History of Pittsburgh: Difference between revisions

imported>Richard Jensen (→External links: add bibliog) |

imported>Richard Jensen (→Bibliography: add) |

||

| Line 324: | Line 324: | ||

* Krause, Paul. ''The Battle for Homestead, 1880-1892: Politics, Culture, and Steel.'' U. of Pittsburgh Press, 1992. 548 pp. | * Krause, Paul. ''The Battle for Homestead, 1880-1892: Politics, Culture, and Steel.'' U. of Pittsburgh Press, 1992. 548 pp. | ||

* Lopez, Steven Henry. ''Reorganizing the Rust Belt: An Inside Study of the American Labor Movement.'' U. of California Press, 2004. 314 pp. | * Lopez, Steven Henry. ''Reorganizing the Rust Belt: An Inside Study of the American Labor Movement.'' U. of California Press, 2004. 314 pp. | ||

* Lorant, Stefan. ''Pittsburgh: The Story of an American City,'' (1964), well written, heavily illustrated popular history | |||

* Lubove, Roy. ''Twentieth Century Pittsburgh: Government, Business, and Environmental Change'' (1969) | |||

* Lubove, Roy. ''Twentieth-Century Pittsburgh. Vol. 2: The Post-Steel Era.'' U. of Pittsburgh Press, 1996. 413 pp. the major scholarly synthesis | * Lubove, Roy. ''Twentieth-Century Pittsburgh. Vol. 2: The Post-Steel Era.'' U. of Pittsburgh Press, 1996. 413 pp. the major scholarly synthesis | ||

* David Nasaw, ''Andrew Carnegie'' (2006) | * David Nasaw, ''Andrew Carnegie'' (2006) | ||

| Line 335: | Line 338: | ||

* Tarr, Joel A., ed. ''Devastation and Renewal: An Environmental History of Pittsburgh and Its Region.'' U. of Pittsburgh Press, 2003. 312 pp. [http://www.h-net.msu.edu/reviews/showrev.cgi?path=128511093889206 online review] | * Tarr, Joel A., ed. ''Devastation and Renewal: An Environmental History of Pittsburgh and Its Region.'' U. of Pittsburgh Press, 2003. 312 pp. [http://www.h-net.msu.edu/reviews/showrev.cgi?path=128511093889206 online review] | ||

* Wade, Richard C. ''The Urban Frontier: The Rise of Western Cities, 1790-1830.'' (1959) | * Wade, Richard C. ''The Urban Frontier: The Rise of Western Cities, 1790-1830.'' (1959) | ||

* Wall, Joseph. ''Carnegie'' | * Wall, Joseph. ''Andrew Carnegie'' (1970). 1137 pp. | ||

* Weber, Michael P. ''Don't Call Me Boss: David L. Lawrence, Pittsburgh's Renaissance Mayor.'' U. of Pittsburgh Press, 1988. 440 pp. | * Weber, Michael P. ''Don't Call Me Boss: David L. Lawrence, Pittsburgh's Renaissance Mayor.'' U. of Pittsburgh Press, 1988. 440 pp. | ||

===Primary sources=== | |||

* Lubove, Roy, ed. ''Pittsburgh'' 1976. 294 pp. short excerpts | |||

== External links == | == External links == | ||

Revision as of 20:08, 3 April 2007

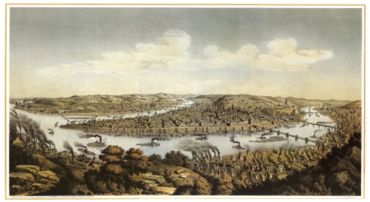

The site of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, United States, is at the confluence of the Allegheny River and the Monongahela River, forming the Ohio River. The history of Pittsburgh began with a struggle between Native Americans, the French and the British over the control of this strategic juncture[2][1] Native Americans had populated this region for more than 10,000 years.[3] In 1754, to enforce their territorial claims, the French built Fort Duquesne at the Ohio's head. This triggered the French and Indian War.[4] After British General John Forbes occupied Fort Duquesne, he ordered the construction of Fort Pitt. He named the settlement between the rivers "Pittsborough."[5] During Pontiac's Rebellion, Ohio Valley and Great Lakes tribes besieged Fort Pitt for two months, [1] but their siege was lifted.[2]

Following the American Revolution, the village around the fort continued to grow. One of its earliest industries was building boats for settlers to enter the Ohio Country. The year 1794 saw the short-lived Whiskey Rebellion, when farmers rebelled against federal taxes on whiskey. The War of 1812 cut off the supply of British goods, stimulating American manufacture. By 1815, Pittsburgh was producing significant quantities of iron, brass, tin and glass products. By the 1840s, Pittsburgh had grown to one of the largest cities west of the Allegheny Mountains. A great fire burned more than a thousand buildings in 1845, but the city rebuilt. By 1857, Pittsburgh had nearly 1,000 factories. The American Civil War boosted the city's economy still further, with increased production of iron and armaments. Production of steel began in 1875. By 1911, Pittsburgh was producing as much as half of the nation's steel. In the early 20th century, the city's population topped half a million, including many European immigrants. During World War II, Pittsburgh contributed more than 95 million tons of steel to the allied war effort.[5]

Following World War II, the city launched a clean air and civic revitalization project known as the "Renaissance." The industrial base continued to expand through the 1960s. In the 1980s, however, the steel industry imploded, with massive layoffs and mill closures. Pittsburgh shifted its economic base to higher education, services, tourism, medicine and high technology. During this transition, the city population shrank to 330,000.

