Archive:New Draft of the Week: Difference between revisions

imported>Milton Beychok (Weekly change) |

imported>Milton Beychok m (Added a new nomination) |

||

| Line 34: | Line 34: | ||

| <!-- specialist supporters --> | | <!-- specialist supporters --> | ||

| <!-- date created --> 2009-06-18 | | <!-- date created --> 2009-06-18 | ||

|- | |||

| <!-- article --> {{pl|Clean Air Act (U.S.)}} | |||

| <!-- score --> 1 | |||

| <!-- supporters --> [[User:Milton Beychok|Milton Beychok]]; | |||

| <!-- specialist supporters --> | |||

| <!-- date created --> 2009-06-27 | |||

|} | |} | ||

Revision as of 11:41, 16 July 2009

The New Draft of the Week is a chance to highlight a recently created Citizendium article that has just started down the road of becoming a Citizendium masterpiece.

It is chosen each week by vote in a manner similar to that of its sister project, the Article of the Week.

Add New Nominees Here

To add a new nominee or vote for an existing nominee, click edit for this section and follow the instructions

| Nominated article | Vote Score |

Supporters | Specialist supporters | Date created |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | Howard C. Berkowitz 15:22, 13 July 2009 (UTC) | Anthony.Sebastian | 2009-06-18 | |

| 3 | Paul Wormer; Milton Beychok; Meg Ireland | 2009-06-18 | ||

| 1 | Milton Beychok; | 2009-06-27 |

If you want to see how these nominees will look on the CZ home page (if selected as a winner), scroll down a little bit.

Transclusion of the above nominees (to be done by an Administrator)

- Transclude each of the nominees in the above "Table of Nominee" as per the instructions at Template:Featured Article Candidate.

- Then add the transcluded article to the list in the next section below, using the {{Featured Article Candidate}} template.

View Current Transcluded Nominees (after they have been transcluded by an Administrator)

The next New Draft of the Week will be the article with the most votes at 1 AM UTC on Thursday, 16 July 2009. I did the honors this time. Milton Beychok 01:11, 16 July 2009 (UTC)

| Nominated article | Supporters | Specialist supporters | Dates | Score | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The Air Quality Index (AQI), also known as the Air Pollution Index (API), Pollutant Standard Index (PSI) or Air Quality Health Index (AQHI), is a number used by government agencies to characterize the quality of the ambient air at a given location. As the AQI increases, the severity of probable adverse health effects increases as does the percentage of the population expected to be affected by the adverse health effects. To compute the AQI requires an air pollutant concentration to be obtained from an air quality monitoring station. The method used to convert from air pollutant concentrations to AQIs varies for each air pollutant, and is different in different countries. In many countries, air quality index values are divided into ranges, and each range is assigned a descriptor (i.e., a very few words describing the air quality or the health effects of the range) and often a color code as well. A government agency might also encourage members of the public to avoid strenuous activities, use public transportation rather than personal automobiles and work from home when AQI levels are high. Many countries monitor ground-level ozone, particulate matter (PM10), sulfur dioxide (S02), carbon monoxide (CO) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and calculate air quality indices for these pollutants. Most other air contaminants do not have an associated AQI. Air Quality Indices by country

CanadaEnvironment Canada, the national environmental protection agency of Canada, uses Air Quality Health Index (AQHI) categories ranging from 1 to 10+ and each category has an assigned color code (see adjacent table) that enables members of the general public to easily identify their health risks as indicated in published air quality forecasts.[1] As shown in the adjacent table:

As of 2009, many of the Canadian provinces, if not all, have adopted the AQHI categories implemented by Environment Canada. China

China's Ministry of Environmental Protection (MEP)[2][4] is responsible for monitoring the level of air pollution in China. As of August 2008, MEP monitors daily pollution level in its major cities and develops an Air Pollution Index (API) level that is based on the ambient air concentrations sulfur dioxide, nitrogen dioxide, particulate matter (PM10), carbon monoxide, and ozone as measured at monitoring stations in each of those major cities.[2][4] The adjacent table presents China's national API scale, which is not color coded and uses a scale 0 to more than 300, divided into five ranges of air quality categorized as excellent, good, slightly polluted, heavily polluted and hazardous. API MechanicsAn individual score is assigned to the level of each pollutant and the final API is the highest of those 5 scores. The pollutant concentrations are obtained quite differently. Sulfur dioxide, nitrogen dioxide and PM10 concentrations are obtained as daily averages. Carbon monoxide and ozone are more harmful and are obtained as an hourly averages. The final API value is calculated as a daily average.[2][4] The scale for each pollutant is non-linear, as is the final daily API value. Thus, an API value of 100 does not mean it is twice the pollution of API at 50, nor does it mean it is twice as harmful. Beijing's APIChina's capitol city, Beijing, has its own API scale, which was developed by the Beijing Municipal Environmental Protection Bureau.[5] As can be seen in the adjacent table, the API scale used by Beijing differs quite significantly from China's national scale in that: • The Beijing scale ranges from 0 to 500 (rather than 0 to 300 as in the national scale) Hong KongThe Hong Kong Environmental Protection Department (Hong Kong EPD) has developed a color coded Air Pollution Index (API) based upon the measured concentrations of ambient particulate matter (PM10), sulfur dioxide, carbon monoxide, ozone and nitrogen dioxide over a 24-hour period. Hong Kong's color coded Air Pollution Index (API) scale ranges from 0 to 500 corresponding to adverse health effects that range from low to severe as shown in the adjacent chart:[3]

Although Hong Kong is now part of China, it can be seen that Hong Kong's API scale differs from both China's scale and Beijing's scale.

