Nero: Difference between revisions

imported>Richard Nevell (The end of Octavia) |

mNo edit summary |

||

| (10 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{subpages}} | {{subpages}} | ||

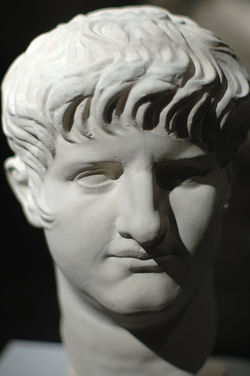

{{Image|Nero bust.jpg|thumb|250px | {{Image|Nero bust (young).jpg|thumb|250px|A bust of the Emperor Nero. As shown here he was often depicted with curled hair fashioned after similar haircuts worn by actors and charioteers.<ref>Griffin, Miriam T. (1987). ''Nero: The End of a Dynasty''. London: Routledge. p. 121. ISBN 978-0415214643.</ref>}} | ||

'''Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus''', commonly referred to as '''Nero''', was [[Roman Emperor]] from A.D. 54 to | '''Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus''', commonly referred to as '''Nero''', was [[Roman Emperor]] from A.D. 54 to A.D. 68. His mother married the Emperor [[Claudius]] in A.D. 49 and the following year the Emperor adopted Nero as his son. On Claudius' death in A.D. 54 Nero was proclaimed Emperor by the Praetorian Guard, becoming the youngest Roman Emperor in history. His mother was influential in ensuring Nero succeeded Claudius, though he later had her murdered. | ||

One of the most famous events of Nero's reign was the [[Great Fire of Rome]] in A.D. 64. The city was devastated by the fire, and in the aftermath Nero cleared some of the damaged areas to built his Golden Palace. The expensive building was unpopular at the time, and there was speculation that Nero had arranged the fire himself so he could construct the palace. Nero was unpopular amongst the upper classes, and a rebellion in A.D. 68 led to the end of Nero's reign, and on 9 June he committed suicide by stabbing himself in the neck. He was succeeded by [[Servius Sulpicius Galba]] who had joined the rebellion against him. | |||

==Early life (A.D. 37–54)== | |||

The surviving literature from the Roman world is united in the opinion that Nero was a tyrant. For instance [[Pliny the Elder]] wrote that Nero was "the destroyer of the human race". For later historians, Italian in particular, he was considered the archetypal despot along with figures such as Caligula. In Christian writings Nero was considered the [[Anti-Christ]], an opinion which gained popularity as Christianity became a mainstream religion. Nero's notoriety persisted over the following centuries (he was reference in the play ''[[Hamlet]]''), and amongst modern historians it is considered that Nero's personality contributed to the rebellion which led to his downfall.<ref>Griffin, ''Nero: The End of a Dynasty'', 15–16.</ref> | {{Image|Claudius bust.jpg|left|200px|A bust of the Emperor [[Claudius]] who adopted Nero as his son}} | ||

Nero was born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus in A.D. 37, during the reign of [[Caligula]]; he was the son of Julia Agrippina and Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus. Julia's father, Germanicus Caesar, had been adopted by the Emperor [[Tiberius]] and the people of Rome felt that the family were the heirs of [[Augustus]], who had himself adopted Tiberius. Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus died in A.D. 39 and Agrippina was exiled the same year, taking her son with her. When Claudius became Emperor in A.D. 41 he recalled Agrippina and Lucius to Rome.<ref>Shotter, David (2005). ''Nero'', 2nd edition. London: Routledge. pp. 10–11. ISBN 0-415-31941-2.</ref> Claudius' wife, [[Messallina]], began an affair and with her lover plotted to assassinate the Emperor. The plan was discovered in A.D. 48 and Messallina committed suicide, leaving behind two children from her marriage to Claudius: a girl, Octavia, and a boy, Britannicus. The following year Agrippina married Claudius, who was her uncle.<ref>Griffin, ''Nero: The End of a Dynasty'', pp. 28–29.</ref> In A.D. 49 the philosopher [[Lucius Annaeus Seneca]] was allowed to return to Rome, having been sent into exile by Claudius. <ref name=Scarre54>Scarre, Chris (1995). ''Chronicle of the Roman Emperis: The Reign-by-reign Record of the Rules of Imperial Rome''. London: Thames and Hudson. p. 54. ISBN 0-500-05077-5.</ref> | |||