Native American era

For thousands of years, Native Americans inhabited the region where the Allegheny and the Monongahela join to form the Ohio. Paleo-Indians conducted a hunter-gatherer lifestyle perhaps as early as 19,000 years ago.[3] Meadowcroft Rockshelter, west of Pittsburgh, provides evidence that these first Americans occupied the region from that early date.

During the Adena culture, Mound Builders erected a large Indian Mound at McKees Rocks, about three miles from the head of the Ohio. The Indian Mound, a burial site, was augmented in later years by members of the Hopewell culture.[6]

European diseases, such as smallpox, measles, influenza, and malaria, preceded European explorers to western Pennsylvania, devastating the populations of the Native Americans living there.[7]

In the early 18th century, the Iroquois held dominion over the upper Ohio valley from their homelands in present-day New York State. Other Native American tribes in the upper Ohio valley included the Lenape, or Delawares, who had been displaced from eastern Pennsylvania by European settlement, and the Shawnees, who had migrated up from the south.[8]

In 1748, when Conrad Weiser visited Logstown, he counted 789 warriors from ten different tribes:[9]

- Iroquois, or Six Nation:

- Allies of Iroquois:

- Wyandots: 100

- Others:

- Shawnees: 162

- Tisagechroamis: 40

- Mohicans: 15

- Lenape (Delaware): 165

- Total : 789

Shannopin's Town, a Seneca tribe village on the east bank of the Allegheny, was the home village of Queen Aliquippa, but was gone after 1749. Chartier's Town was a Shawnee town. Sawcunk, on the mouth of the Beaver River, was a Lenape (Delaware) settlement and the principal residence of Shingas, a chief of the Lenapes.[10] Kittanning was a Lenape and Shawnee village on the Allegheny with an estimated 300–400 residents.[11]

Struggle for Control of the Forks of the Ohio (1747–1763)

In 1748, the first Ohio Company won a grant of 200,000 acres in the upper Ohio valley. From a post at present-day Cumberland, Maryland, the company began to construct an 80-mile wagon road to the Monongahela River.[5]

The French had built Logstown for the Native Americans as a trade and council center, in order to increase their influence in the Ohio valley.[9] Between 1749-06-15 and 1749-11-10, to bolster the French claim to the region, an expedition headed by Celeron de Bienville traveled down the Allegheny and Ohio. De Bienville warned away English traders and posted markers claiming the territory.[12]

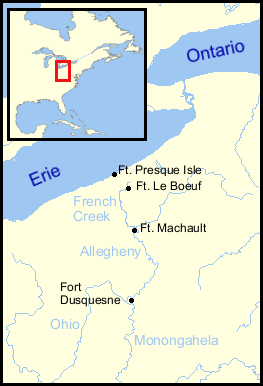

In 1753, Marquis Duquesne, the Governor of New France, sent another, larger expedition. At present-day Erie, Pennsylvania, an advance party built Fort Presque Isle. They also cut a road through the woods and built Fort Le Boeuf on French Creek, from which it was possible at high water to float to the Allegheny. By summer, an expedition of 1,500 French and Native American men descended the Allegheny. Some wintered at the confluence of French Creek and the Allegheny, where, the following year, they built Fort Machault.[13]

Alarmed at these French incursions in the Ohio valley, Governor Dinwiddie of Virginia sent Major George Washington to warn the French to withdraw.[1] Accompanied by Christopher Gist, Washington arrived at the Forks of the Ohio on 1753-11-25, recording his impressions in his journal:[14]

"As I got down before the Canoe, I spent some Time in viewing the Rivers, & the Land in the Fork, which I think extreamly well situated for a Fort; as it has the absolute Command of both Rivers. The Land at the Point is 20 or 25 feet above the common Surface of the Water; & a considerable Bottom of flat well timber'd Land all around it, very convenient for Building."

Proceeding up the Allegheny, Washington presented Dinwiddie's letter to the French commanders first at Venango, and then Fort Le Boeuf. The French officers received Washington with wine and courtesy, but did not withdraw.

Governor Dinwiddie then sent Captain William Trent to build a fort at the Forks of the Ohio. On 1754-02-17 Trent began construction of the fort, the first European habitation[15] at the site of present-day Pittsburgh. The fort, named Fort Prince George, was only half-built by April 1754, when over 500 French forces arrived and ordered the 40-some colonials back to Virginia. The French then tore down the British effort and built Fort Duquesne.[13][1]

Governor Dinwiddie launched another expedition. Colonel Joshua Fry commanded the regiment. His second-in-command, George Washington, led an advance column. On 1754-05-28, Washington's unit clashed with the French in the Battle of Jumonville Glen. After the battle, Washington's ally, Seneca chief Tanaghrisson, tomahawked a prisoner, Ensign Joseph Coulon de Jumonville. On 1754-07-03, George Washington surrendered following the Battle of Fort Necessity. These actions sparked the French and Indian War (1754–1763), or, the Seven Years' War, an imperial confrontation between England and France fought in both hemispheres.[4][1]

