Boolean algebra: Difference between revisions

imported>John R. Brews m (→Axioms) |

mNo edit summary |

||

| (51 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{subpages}} | {{subpages}} | ||

{{TOC|right}} | {{TOC|right}} | ||

A '''Boolean algebra''' is a form of logical calculus with two binary operations ''AND'' (multiplication, •) and ''OR'' (addition, +) and one unary operation ''NOT'' (negation, ~) that reverses the truth value of any statement. Boolean algebra can be used to analyze computer chips and switching circuits, as well as logical propositions. | A '''Boolean algebra''' is a form of logical calculus with two binary operations ''AND'' {{nowrap|(multiplication, •)}} and ''OR'' {{nowrap|(addition, +)}} and one unary operation ''NOT'' {{nowrap|(negation, ~)}} that reverses the truth value of any statement. Boolean algebra can be used to analyze computer chips and switching circuits, as well as logical propositions. | ||

Boolean algebra is not a portion of [[elementary algebra]] as taught in secondary schools, and is only a facet of [[algebra]], the general mathematical discipline treating variables, symbols and sets. | |||

Boolean algebra has strong connections to the ''propositional calculus'', which relates the truth value of a conclusion to the truth value of the propositions upon which it is based. However, this is only a small, and unusually simple branch of modern [[mathematical logic]].<ref name=Mendelson/> | |||

==History== | ==History== | ||

Boolean algebra was introduced in 1854 by [[George Boole]] in his book ''An Investigation of the Laws of Thought''.<ref name=Boole/> This algebra was shown in 1938 by [[Claude Shannon|Claude | Boolean algebra was introduced in 1854 by [[George Boole]] in his book ''An Investigation of the Laws of Thought''.<ref name=Boole/> This algebra was shown in 1938 by [[Claude Shannon|Claude Shannon]] to be useful in the design of logic circuits.<ref name=Shannon/> | ||

==Axioms== | ==Axioms== | ||

The operations of a Boolean algebra, namely, two binary operations on a set ''A'', ''AND'' (multiplication, •) and ''OR'' (addition, +) and one unary operation ''NOT'' (negation, ~) are supplemented by two distinguished elements | The operations of a Boolean algebra, namely, two binary operations on a set ''A'', named ''AND'' (multiplication, •) and ''OR'' (addition, +), and one unary operation ''NOT'' (negation, ~), are supplemented by two distinguished elements, namely 0 (called ''zero'') and 1 (called ''one'') that satisfy the following axioms for any subsets ''p'', ''q'', ''r'' of the set ''A'': | ||

:<math> | :<math> | ||

\begin{align} | \begin{align} | ||

| Line 16: | Line 20: | ||

\sim (\sim p) = p \ ;& \\ | \sim (\sim p) = p \ ;& \\ | ||

p \cdot p = p \quad ;& \ p\ +\ p=p \ \\ | p \cdot p = p \quad ;& \ p\ +\ p=p \ \\ | ||

\sim (p\cdot q ) = (\sim p)\ \ | \sim (p\cdot q ) = (\sim p)\ +\ (\sim q) \quad ;& | ||

\ \sim (p\ +\ q)=(\sim p) \ | \ \sim (p\ +\ q)=(\sim p)\ \cdot \ (\sim q) \quad \text { De Morgan laws} \\ | ||

p\cdot q = q \cdot p \quad ;& \ p\ + \ q =q\ + \ p \quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad \text{ Commutative laws} \ \\ | p\cdot q = q \cdot p \quad ;& \ p\ + \ q =q\ + \ p \quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad \text{ Commutative laws} \ \\ | ||

p\cdot(q \cdot r) = (p \cdot q)\cdot r \quad ;& \ p \ + \ (q \ + \ r ) = (p \ + \ q) \ + \ r \quad\quad\ \text { Associative laws}\\ | p\cdot(q \cdot r) = (p \cdot q)\cdot r \quad ;& \ p \ + \ (q \ + \ r ) = (p \ + \ q) \ + \ r \quad\quad\ \text { Associative laws}\\ | ||

| Line 27: | Line 31: | ||

The above axioms are redundant, and all can be proven using only the ''identity'', ''complement'', ''commutative'' and ''distributive'' laws. The distributive law: | The above axioms are redundant, and all can be proven using only the ''identity'', ''complement'', ''commutative'' and ''distributive'' laws. The distributive law: | ||