On the advice of one of his freedmen, Claudius adopted Lucius as his son. This surprised many contemporaries as it was seen as a slight against his son, Britannicus. In recognition of his new status, on 25 February A.D. 50 Lucius officially became known as Tiberius Claudius Nero Caesar. Nero married Octavia, the daughter of the Emperor, in A.D. 53.<ref>Griffin, ''Nero: The End of a Dynasty'', pp. 29–30.</ref> To further enhance her son's claim as heir, Agrippina used her influence to have officers in the [[Praetorian Guard]] who she thought were loyal to Britannicus removed from their positions. She even chose the new Praetorian Prefect who commanded the guard, Sextus Africanus Burrus.<ref>Shotter, David (2008). ''Nero Caesar Augustus: Emperor of Rome''. Harlow: Pearson Educational Limited. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-4058-2457-6.</ref> | |||

==Roman Emperor (A.D. 54–68)== | |||

Nero was just 17 years old when Claudius died, and when the Praetorian Guard proclaimed him emperor he was the youngest man to have held the position.<ref>Le Glay, Marcel; Voisin, Jean-Louis; Le Bohec, Yann; Cherry, David & Kyle, Donald (2006). ''A History of Rome'', 3rd edition. Blackwell Publishing. pp. 234–235. ISBN 1-4051-1083-X</ref> It was the culmination of Agrippina's machinations to manoeuvre her son onto the throne, and there were rumours that she had conspired to have Claudius murdered. Recognising the importance of the Guard in supporting the Emperor, Nero gave each member 15,000 ''sestertii'' as Claudius had done 13 years earlier when he became Emperor.<ref>Shotter, ''Nero Caesar Augustus: Emperor of Rome'', pp. 53–54.</ref> A ''sestertius'' was a low denomination coin, and in the 1st century A.D. would have been enough to purchase four litres of wine.<ref>Greene, Kevin (1990). ''The Archaeology of the Roman Economy''. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. pp. 49, 52. ISBN 0-520-07401-7.</ref> | |||

As Claudius' son, Britannicus was the main threat to Nero's authority. He died in A.D. 55. The official explanation was that he died as the result of an [[epilepsy|epileptic fit]], though there has been speculation that Nero arranged for him to be murdered. While Britannicus was the only direct descendant of Claudius, there were other members of the imperial family with emperors in their lineage, making them potential rivals to Nero. [[Rubellius Plautus]] was the great grandson of the Emperor [[Tiberius]], while [[Faustus Sulla]] was married to [[Claudia Antonia]], Claudius' daughter by [[Aelia Paetina]]. Though neither man attempted to gain power Nero grew suspicious of them.<ref>Shotter, ''Nero Caesar Augustus: Emperor of Rome'', pp. 42–43.</ref> | |||

{{Image|Nero bust.jpg|thumb|250px|A bust of the Emperor Nero}} | |||

Shortly after becoming Emperor Nero began an affair with Acte, a [[freedwoman]] from the imperial household. Beginning in A.D. 55 the affair lasted several years.<ref>Griffin, ''Nero: The End of a Dynasty'', pp. 38–39.</ref> Nero's attention was also attracted by [[Poppaea Sabina]] who was married to [[Marcus Salvius Otho]], a friend of Nero's and himself a future Emperor.<ref>Shotter, ''Nero Caesar Augustus: Emperor of Rome'', p. 77.</ref> Otho was appointed governor of the province of Lusitania, and Poppaea remained in Rome, allowing Nero to begin an affair with her.<ref name=Scarre54/> In A.D. 62 Nero divorced Octavia. According to the historian [[Tacitus]], writing in the late 1st and early 2nd centuries, Nero accused his wife of committing [[adultery]] wife a slave. When Octavia's maid defended her mistress even under torture, Nero divorced Octavia claiming she was sterile. She was sent away from Rome and later murdered.<ref>Griffin, ''Nero: The End of a Dynasty'', p. 99.</ref> Once divorced, Nero married Poppaea Octavia died in exile the following year, her murder arranged by her former husband. Poppaea gave birth to a daughter, Claudia, on 21 January A.D. 63, though she died four months later.<ref name=Scarre54/> | |||