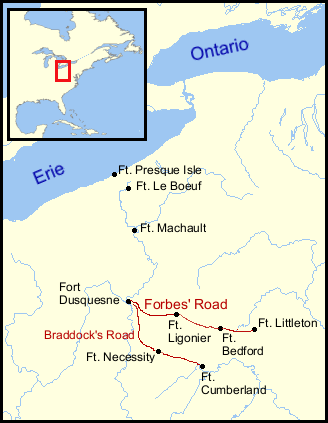

In 1755, George Washington accompanied British General Braddock's expedition. Two regiments marched from Fort Cumberland. Following a path Washington surveyed, over 3,000 men built a wagon road 12-feet wide. When complete, Braddock's Road was the first road to cross the Appalachian Mountains. It blazed the way for the future National Road. The expedition crossed the Monongahela River on July 9 1755. French troops from Fort Duquesne ambushed Braddock's expedition at Braddock's Field, nine miles from Fort Duquesne.[16] In the Battle of the Monongahela, the French inflicted heavy losses on the British. Braddock was mortally wounded.[2] The surviving British and colonial forces retreated. This left the French and their Native American allies with dominion over the upper Ohio valley.[1]

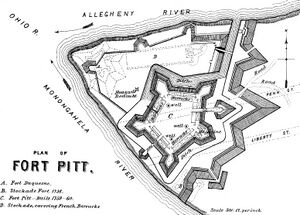

On 8 September 1756, an expedition of 300 militiamen destroyed the Shawnee and Lenape village of Kittanning. In the summer of 1758, British General John Forbes began a campaign to capture Fort Duquesne.[2] At the head of 7,000 regular and colonial troops, Forbes built Fort Ligonier and Fort Bedford, from where he cut a wagon road over the Allegheny Mountains, later known as Forbes’ Road. On the night of Sept. 13–14, 1758, an advance column under Major James Grant was massacred in the Battle of Fort Duquesne.[2] The battleground, the high hill east of the Point, was named Grant's Hill in the memory of Major Grant. With this defeat, Forbes decided to wait until spring. But when he heard that the French had lost Fort Frontenac and largely evacuated Fort Duquesne, he planned an immediate attack. Now hopelessly outnumbered, the French abandoned and razed Fort Duquesne. Forbes occupied the burned fort on November 25 1758. He ordered the construction of Fort Pitt, named after British Secretary of State William Pitt the Elder. He also named the settlement between the rivers, "Pittsborough."[5][1] The British garrison at Fort Pitt made substantial improvements to its fortification.[5] The French never attacked Fort Pitt.[1] The French and Indian War ended with the Treaty of Paris (1763).

Gateway to the West (1763–1799)

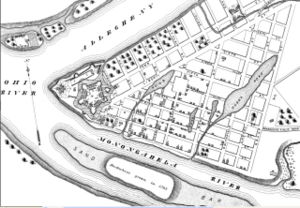

In 1760, the first considerable settlement around Fort Pitt began to grow.[2] Traders and settlers built two groups of houses and cabins, the "lower town," near the fort's ramparts, and the "upper town," along the Monongahela as far as present-day Market Street.[2] In April 1761, a census ordered by Colonel Henry Bouquet counted 332 people and 104 houses.[2]

In a final attempt to drive out the British, Pontiac's Rebellion began with an assault on British forts in May 1763. Ohio Valley and Great Lakes tribes overran many forts; one of their most important targets was Fort Pitt. Receiving warning of the coming attack, Captain Simeon Ecuyer, the Swiss officer in command of the garrison, prepared for a siege. He leveled the houses outside the ramparts and ordered all settlers into the fort: 330 men, 104 women and 196 children sought refuge inside its ramparts.[5] Captain Ecuyer also gathered stores, to include hundreds of barrels of pork and beef. Pontiac's forces attacked the fort on 22 June, 1763. The siege of Fort Pitt lasted for two months.[1] Pontiac's warriors kept up a continuous, though ineffective, fire on it from 27 July through 1 August, 1763.[2] Then they drew off to meet the relieving party under Colonel Bouquet, which defeated them in the Battle of Bushy Run.[2] This victory sealed British dominion over the forks of the Ohio, if not the entire Ohio valley. In 1764 Colonel Bouquet added a redoubt, the "Block House," which still stands, the sole remaining structure from Fort Pitt and the oldest authenticated building west of the Allegheny Mountains.[1]

The Iroquois signed the Fort Stanwix Treaty of 1768, ceding the lands south of the Ohio to the British.[2] European expansion into the upper Ohio valley increased. An estimated 4,000 to 5,000 families settled in western Pennsylvania between 1768 and 1770.[17] Of these settlers, about a third were English, a third were Scotch-Irish and the rest were Welsh, German and others.[17] These groups tended to settle together in small farming communities, but often their households were not within hailing distance. The life of a settler family was one of relentless hard work: clearing the forest, stumping the fields, building cabins and barns, planting, weeding and harvesting. In addition, almost everything had to be manufactured by hand, including furniture, tools, candles, buttons and needles.[17] Settlers had to deal with harsh winters, and with snakes, black bears, mountain lions and timber wolves. Because of the fear of raids by Native Americans, the settlers often built their cabins near, or even on top of, springs. They also built blockhouses, where neighbors would rally during conflicts.[8]

