Luftwaffe: Difference between revisions

imported>Richard Jensen m (add details) |

imported>Howard C. Berkowitz (Kammhuber line, more links for electronics) |

||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

==Battle of Britain== | ==Battle of Britain== | ||

In the [[Battle of Britain]], the British surprised the Germans with their high quality airplanes; flying from home bases and using [[radar]] as part of an [[integrated air defense system]] (IADS), they had a significant advantage. The Hawker Hurricane fighter plane played a vital role for the Royal Air Force (RAF) in winning the Battle of Britain in the summer of 1940. A fast, heavily armed monoplane that went into service in 1937, the Hurricane was effective against both German fighters and bombers and accounted for 70-75% of German losses during the battle. The Germans immediately pulled out their Stukas, which were so slow they were child's play for the Hurricanes and Spitfires. | |||

===Navigation=== | ===Navigation=== | ||

The first system of radio guidance used by the Luftwaffe was the Knickebein or System K, operational in 1938. With it, ground controllers could direct bombers to targets at night and in all kinds of weather. Thirteen Knickebein transmitters were eventually built in the west, six in France. System K was expanded by the addition of X-Gerät, a system of automatic bombardment. This was followed by System Y-Gerät (Wotan II). British countermeasures forced the Germans to discontinue the offensive use of the system but they used the Y-Gerät until the invasion of Normandy. Over friendly territory the Germans used grid and hyperbolic systems, copied partly from the English Ground Electronic Environment and from LORAN. After 1941, the Luftwaffe used a new system for offensive navigation known as the Bernard system, which gave the airplane the transmitter's call-sign, the bearing of the plane, and the position, altitude, and heading of an enemy interceptor. In 1942 the Germans copied the English IFF, calling it the EGON system, which was also used offensively for tactical guidance. After the war, much German radio-navigation technology was adopted for military and civilian purposes.<ref>Jean-François Salles, "Organisation des Systemes de Radionavigation de la Luftwaffe en Normandie en 1944," [The Organization of the Radio Navigation Systems of the Luftwaffe in Normandy in 1944]. ''Revue Historique des Armées'' 1995 (1): 77-88. Issn: 0035-3299 </ref> | The first system of radio guidance used by the Luftwaffe was the Knickebein or System K, operational in 1938. With it, ground controllers could direct bombers to targets at night and in all kinds of weather. Thirteen [[Knickebein]] transmitters were eventually built in the west, six in France. System K was expanded by the addition of [[X-Gerät]], a system of automatic bombardment. This was followed by System [[Y-Gerät]] (Wotan II). British countermeasures forced the Germans to discontinue the offensive use of the system but they used the Y-Gerät until the invasion of Normandy. | ||

Over friendly territory the Germans used grid and hyperbolic systems, copied partly from the English Ground Electronic Environment and from [[LORAN]]. After 1941, the Luftwaffe used a new system for offensive navigation known as the Bernard system, which gave the airplane the transmitter's call-sign, the bearing of the plane, and the position, altitude, and heading of an enemy interceptor. In 1942 the Germans copied the English [identification-friend-or-foe]] (IFF), calling it the EGON system, which was also used offensively for tactical guidance. | |||

After the war, much German radio-navigation technology was adopted for military and civilian purposes.<ref>Jean-François Salles, "Organisation des Systemes de Radionavigation de la Luftwaffe en Normandie en 1944," [The Organization of the Radio Navigation Systems of the Luftwaffe in Normandy in 1944]. ''Revue Historique des Armées'' 1995 (1): 77-88. Issn: 0035-3299 </ref> | |||

===Stopping the bombers=== | ===Stopping the bombers=== | ||

The climax in air war came in February 1944, when the Luftwaffe made a powerful effort to sweep American day bombers from the skies. The battle raged for a week. It was fought over Regensburg, Merseburg, Schweinfurt, and other critical industrial centers. The German fighter force was severely crippled. | While the British IADS was operational in the critical days of 1940, the Germans were beginning to build their IADS, the [[Kammhuber Line]], in 1940. | ||

The climax in the air war came in February 1944, when the Luftwaffe made a powerful effort to sweep American day bombers from the skies. The battle raged for a week. It was fought over Regensburg, Merseburg, Schweinfurt, and other critical industrial centers. The German fighter force was severely crippled. | |||