MalaysiaThe air quality in Malaysia is described in terms of an Air Pollutant Index (API). The API is an indicator of air quality and was developed based on scientific assessment to indicate in an easily understood manner, the presence of pollutants and its impact on health. The API system of Malaysia closely follows the similar system developed by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA). As shown in the adjacent table, Malaysia does not color code their air quality categories. Monitoring stations measure the concentration of five major pollutants in the ambient air: PM10, sulfur dioxide, nitrogen dioxide, carbon monoxide and ozone. These concentrations are measured continuously on an hourly basis. The hourly value is then averaged over a 24-hour period for PM110 and sulfur dioxide and an 8-hour period for carbon monoxide. The ozone and nitrogen dioxide are read hourly. An hourly index is then calculated for each pollutant. The highest hourly index value is then taken as the API for the hour. When the API exceeds 500, a state of emergency is declared in the reporting area. Usually, this means that non-essential government services are suspended, and all ports in the affected area closed. There may also be a prohibition on private sector commercial and industrial activities in the reporting area excluding the food sector.

MexicoThe air quality in Mexico is described and reported hourly in terms of a color coded Metropolitan Index of Air Quality (IMECA), developed by the Ministry of the Environment for the Government of the Federal District. The IMECA is calculated from the results of real-time monitoring of the ambient concentrations of ozone, sulfur dioxide, nitrogen dioxide, carbon monoxide and particulate matter (PM10). The IMECA was developed specifically for the Federal District of Mexico which only encompasses Mexico City and its surrounding suburbs and adjacent municipalities. The real-time monitoring of the ambient atmosphere is performed by the Sistema de Monitoreo Atmosférico de la Ciudad de México (SIMAT or System of Atmospheric Monitoring for Mexico City). SIMAT's real-time monitoring includes monitoring of the ultra-violet (UV) radiation from the sun and the results are also described and reported hourly as IUVs (Índice de Radiación Ultravioleta) in a manner that is similar to the reporting of the IMECAs.[8]

SingaporeSingapore's National Environment Agency (NEA) in the Ministry of the Environment and Water Resources (MEWR) has the responsibility for the real-time monitoring of the concentrations of sulfur dioxide, nitrogen dioxide, carbon monoxide, ozone and PM10 in the ambient air of Singapore. The real-time monitoring of the ambient air quality is done by a telemetric network of air quality monitoring stations strategically located in different parts of Singapore. The NEA uses the real-time monitoring data to obtain and report 24-hour Pollution Standard Index (PSI) levels along with their corresponding air quality categories as shown in the adjacent table and which does not use color coding.[9] The NEA states that the PSI scale developed for use in Singapore is very similar to the scale developed and used by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The NEA also further states that the National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) developed by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency are used to assess Singapore's air quality. Although the adjacent table indicates that the NEA categorizes a 24-hour PSI level that is higher than 300 as being hazardous, the NEA also considers a 24-hour PSI level higher than 400 to be life-threatening to ill and elderly persons.[10]

United KingdomAEA Technology, a British environmental consulting company, issues air quality forecasts for the United Kingdom (UK) on behalf of the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra).[11] The scale used in the United Kingdom is an Air Pollution Index (API) with levels ranging from 1 to 10 as shown in the attached table and it is color coded. The scale was thoroughly studied and approved by the United Kingdom's government advisory body, namely the "Committee on Medical Effects of Air Pollution Episodes" (COMEAP).[11] The scale is based on continuous monitoring, in locations throughout the United Kingdom, of the ambient air for the concentrations of the major air pollutants, namely sulfur dioxide, nitrogen dioxide, ozone, carbon monoxide and PM10. The forecasts issued by AEA Technology are based on the prediction of air pollution index for the worst-case of the five pollutants. As shown in the adjacent table, the health effect of each API range is referred to as its banding rather than as its category. The health effect bandings for the API ranges are low, moderate, high and very high.

United StatesThe Air Quality Index (AQI) ranges used by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) and their corresponding health effect categories and color codes are provided in the adjacent table. The U.S. EPA's AQI is also known as the Pollution Standards Index (PSI). If multiple pollutants are measured at a monitoring site, then the largest or "dominant" AQI value is reported for the location. The U.S. EPA has developed conversion calculators, available online,[13][14] for the conversion of AQI values to concentration values and for the reverse conversion of concentrations to AQI values. A national map of the United States of America containing daily AQI forecasts across the nation, developed jointly by the U.S. EPA and NOAA is also available online.[15] The U.S. Clean Air Act requires the U.S. EPA to review its National Ambient Air Quality Standards[16] every five years to reflect evolving health effects information. The Air Quality Index is adjusted periodically to reflect these changes. Air pollutant concentration measurement unitsIn the United States, the concentrations of the air pollutants involved in the AQI are usually expressed as:

References

|

Paul Wormer; Milton Beychok; Meg Ireland | 3

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

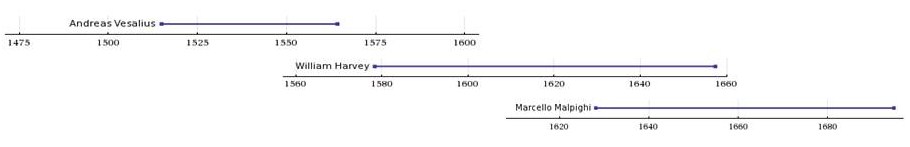

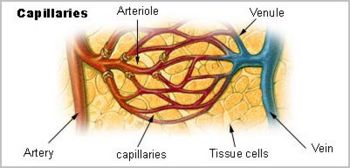

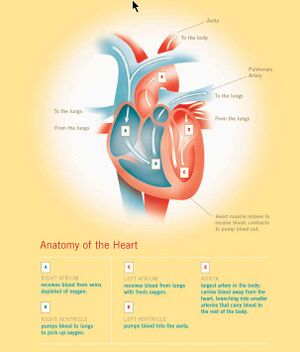

(PD) Image: From book: William Harvey, by D'Arcy Power, 1897 William Harvey. From book of that name by D'Arcy Power, 1897  (PD) Image: Levine & Associates, Inc. for U.S National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Aging at: http://bit.ly/MnJaE Anatomy of the Human Heart. For enlarged version of this image showing more detail, click here. William Harvey (1578-1657) bestowed on humanity one of the most important advances in the history of medical science — an explanation of the core physiology of the human cardiovascular system. In part by introducing quantitative methods into anatomical and physiological investigations, Harvey discovered that the left ventricle of the heart pumps blood through the body, doing so via a system of vessels such that the blood moves in a circular path,[1] from the left side of the heart through the arteries and back to the right side of the heart through the veins, transiting from the right side of the heart to the left via blood vessels in the lung, the two sides of the heart separated by a blood-impermeable septum. He published those findings in his 1628 book, Exercitatio Anatomica de Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in Animalibus (Anatomical Exercises on the Motion of the Heart and Blood in Animals), usually referred to as De Motu Cordis.[2] [3] [4] In his dissections of humans and animals, Harvey could not see vessels connecting the arteries to the veins, since, as it turns out, their minute size lies below the limits of visual acuity, even with the magnifying glass he used in his work. He had no access, and perhaps no knowledge, of the existence of microscopes, however primitive their state. Harvey could only infer that a connecting pathway existed. In 1661, a few years after Harvey died, the Italian biologist, Marcello Malpighi (1628-1694), using one of the early microscopes, discovered capillaries, tiny blood vessels not visible to the naked eye, connecting arteries to veins. In a seemingly fitting coincidence, Malpighi had entered the world the same year Harvey published De Motu Cordis. In works published little more than a century apart, 1543 to 1661, three men, Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564), William Harvey (1578-1657), and Marcello Malpighi (1628-1694), demonstrated central truths of human anatomy and physiology that had escaped Western medicine for more than a millennium following the erroneous teachings of the influential Greek physician, Galen of Pergamum (130-216 CE). It required three investigators to break the stranglehold of one.

William Harvey’s Major ContributionsAdapted from Sherwin B. Nuland (2008)[5]

Brief sketch of Williams Harvey’s lifeBorn in 1578 (April 1, at Folkstone, on the east coast of Kent, England), of Thomas and Joan Harvey, as the eldest of seven brothers and two sisters (a "week of brothers" and a "brace of sisters"), William Harvey entered the world shortly after Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564) had died, though Vesalius's reputation had not died, owing to his remarkably detailed and elegantly drawn illustrations revolutionizing the understanding of human anatomy.[7] [8] [9] For his anatomical work, William Harvey had Vesalius's giant shoulders to stand on, and ultimately he saw further. Harvey received his early education in the classics, in Canterbury, at King's School (1588-1593), there "....admonished to speak Greek or Latin even on the playground." [6] Harvey's father, a landowner and successful merchant, could afford to send Harvey to the University of Cambridge (specifically, Gonville and Caius College), which he entered at age 16 years (1593) and received his Bachelor of Arts (B.A.) degree at age 19 years (1597). Harvey developed an interest in medicine and decided to go to Italy, one of the major centers of intellectual activity in Europe at the time. He enrolled in the then renown University of Padua, studying medicine under Hieronymus Fabricius of Aquapendente, a noted anatomist in the Vesalian tradition, who had discovered the valves in the veins, a discovery which later contributed to Harvey's thinking that led to his discovery of the blood circulatory system.[10] Harvey's earlier education in the classics helped ease his learning at Padua, as lecturers spoke in Latin. Harvey received his Doctor of Medicine degree in April, 1602, at age 24 years.[11] After Padua, Harvey returned to England and developed a practice in medicine, married, and became a Fellow of the College of Physicians in London. He also secured a position as physician at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, one of London’s great hospitals, and there and in his private practice distinguished himself as a physician. In 1615, at age 37 years, the College of Physicians elected him their Professor of Anatomy and Surgery, and gave him the honor of the Lumleian Lectureship, a lifetime remunerated position, in which he lectured on human anatomy, physiology and surgery, including performing demonstration dissections on human corpses, officially twice per week, from 1616 to 1656, the year before he died. The lecturership gave Harvey a great opportunity to organize his thinking and guide his research. His lecture notes survive as Lectures on the Whole of Anatomy as a manuscript in the British Library and in English translation.[12]