Increasing violence with especially the Shawnee, Miami, and Wyandot tribes lead to Dunmore's War in 1774, and conflict with Native Americans continued throughout the American Revolution. In 1777, Fort Pitt became a United States fort, when Brigadier General Edward Hand took command. In 1779, Colonel Daniel Brodhead led 600 men from Fort Pitt to destroy Seneca villages along the upper Allegheny.[8]

With the war still on-going, in 1780 Virginia and Pennsylvania came to an agreement on their mutual borders, creating the state lines known today and determining finally that the Pittsburgh region was Pennsylvanian. In 1783, the Revolutionary War ended, which also brought at least a temporary cessation of border warfare. In the 1784 Treaty of Fort Stanwix, the Iroquois ceded the land north of the Purchase Line to Pennsylvania.

After the Revolution, the village of Pittsburgh continued to grow. One of its earliest industries was boat building. With its strategic location at the mouth of the Ohio, and plentiful timber close by, Pittsburgh was well-situated for the building of flatboats, used by settlers to reach the Ohio country, and for farmers to send their products down river, sometimes as far as New Orleans. Often these boats would be broken up at their destination and used for construction materials. Prior to steam power, the up-river journey, by poling, rowing and pulling, was slow and expensive, but long, narrow keelboats were built for the purpose.

The village began to develop vital institutions. Hugh Henry Brackenridge, a Pittsburgh resident and state legislator, introduced a bill that resulted in a gift deed of land and a charter for the Pittsburgh Academy in February 28 1787. The Academy later became the University of Western Pennsylvania (1819) and the University of Pittsburgh (1908). [19]

Many farmers distilled their corn harvest into whiskey, increasing its value while lowering its transportation costs. When the federal government imposed an excise tax on whiskey, farmers felt victimized, leading to the Whiskey Rebellion in 1794. Farmers from the region rallied at Braddock's Field and marched on Pittsburgh.[16] The short-lived rebellion was put down, however, when President George Washington sent in militias from several states.

The town continued to grow in manufacturing capability. In 1792, the boatyards in Pittsburgh built a sloop, Western Experiment.[20] During the next decades, the yards produced other large boats. By the 1800s, they were building ocean-going vessels that shipped goods as far as Europe. In 1794, the town's first courthouse, a wooden structure on Market Square, was built.[5] In 1797, the manufacture of glass began.[21]

| Year | City Population |

|---|---|

| 1761 | 332 |

| 1796 | 1,300 |

| 1800 | 1,565 |

The Iron City (1800–1859)

Commerce continued to be an essential part of the economy of early Pittsburgh, but increasingly, manufacture began to grow in importance. Pittsburgh sat in the middle of one of the most productive coalfields in the country; the region was also rich in petroleum, natural gas, lumber and farm goods. Also, the early settlers were accustomed to manufacturing everything they needed. Blacksmiths forged iron implements, from horse shoes to nails. By 1800, the town, with a population of 1,565 persons, had over 60 shops, including general stores, bakeries, and hat and shoe shops.[5]

The 1810s were a critical decade in Pittsburgh's growth. In 1811, the first steamboat was built in Pittsburgh. Increasingly, commerce would also flow upriver. The War of 1812 was catalytic in the growth of the Iron City. The war with Britain, the manufacturing center of the world, cut off the supply of British goods, stimulating American manufacture.[5] Also, the British blockade of the American coast increased inland trade, so that goods flowed through Pittsburgh from all four directions. By 1815, Pittsburgh was producing $764K in iron; $249K in brass and tin, and $235K in glass products.[5] When, on March 18, 1816, Pittsburgh was incorporated as a city, it had already taken on some of its defining characteristics: commerce, manufacture, and a constant cloud of coal dust.[23] With a population of 6,000, Pittsburgh was already Pittsburgh.

Other emerging towns challenged Pittsburgh. In 1818, the first segment of the National Road was completed, from Baltimore to Wheeling, bypassing Pittsburgh. This threatened to render the town less essential in east-west commerce. In the coming decade, however, many improvements were made to the transportation infrastructure. In 1818, the region's first river bridge, the Smithfield Street Bridge, opened, the first step in building the city of bridges.[24] In 1820, the original Pennsylvania Turnpike was completed, connecting Pittsburgh and Philadelphia. In 1829, the Pennsylvania Main Line Canal began operations.[21] Now Pittsburgh was part of a transportation system that included rivers, roads and canals.

Manufacture continued to grow. In 1835, McClurg, Wade and Co. built the first locomotive west of the Alleghenies. Already, Pittsburgh was capable of manufacturing the most essential machines of its age. By the 1840s, Pittsburgh was not a town, but one of the largest cities west of the mountains. In 1841, the Second Court House, on Grant's Hill, was completed. Made from polished gray sandstone, the court house had a rotunda 60 feet in diameter and 80 feet high.[25]

Like many burgeoning cities of its day, Pittsburgh's growth outstripped some of its necessary infrastructure, such as a water supply with dependable pressure.[26] Because of this, on April 10 1845, a great fire burned out of control, destroying over a thousand buildings and causing $9M in damages.[22] As the city rebuilt, the age of rails arrived. In 1851, the Ohio and Pennsylvania Railroad began service between Cleveland and Allegheny City (present-day North Side).[21] In 1854, the Pennsylvania Railroad began service between Pittsburgh and Philadelphia.