The [[Great Fire or Rome]] broke out on 19 July A.D. 64. It would become one of the most famous incidents from Nero's notorious reign, and rumours proliferated and it was suggested that the Emperor was responsible for the fire. He was in [[Antium]] when news of the fire reached him, and he immediately returned to Rome and arranged provisions for those rendered homeless. The city was badly damaged, particularly the centre and the imperial property. In the aftermath Nero began building the Golden Palace (''Domus Aurea''). A 125-hectare park was set out in the centre of Rome on some of the city's most expensive land, encompassing part of the Palatine and stretching from the [[Circus Maximus]] in the west to the Servian Walls (built in the 4th-century B.C.) enclosing the city in the east. Though never completed, the building caused consternation amongst Nero's contemporaries, and fuelled speculation that the Emperor had caused the fire to embark on his extravagant building programme. It did not help that Nero installed a 37-metre high statue of himself at a time when the imperial coffers were under considerable strain.<ref>Scarre, Chris (1995). ''Chronicle of the Roman Emperors'', pp. 53–55.</ref> | |||

Nero's spending was financed by increased taxes on the provinces of the empire, and in March A.D. 68 the governor of Gallia Lugdunensis, [[Julius Vindex]], led an uprising against Nero's rule. Demonstrating how unpopular Nero was, Vindex had the support of [[Servius Sulpicius Galba]], governor of Hispania Tarraconensis. The rebellion lasted until May that year, when it was suppressed by [[legion]]s which had been guarding the [[Rhine]] frontier.<ref>Scarre, Chris (1995). ''Chronicle of the Roman Emperors'', pp. 55–56.</ref> During the late 19th century and the first half of the 20th century there was a view that [[nationalism]] was the driving force behind Vindex's rebellion, however this was reassessed by later historians who felt that his motives were not nationalist in nature but derived from a feeling of mistreatment at the hands of Nero.<ref>Griffin, ''Nero: The End of a Dynasty'', p. 16.</ref> Such was the depth of feeling against Nero, however, that after the legions defeated Vindex they endorsed their leader as Emperor. While Verginius Rufus had no desire to be Emperor, Galba had agents in Rome were undermining Nero. The Emperor tried to escape Rome, but the Praetorian Guard would not allow him to leave. Nero escaped the city in disguise and hid a few miles from Rome. The Praetorian Guard however followed him to the villa. Before he could be arrested, Nero attempted to commit suicide. After Nero stabbed himself in the neck, his secretary made sure he was dead. Nero died on 9 June A.D. 68 and was succeeded by Galba. | |||

==Legacy and historiography== | |||

Most of the surviving ancient literature relating to Nero was written after his death, and relied on earlier sources which no longer survive. There are three main sources for Nero's life and reign: [[Tacitus]], [[Suetonius]], and [[Dio Cassius]]. Tacitus was the earliest of these, and was just 11 when Nero died, while both Suetonius and Dio Cassius were born after A.D. 68 (in the case of the latter, nearly a century later).<ref>Shotter, ''Nero Caesar Augustus: Emperor of Rome'', p. 2.</ref> | |||

The surviving literature from the Roman world is united in the opinion that Nero was a tyrant. For instance [[Pliny the Elder]] wrote that Nero was "the destroyer of the human race". For later historians, Italian in particular, he was considered the archetypal despot along with figures such as Caligula. In Christian writings Nero was considered the [[Anti-Christ]], an opinion which gained popularity as Christianity became a mainstream religion. Nero's notoriety persisted over the following centuries (he was reference in the play ''[[Hamlet]]''), and amongst modern historians it is considered that Nero's personality contributed to the rebellion which led to his downfall.<ref>Griffin, ''Nero: The End of a Dynasty'', pp. 15–16.</ref> | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

{{reflist}} | {{reflist}}[[Category:Suggestion Bot Tag]] | ||

Latest revision as of 16:01, 24 September 2024

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus, commonly referred to as Nero, was Roman Emperor from A.D. 54 to A.D. 68. His mother married the Emperor Claudius in A.D. 49 and the following year the Emperor adopted Nero as his son. On Claudius' death in A.D. 54 Nero was proclaimed Emperor by the Praetorian Guard, becoming the youngest Roman Emperor in history. His mother was influential in ensuring Nero succeeded Claudius, though he later had her murdered.

One of the most famous events of Nero's reign was the Great Fire of Rome in A.D. 64. The city was devastated by the fire, and in the aftermath Nero cleared some of the damaged areas to built his Golden Palace. The expensive building was unpopular at the time, and there was speculation that Nero had arranged the fire himself so he could construct the palace. Nero was unpopular amongst the upper classes, and a rebellion in A.D. 68 led to the end of Nero's reign, and on 9 June he committed suicide by stabbing himself in the neck. He was succeeded by Servius Sulpicius Galba who had joined the rebellion against him.

