Australopithecus afarensis: Difference between revisions

imported>John S. Murphy No edit summary |

imported>John S. Murphy No edit summary |

||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

[[Image:Notcont3366.jpg|right|thumb|350px|{{#ifexist:Template:Notcont3366.jpg/credit|{{Notcont3366.jpg/credit}}<br/>|}}Selam (Lucy's Baby.)<br /> © Copyright by Zeresenay Alemseged/ ARCH]] | [[Image:Notcont3366.jpg|right|thumb|350px|{{#ifexist:Template:Notcont3366.jpg/credit|{{Notcont3366.jpg/credit}}<br/>|}}Selam (Lucy's Baby.)<br /> © Copyright by Zeresenay Alemseged/ ARCH]] | ||

This was the first major find by an African scientist. Zeray Alemseged was responsible for this find in Ethiopia and is equally astonishing as Lucy. This find was one of the most complete skeletons ever found, which included a scapula, and dated to around 3.31-3.35 million years old. The thyroid bone in the throat was not even fused yet which suggested a very early age of maturation (thus, the name Lucy's baby). | This was the first major find by an African scientist. Zeray Alemseged was responsible for this find in Ethiopia and is equally astonishing as Lucy. This find was one of the most complete skeletons ever found, which included a scapula, and dated to around 3.31-3.35 million years old. The thyroid bone in the throat was not even fused yet which suggested a very early age of maturation (thus, the name Lucy's baby). | ||

Like adult A. afarensis, the Dikika baby had long, curved fingers. But the fossil also brings new data to the debate in the form of two shoulder blades, or scapulae--bones previously unknown for this species. According to Alemseged, the shoulder blades of the child look most like those of a gorilla. The upward-facing shoulder socket is particularly apelike, contrasting sharply with the laterally facing socket modern humans have. This, Alemseged says, may indicate that the individual was raising its hands above its head--something primates do when they climb. | Like adult A. afarensis, the Dikika baby had long, curved fingers. But the fossil also brings new data to the debate in the form of two shoulder blades, or scapulae--bones previously unknown for this species. According to Alemseged, the shoulder blades of the child look most like those of a gorilla. The upward-facing shoulder socket is particularly apelike, contrasting sharply with the laterally facing socket modern humans have. This, Alemseged says, may indicate that the individual was raising its hands above its head--something primates do when they climb.<ref>http://www.sciam.com/article.cfm?id=special-report-lucys-baby</ref> | ||

==Physical Attributes== | ==Physical Attributes== | ||

'''Cranial''' | '''Cranial''' | ||

Although the cranium is more primitive than the Australopithecus africanus, it remains classified as a [[gracile]] Australopith instead of a chimpanzee. The hominid has a relatively small brain with an average cranial capacity of 434cc. The brain of A. afarensis was about one-third the size of the average modern human brain, or about the same size as a modern ape's brain. | Although the cranium is more primitive than the Australopithecus africanus, it remains classified as a [[gracile]] Australopith instead of a chimpanzee. The hominid has a relatively small brain with an average cranial capacity of 434cc. The brain of A. afarensis was about one-third the size of the average modern human brain, or about the same size as a modern ape's brain.<ref>http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/evolution/humans/humankind/d.html</ref> It has an [[encephalization quotient]] of 2.5 and is quite chimpanzee-like when looking at it from behind. The compound temporal neutral crests are responsible for a smaller brain capacity and its face is more prognathus when compared to the Australopithecus africanus. Males also typically had large crests (called sagital crests) on top of their skulls while females did not. <ref>http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/evolution/humans/humankind/d.html</ref><br /> | ||

Postcranially, A. afarensis provides the first evidence that, with the exception of lower limb features | Postcranially, A. afarensis provides the first evidence that, with the exception of lower limb features | ||

related to bipedalism, australopiths retained a generally apelike skeletal design and body shape(McHenry, 1991). | related to bipedalism, australopiths retained a generally apelike skeletal design and body shape(McHenry, 1991)<ref>https://melampus.colorado.edu/class/readings/4110/WoodandRichmond2000.pdf</ref> | ||