:<math>\ p \ + \ \left( q \cdot r \right) \ = \left( p \ + \ q \right) \cdot \left( p \ + \ r \right) \ , </math> | :<math>\ p \ + \ \left( q \cdot r \right) \ = \left( p \ + \ q \right) \cdot \left( p \ + \ r \right) \ , </math> | ||

may seem at variance with the | may seem at variance with the laws for elementary algebra, which would state: | ||

:<math> \left( p \ + \ q \right) \cdot \left( p \ + \ r \right) = p\cdot p \ +\ p\cdot r \ +\ q \cdot p \ +\ q\cdot r \ .</math> | :<math> \left( p \ + \ q \right) \cdot \left( p \ + \ r \right) = p\cdot p \ +\ p\cdot r \ +\ q \cdot p \ +\ q\cdot r \ .</math> | ||

However, this expression is equivalent within the Boolean axioms above. From the other axioms, ''p·p = p''. Also, {{nowrap|''p·r + q·p}} = {{nowrap|p·(q + r)''.}} This set lies within ''p'', so intuitively {{nowrap|''p + p·(q + r)}} = p''. Using the Boolean axioms instead of intuition, {{nowrap|''p + p·(q + r)}} = {{nowrap|p·(1 + q + r)''}} and according to the properties of ‘''1''’, {{nowrap|''(1 + q + r)}} = 1''. Thus, the | However, this expression is equivalent within the Boolean axioms above. From the other axioms, ''p·p = p''. Also, {{nowrap|''p·r + q·p}} = {{nowrap|p·(q + r)''.}} This set lies within ''p'', so intuitively {{nowrap|''p + p·(q + r)}} = p''. Using the Boolean axioms instead of intuition, {{nowrap|''p + p·(q + r)}} = {{nowrap|p·(1 + q + r)''}} and according to the properties of ‘''1''’, {{nowrap|''(1 + q + r)}} = 1''. Thus, the elementary algebraic result, when interpreted in terms of the Boolean axioms, reduces to the Boolean distributive law. | ||

[[Venn diagram]]s provide a graphical visualization of | ==Alternative notations== | ||

Some alternative notations for the operations of Boolean algebra include the following: | |||

::<math>\mathit{AND: }\quad \ A\cdot B,\ A \and B, \ A </math><big> ''&&'' </big><math>B,\ A</math><big> ''&'' </big><math> B,\ A\cap B </math> | |||

::<math> | |||

\begin{align} | |||

\mathit{OR: }& \quad A + B, \ A \or B, \ A \mathit{||} B, \ A|B,\ A\cup B \\ | |||

\mathit{NOT: }& \quad \sim A,\ \overline {A} ,\ \ A',\ \neg A, \ !A \\ | |||

\end{align} | |||

</math> | |||

==Venn diagrams== | |||

{{Image|Boolean operations.PNG|right|200px|Interpretation of Boolean operations using Venn diagrams.}} | |||

{{main|Venn diagram}} | |||

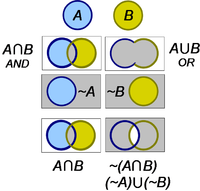

[[Venn diagram]]s provide a graphical visualization of the Boolean operations.<ref name=Whitesitt/> The ''intersection'' of two sets ''A∩B'' plays the role of the ''AND'' operation and the ''union'' of two sets ''A<big>∪</big>B'' represents the ''OR'' function, as shown by gray shaded areas in the figure. To introduce the ''NOT'' operation, the universal set is represented by the rectangle, so ''~A'' is the set of everything not included in ''A'', corresponding to the gray portion of the rectangle in the third panel on the left. | |||

These diagrams provide a visualization of the Boolean axioms as well. For example, the depiction of ''~(A∩B)'' is readily seen to be the same as ''(~A)<big>∪</big>(~B)'', as required by the De Morgan axiom. | |||