In 1618 Harvey became physician extraordinary to the king (James I), and ministered to many eminent aristocrats, including Francis Bacon, for whom he had little regard as an intellectual. After Charles I succeeded the throne, in 1625, Harvey became Charles' physician, benefitting from the King’s patronage to pursue his medical investigations. When civil strife engulfed England, Harvey, now in his 60s retired to live with a brother, pursuing his experiments until he died in 1657, having lived nearly to the age of 80 years.[14] [15] De Motu CordisTo read the full-text of De Motu Cordis in English translation, click on the "Works" tab in the banner at the beginning of this page. Equivalently, click De Motus Cordis, which brings you to same subpage of this article. A few revelatory quotes from the work:

Of course, we now know that the richer 'spirit' in arterial blood is oxygen. Before the discovery of oxygen, the alchemists of the seventeenth century recognized that air contained an essential ingredient, an 'elixir of life' — a kind of 'spirit'. We also know today that venous blood, too, has its richer 'spirit', carbon dioxide (as bicarbonate). De Generatione AnimaliumHarvey received less repute for his other great work, De Generatione Animalium — On the Generation of Animals — a contribution to embryology.... References cited and notes

|

Anthony Sebastian; Howard C. Berkowitz | 3

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Current Winner (to be selected and implemented by an Administrator)

To change, click edit and follow the instructions, or see documentation at {{Featured Article}}.

| The metadata subpage is missing. You can start it via filling in this form or by following the instructions that come up after clicking on the [show] link to the right. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Heat is a form of energy that is transferred between two bodies that are in thermal contact and have different temperatures. For instance, the bodies may be two compartments of a vessel separated by a heat-conducting wall and containing fluids of different temperatures on either side of the wall. Or one body may consist of hot radiating gas and the other may be a kettle with cold water, as shown in the picture. Heat flows spontaneously from the higher-temperature to the lower-temperature body. The effect of this transfer of energy usually, but not always, is an increase in the temperature of the colder body and a decrease in the temperature of the hotter body.

Change of aggregation state

A vessel containing a fluid may lose or gain energy without a change in temperature when the fluid changes from one aggregation state to another. For instance, a gas condensing to a liquid does this at a certain fixed temperature (the boiling point of the liquid) and releases condensation energy. When a vessel, containing a condensing gas, loses heat to a colder body, then, as long as there is still vapor left in it, its temperature remains constant at the boiling point of the liquid, even while it is losing heat to the colder body. In a similar way, when the colder body is a vessel containing a melting solid, its temperature will remain constant while it is receiving heat from a hotter body, as long as not all solid has been molten. Only after all of the solid has been molten and the heat transport continues, the temperature of the colder body (then containing only liquid) will rise.

For example, the temperature of the tap water in the kettle shown in the figure will rise quickly to the boiling point of water (100 °C). Then, when the flame is not switched off, the temperature inside the kettle remains constant at 100 °C for quite some time, even though heat keeps on flowing from flame to kettle. When all liquid water has evaporated—when the kettle has boiled dry—the temperature of the kettle will quickly rise again until it obtains the temperature of the burning gas, then the heat flow will finally stop. (Most likely, though, the handle and maybe the metal of the kettle, too, will have melted before that).

Units

At present the unit for the amount of heat is the same as for any form of energy. Before the equivalence of mechanical work and heat was clearly recognized, two units were used. The calorie was the amount of heat necessary to raise the temperature of one gram of water from 14.5 to 15.5 °C and the unit of mechanical work was basically defined by force times path length (in the old cgs system of units this is erg). Now there is one unit for all forms of energy, including heat. In the International System of Units (SI) it is the joule, but the British Thermal Unit and calorie are still occasionally used. The unit for the rate of heat transfer is the watt (J/s).

Equivalence of heat and work

Although heat and work are forms of energy that both obey the law of conservation of energy, they are not completely equivalent. Work can be completely converted into heat, but the converse is not true. When converting heat into work, part of the heat is not—and cannot be—converted to work, but flows to the body of lower temperature that is out of necessity present to generate a heat flow.

Heat and temperature

The important distinction between heat and temperature (heat being a form of energy and temperature a measure of the amount of that energy present in a body) was clarified by Count Rumford, James Prescott Joule, Julius Robert Mayer, Rudolf Clausius, and others during the late 18th and 19th centuries. Also it became clear by the work of these men that heat is not an invisible and weightless fluid, named caloric, as was thought by many 18th century scientists, but a form of motion. The molecules of the hotter body are (on the average) in more rapid motion than those of the colder body. The first law of thermodynamics, discovered around the middle of the 19th century, states that the (flow of) heat is a transfer of part of the internal energy of the bodies. In the case of ideal gases, internal energy consists only of kinetic energy and it is indeed only this motional energy that is transferred when heat is exchanged between two containers with ideal gases. In the case of non-ideal gases, liquids and solids, internal energy also contains the averaged inter-particle potential energy (attraction and repulsion between molecules), which depends on temperature. So, for non-ideal gases, liquids and solids, also potential energy is transferred when heat transfer occurs.