'''Dental''' | '''Dental''' | ||

| Line 33: | Line 33: | ||

The main differences between A. anamensis and A. afarensis relate to mandibular morphology and details of the dentition. The mandibular symphysis of A. anamensis is steeply-sloping compared with the more vertical symphysis of later hominids, including A. afarensis. In some respects the teeth of A. anamensis are more primitive than those of A. afarensis (e.g. | The main differences between A. anamensis and A. afarensis relate to mandibular morphology and details of the dentition. The mandibular symphysis of A. anamensis is steeply-sloping compared with the more vertical symphysis of later hominids, including A. afarensis. In some respects the teeth of A. anamensis are more primitive than those of A. afarensis (e.g. | ||

asymmetry of the premolar crowns, less posteriorlyinclined canine root, and the relatively simple crowns | asymmetry of the premolar crowns, less posteriorlyinclined canine root, and the relatively simple crowns | ||

of the deciduous first mandibular molars), but in others (e.g. the low cross-sectional profiles, and bulging sides of the molar crowns) they show similarities to more derived, and temporally much later, Paranthropus taxa. Compared with A. afarensis, A. anamensis also exhibits a primitive, horizontal tympanic | of the deciduous first mandibular molars), but in others (e.g. the low cross-sectional profiles, and bulging sides of the molar crowns) they show similarities to more derived, and temporally much later, Paranthropus taxa. Compared with A. afarensis, A. anamensis also exhibits a primitive, horizontal tympanic <ref>https://melampus.colorado.edu/class/readings/4110/WoodandRichmond2000.pdf</ref> | ||

'''Body size''' | '''Body size''' | ||

Males average a weight of 100 lbs while females average a weight of 64lbs. This indicates a significant amount of sexual dimorphism. Some studies have suggested that there exists such a great deal of dimorphism that it could in fact be two different species. This has been refuted because although body sizes differ, the morphological features are continuous. | Males average a weight of 100 lbs while females average a weight of 64lbs. This indicates a significant amount of sexual dimorphism. Some studies have suggested that there exists such a great deal of dimorphism that it could in fact be two different species. This has been refuted because although body sizes differ, the morphological features are continuous. | ||

'''Vertebrae''' | '''Vertebrae''' | ||

The vertebrae tend to have long, apelike spinous and transverse processes, and the vertebral bodies are intermediate in size compared with the ape and human conditions. Lumbar vertebrae are wedged such that the anterior length of the body is greater than the posterior length. The upper limb of A. afarensis is shorter than a great ape of comparable mass, but long relative to humans. (Jungers, 1994). | The vertebrae tend to have long, apelike spinous and transverse processes, and the vertebral bodies are intermediate in size compared with the ape and human conditions. Lumbar vertebrae are wedged such that the anterior length of the body is greater than the posterior length. The upper limb of A. afarensis is shorter than a great ape of comparable mass, but long relative to humans. (Jungers, 1994). <ref>https://melampus.colorado.edu/class/readings/4110/WoodandRichmond2000.pdf</ref> | ||

| Line 45: | Line 44: | ||

Evidence for bipedal locomotion is seen when examining the pelvis structure, knee joint and foramen magnum. The bones are strong and the pelvis is very human-like. When examining the bottom of the foot; there exists a non-opposable hallux (straight big-toe)with a longitudinal arch (for a springy foot). Although a lot of these features indicate a human-like biped, they still posses long arms, short legs and very curved fingers, which may indicate a significant amount of time in trees. <br /> | Evidence for bipedal locomotion is seen when examining the pelvis structure, knee joint and foramen magnum. The bones are strong and the pelvis is very human-like. When examining the bottom of the foot; there exists a non-opposable hallux (straight big-toe)with a longitudinal arch (for a springy foot). Although a lot of these features indicate a human-like biped, they still posses long arms, short legs and very curved fingers, which may indicate a significant amount of time in trees. <br /> | ||

Apelike morphology includes the coronal orientation of the iliac blades, a somewhat long ischium without a raised tuberosity, a reduced acetabular anterior horn, and evidence of weakly developed sacroiliac ligaments. However, the pelvis shares with humans a short, wide ilium, a well developed sciatic notch and anterior inferior iliac spine, and wide sacrum. The femoral head and acetabulum, as well as sacroiliac and lower intervertebral joints, are small relative to humans of comparable size (Jungers, 1988). This evidence for the locomotion of A. afarensis is complemented by the discovery, at Laetoli, of several trails of fossil footprints (Leakey & Hay, 1979). | Apelike morphology includes the coronal orientation of the iliac blades, a somewhat long ischium without a raised tuberosity, a reduced acetabular anterior horn, and evidence of weakly developed sacroiliac ligaments. However, the pelvis shares with humans a short, wide ilium, a well developed sciatic notch and anterior inferior iliac spine, and wide sacrum. The femoral head and acetabulum, as well as sacroiliac and lower intervertebral joints, are small relative to humans of comparable size (Jungers, 1988). This evidence for the locomotion of A. afarensis is complemented by the discovery, at Laetoli, of several trails of fossil footprints (Leakey & Hay, 1979).<ref>https://melampus.colorado.edu/class/readings/4110/WoodandRichmond2000.pdf</ref> | ||