Early life (A.D. 37–54)

Nero was born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus in A.D. 37, during the reign of Caligula; he was the son of Julia Agrippina and Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus. Julia's father, Germanicus Caesar, had been adopted by the Emperor Tiberius and the people of Rome felt that the family were the heirs of Augustus, who had himself adopted Tiberius. Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus died in A.D. 39 and Agrippina was exiled the same year, taking her son with her. When Claudius became Emperor in A.D. 41 he recalled Agrippina and Lucius to Rome.[2] Claudius' wife, Messallina, began an affair and with her lover plotted to assassinate the Emperor. The plan was discovered in A.D. 48 and Messallina committed suicide, leaving behind two children from her marriage to Claudius: a girl, Octavia, and a boy, Britannicus. The following year Agrippina married Claudius, who was her uncle.[3] In A.D. 49 the philosopher Lucius Annaeus Seneca was allowed to return to Rome, having been sent into exile by Claudius. [4]

On the advice of one of his freedmen, Claudius adopted Lucius as his son. This surprised many contemporaries as it was seen as a slight against his son, Britannicus. In recognition of his new status, on 25 February A.D. 50 Lucius officially became known as Tiberius Claudius Nero Caesar. Nero married Octavia, the daughter of the Emperor, in A.D. 53.[5] To further enhance her son's claim as heir, Agrippina used her influence to have officers in the Praetorian Guard who she thought were loyal to Britannicus removed from their positions. She even chose the new Praetorian Prefect who commanded the guard, Sextus Africanus Burrus.[6]

Roman Emperor (A.D. 54–68)

Nero was just 17 years old when Claudius died, and when the Praetorian Guard proclaimed him emperor he was the youngest man to have held the position.[7] It was the culmination of Agrippina's machinations to manoeuvre her son onto the throne, and there were rumours that she had conspired to have Claudius murdered. Recognising the importance of the Guard in supporting the Emperor, Nero gave each member 15,000 sestertii as Claudius had done 13 years earlier when he became Emperor.[8] A sestertius was a low denomination coin, and in the 1st century A.D. would have been enough to purchase four litres of wine.[9]

As Claudius' son, Britannicus was the main threat to Nero's authority. He died in A.D. 55. The official explanation was that he died as the result of an epileptic fit, though there has been speculation that Nero arranged for him to be murdered. While Britannicus was the only direct descendant of Claudius, there were other members of the imperial family with emperors in their lineage, making them potential rivals to Nero. Rubellius Plautus was the great grandson of the Emperor Tiberius, while Faustus Sulla was married to Claudia Antonia, Claudius' daughter by Aelia Paetina. Though neither man attempted to gain power Nero grew suspicious of them.[10]

Shortly after becoming Emperor Nero began an affair with Acte, a freedwoman from the imperial household. Beginning in A.D. 55 the affair lasted several years.[11] Nero's attention was also attracted by Poppaea Sabina who was married to Marcus Salvius Otho, a friend of Nero's and himself a future Emperor.[12] Otho was appointed governor of the province of Lusitania, and Poppaea remained in Rome, allowing Nero to begin an affair with her.[4] In A.D. 62 Nero divorced Octavia. According to the historian Tacitus, writing in the late 1st and early 2nd centuries, Nero accused his wife of committing adultery wife a slave. When Octavia's maid defended her mistress even under torture, Nero divorced Octavia claiming she was sterile. She was sent away from Rome and later murdered.[13] Once divorced, Nero married Poppaea Octavia died in exile the following year, her murder arranged by her former husband. Poppaea gave birth to a daughter, Claudia, on 21 January A.D. 63, though she died four months later.[4]

The Great Fire or Rome broke out on 19 July A.D. 64. It would become one of the most famous incidents from Nero's notorious reign, and rumours proliferated and it was suggested that the Emperor was responsible for the fire. He was in Antium when news of the fire reached him, and he immediately returned to Rome and arranged provisions for those rendered homeless. The city was badly damaged, particularly the centre and the imperial property. In the aftermath Nero began building the Golden Palace (Domus Aurea). A 125-hectare park was set out in the centre of Rome on some of the city's most expensive land, encompassing part of the Palatine and stretching from the Circus Maximus in the west to the Servian Walls (built in the 4th-century B.C.) enclosing the city in the east. Though never completed, the building caused consternation amongst Nero's contemporaries, and fuelled speculation that the Emperor had caused the fire to embark on his extravagant building programme. It did not help that Nero installed a 37-metre high statue of himself at a time when the imperial coffers were under considerable strain.[14]