Despite many challenges, Pittsburgh had grown into an industrial powerhouse. An 1857 article[22] provided a snapshot of the Iron City:

- 939 factories in Pittsburgh and Allegheny City

- employing more than 10 K workers

- producing almost $12M in goods

- using 400 steam engines

- Total coal consumed - 22M bushels

- Total iron consumed - 127 K tons

- In steam tonnage, third busiest port in the nation, surpassed only by New York City and New Orleans.

| Year | City Population | City Rank [1] |

|---|---|---|

| 1800 | 1,565 | NA |

| 1810 | 4,768 | 31 |

| 1820 | 7,248 | 23 |

| 1830 | 12,568 | 17 |

| 1840 | 21,115 | 17 |

| 1850 | 46,601 | 13 |

| 1860 | 49,221 | 17 |

The Steel City (1859–1946)

During the mid-1800s, Pittsburgh witnessed a dramatic influx of German immigrants, including a brick mason whose son, Henry J. Heinz, founded the H.J. Heinz Company in 1872. Heinz was at the forefront of reform efforts to improve food purity, working conditions, hours and wages.[28]

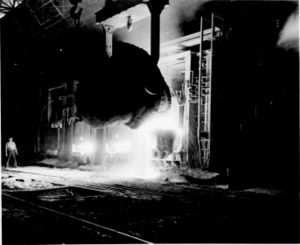

The iron industry in Pittsburgh was thriving. In 1859, the Clinton and Soho iron furnaces introduced coke-fire smelting to the region. The American Civil War boosted the city's economy with increased production of iron and armaments, especially at the Allegheny Arsenal and the Fort Pitt Foundry.[25] Arms manufacture included iron-clad warships and the world's first 21" gun.[29] By war's end, over one-half of the steel and more than one-third of all U.S. glass was produced in Pittsburgh.[28] A milestone in steel production was achieved in 1875, when the Edgar Thomson Works in Braddock began to make steel rail using the new Bessemer process.

Industrialists such as Andrew Carnegie, Henry Clay Frick, Andrew W. Mellon, and Charles M. Schwab built their fortunes here. George Westinghouse, credited with such advancements as the air brake and alternating current, founded over 60 companies in Pittsburgh, including Westinghouse Air and Brake Company (1869), Union Switch & Signal (1883), and Westinghouse Electric Company (1886). Banks played a key role in Pittsburgh's development as these industrialists sought massive loans to upgrade plants, integrate industries and fund technological advances. For example, T. Mellon & Sons Bank, founded in 1869, helped finance an aluminum reduction company that became Alcoa.[28]

As a manufacturing center, Pittsburgh also became an arena for intense labor strife. During the great railroad strike of 1877, Pittsburgh erupted into widespread rioting.[30] Dozens died and over 40 buildings were burned down, including the Union Depot of the Pennsylvania Railroad. Fifteen years later, in 1892, another tragic episode in labor relations resulted in 10 deaths when Carnegie Steel Company's manager Henry Clay Frick sent in Pinkertons to break the Homestead Strike.

Andrew Carnegie, a former Pennsylvania Railroad executive turned steel magnate, founded the Carnegie Steel Company. He proceeded to play a key role in the development of the U.S. steel industry. In 1890, he established the first Carnegie Library, and in 1895, the Carnegie Institute. In 1901, as the U.S. Steel Corporation formed, he sold his mills to J.P. Morgan for $250 million, making him one of the world's richest men. Carnegie once wrote that a man who dies rich, dies disgraced.[31] He devoted the rest of his life to public service, establishing libraries, trusts and foundations. In Pittsburgh, he founded the Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University) and the Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh.[28]

In civic developments, in 1886, the third (and present) Allegheny County Courthouse and Jail was completed. In 1890, trolleys began operations. In 1907, the city had a major flood.[21] Pittsburgh annexed Allegheny City.[21]

By 1911, Pittsburgh had grown into an industrial and commercial powerhouse:[2]

- Nexus of a vast railway system, with freight yards capable of handling 60 K cars

- 27.2 miles of harbor

- Yearly river traffic in excess of 9M tons

- Value of factory products more than $211M (with Allegheny City)

- Allegheny county produced, as percentage of national output, about:

- 24% of the pig-iron

- 34% of the Bessemer steel

- 44% of the open-hearth steel

- 53% of the crucible steel

- 24% of the steel rails

- 59% of the structural shapes

To escape the soot of the city, many of the wealthy lived in the Shadyside and East End neighborhoods, a few miles east of downtown. Fifth Avenue was dubbed "Millionaire's Row" because of the many mansions lining the street. Oakland became the city's predominant cultural and educational center, including four universities, multiple museums, a library, a music hall and a botanical conservatory. Oakland's University of Pittsburgh erected the world's second-tallest educational building, the 42-story Cathedral of Learning.[33] It towered over Forbes Field, where the Pittsburgh Pirates played from 1909–1970.[28]