Forms of heat

The actual transport of heat may proceed by electromagnetic radiation (as an example one may think of an electric heater where usually heat is transferred to its surroundings by infrared radiation, or of a microwave oven where heat is given off to food by microwaves), conduction (for instance through a metal wall; metals conduct heat by the aid of their almost free electrons), and convection (for instance by air flow or water circulation).

Entropy

If two systems, 1 (cold) and 2 (hot), are isolated from the rest of the universe (i.e., no other heat flows than from 2 to 1 and no work is performed on the two systems) then the entropy Stot = S1 + S2 of the total system 1 + 2 increases upon the spontaneous flow of heat. This is in accordance with the second law of thermodynamics that states that spontaneous thermodynamic processes are associated with entropy increase. In general, the entropy S of a system at absolute temperature T increases with

when it receives an amount of heat Q > 0. Entropy is an additive (size-extensive) property.

The hotter system 2 loses an amount of heat to the colder system 1. In absolute value the exchanged amounts of heat are the same by the law of conservation of energy (no energy escapes to the rest of the universe), hence

Here it is assumed that the amount of heat Q is so small that the temperatures of the two systems are constant. One can achieve this by considering a small time interval of heat exchange and/or very large systems.

Remark: the expression ΔS = Q/T is only strictly valid for a reversible (also known as quasistatic) flow of energy. It is possible[1] to define:

It is assumed that ΔSint is much smaller than ΔSext, so that it can be neglected.

Semantic caveats

It is strictly speaking not correct to say that a hot object "possesses much heat"—it is correct to say, however, that it possesses high internal energy. The word "heat" is reserved to describe the process of transfer of energy from a high temperature object to a lower temperature one (in short called "heating of the cold object"). The reason that the word "heat" is to be avoided for the internal energy of an object is that the latter can have been acquired either by heating or by work done on it (or by both). When we measure internal energy, there is no way of deciding how the object acquired it—by work or by heat. In the same way as one does not say that a hot object "possesses much work", one does not say that it "possesses much heat". Yet, terms as "heat reservoir" (a system of temperature higher than its environment that for all practical purposes is infinite) and "heat content" (a synonym for enthalpy) are commonly used and are incorrect by the same reasoning.

The molecules of a hot body are in agitated motion and, as said, it cannot be measured how they became agitated, by work or by heat. Often, especially outside physics, the random molecular motion is referred to as "thermal energy". In classical (phenomenological) thermodynamics this is an intuitive, but undefined, concept. In statistical thermodynamics, thermal energy could be defined (but rarely ever is) as the average kinetic energy of the molecules constituting the body. Kinetic and potential energy of molecules are concepts that are foreign to classical thermodynamics, which predates the general acceptance of the existence of molecules.

Quotation

As a result Carathéodory was able to obtain the laws of thermodynamics without recourse to fictitious machines or objectionable concepts as the flow of heat.[2]

Reference

Previous Winners

Continuum hypothesis: A statement about the size of the continuum, i.e., the number of elements in the set of real numbers. [e] (July 9)

Continuum hypothesis: A statement about the size of the continuum, i.e., the number of elements in the set of real numbers. [e] (July 9) Hawaiian alphabet: The form of writing used in the Hawaiian Language [e] (July 2)

Hawaiian alphabet: The form of writing used in the Hawaiian Language [e] (July 2) Now and Zen: A 1988 studio album recorded by Robert Plant, with guest contributions from Jimmy Page. [e] (June 25)

Now and Zen: A 1988 studio album recorded by Robert Plant, with guest contributions from Jimmy Page. [e] (June 25) Wrench (tool): A fastening tool used to tighten or loosen threaded fasteners, with one end that makes firm contact with flat surfaces of the fastener, and the other end providing a means of applying force [e] (June 18)

Wrench (tool): A fastening tool used to tighten or loosen threaded fasteners, with one end that makes firm contact with flat surfaces of the fastener, and the other end providing a means of applying force [e] (June 18) Air preheater: A general term to describe any device designed to preheat the combustion air used in a fuel-burning furnace for the purpose of increasing the thermal efficiency of the furnace. [e] (June 11)

Air preheater: A general term to describe any device designed to preheat the combustion air used in a fuel-burning furnace for the purpose of increasing the thermal efficiency of the furnace. [e] (June 11) 2009 H1N1 influenza virus: A contagious influenza A virus discovered in April 2009, commonly known as swine flu. [e] (June 4)

2009 H1N1 influenza virus: A contagious influenza A virus discovered in April 2009, commonly known as swine flu. [e] (June 4) Gasoline: A fuel for spark-ignited internal combustion engines derived from petroleum crude oil. [e] (21 May)

Gasoline: A fuel for spark-ignited internal combustion engines derived from petroleum crude oil. [e] (21 May) John Brock: Fictional British secret agent who starred in three 1960s thrillers by Desmond Skirrow. [e] (8 May)