==External Links== | ==External Links== | ||

Revision as of 16:42, 23 April 2008

Articles that lack this notice, including many Eduzendium ones, welcome your collaboration! |

Australopithecus afarensis is an extinct hominid species, which to some, is considered to be the "missing link" in human evolution. Although A. afarensis is an older species than A. africanus, it is thought to be one of the closest ancestors to the genus Homo. This is because the species shares a significant amount of traits with both chimpanzees and humans. The monumental remains known as "Lucy" stemmed from one of the most famous paleoanthropological finds in history. The potassium-argon dating found that the ancient species is thought to have lived between 3.76 and 3.49 million years ago with Lucy's remains dating to around 3.2 million years ago. The claim of discovering the potential missing link as well as the name of the species remains the subject of heated discussions within many scholarly circles. A number of scholars with Mary Leakey, in particular, would prefer the official name of this species to be Praeanthropus afarensis.

Distinguished Digs

1973: AL 129-1: Knee joint Kada Hadar, Ethiopia

Discovered in Hadar, Ethiopia by Donald Johanson, the angle of the proximal tibia and distal femur suggests a bipedal hominid. In addition, the bicondylar angle, deep patellar groove and lateral lip of the patellar groove suggest that it is in fact a hominid.

The Hadar site consists of four general members: The Basal member dates older than 3.4 million years old while the Sidi Hakum member dates to 3.22ma and is thought to be a woodland environment. The Denen Dora member dates to 3.18ma and is thought to be a forested/swampy area while the top layer is named Kada Hadar and dates to 2.3ma. The Kada Hadar member is much more open than the other bottom layers.

1974: AL 288-1: Lucy Kada Hadar, Ethiopia

The Lucy find was a singular find and relatively complete (around 40%). Discovered by the International Afar Research Expedition (IARE), Lucy became one of the most notable finds in the history of human biological evolution. Lucy's remains dated to just under 3.18 million years old. The great significance of this find is mainly due to the fact that it was the first time there existed good evidence that humans were bipedal before developing larger brains.

1978: Laetoli Site: Footprints / Holotype Tanzania

The Laetoli site is located in Tanzania and is just south of Olduvai gorge. The site was being excavated by Mary Leakey and her team in 1975 when thirteen specimens of Australopithecus afarensis were discovered, including the current holotype of Australopithecus afarensis (a mandible). When returning to the site in 1978, the team uncovered over 20,000 animal tracks which included hominid footprints. The cluster of footprints found in the tuff dates from 3.76 to 3.49 million years ago.

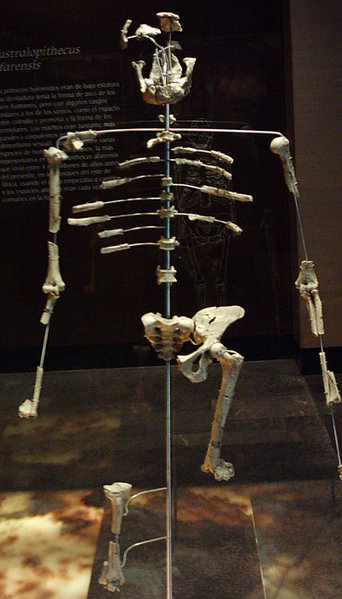

1999: Lucy's Baby Dikika, Ethiopia

This was the first major find by an African scientist. Zeray Alemseged was responsible for this find in Ethiopia and is equally astonishing as Lucy. This find was one of the most complete skeletons ever found, which included a scapula, and dated to around 3.31-3.35 million years old. The thyroid bone in the throat was not even fused yet which suggested a very early age of maturation (thus, the name Lucy's baby). Like adult A. afarensis, the Dikika baby had long, curved fingers. But the fossil also brings new data to the debate in the form of two shoulder blades, or scapulae--bones previously unknown for this species. According to Alemseged, the shoulder blades of the child look most like those of a gorilla. The upward-facing shoulder socket is particularly apelike, contrasting sharply with the laterally facing socket modern humans have. This, Alemseged says, may indicate that the individual was raising its hands above its head--something primates do when they climb.[1]