Between 1870 and 1920, the population of Pittsburgh grew almost sevenfold. Many of the new residents were immigrants who sought employment in the factories and mills and introduced new traditions, languages and cultures to the city. Ethnic neighborhoods emerged on densely populated hillsides and valleys, such as Polish Hill, Bloomfield and Squirrel Hill, home to 28% of the city's almost 21,000 Jewish households.[34] The Strip District, the city's produce distribution center, still boasts many restaurants and clubs that showcase these multicultural traditions of Pittsburghers.[28]

The years 1916–1930 marked the largest migration of African-Americans to Pittsburgh. Known as the cultural nucleus of Black Pittsburgh, Wylie Avenue in the Hill District was an important jazz mecca. Jazz greats such as Duke Ellington and Pittsburgh natives Billy Strayhorn and Earl Hines played here. Two of the Negro League's greatest rivals, the Pittsburgh Crawfords and the Homestead Grays, often competed in the Hill District. The teams dominated the Negro National League in the 1930s and 1940s.[28]

During World War II, Pittsburgh's mills contributed 95 million tons of steel to the Allied war effort.[5]

| Year | City Population | City Rank [2] |

|---|---|---|

| 1860 | 49,221 | 17 |

| 1870 | 86,076 | 16 |

| 1880 | 156,389 | 12 |

| 1890 | 238,617 | 13 |

| 1900 | 321,616 | 11 |

| 1910 | 533,905 | 8 |

| 1920 | 588,343 | 9 |

| 1930 | 669,817 | 10 |

| 1940 | 671,659 | 10 |

| 1950 | 676,806 | 12 |

Renaissance I (1946–1973)

Rich and productive, Pittsburgh was also the "Smoky City," with smog sometimes so thick that streetlights burned during the day.[5] Civic leaders, notably Mayor David L. Lawrence, elected in 1945, and Richard K. Mellon, chairman of Mellon Bank, began smoke control and urban revitalization projects that transformed the city.[5] Renaissance I began in 1946. By 1950, the first building project, the Gateway Center, was under construction. 1953 saw the opening of the (since demolished) Greater Pittsburgh Municipal Airport.[21] Ninety-five acres of the lower Hill District were cleared, displacing 1,200 residents, most of them African-American, in order to make room for the Civic Arena, which opened in 1961.[35]

The city's industrial base continued to grow. Jones and Laughlin Steel Company expanded its plant on the Southside. H.J. Heinz, Pittsburgh Plate Glass, Alcoa, Westinghouse, U.S. Steel and its new division, the Pittsburgh Chemical Company and many other companies also continued robust operations through the 1960s.[5] 1970 marked the completion of the final building projects of Renaissance I, the U.S. Steel Tower and Three Rivers Stadium.[21] In 1974, with the addition of the fountain at the tip of the Golden Triangle, Point State Park was completed.[36] The city was revitalized. Air quality was dramatically improved. Pittsburgh's manufacturing base seemed solid. Pittsburgh, however, was about to undergo one of its most dramatic transformations.

Reinvention (1973–present)

During the 1970s and 1980s, the U.S. steel industry came under increasing pressure from foreign competition. Manufacture in Germany and Japan was booming. Foreign mills and factories, built with the latest technology, benefited from lower labor costs and powerful government-corporate partnerships, allowing them to capture increasing market shares of steel and steel products. Separately, demand for steel softened due to recessions, the 1973 oil crisis, and increasing use of other materials.[5][37] At this critical juncture, free market and anti-union policies, and deregulation, especially under President Reagan, came into play.[37] These pressures only added to the U.S. steel industry's own internal problems, which included a now-outdated manufacturing base that had been over-expanded in the 1950s and 1960s, hostile management and labor relationships, the inflexibility of United Steelworkers regarding wage cuts and work-rule reforms, oligarchic management styles, and poor strategic planning by both union and management.[37] In particular, Pittsburgh faced its own challenges. Local coke and ore deposits were depleted, raising material costs. The large mills in the Pittsburgh region also faced competition from newer, more profitable "mini-mills" and non-union mills with lower labor costs[37]

Beginning in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the steel industry in Pittsburgh began to implode. Following the 1981–1982 recession, for example, the mills laid off 153,000 workers.[37] The steel mills began to shut down. These closures caused a ripple effect, as railroads, mines, and other factories across the region lost business and closed. The local economy suffered a depression, marked by high unemployment and underemployment, as laid-off workers took lower-paying, non-union jobs. Pittsburgh suffered as elsewhere in the Rust Belt with a declining population, and like many other U.S. cities, it also saw white flight to the suburbs.[38]

| Year | City Population | City Rank [3] | Population of the Urbanized Area [4] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 676,806 | 12 | 1,533,000 |

| 1960 | 604,332 | 16 | 1,804,000 |

| 1970 | 540,025 | 24 | 1,846,000 |

| 1980 | 423,938 | 30 | 1,810,000 |

| 1990 | 369,879 | 40 | 1,678,000 |

| 2000 | 334,563 | 51 | 1,753,000 |

Today there are no steel mills in Pittsburgh, although manufacture continues at regional mills, such as the Edgar Thomson Works in near-by Braddock. Beginning in the 1980s, Pittsburgh's economy shifted from heavy industry to services, medicine, higher education, tourism, banking, corporate headquarters and high technology. Today, the top two private employers in the city are the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (26,000 employees) and the University of Pittsburgh (10,700 employees).[39]

Despite the economic turmoil, civic improvements continued. In 1985, the J & L Steel Southside site was cleared and a High Technology Center was built.[21] In the 1980s, the Renaissance II urban revitalization created numerous new structures, such as PPG Place. In the 1990s, the former sites of the Homestead, Duquesne and South Side US Steel mills were cleared.[21] In 1992, the new terminal at Pittsburgh International Airport opened.[21] In 2001, Heinz Field and PNC Park opened.