John Brock: Fictional British secret agent who starred in three 1960s thrillers by Desmond Skirrow. [e] (8 May) McGuffey Readers: A set of highly influential school textbooks used in the 19th and early 20th centuries in the elementary grades in the United States. [e] (14 Apr)

McGuffey Readers: A set of highly influential school textbooks used in the 19th and early 20th centuries in the elementary grades in the United States. [e] (14 Apr) Vector rotation: Process of rotating one unit vector into a second unit vector. [e] (7 Apr)

Vector rotation: Process of rotating one unit vector into a second unit vector. [e] (7 Apr) Leptin: Hormone secreted by adipocytes that regulates appetite. [e] (31 Mar)

Leptin: Hormone secreted by adipocytes that regulates appetite. [e] (31 Mar) Kansas v. Crane: A 2002 decision of the Supreme Court of the United States, ruling that a person could not be adjudicated a sexual predator and put in indefinite medical confinement, purely on assessment of an emotional disorder, but such action required proof of a likelihood of uncontrollable impulse presenting a clear and present danger. [e] (24 Mar)

Kansas v. Crane: A 2002 decision of the Supreme Court of the United States, ruling that a person could not be adjudicated a sexual predator and put in indefinite medical confinement, purely on assessment of an emotional disorder, but such action required proof of a likelihood of uncontrollable impulse presenting a clear and present danger. [e] (24 Mar) Punch card: A term for cards used for storing information. Herman Hollerith is credited with the invention of the media for storing information from the United States Census of 1890. [e] (17 Mar)

Punch card: A term for cards used for storing information. Herman Hollerith is credited with the invention of the media for storing information from the United States Census of 1890. [e] (17 Mar) Jass–Belote card games: A group of trick-taking card games in which the Jack and Nine of trumps are the highest trumps. [e] (10 Mar)

Jass–Belote card games: A group of trick-taking card games in which the Jack and Nine of trumps are the highest trumps. [e] (10 Mar) Leptotes (orchid): A genus of orchids formed by nine small species that exist primarily in the dry jungles of South and Southeast Brazil. [e] (3 Mar)

Leptotes (orchid): A genus of orchids formed by nine small species that exist primarily in the dry jungles of South and Southeast Brazil. [e] (3 Mar) Worm (computers): A form of malware that can spread, among networked computers, without human interaction. [e] (24 Feb)

Worm (computers): A form of malware that can spread, among networked computers, without human interaction. [e] (24 Feb) Joseph Black: (1728 – 1799) Scottish physicist and chemist, known for his discoveries of latent heat, specific heat, and carbon dioxide [e] (11 Feb 2009)

Joseph Black: (1728 – 1799) Scottish physicist and chemist, known for his discoveries of latent heat, specific heat, and carbon dioxide [e] (11 Feb 2009) Sympathetic magic: The cultural concept that a symbol, or small aspect, of a more powerful entity can, as desired by the user, invoke or compel that entity [e] (17 Jan 2009)

Sympathetic magic: The cultural concept that a symbol, or small aspect, of a more powerful entity can, as desired by the user, invoke or compel that entity [e] (17 Jan 2009) Dien Bien Phu: Site in northern Vietnam of a 1954 decisive battle that soon forced France to relinquish control of colonial Indochina. [e] (25 Dec)

Dien Bien Phu: Site in northern Vietnam of a 1954 decisive battle that soon forced France to relinquish control of colonial Indochina. [e] (25 Dec) Blade Runner: 1982 science fiction film directed by Ridley Scott and starring Harrison Ford, set in an imagined Los Angeles of 2019. [e] (25 Nov)

Blade Runner: 1982 science fiction film directed by Ridley Scott and starring Harrison Ford, set in an imagined Los Angeles of 2019. [e] (25 Nov) Piquet: A two-handed card game played with 32 cards that originated in France around 1500. [e] (18 Nov)

Piquet: A two-handed card game played with 32 cards that originated in France around 1500. [e] (18 Nov) Crash of 2008: the international banking crisis that followed the subprime mortgage crisis of 2007. [e] (23 Oct)

Crash of 2008: the international banking crisis that followed the subprime mortgage crisis of 2007. [e] (23 Oct)- Information Management: Add brief definition or description (31 Aug)

Battle of Gettysburg: A turning point in the American Civil War, July 1-3, 1863, on the outskirts of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. [e] (8 July)

Battle of Gettysburg: A turning point in the American Civil War, July 1-3, 1863, on the outskirts of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. [e] (8 July) Drugs banned from the Olympics: Substances prohibited for use by athletes prior to, and during competing in the Olympics. [e] (1 July)

Drugs banned from the Olympics: Substances prohibited for use by athletes prior to, and during competing in the Olympics. [e] (1 July) Sea glass: Formed when broken pieces of glass from bottles, tableware, and other items that have been lost or discarded are worn down and rounded by tumbling in the waves along the shores of oceans and large lakes. [e] (24 June)

Sea glass: Formed when broken pieces of glass from bottles, tableware, and other items that have been lost or discarded are worn down and rounded by tumbling in the waves along the shores of oceans and large lakes. [e] (24 June) Dazed and Confused (Led Zeppelin song): Landmark 1969 song recorded by Led Zeppelin for their eponymous debut album, which became an early centrepiece for the group's live performances. [e] (17 June)