Physical Attributes

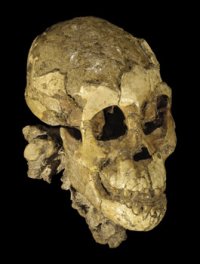

Cranial

Although the cranium is more primitive than the Australopithecus africanus, it remains classified as a gracile Australopith instead of a chimpanzee. The hominid has a relatively small brain with an average cranial capacity of 434cc. The brain of A. afarensis was about one-third the size of the average modern human brain, or about the same size as a modern ape's brain.[2] It has an encephalization quotient of 2.5 and is quite chimpanzee-like when looking at it from behind. The compound temporal neutral crests are responsible for a smaller brain capacity and its face is more prognathus when compared to the Australopithecus africanus. Males also typically had large crests (called sagital crests) on top of their skulls while females did not. [3]

Postcranially, A. afarensis provides the first evidence that, with the exception of lower limb features

related to bipedalism, australopiths retained a generally apelike skeletal design and body shape(McHenry, 1991)[4]

Dental

The canines show similar wear patterns as humans which may show a possible link between humans and Australopiths. Although the canines are a bit smaller than chimpanzees, they are bigger than other Australopiths which suggests dimorphism. There is minimal metaconid development and the cusps retain an asymmetric shape which is more chimpanzee-like. The megadontia quotient is around 1.7 and they have a shallow palate which is human-like. Although there are human-like characteristics,the tooth rows are more parallel and narrow which is more ape-like. These discrepancies show a possible link between human-like morphologies and ape-like characteristics which is both exciting and frustrating in the attempt to find a definitive answer to human evolution.

The main differences between A. anamensis and A. afarensis relate to mandibular morphology and details of the dentition. The mandibular symphysis of A. anamensis is steeply-sloping compared with the more vertical symphysis of later hominids, including A. afarensis. In some respects the teeth of A. anamensis are more primitive than those of A. afarensis (e.g. asymmetry of the premolar crowns, less posteriorlyinclined canine root, and the relatively simple crowns of the deciduous first mandibular molars), but in others (e.g. the low cross-sectional profiles, and bulging sides of the molar crowns) they show similarities to more derived, and temporally much later, Paranthropus taxa. Compared with A. afarensis, A. anamensis also exhibits a primitive, horizontal tympanic [5] Body size Males average a weight of 100 lbs while females average a weight of 64lbs. This indicates a significant amount of sexual dimorphism. Some studies have suggested that there exists such a great deal of dimorphism that it could in fact be two different species. This has been refuted because although body sizes differ, the morphological features are continuous.

Vertebrae The vertebrae tend to have long, apelike spinous and transverse processes, and the vertebral bodies are intermediate in size compared with the ape and human conditions. Lumbar vertebrae are wedged such that the anterior length of the body is greater than the posterior length. The upper limb of A. afarensis is shorter than a great ape of comparable mass, but long relative to humans. (Jungers, 1994). [6]

Perlvis: bipedal locomotion

Evidence for bipedal locomotion is seen when examining the pelvis structure, knee joint and foramen magnum. The bones are strong and the pelvis is very human-like. When examining the bottom of the foot; there exists a non-opposable hallux (straight big-toe)with a longitudinal arch (for a springy foot). Although a lot of these features indicate a human-like biped, they still posses long arms, short legs and very curved fingers, which may indicate a significant amount of time in trees.

Apelike morphology includes the coronal orientation of the iliac blades, a somewhat long ischium without a raised tuberosity, a reduced acetabular anterior horn, and evidence of weakly developed sacroiliac ligaments. However, the pelvis shares with humans a short, wide ilium, a well developed sciatic notch and anterior inferior iliac spine, and wide sacrum. The femoral head and acetabulum, as well as sacroiliac and lower intervertebral joints, are small relative to humans of comparable size (Jungers, 1988). This evidence for the locomotion of A. afarensis is complemented by the discovery, at Laetoli, of several trails of fossil footprints (Leakey & Hay, 1979).[7]

External Links

References

- ↑ http://www.sciam.com/article.cfm?id=special-report-lucys-baby

- ↑ http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/evolution/humans/humankind/d.html

- ↑ http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/evolution/humans/humankind/d.html

- ↑ https://melampus.colorado.edu/class/readings/4110/WoodandRichmond2000.pdf

- ↑ https://melampus.colorado.edu/class/readings/4110/WoodandRichmond2000.pdf

- ↑ https://melampus.colorado.edu/class/readings/4110/WoodandRichmond2000.pdf

- ↑ https://melampus.colorado.edu/class/readings/4110/WoodandRichmond2000.pdf

(1) http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/evolution/humans/humankind/d.html (2) http://www.sciam.com/article.cfm?id=special-report-lucys-baby (3) https://melampus.colorado.edu/class/readings/4110/WoodandRichmond2000.pdf