Following these transformations, present-day Pittsburgh, with clean air, a diversified economy, a low cost of living, and a rich infrastructure for education and culture, has been ranked as one of the World's Most Livable Cities.[40]

See also

- Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

- List of Pittsburgh neighborhoods

- List of major corporations in Pittsburgh

- University of Pittsburgh

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 "A History of the Point," Fort Pitt Museum

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 "Pittsburgh," Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, 1911.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "The Greatest Journey," James Shreeve, National Geographic, March 2006, pg. 64. Shows dates for Rockshelter 19,000 to 12,000 years ago.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Crucible of War: The Seven Years' War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754–1766," Anderson, Fred; Knopf; New York, 2000.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 Lorant, Stefan (1999). Pittsburgh, The Story of an American City, 5th edition. Esselmont Books, LLC. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Lorant" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Burial Mound to Get Historical Marker, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 2001-05-13

- ↑ "Born to Die: Disease and New World Conquest, 1492–1650," Cook, Noble David; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998. ISBN 0521622085, ISBN 0521627303.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 "The Indian Wars of Pennsylvania," Sipe, C. Hale; 1831; Wennawoods Publishing reprint 1999

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Logstown, on the Ohio : a historical sketch", Agnew, Daniel, Myers, Shinkle & Co., Pittsburgh, PA, 1894. Historic Pittsburgh, pg. 7.

- ↑ "The Planting of Civilization in Western Pennsylvania," Buck, Solon J. (Solon Justus), Univ. of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, c1939, pg. 30. Historic Pittsburgh.

- ↑ "Course of study in geographic, biographic and historic Pittsburgh," The Board of Public Education, Pittsburgh, 1921. Historic Pittsburgh

- ↑ "History of Washington County, Pennsylvania" Crumrine, Boyd, L.H. Everts and Co., 1882, pg. 26.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "The Frontier Forts of Western Pennsylvania," Albert, George Dallas, C. M. Busch, state printer, Harrisburg, 1896. Historic Pittsburgh

- ↑ "The Diaries of George Washington, Vol. 1," Donald Jackson, ed., Dorothy Twohig, assoc. ed. Library of Congress American Memory site

- ↑ "Standard History of Pittsburg, Pennsylvania", edited by Erasmus Wilson, H.R. Cornell & Co., 1898, pg. 58. Available at Historic Pittsburgh.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 The Unwritten History of Braddock's Field (Pennsylvania), editor, Geo. H. Lamb, A. M., Nicholson printing co., Pittsburgh, 1917

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 "Keeping House, Women's Lives in Western Pennsylvania," Bartlett, Virginia K., Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania and University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, PA, 1994.

- ↑ "The Story of Grant's Hill," The Union Savings Bank, Pittsburgh, PA, c1934

- ↑ "Through one hundred and fifty years: the University of Pittsburgh," 1937, Agnes Lynch Starrett.

- ↑ "Monongahela, the river and its region," Wiley, Richard Taylor; The Ziegler company, c1937

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 21.5 21.6 21.7 21.8 21.9 Key Events in Pittsburgh History, WQED Pittsburgh History Site

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 Ballou's Pictorial, issue of 21 Feb 1857

- ↑ Darby's Emigrant's Guide, 1818

- ↑ Bridges and Tunnels of Allegheny County and Pittsburgh, PA

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 "A century and a half of Pittsburg and her people," Boucher, John Newton; The Lewis Publishing Company, 1908.

- ↑ "History of the Allegheny Fire Department," Allegheny Fire Dept., 1894/5

- ↑ Otto Krebs, Lithograph, 1874

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 28.4 28.5 28.6 History of Pittsburgh, Miriam Meislik, Ed Galloway, Society of American Archivists Annual Conference, Pittsburgh, PA, 1999.

- ↑ "Allegheny County's Hundred Years," Thurston, George H.; A. A. Anderson Son, Pittsburgh, 1888.

- ↑ "Harper's Weekly, Journal of Civilization," Vol XXL, No. 1076, New York, Saturday, August 11, 1877.

- ↑ "The Gospel of Wealth," Carnegie, Andrew, 1889.

- ↑ Thaddeus M. Fowler, Lithograph, 1902, From the Palmer Museum of Art of The Pennsylvania State University.

- ↑ "Cathedral of Learning," University of Pittsburgh

- ↑ "The 2002 Pittsburgh Jewish Community Study," Ukeles Associates, Inc., December 2002

- ↑ "Building the Igloo," PittsburghHeritage.com

- ↑ "History, Point State Park," Pennsylvania State Parks website

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 37.3 37.4 "And the Wolf Finally Came: The Decline of the American Steel Industry," John P. Hoerr, University of Pittsburgh Press, 1988.