==Truth tables== | |||

A [[truth table]] for a logical proposition is a formal way to find whether a conclusion is valid or invalid, with ‘0’ corresponding to "invalid" and ‘1’ to "valid". In the context of Boolean algebra, attention is focused upon ''Boolean functions'', denoted ''f(A, B, C)'', where variables ''A, B, C'' and function ''f'' are allowed values ‘1’ or ‘0’ according as the statements they correspond to are valid or invalid. The truth table for ''f'' is simply a tabulation of the values of ''f'' for all possible values of ''A, B, C''. For example, suppose: | |||

:<math>f=\sim\!A+B\cdot C \ . </math> | |||

The corresponding truth table is below at the left: | |||

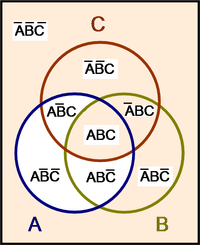

{{Image|Venn for logic function.PNG|right|200px|Venn diagram for ''f <nowiki>=</nowiki> ~A + B·C''.}} | |||

{| class="wikitable" style=" text-align:center;" | |||

|+ '''f = ~A + B·C''' | |||

|- | |||

! style="width:15%" | ''A'' | |||

! style="width:15%" | ''B'' | |||

! style="width:15%" | ''C'' | |||

! style="width:15%" | ''f=~A + B·C'' | |||

|- | |||

| 0 || 0 || 0 || style="background:papayawhip; color:blue;font-weight:bold" | 1 | |||

|- | |||

| 0 || 0 ||style="background:papayawhip" | 1 || style="background:papayawhip; color:blue;font-weight:bold" | 1 | |||

|- | |||

| 0 ||style="background:papayawhip" | 1 || 0 ||style="background:papayawhip; color:blue;font-weight:bold"| 1 | |||

|- | |||

| 0 ||style="background:papayawhip" | 1 || style="background:papayawhip" | 1 || style="background:papayawhip; color:blue;font-weight:bold" | 1 | |||

|- | |||

| style="background:papayawhip" | 1 ||0 || 0 || style="color:blue;font-weight:bold"|0 | |||

|- | |||

|- | |||

| style="background:papayawhip" | 1 ||0|| style="background:papayawhip" | 1 || style=" color:blue;font-weight:bold"|0 | |||

|- | |||

| style="background:papayawhip" | 1 ||style="background:papayawhip" | 1 || 0 || style=" color:blue;font-weight:bold"|0 | |||

|- | |||

| style="background:papayawhip" | 1 ||style="background:papayawhip" | 1 || style="background:papayawhip" | 1 || style="background:papayawhip; color:blue;font-weight:bold" | 1 | |||

|- | |||

|} | |||

The truth table can be set in correspondence with a [[Venn diagram]], as shown to the right. The truth table entry ‘0’ under column ''A'' is interpreted as a set of points ''not'' in ''A'', while an entry of ‘1’ is taken to refer to points that are contained in ''A''. In the diagram, the notation ''Ā'' for ''~A'' is used to keep labeling compact, and the ‘·’ for intersection is omitted. Labels designate the regions with boundaries surrounding the label, so label ''ABC'' denotes the region common to all three sets ''A'', ''B'' and ''C''. The colored area encompasses all points corresponding to ''f = 1'', that is all points in the region ''~A + B·C'', while the white space corresponds to areas outside this region. | |||

In effect, ''A'', ''B'', ''C'' are the statements: | |||

*A: Point ''p'' is in set ''A'' | |||

*B: Point ''p'' is in set ''B'' | |||

*C: Point ''p'' is in set ''C'' | |||

and proposition ''f'' is: | |||

*f: Point ''p'' is either common to sets ''B'' and ''C'' or not in set ''A''. | |||

The truth table and the Venn diagram decide the validity of ''f'' for all choices for validity of ''A'', ''B'', and ''C''. | |||

The Boolean function ''f'' can be used with other statements that are closer to everyday language, for example, by substituting concrete entities for the various sets. | |||