Dazed and Confused (Led Zeppelin song): Landmark 1969 song recorded by Led Zeppelin for their eponymous debut album, which became an early centrepiece for the group's live performances. [e] (17 June) Hirohito: The 124th and longest-reigning Emperor of Japan, 1926-89. [e] (10 June)

Hirohito: The 124th and longest-reigning Emperor of Japan, 1926-89. [e] (10 June) Henry Kissinger: (1923—) American academic, diplomat, and simultaneously Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs and Secretary of State in the Nixon Administration; promoted realism (foreign policy) and détente with China and the Soviet Union; shared 1973 Nobel Peace Prize for ending the Vietnam War; Director, Atlantic Council [e] (3 June)

Henry Kissinger: (1923—) American academic, diplomat, and simultaneously Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs and Secretary of State in the Nixon Administration; promoted realism (foreign policy) and détente with China and the Soviet Union; shared 1973 Nobel Peace Prize for ending the Vietnam War; Director, Atlantic Council [e] (3 June) Palatalization: An umbrella term for several processes of assimilation in phonetics and phonology, by which the articulation of a consonant is changed under the influence of a preceding or following front vowel or a palatal or palatalized consonant. [e] (27 May)

Palatalization: An umbrella term for several processes of assimilation in phonetics and phonology, by which the articulation of a consonant is changed under the influence of a preceding or following front vowel or a palatal or palatalized consonant. [e] (27 May) Intelligence on the Korean War: The collection and analysis, primarily by the United States with South Korean help, of information that predicted the 1950 invasion of South Korea, and the plans and capabilities of the enemy once the war had started [e] (20 May)

Intelligence on the Korean War: The collection and analysis, primarily by the United States with South Korean help, of information that predicted the 1950 invasion of South Korea, and the plans and capabilities of the enemy once the war had started [e] (20 May) Trinity United Church of Christ, Chicago: A predominantly black church located in south Chicago with upwards of 10,000 members, established in 1961. [e] (13 May)

Trinity United Church of Christ, Chicago: A predominantly black church located in south Chicago with upwards of 10,000 members, established in 1961. [e] (13 May) BIOS: Part of many modern computers responsible for basic functions such as controlling the keyboard or booting up an operating system. [e] (6 May)

BIOS: Part of many modern computers responsible for basic functions such as controlling the keyboard or booting up an operating system. [e] (6 May) Miniature Fox Terrier: A small Australian vermin-routing terrier, developed from 19th Century Fox Terriers and Fox Terrier types. [e] (23 April)

Miniature Fox Terrier: A small Australian vermin-routing terrier, developed from 19th Century Fox Terriers and Fox Terrier types. [e] (23 April) Joseph II: (1741–1790), Holy Roman Emperor and ruler of the Hapsburg (Austrian) territories who was the arch-embodiment of the Enlightenment spirit of the later 18th-century reforming monarchs. [e] (15 Apr)

Joseph II: (1741–1790), Holy Roman Emperor and ruler of the Hapsburg (Austrian) territories who was the arch-embodiment of the Enlightenment spirit of the later 18th-century reforming monarchs. [e] (15 Apr) British and American English: A comparison between these two language variants in terms of vocabulary, spelling and pronunciation. [e] (7 Apr)

British and American English: A comparison between these two language variants in terms of vocabulary, spelling and pronunciation. [e] (7 Apr) Count Rumford: (1753–1814) An American born soldier, statesman, scientist, inventor and social reformer. [e] (1 April)

Count Rumford: (1753–1814) An American born soldier, statesman, scientist, inventor and social reformer. [e] (1 April) Whale meat: The edible flesh of various species of whale. [e] (25 March)

Whale meat: The edible flesh of various species of whale. [e] (25 March) Naval guns: Artillery weapons on ships, and techniques and devices for aiming them. [e] (18 March)

Naval guns: Artillery weapons on ships, and techniques and devices for aiming them. [e] (18 March) Sri Lanka: An island nation in South Asia, located 31 km off the south-east coast of India, formerly known as Ceylon . [e] (11 March)

Sri Lanka: An island nation in South Asia, located 31 km off the south-east coast of India, formerly known as Ceylon . [e] (11 March) Led Zeppelin: English hard rock and blues group formed in 1968, known for their albums and stage shows. [e] (4 March)

Led Zeppelin: English hard rock and blues group formed in 1968, known for their albums and stage shows. [e] (4 March) Martin Luther: Add brief definition or description (20 February)

Martin Luther: Add brief definition or description (20 February) Cosmology: Add brief definition or description (4 February)

Cosmology: Add brief definition or description (4 February) Ernest Rutherford: Add brief definition or description(28 January)

Ernest Rutherford: Add brief definition or description(28 January) Edinburgh: Add brief definition or description (21 January)

Edinburgh: Add brief definition or description (21 January) Russian Revolution of 1905: Add brief definition or description (8 January 2008)

Russian Revolution of 1905: Add brief definition or description (8 January 2008) Phosphorus: Add brief definition or description (31 December)