- ↑ "Western PA History: Renaissance City: Corporate Center 1945–present," WQED's Pittsburgh History Teacher's Guide series

- ↑ "Top Private Employers, Pittsburgh Regional Alliance - Aug 2006

- ↑ Livability Ranking, Economist Intelligence Unit, October 2005

Bibliography

- Cannadine, Mellon (2007)

- Carson, Carolyn Leonard. Healing Body, Mind, and Spirit: The History of the St. Francis Medical Center, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Carnegie-Mellon U. Press, 1995. 246 pp.

- Thomas, Clarke M. Front-Page Pittsburgh: Two Hundred Years of the Post-Gazette. U. of Pittsburgh Press, 2005. 332 pp.

- Crowley, Gregory J. The Politics of Place: Contentious Urban Redevelopment in Pittsburgh. U. of Pittsburgh Press, 2005. 207 pp.

- Devault, Ileen A. Sons and Daughters of Labor: Class and Clerical Work in Turn-of-the-Century Pittsburgh. Cornell U. Press, 1991. 194 pp.

- Glasco, Laurence A., ed. The WPA History of the Negro in Pittsburgh. U. of Pittsburgh Press, 2004. 422 pp.

- Greenwald, Maurine W. and Anderson, Margo, eds. Pittsburgh Surveyed: Social Science and Social Reform in the Early Twentieth Century. U. of Pittsburgh Press, 1996. 292 pp.

- Harper, R. Eugene. The Transformation of Western Pennsylvania, 1770-1800. U. of Pittsburgh Press, 1991. 273 pp.

- Hays, Samuel P., ed. City at the Point: Essays on the Social History of Pittsburgh. U. of Pittsburgh Press, 1989. 473 pp.

- Heineman, Kenneth J. A Catholic New Deal: Religion and Reform in Depression Pittsburgh. Pennsylvania State U. Press, 1999. 287 pp.

- Hinshaw, John. Steel and Steelworkers: Race and Class Struggle in Twentieth-Century Pittsburgh. State U. of New York Press, 2002. 348 pp.

- Hoerr, John. And the Wolf Finally Came: The Decline of American Steel. U. of Pittsburgh Press, 1988. 689 pp.

- Holt, Michael 1850s

- Ingham, John N. Making Iron and Steel: Independent Mills in Pittsburgh, 1820-1920. Ohio State U. Press, 1991. 297 pp.

- Kleinberg, S. J. The Shadow of the Mills: Working-Class Families in Pittsburgh, 1870-1907. U. of Pittsburgh Press, 1989. 414 pp.

- Krause, Paul. The Battle for Homestead, 1880-1892: Politics, Culture, and Steel. U. of Pittsburgh Press, 1992. 548 pp.

- Lopez, Steven Henry. Reorganizing the Rust Belt: An Inside Study of the American Labor Movement. U. of California Press, 2004. 314 pp.

- Lorant, Stefan. Pittsburgh: The Story of an American City, (1964), well written, heavily illustrated popular history

- Lubove, Roy. Twentieth Century Pittsburgh: Government, Business, and Environmental Change (1969)

- Lubove, Roy. Twentieth-Century Pittsburgh. Vol. 2: The Post-Steel Era. U. of Pittsburgh Press, 1996. 413 pp. the major scholarly synthesis

- David Nasaw, Andrew Carnegie (2006)

- Pittsburgh Survey 5 vol

- Rishel, Joseph F. Founding Families of Pittsburgh: The Evolution of a Regional Elite, 1760-1910. U. of Pittsburgh Press, 1990. 241 pp.

- Rose, James D. Duquesne and the Rise of Steel Unionism. U. of Illinois Press, 2001. 284 pp.

- Ruck, Rob. Sandlot Seasons: Sport in Black Pittsburgh. U. of Illinois Press, 1987. 238 pp.

- Seely, Bruce E., ed. Iron and Steel in the Twentieth Century. Facts on File, 1994. 512 pp.

- Smith, Arthur G. Pittsburgh: Then and Now. U. of Pittsburgh Press, 1990. 336 pp.

- Smith, George David. From Monopoly to Competition: The Transformation of Alcoa, 1888-1986. Cambridge U. Press, 1988. 554 pp.

- Tarr, Joel A., ed. Devastation and Renewal: An Environmental History of Pittsburgh and Its Region. U. of Pittsburgh Press, 2003. 312 pp. online review

- Wade, Richard C. The Urban Frontier: The Rise of Western Cities, 1790-1830. (1959)

- Wall, Joseph. Andrew Carnegie (1970). 1137 pp.

- Weber, Michael P. Don't Call Me Boss: David L. Lawrence, Pittsburgh's Renaissance Mayor. U. of Pittsburgh Press, 1988. 440 pp.

Primary sources

- Lubove, Roy, ed. Pittsburgh 1976. 294 pp. short excerpts

External links

- Historic Pittsburgh. Provides historic materials from the University of Pittsburgh's University Library System, the Library & Archives of the Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania at the Senator John Heinz Pittsburgh Regional History Center, and the Carnegie Museum of Art.

- Pittsburgh History maintained by the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh

- Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation

- The History of Pittsburgh's Skyline