*A : The set of smart people | |||

*B : The set of politicians | |||

*C : The set of crooks | |||

Then should Bill be smart and a crooked politician (A·B·C), he would fall into the group ''f'': | |||

*f : ~A + B·C'', | |||

a combination of stupid people and crooked politicians (of any capacity), making Bill a Democrat or a Republican, a Liberal or a Conservative, depending upon the country, the speaker and the epoch. | |||

==Extension to logic== | |||

The above discussion outlines a method for describing various sets and their subsets, and provides a formal system for deciding when different descriptions of a subset are equivalent. The application of this system to the analysis of logical arguments requires connections to constructions such as "if ''A'', then ''B''", sometimes called ''conditionals''. Assuming the statements ''A'' and ''B'' are either ''true'' ‘1’ or ''false'' ‘0’ the conditional "implies", denoted by ‘→’ can be defined by the truth table: | |||

{| class="wikitable" style=" text-align:center;" | |||

|+ '''A → B''' | |||

|- | |||

! style="width:15%" | ''A'' | |||

! style="width:15%" | ''B'' | |||

! style="width:15%" | ''A → B'' | |||

|- | |||

| 0 || 0 || style="background:papayawhip; color:blue;font-weight:bold" | 1 | |||

|- | |||

| 0 ||style="background:papayawhip" | 1 || style="background:papayawhip; color:blue;font-weight:bold" | 1 | |||

|- | |||

|style="background:papayawhip" | 1 || 0 ||style="color:blue;font-weight:bold"| 0 | |||

|- | |||

| style="background:papayawhip" | 1 || style="background:papayawhip" | 1 || style="background:papayawhip; color:blue;font-weight:bold" | 1 | |||

|- | |||

|} | |||

In other words, ''A → B'' is false when and only when ''A'' is true and ''B'' is false. This truth table is the same as ''~A + B''. As an example, we could take: | |||

*A: The ball is tossed. | |||

*B: The dog runs. | |||

Then ''A → B'' means the dog always runs when the ball is tossed, but the dog may run otherwise as well, or not. | |||

The ''biconditional'' "equivalence" denoted by ‘↔’ can be defined by the truth table: | |||

{| class="wikitable" style=" text-align:center;" | |||

|+ '''A ↔ B''' | |||

|- | |||

! style="width:15%" | ''A'' | |||

! style="width:15%" | ''B'' | |||

! style="width:15%" | ''A ↔ B'' | |||

|- | |||

| 0 || 0 || style="background:papayawhip; color:blue;font-weight:bold" | 1 | |||

|- | |||

| 0 ||style="background:papayawhip" | 1 || style= "color:blue;font-weight:bold" | 0 | |||

|- | |||

|style="background:papayawhip" | 1 || 0 ||style="color:blue;font-weight:bold"| 0 | |||

|- | |||

| style="background:papayawhip" | 1 || style="background:papayawhip" | 1 || style="background:papayawhip; color:blue;font-weight:bold" | 1 | |||

|- | |||

|} | |||

Thus, ''A ↔ B'' has the same truth table as ''(A → B)•(B → A)''. As an example, we could take: | |||

*A: The switch is closed. | |||

*B: The light is on. | |||

Then ''A ↔ B'' means the light is on if, and only if, the switch is closed. As this example shows, formal logic, like all mathematics, has to be related carefully to reality, and ignoring fuses and burned-out bulbs may or may not be an adequate model for the real situation. | |||

With antecedents ''A'' and consequents ''B'' related by implication and equivalence, logical constructions can be analyzed. What can be accomplished is to determine whether various combinations of statements imply or are equivalent to various other combinations of statements; provided, of course, that the statements involved are individually either ''true'' or ''false''. | |||

A practical application of this formalism is to switching arrays and logic circuits, where the equivalence of different networks can be established, enabling the selection of the simplest implementation for a chosen function. | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| Line 38: | Line 171: | ||