The American response was the "Big Week," (20-25 February 1944), when the US 8th Air Force launched a full-scale assault against the German aircraft industry. The purpose was to diminish the German air force by cutting into its fighter-plane production and by drawing the German fighters into the air for American fighters to destroy. Big Week raids inflicted serious losses on the German air force and went far toward achieving the air superiority over Western Europe that made certain the Allied success in the D-Day invasion of France in June 1944. By the late spring of 1944, synthetic fuel plants and crude oil refineries became the prime targets for Allied bombers, which reduced production between May and October 1944 to 5% of the former monthly output. | The American response was the "Big Week," (20-25 February 1944), when the US [[8th Air Force]] launched a full-scale assault against the German aircraft industry. The purpose was to diminish the German air force by cutting into its fighter-plane production and by drawing the German fighters into the air for American fighters to destroy. Big Week raids inflicted serious losses on the German air force and went far toward achieving the air superiority over Western Europe that made certain the Allied success in the D-Day invasion of France in June 1944. By the late spring of 1944, synthetic fuel plants and crude oil refineries became the prime targets for Allied bombers, which reduced production between May and October 1944 to 5% of the former monthly output. | ||

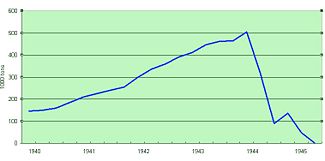

[[Image:German-aviation-gas-ww2.jpg|thumb|325px|Germany's supply of aviation gasoline 1940-45]] | [[Image:German-aviation-gas-ww2.jpg|thumb|325px|Germany's supply of aviation gasoline 1940-45]] | ||

Revision as of 23:02, 25 June 2008

The Luftwaffe was the German Air Force, 1933-45.

1930s

In 1925 the Soviet Union allowed the German government set up the top-secret Lipetsk Aviation School, inside Russia, to train pilots and navigators in violation of the Versailles Treaty of 1919, which ordered that Germany could never have an air force. The school closed in 1933 when secrecy was no longer needed to defy Versailles.

Various proposals to centralize military aviation under a separate military service, beginning even before World War I, were thwarted by the usual army-navy differences and the internal opposition of each service to losing its subordinate air arm. Air power theories alone would not have gained independence for the German air force, but Hitler's foreign policy needs and the political power of air minister Hermann Goering within the Nazi party proved a key in gaining first separate status under an Air Ministry and then gaining increased power, such as in acquiring control of antiaircraft artillery.

Strategic and tactical doctrines

In the 1930s Hans von Seeckt and senior army leadership, using World War I as a guide, advocated an independent air force designed for aggressive interdiction, close air support, and air-to-air warfare. Developed and written by airmen and army officers and published as "Conduct of the Air War" in 1935, the Luftwaffe's operational doctrine was battle-tested in the Spanish Civil War.[1]

The Spanish Civil War (1936-38) was the most intensive experience of combat for the Luftwaffe before World War II. Germany sent its "Kondor Legion" to test out its "blitzkrieg" doctrine using the Junkers Ju-87 Stuka dive-bomber. In addition they completely redesigned their air superiority fighter tactics, and discovered new techniques for high-speed dogfight tactics and tactical air support for ground forces. The Spanish Civil War had a tremendous impact on all aspects of Luftwaffe combat doctrine, giving it technique, doctrine and self confidence that Britain and France lacked.[2]

The Spanish war demonstrated the effectiveness of logistical disruption and ground attack support, and confirmed German views concerning the ineffectiveness - and even counterproductive nature - of the strategic bombing of civilian populations. A common misperception holds that the Luftwaffe was primarily a tactical support force for the army and that, unlike the American and British air forces, it did not develop a theory or concept of strategic air war. In reality, the Luftwaffe built up an extensive doctrine of strategic air war by 1939. In the 1930s imaginative Nazis saw strategic bombardment by air as a powerful tool. Air warfare was seen as a growing threat to Germany, especially in British hands, so the Luftwaffe became a means of national mobilization and redemption. Nazi Germany believed that air warfare would allow the country to rebuild itself in a racial compact. During World War II, are warfare became a means for rejuvenating authority domestically and increasing influence abroad. However, Germany never built long-range bombers; only the British and Americans did so. Moreover, the Luftwaffe used its aircraft in a strategic manner in the early campaigns in Poland and France in 1939-40. As the war progressed, however, the Luftwaffe failed to mount a major strategic air campaign, not because of the lack of strategic air doctrine or theory but because of the failure to produce an effective heavy bomber, the failure to train enough pilots for a war of attrition, and the failure of the high command to utilize the Luftwaffe in the most effective manner. [3]