Nero's spending was financed by increased taxes on the provinces of the empire, and in March A.D. 68 the governor of Gallia Lugdunensis, Julius Vindex, led an uprising against Nero's rule. Demonstrating how unpopular Nero was, Vindex had the support of Servius Sulpicius Galba, governor of Hispania Tarraconensis. The rebellion lasted until May that year, when it was suppressed by legions which had been guarding the Rhine frontier.[15] During the late 19th century and the first half of the 20th century there was a view that nationalism was the driving force behind Vindex's rebellion, however this was reassessed by later historians who felt that his motives were not nationalist in nature but derived from a feeling of mistreatment at the hands of Nero.[16] Such was the depth of feeling against Nero, however, that after the legions defeated Vindex they endorsed their leader as Emperor. While Verginius Rufus had no desire to be Emperor, Galba had agents in Rome were undermining Nero. The Emperor tried to escape Rome, but the Praetorian Guard would not allow him to leave. Nero escaped the city in disguise and hid a few miles from Rome. The Praetorian Guard however followed him to the villa. Before he could be arrested, Nero attempted to commit suicide. After Nero stabbed himself in the neck, his secretary made sure he was dead. Nero died on 9 June A.D. 68 and was succeeded by Galba.

Legacy and historiography

Most of the surviving ancient literature relating to Nero was written after his death, and relied on earlier sources which no longer survive. There are three main sources for Nero's life and reign: Tacitus, Suetonius, and Dio Cassius. Tacitus was the earliest of these, and was just 11 when Nero died, while both Suetonius and Dio Cassius were born after A.D. 68 (in the case of the latter, nearly a century later).[17]

The surviving literature from the Roman world is united in the opinion that Nero was a tyrant. For instance Pliny the Elder wrote that Nero was "the destroyer of the human race". For later historians, Italian in particular, he was considered the archetypal despot along with figures such as Caligula. In Christian writings Nero was considered the Anti-Christ, an opinion which gained popularity as Christianity became a mainstream religion. Nero's notoriety persisted over the following centuries (he was reference in the play Hamlet), and amongst modern historians it is considered that Nero's personality contributed to the rebellion which led to his downfall.[18]

References

- ↑ Griffin, Miriam T. (1987). Nero: The End of a Dynasty. London: Routledge. p. 121. ISBN 978-0415214643.

- ↑ Shotter, David (2005). Nero, 2nd edition. London: Routledge. pp. 10–11. ISBN 0-415-31941-2.

- ↑ Griffin, Nero: The End of a Dynasty, pp. 28–29.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Scarre, Chris (1995). Chronicle of the Roman Emperis: The Reign-by-reign Record of the Rules of Imperial Rome. London: Thames and Hudson. p. 54. ISBN 0-500-05077-5.

- ↑ Griffin, Nero: The End of a Dynasty, pp. 29–30.

- ↑ Shotter, David (2008). Nero Caesar Augustus: Emperor of Rome. Harlow: Pearson Educational Limited. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-4058-2457-6.

- ↑ Le Glay, Marcel; Voisin, Jean-Louis; Le Bohec, Yann; Cherry, David & Kyle, Donald (2006). A History of Rome, 3rd edition. Blackwell Publishing. pp. 234–235. ISBN 1-4051-1083-X

- ↑ Shotter, Nero Caesar Augustus: Emperor of Rome, pp. 53–54.

- ↑ Greene, Kevin (1990). The Archaeology of the Roman Economy. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. pp. 49, 52. ISBN 0-520-07401-7.

- ↑ Shotter, Nero Caesar Augustus: Emperor of Rome, pp. 42–43.

- ↑ Griffin, Nero: The End of a Dynasty, pp. 38–39.

- ↑ Shotter, Nero Caesar Augustus: Emperor of Rome, p. 77.

- ↑ Griffin, Nero: The End of a Dynasty, p. 99.

- ↑ Scarre, Chris (1995). Chronicle of the Roman Emperors, pp. 53–55.

- ↑ Scarre, Chris (1995). Chronicle of the Roman Emperors, pp. 55–56.

- ↑ Griffin, Nero: The End of a Dynasty, p. 16.

- ↑ Shotter, Nero Caesar Augustus: Emperor of Rome, p. 2.

- ↑ Griffin, Nero: The End of a Dynasty, pp. 15–16.