<ref name=Boole> | <ref name=Boole> | ||

{{cite book |title=An investigation of the laws of thought, on which are founded the mathematical theories of logic and probabilities |author=George Boole |publisher=Macmillan and Co. |year=1854 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=ZBkPAAAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover}} | {{cite book |title=An investigation of the laws of thought, on which are founded the mathematical theories of logic and probabilities |author=George Boole |publisher=Macmillan and Co. |year=1854 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=ZBkPAAAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover}} | ||

</ref> | |||

<ref name=Mendelson> | |||

{{cite book |title=Schaum's Outline of Boolean Algebra and Switching Circuits |author=Elliott Mendelson |isbn=0070414602 |publisher=McGraw-Hill |year=1970 |url=http://www.amazon.com/Schaums-Outline-Boolean-Switching-Circuits/dp/0070414602/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1310999755&sr=1-1#reader_0070414602 |chapter=Chapter 1: The algebra of logic }} | |||

</ref> | </ref> | ||

| Line 44: | Line 181: | ||

</ref> | </ref> | ||

}} | <ref name=Whitesitt> | ||

For a discussion, see {{cite book |title=Boolean algebra and its applications |author=J. Eldon Whitesitt |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=VDIuSvrDVxwC&pg=PA5 |pages=pp. 5 ''ff'' |chapter=§1-4: Venn diagrams |isbn=0486684830 |publisher=Courier Dover Publications |year=1995 |edition=Republication of Addison-Wesley 1961 ed}} | |||

</ref> | |||

}}[[Category:Suggestion Bot Tag]] | |||

Latest revision as of 11:00, 20 July 2024

A Boolean algebra is a form of logical calculus with two binary operations AND (multiplication, •) and OR (addition, +) and one unary operation NOT (negation, ~) that reverses the truth value of any statement. Boolean algebra can be used to analyze computer chips and switching circuits, as well as logical propositions.

Boolean algebra is not a portion of elementary algebra as taught in secondary schools, and is only a facet of algebra, the general mathematical discipline treating variables, symbols and sets.

Boolean algebra has strong connections to the propositional calculus, which relates the truth value of a conclusion to the truth value of the propositions upon which it is based. However, this is only a small, and unusually simple branch of modern mathematical logic.[1]

History

Boolean algebra was introduced in 1854 by George Boole in his book An Investigation of the Laws of Thought.[2] This algebra was shown in 1938 by Claude Shannon to be useful in the design of logic circuits.[3]

Axioms

The operations of a Boolean algebra, namely, two binary operations on a set A, named AND (multiplication, •) and OR (addition, +), and one unary operation NOT (negation, ~), are supplemented by two distinguished elements, namely 0 (called zero) and 1 (called one) that satisfy the following axioms for any subsets p, q, r of the set A:

The above axioms are redundant, and all can be proven using only the identity, complement, commutative and distributive laws. The distributive law:

may seem at variance with the laws for elementary algebra, which would state:

However, this expression is equivalent within the Boolean axioms above. From the other axioms, p·p = p. Also, p·r + q·p = p·(q + r). This set lies within p, so intuitively p + p·(q + r) = p. Using the Boolean axioms instead of intuition, p + p·(q + r) = p·(1 + q + r) and according to the properties of ‘1’, (1 + q + r) = 1. Thus, the elementary algebraic result, when interpreted in terms of the Boolean axioms, reduces to the Boolean distributive law.

Alternative notations

Some alternative notations for the operations of Boolean algebra include the following:

- && &

Venn diagrams

Venn diagrams provide a graphical visualization of the Boolean operations.[4] The intersection of two sets A∩B plays the role of the AND operation and the union of two sets A∪B represents the OR function, as shown by gray shaded areas in the figure. To introduce the NOT operation, the universal set is represented by the rectangle, so ~A is the set of everything not included in A, corresponding to the gray portion of the rectangle in the third panel on the left.

These diagrams provide a visualization of the Boolean axioms as well. For example, the depiction of ~(A∩B) is readily seen to be the same as (~A)∪(~B), as required by the De Morgan axiom.