Between 1918 and 1939 the Luftwaffe steadily developed an army support aviation doctrine (close air support of ground forces or CAS) that, while not its primary mission, nevertheless influenced its organization and aircraft design procurement. After 1939, it further refined the doctrine based on successful operational experience, and by the time of the German invasion of Russia in 1941 the Luftwaffe was directly and decisively supporting army operations. In contrast, the Americans and British showed little interest in army support during the interwar period, and as late as 1940, notwithstanding the German success in Poland in 1939, the RAF still possessed no air formation that could rapidly respond to the ground situation.[4]

French despair

The French air force intelligence section was relatively well informed on the growth of the Luftwaffe, which, in their view, was the most important of the three services of the German armed forces and which could call upon virtually unlimited resources. The new German pursuit planes and bombers were considered the best in the world; German aircraft production was estimated at one thousand per month at the time of the Munich crisis. Thus, German aerial superiority was the main argument against protecting Czechoslovakia from Nazi aggression. The subsequent French rearmament program greatly increased aircraft production, but it failed to keep pace with German increases. Guy La Chambre, the French air minister, optimistically informed the government that the air force was capable of dealing with the Luftwaffe. On the other hand, General Joseph Vuillemin, air force chief of staff, described the French air force as far inferior and consistently opposed war with Germany. Nevertheless, the Daladier government, believing that the rearmament program would soon take off and relying on British determination to stop Hitler, rejected any new policy of appeasement. The reorganization of the air force had not been completed when the war broke out and the German aircraft industry was able to achieve a spectacular increase in production due to the development of machine tools more efficient than those used in French factories. Even so the Germans were not so far ahead in 1940. They were aghead in morale and self-confidence, as France lost the aerial battle of 1940 in the minds of the leaders of the air force rather than on the floors of the aircraft factories.[5]

Aircraft

Wartime production

Production in the early years of the war was small, primarily because Luftwaffe did not see a need for a vast armada. At one point General Jeschonneck, chief of the air staff, opposed a suggested increase in fighter plane production with the remark that he wouldn't know what to do with a monthly production of more than 360 fighters. By late 1943 doom was in the air and plans called for a steadily increasing output of fighters. By 1944 Allied bombers targeted aircraft factories, but they were widely dispersed. The main way to stop the Luftwaffe was to cut off its gasoline by bombing refineries and synthetic oil plants, and for the Soviets to capture the Romanian oil fields.

Luftwaffe Field Marshal Erhard Milch and airplane designer Ernst Heinkel built a huge factory at Budzyn, Poland, called the "Ultra Project" designed to use Jews as slave laborers to build warplanes. It lasted 18 months but turned out not one aircraft nor a single aircraft part.[6]

War in the West

Battle of Britain

In the Battle of Britain, the British surprised the Germans with their high quality airplanes; flying from home bases and using radar as part of an integrated air defense system (IADS), they had a significant advantage. The Hawker Hurricane fighter plane played a vital role for the Royal Air Force (RAF) in winning the Battle of Britain in the summer of 1940. A fast, heavily armed monoplane that went into service in 1937, the Hurricane was effective against both German fighters and bombers and accounted for 70-75% of German losses during the battle. The Germans immediately pulled out their Stukas, which were so slow they were child's play for the Hurricanes and Spitfires.

The first system of radio guidance used by the Luftwaffe was the Knickebein or System K, operational in 1938. With it, ground controllers could direct bombers to targets at night and in all kinds of weather. Thirteen Knickebein transmitters were eventually built in the west, six in France. System K was expanded by the addition of X-Gerät, a system of automatic bombardment. This was followed by System Y-Gerät (Wotan II). British countermeasures forced the Germans to discontinue the offensive use of the system but they used the Y-Gerät until the invasion of Normandy.

