action to overthrow Saddam. They had been ordered to penetrate the regime's military, intelligence, and security services. Confusing the situation was that they had Turkish escorts. Even with difficulties, they established liaison with a well-connected religious group, which access to the inner circles of Saddam's organizations, and irritation with the PUK. Their reports were to be identified as DBROCKSTARS. [27] By February 2003, the informants were providing significant information, including communications from Saddam's Special Security Organization. Air defense installations were confirmed and bombed. [28] 87 secure satellite telephones were made available, but, probably in early March, one asset was captured; 30 of the assets never reported again. [29]

Unconventional warfare

Franks also intensively explored the potential for military special operations, both direct action by U.S. personnel, and, as in Afghanistan, using native resistance elements. In particular, it was agreed that United States Army Special Forces teams could lead up to 10,000 Kurds in guerrilla warfare, a number large enough to be effective but not large enough to threaten Turkish sensitivity about spillover of Kurdish nationalism into Turkey. [30] The usually antagonistic KDP and PUK worked with Special Forces against units of Saddam Hussein's military at the start of the war, although [31] yhis was later to result in partitioning Kurdistan into KDP and PUK areas. There eventually was a unified Kurdistan Regional Government by 2008.

On March 15, a Kurdish group, with CIA technical assistance, derailed an Iraqi troop train by blowing up the railroad tracks, a more visible activity than expected by Washington. There were several dozen harassing attacks in Kurdistan, and a march by 20,000 protesters on Ba'ath Party headquarters in Kirkuk.[32]

JTFI: WMD intelligence

Separate from DBANABASIS was the Joint Task Force on Iraq (JTFI) in the Counterproliferation Division. Its mission was not destabilization, but precise intelligence on WMD. Valerie Plame Wilson was its operations chief. JTFI developed sources inside Iraq, but worked from outside the country. Isikoff and Corn wrote that JTFI felt accurate intelligence was important, but "Bush, Cheney, and a handful of other senior officials already believed they had enough information to know what to do about Iraq". Rumsfeld, Perle, Wolfowitz, Libby and Feith believed Saddam was the principal danger to the U.S. and "we know what we are doing." [33] They considered Saddam a greater threat than bin Laden.

Legislative authorization

Joint Resolution 114 of October 11, 2002 is the primary legislative authorization for combat operations, although some advocates of presidential authority maintained it was within the inherent powers of the Presidency.

Voting was not strictly on party lines. In the Senate, it was opposed by the Independent and some Democrats.

The House also was not on strict party lines. Voting against were:

|