Truth tables

A truth table for a logical proposition is a formal way to find whether a conclusion is valid or invalid, with ‘0’ corresponding to "invalid" and ‘1’ to "valid". In the context of Boolean algebra, attention is focused upon Boolean functions, denoted f(A, B, C), where variables A, B, C and function f are allowed values ‘1’ or ‘0’ according as the statements they correspond to are valid or invalid. The truth table for f is simply a tabulation of the values of f for all possible values of A, B, C. For example, suppose:

The corresponding truth table is below at the left:

| A | B | C | f=~A + B·C |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

The truth table can be set in correspondence with a Venn diagram, as shown to the right. The truth table entry ‘0’ under column A is interpreted as a set of points not in A, while an entry of ‘1’ is taken to refer to points that are contained in A. In the diagram, the notation Ā for ~A is used to keep labeling compact, and the ‘·’ for intersection is omitted. Labels designate the regions with boundaries surrounding the label, so label ABC denotes the region common to all three sets A, B and C. The colored area encompasses all points corresponding to f = 1, that is all points in the region ~A + B·C, while the white space corresponds to areas outside this region.

In effect, A, B, C are the statements:

- A: Point p is in set A

- B: Point p is in set B

- C: Point p is in set C

and proposition f is:

- f: Point p is either common to sets B and C or not in set A.

The truth table and the Venn diagram decide the validity of f for all choices for validity of A, B, and C.

The Boolean function f can be used with other statements that are closer to everyday language, for example, by substituting concrete entities for the various sets.

- A : The set of smart people

- B : The set of politicians

- C : The set of crooks

Then should Bill be smart and a crooked politician (A·B·C), he would fall into the group f:

- f : ~A + B·C,

a combination of stupid people and crooked politicians (of any capacity), making Bill a Democrat or a Republican, a Liberal or a Conservative, depending upon the country, the speaker and the epoch.

Extension to logic

The above discussion outlines a method for describing various sets and their subsets, and provides a formal system for deciding when different descriptions of a subset are equivalent. The application of this system to the analysis of logical arguments requires connections to constructions such as "if A, then B", sometimes called conditionals. Assuming the statements A and B are either true ‘1’ or false ‘0’ the conditional "implies", denoted by ‘→’ can be defined by the truth table:

| A | B | A → B |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

In other words, A → B is false when and only when A is true and B is false. This truth table is the same as ~A + B. As an example, we could take:

- A: The ball is tossed.

- B: The dog runs.

Then A → B means the dog always runs when the ball is tossed, but the dog may run otherwise as well, or not.

The biconditional "equivalence" denoted by ‘↔’ can be defined by the truth table:

| A | B | A ↔ B |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

Thus, A ↔ B has the same truth table as (A → B)•(B → A). As an example, we could take:

- A: The switch is closed.

- B: The light is on.

Then A ↔ B means the light is on if, and only if, the switch is closed. As this example shows, formal logic, like all mathematics, has to be related carefully to reality, and ignoring fuses and burned-out bulbs may or may not be an adequate model for the real situation.

With antecedents A and consequents B related by implication and equivalence, logical constructions can be analyzed. What can be accomplished is to determine whether various combinations of statements imply or are equivalent to various other combinations of statements; provided, of course, that the statements involved are individually either true or false.

A practical application of this formalism is to switching arrays and logic circuits, where the equivalence of different networks can be established, enabling the selection of the simplest implementation for a chosen function.

References

- ↑ Elliott Mendelson (1970). “Chapter 1: The algebra of logic”, Schaum's Outline of Boolean Algebra and Switching Circuits. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0070414602.

- ↑ George Boole (1854). An investigation of the laws of thought, on which are founded the mathematical theories of logic and probabilities. Macmillan and Co..

- ↑ For example, see Jonathan Sterne (2003). “Shannon, Claude (1916-2001)”, Steve Jones, ed: Encyclopedia of new media: an essential reference to communication and technology. SAGE Publications, p. 406. ISBN 0761923829.

- ↑ For a discussion, see J. Eldon Whitesitt (1995). “§1-4: Venn diagrams”, Boolean algebra and its applications, Republication of Addison-Wesley 1961 ed. Courier Dover Publications, pp. 5 ff. ISBN 0486684830.