Phosphorus: Add brief definition or description (31 December) John Tyler: Add brief definition or description (6 December)

John Tyler: Add brief definition or description (6 December) Banana: Add brief definition or description (22 November)

Banana: Add brief definition or description (22 November) Augustin-Louis Cauchy: Add brief definition or description (15 November)

Augustin-Louis Cauchy: Add brief definition or description (15 November)- B-17: Add brief definition or description - 8 November 2007

Red Sea Urchin: Add brief definition or description - 1 November 2007

Red Sea Urchin: Add brief definition or description - 1 November 2007 Symphony: Add brief definition or description - 25 October 2007

Symphony: Add brief definition or description - 25 October 2007 Oxygen: Add brief definition or description - 18 October 2007

Oxygen: Add brief definition or description - 18 October 2007 Origins and architecture of the Taj Mahal: Add brief definition or description - 11 October 2007

Origins and architecture of the Taj Mahal: Add brief definition or description - 11 October 2007 Fossilization (palaeontology): Add brief definition or description - 4 October 2007

Fossilization (palaeontology): Add brief definition or description - 4 October 2007 Cradle of Humankind: Add brief definition or description - 27 September 2007

Cradle of Humankind: Add brief definition or description - 27 September 2007 John Adams: Add brief definition or description - 20 September 2007

John Adams: Add brief definition or description - 20 September 2007 Quakers: Add brief definition or description - 13 September 2007

Quakers: Add brief definition or description - 13 September 2007 Scarborough Castle: Add brief definition or description - 6 September 2007

Scarborough Castle: Add brief definition or description - 6 September 2007 Jane Addams: Add brief definition or description - 30 August 2007

Jane Addams: Add brief definition or description - 30 August 2007 Epidemiology: Add brief definition or description - 23 August 2007

Epidemiology: Add brief definition or description - 23 August 2007 Gay community: Add brief definition or description - 16 August 2007

Gay community: Add brief definition or description - 16 August 2007 Edward I: Add brief definition or description - 9 August 2007

Edward I: Add brief definition or description - 9 August 2007

Rules and Procedure

Rules

- The primary criterion of eligibility for a new draft is that it must have been ranked as a status 1 or 2 (developed or developing), as documented in the History of the article's Metadate template, no more than one month before the date of the next selection (currently every Thursday).

- Any Citizen may nominate a draft.

- No Citizen may have nominated more than one article listed under "current nominees" at a time.

- The article's nominator is indicated simply by the first name in the list of votes (see below).

- At least for now--while the project is still small--you may nominate and vote for drafts of which you are a main author.

- An article can be the New Draft of the Week only once. Nominated articles that have won this honor should be removed from the list and added to the list of previous winners.

- Comments on nominations should be made on the article's talk page.

- Any draft will be deleted when it is past its "last date eligible". Don't worry if this happens to your article; consider nominating it as the Article of the Week.

- If an editor believes that a nominee in his or her area of expertise is ineligible (perhaps due to obvious and embarrassing problems) he or she may remove the draft from consideration. The editor must indicate the reasons why he has done so on the nominated article's talk page.

Nomination

See above section "Add New Nominees Here".

Voting

- To vote, add your name and date in the Supporters column next to an article title, after other supporters for that article, by signing

<br />~~~~. (The date is necessary so that we can determine when the last vote was added.) Your vote is alloted a score of 1. - Add your name in the Specialist supporters column only if you are an editor who is an expert about the topic in question. Your vote is alloted a score of 1 for articles that you created and 2 for articles that you did not create.

- You may vote for as many articles as you wish, and each vote counts separately, but you can only nominate one at a time; see above. You could, theoretically, vote for every nominated article on the page, but this would be pointless.

Ranking

- The list of articles is sorted by number of votes first, then alphabetically.

- Admins should make sure that the votes are correctly tallied, but anyone may do this. Note that "Specialist Votes" are worth 3 points.

Updating

- Each Thursday, one of the admins listed below should move the winning article to the Current Winner section of this page, announce the winner on Citizendium-L and update the "previous winning drafts" section accordingly.

- The winning article will be the article at the top of the list (ie the one with the most votes).

- In the event of two or more having the same number of votes :

- The article with the most specialist supporters is used. Should this fail to produce a winner, the article appearing first by English alphabetical order is used.

- The remaining winning articles are guaranteed this position in the following weeks, again in alphabetical order. No further voting should take place on these, which remain at the top of the table with notices to that effect. Further nominations and voting take place to determine future winning articles for the following weeks.

- Winning articles may be named New Draft of the Week beyond their last eligible date if their circumstances are so described above.

- The article with the most specialist supporters is used. Should this fail to produce a winner, the article appearing first by English alphabetical order is used.

Administrators

The Administrators of this program are the same as the admins for CZ:Article of the Week.

References

See Also

- CZ:Article of the Week

- CZ:Markup tags for partial transclusion of selected text in an article

- CZ:Monthly Write-a-Thon

| Citizendium Initiatives | ||

|---|---|---|

| Eduzendium | Featured Article | Recruitment | Subpages | Core Articles | Uncategorized pages | Requested Articles | Feedback Requests | Wanted Articles |

|width=10% align=center style="background:#F5F5F5"| |}