Gadsden Purchase: Difference between revisions

John Leach (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| (One intermediate revision by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

==Origins== | ==Origins== | ||

In 1846 at the start of the [[Mexican-American War]], [[James Gadsden]] of [[Charleston]], [[South Carolina]], championed a southern cross-country railroad in 1846 to improve his hometown's [[economy]] and to export [[slavery]] west of [[Texas (U.S. state)|Texas]]. | In 1846 at the start of the [[Mexican-American War]], [[James Gadsden]] of [[Charleston]], [[South Carolina (U.S. state)|South Carolina]], championed a southern cross-country railroad in 1846 to improve his hometown's [[economy]] and to export [[slavery]] west of [[Texas (U.S. state)|Texas]]. | ||

At the urging of Senator [[Jefferson Davis]], Gadsden was appointed Minister to Mexico by President [[Franklin Pierce]] and in July 1853, he obtained formal permission from Pierce to make a treaty that would settle border issues and private claims and, especially, secure enough territory for the proposed southern railroad route. Financial needs of the administration of [[Antonio López de Santa Anna]] aided negotiation of a treaty whereby territory in northern Mexico was sold to the United States. Article XI of the [[Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo]] was abrogated, but the United States was to aid in suppressing Indian attacks across the border. For these concessions the United States was to pay Mexico $15 million and assume all claims of its citizens against Mexico. The U.S. promised to cooperate in suppressing filibustering expeditions. | At the urging of Senator [[Jefferson Davis]], Gadsden was appointed Minister to Mexico by President [[Franklin Pierce]] and in July 1853, he obtained formal permission from Pierce to make a treaty that would settle border issues and private claims and, especially, secure enough territory for the proposed southern railroad route. Financial needs of the administration of [[Antonio López de Santa Anna]] aided negotiation of a treaty whereby territory in northern Mexico was sold to the United States. Article XI of the [[Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo]] was abrogated, but the United States was to aid in suppressing Indian attacks across the border. For these concessions the United States was to pay Mexico $15 million and assume all claims of its citizens against Mexico. The U.S. promised to cooperate in suppressing filibustering expeditions. | ||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

<references/> | <references/>[[Category:Suggestion Bot Tag]] | ||

Latest revision as of 16:01, 19 August 2024

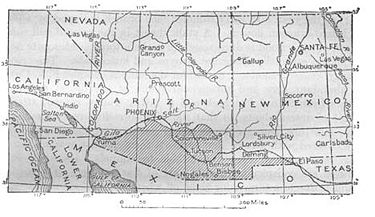

The Gadsden Purchase or Gadsden Treaty (in Mexico, called the Mesilla Treaty ) of 1853 was the acquisition by the United States of America from Mexico of 29.1 million acres in a strip of borderland for $10 million. The area became part of Arizona and New Mexico, and was essential for a southern transcontinental route that was used for the Southern Pacific Railroad. The chief city is Tucson, Arizona.

Origins

In 1846 at the start of the Mexican-American War, James Gadsden of Charleston, South Carolina, championed a southern cross-country railroad in 1846 to improve his hometown's economy and to export slavery west of Texas.

At the urging of Senator Jefferson Davis, Gadsden was appointed Minister to Mexico by President Franklin Pierce and in July 1853, he obtained formal permission from Pierce to make a treaty that would settle border issues and private claims and, especially, secure enough territory for the proposed southern railroad route. Financial needs of the administration of Antonio López de Santa Anna aided negotiation of a treaty whereby territory in northern Mexico was sold to the United States. Article XI of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was abrogated, but the United States was to aid in suppressing Indian attacks across the border. For these concessions the United States was to pay Mexico $15 million and assume all claims of its citizens against Mexico. The U.S. promised to cooperate in suppressing filibustering expeditions.

Treaty

The treaty was signed by Pierce and Santa Anna but needed to be ratified by 2/3 vote of the U.S. Senate, where it met strong opposition. Antislavery senators opposed further acquisition of slave territory. Lobbying by speculators gave the treaty a bad reputation. Some senators objected to furnishing Santa Anna financial assistance. The Senate amended the treaty by reducing the territory to be acquired from 55,000 square miles to the area essential for the railroad route. All mention of private claims and filibustering expeditions was deleted. The payment to Mexico was lowered to $10 million. There was much talk of corruption and payments by railroad speculators and land speculators. The Senate by a narrow margin ratified the treaty on April 25, 1854 and it went into effect June 30, 1854.

Impact

The residents of the area gained full U.S. citizenship. The principal threat to the peace and security of settlers and travelers in the area were raids by Apache Indians. The U.S. Army took control of the purchase lands in 1854 but not until 1856 were troops stationed in the troubled region. In June of 1857 it established Fort Buchanan south of the Gila at the head of the Sonoita Creek Valley. The fort protected the area until it was evacuated and destroyed in July 1861.[1] The new stability brought miners and ranchers. By the late 1850s, mining camps and military posts had not only transformed the Arizona countryside; they had also generated new trade linkages to the province of Sonora, Mexico. Magdalena, Sonora, became a supply center for Tubac, wheat from nearby Cucurpe fed the troops at Fort Buchanan, and the town of Santa Cruz sustained the Mowry mines, just miles to the north.

After the Gadsden Purchase, southern Arizona's social elite, including the Estevan Ochoa, Mariano Samaniego, and Leopoldo Carillo families, remained primarily Mexican American until the coming of the railroad in the 1880s.[2] When the Sonora Exploring and Mining Company opened silver mines in southern Arizona, it sought to employ educated, middle-class Americans who shared a work ethic and leadership abilities to operate the mines. A biographical analysis of some 200 of its employees, classed as capitalists, managers, laborers, and general service personnel, reveals that the resulting work force included Europeans, Americans, Mexicans, and Indians. This mixture failed to stabilize the remote area, which lacked formal social, political, and economic organization in the years from the Gadsden Purchase to the Civil War.[3]

From the late 1840s into the 1870s Texas stockmen drove their beef cattle over southern Arizona on the Texas-California trail. Texans were impressed with the grazing possibilities offered by the Gadsden Purchase country of Arizona. By the last third of the century they were moving their herds into Arizona and establishing the range cattle industry there. Not only did the Texans contribute their proven range methods to the new grass country of Arizona but their problems as well. Texas rustlers brought lawlessness, poor management resulted in overstocking, and carelessness introduced destructive diseases. But these difficulties did force laws and associations in Arizona to curb and resolve them. The Anglo-American cattleman frontier in Arizona was an extension of the Texas experience.[4]

In 1882 the Southern Pacific railway was finally completed through the purchased territory.

References

- ↑ Ben Sacks, "The Origins of Fort Buchanan: Myth and Fact." Arizona and the West 1965 7(3): 207-226. Issn: 0004-1408

- ↑ Thomas E. Sheridan, "Peacock in the Parlor: Frontier Tucson's Mexican Elite." Journal of Arizona History 1984 25(3): 245-264. Issn: 0021-9053

- ↑ Diane North, "'A Real Class of People' in Arizona: a Biographical Analysis of the Sonora Exploring and Mining Company, 1856-1863." Arizona and the West 1984 26(3): 261-274. Issn: 0004-1408

- ↑ James A. Wilson, "West Texas Influence on the Early Cattle Industry of Arizona." Southwestern Historical Quarterly 1967 71(1): 26-36. Issn: 0038-478x