imported>Chunbum Park |

imported>John Stephenson |

| (38 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) |

| Line 1: |

Line 1: |

| == '''[[Battleship]]''' ==

| | {{:{{FeaturedArticleTitle}}}} |

| ----

| | <small> |

| [[Image:USS Massachusetts BB-59 Fall RIver.jpg|thumb|right|180px|{{USS Massachusetts BB-59 Fall RIver.jpg/credit}}<br />The [[USS Massachusetts (BB-59)|USS ''Massachusetts'' (BB-59)]] or "Big Mamie," on display as a museum ship in Battleship Cove, [[Fall River, Massachusetts]].]]

| | ==Footnotes== |

| The '''battleship''', though now essentially obsolete as a naval weapon, is a naval vessel intended to engage the most powerful warships of an opposing navy. Evolved from the [[ship of the line]], their main armament consisted of multiple heavy [[cannon]] mounted in movable [[turret]]s. The ships boasted extensive armor and as such were designed to survive severe punishment inflicted upon them by other capital ships.

| |

| | |

| The word "battleship" was coined around 1794 and is a contraction of the phrase "line-of-battle ship," the dominant wooden warship during the [[Age of Sail]].<ref name="OED">"battleship" The Oxford English Dictionary. 2nd ed. 1989. OED Online. Oxford University Press. 4 April 2000.</ref> The term came into formal use in the late 1880s to describe a specific type of [[ironclad warship]] (now referred to by historians as pre-''Dreadnought'' battleships).<ref name="Stoll">Stoll, J. ''Steaming in the Dark?'', Journal of Conflict Resolution Vol. 36 No. 2, June 1992.</ref> In 1906, the commissioning of [[HMS Dreadnought (1905)|HMS ''Dreadnought'']] heralded a revolution in capital ship design. Subsequent battleship designs were therefore referred to as "dreadnoughts." A general criterion from thereon in was that the armor of a true battleship must be sufficiently thick to withstand a hit by its own most powerful gun, within certain constraints. [[#The Diversion of the Battlecruiser|Battlecruiser]]s, while having near-battleship-sized guns, did not meet this standard of protection, and instead were intended to be fast enough to outrun the more heavily armed and armored battleship.<ref name=Massie>{{citation

| |

| | author = Robert K. Massie

| |

| | title = Dreadnought: Britain, Germany and the Coming of the Great War

| |

| | publisher = Ballantine

| |

| | year = 1992

| |

| | isbn = 9780345375568}}</ref>

| |

| | |

| From 1905 to the early 1940s, battleships defined the strength of a first-class navy. The idea of a strong "fleet in being", backed by a major industrial infrastructure, was key to the thinking of the naval strategist per [[Alfred Thayer Mahan]], writing in his 1890 book, ''The Influence of Sea Power upon History, 1660-1763'' (1890). The essence of Mahan from a naval viewpoint is that a great navy is a mark and prerequisite of national greatness. In a 1912 letter to the ''New York Times'', he counseled against relying on international relations for peace, and pointed out that other major nations were all building battleships.<ref>{{citation

| |

| | title =HOPELESSLY OUTFORCED."; Admiral Mahan Prophesies Plight of Nation Without More Battleships.

| |

| | author = [[Alfred Thayer Mahan]]

| |

| | date = 14 April 1912

| |

| | journal = New York Times

| |

| | url = http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free/pdf?_r=1&res=9503E5DF103AE633A25757C1A9629C946396D6CF}}</ref>

| |

| Asymmetrical threats to battleships began, in the early 20th century, with [[torpedo]]es from [[fast attack craft]] and [[mine (naval)|mines]]. These [[#The underwater threat|underwater threats]] could strike in more vulnerable spots than could heavy guns. [[#Aircraft versus battleship|Aircraft]], however, became an even more decisive threat by World War II.

| |

| | |

| ''[[Battleship|.... (read more)]]''

| |

| | |

| {| class="wikitable collapsible collapsed" style="width: 90%; float: center; margin: 0.5em 1em 0.8em 0px;"

| |

| |-

| |

| ! style="text-align: center;" | [[Battleship#References|notes]]

| |

| |-

| |

| |

| |

| {{reflist|2}} | | {{reflist|2}} |

| |}

| | </small> |

Latest revision as of 09:19, 11 September 2020

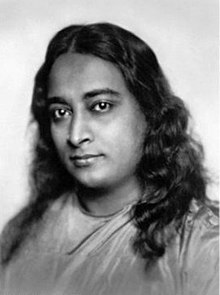

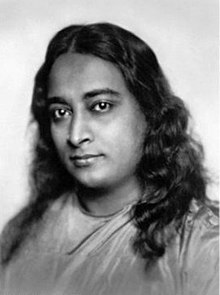

Paramhansa Yogananda circa 1920.

Paramhansa Yogananda (5 Jan 1893–7 Mar 1952) was one of the first Indian teachers from the Hindu spiritual tradition to reside permanently in the West, and in particular, he was the first to teach yoga to Americans. He emphasized the universality of the great religions, and ceaselessly taught that all religions, especially Hinduism and Christianity, were essentially the same in their essence. The primary message of Yogananda was to practice the scientific technique of kriya yoga to be released from all human suffering.

He emigrated from India to the United States in 1920 and eventually founded the Self-Realization Fellowship there in Los Angeles, California. He published his own life story in a book called Autobiography of a Yogi, first published in 1946. In the book, Yogananda provided some details of his personal life, an introduction to yoga, meditation, and philosophy, and accounts of his world travels and encounters with a wide variety of saints and colorful personalities, including Therese Neumann, Mohandas K. Gandhi, Luther Burbank, and Jagadis C. Bose.

Paramhamsa, also spelled Paramahamsa, is a Sanskrit title used for Hindu spiritual teachers who have become enlightened. The title of Paramhansa originates from the legend of the swan. The swan (hansa) is said to have a mythical ability to sip only the milk from a water-and-milk mixture, separating out the more watery part. The spiritual master is likewise said to be able to live in a world like a supreme (param) swan, and only see the divine, instead of all the evil mixed in there too, which the worldly person sees.

Yogananda is considered by his followers and many religious scholars to be a modern avatar.

In 1946, Yogananda published his Autobiography of a Yogi. It has since been translated into 45 languages, and in 1999 was designated one of the "100 Most Important Spiritual Books of the 20th Century" by a panel of spiritual authors convened by Philip Zaleski and HarperCollins publishers.

Awake: The Life of Yogananda is a 2014 documentary about Paramhansa Yogananda, in English with subtitles in seventeen languages. The documentary includes commentary by George Harrison and Ravi Shankar, among others.[1][2]