Over friendly territory the Germans used grid and hyperbolic systems, copied partly from the English Ground Electronic Environment and from LORAN. After 1941, the Luftwaffe used a new system for offensive navigation known as the Bernard system, which gave the airplane the transmitter's call-sign, the bearing of the plane, and the position, altitude, and heading of an enemy interceptor. In 1942 the Germans copied the English [identification-friend-or-foe]] (IFF), calling it the EGON system, which was also used offensively for tactical guidance.

After the war, much German radio-navigation technology was adopted for military and civilian purposes.[7]

Stopping the bombers

While the British IADS was operational in the critical days of 1940, the Germans were beginning to build their IADS, the Kammhuber Line, in 1940.

The climax in the air war came in February 1944, when the Luftwaffe made a powerful effort to sweep American day bombers from the skies. The battle raged for a week. It was fought over Regensburg, Merseburg, Schweinfurt, and other critical industrial centers. The German fighter force was severely crippled.

The American response was the "Big Week," (20-25 February 1944), when the US 8th Air Force launched a full-scale assault against the German aircraft industry. The purpose was to diminish the German air force by cutting into its fighter-plane production and by drawing the German fighters into the air for American fighters to destroy. Big Week raids inflicted serious losses on the German air force and went far toward achieving the air superiority over Western Europe that made certain the Allied success in the D-Day invasion of France in June 1944. By the late spring of 1944, synthetic fuel plants and crude oil refineries became the prime targets for Allied bombers, which reduced production between May and October 1944 to 5% of the former monthly output.

Allied medium bombers and fighter-bombers struck Luftwaffe airfields in diversionary attacks so timed as to reduce the concentration of fighters that threatened the bomber formations. Diversionary fighter sweeps further dislocated the Luftwaffe. As the range of P-47 and P-51 fighters was increased through the installation of additional fuel tanks, they were employed more and more to escort bombers to targets deep in Germany. In response the Luftwaffe withdraw fighters from the East to meet the threat from the West. This was an important factor in enabling the Soviet air forces to maintain air superiority on their front.

War in the East

Though victorious in Poland in September, 1939, the Luftwaffe did not perform as well as the Nazi propaganda machine led the world to believe, both because of its own internal weaknesses and the creditable resistance put up by the Polish air force.[8]

On the first day of the Nazi attack on the Soviet Union in 1941, the Soviet air force (VVS) lost 336 aircraft in aerial combat to only 40 German losses. Much more threatening was the loss, within a few days of 800 Soviet aircraft destroyed on the ground in the course of Luftwaffe bombing raids on airfields. This was the first ever instance of one air force achieving a significant victory over another by pre-emptive strikes against its air bases. The Luftwaffe had attempted this in Poland in 1939 and in France in 1940 without much luck. The successful attacks on Soviet air bases, the superiority of the Luftwaffe pilots in air-to-air combat, and the loss of hundreds of damaged but repairable aircraft that had to be abandoned on airfields about to be over-run by advancing German ground troops together meant that, by the end of the first week of the German invasion, the VVS was nearly defunct as a combat organization.

In May 1942, the Luftwaffe, by providing a high level of tactical air support, played a key role in smashing a major Soviet offensive around Kharkov. Performing well in all operations, including tactical reconnaissance, air-drop and supply, direct battlefield support, interdiction, and protection of German logistics, it initially engaged in a series of nonstop defensive missions that countered the Soviet effort to encircle German forces and then greatly aided German ground forces as they threw back and crushed the Soviet forces.[9]

In August and September 1942 the Luftwaffe had the opportunity and planes to deliver a major blow against the Soviet economy by attacking the Caucasus oil centers that provided nearly all of the Soviet supplies. Instead, Hitler diverted his airpower against Stalingrad, By October 1942, when Hitler finally ordered air attacks against the oil centers, but the Germans no longer had the bomber strength and advanced forward bases to carry out major operations against them. The raids were too little and too late and proved incapable of crippling Soviet oil production.[10]

In July 1942, north of Norway, an attack by the Luftwaffe sank two ships, and convoy PQ-17, sailing from Iceland to Archangel, Russia, was ordered to scatter by the British Admiralty. It mistakenly thought the German battleship Tirpitz was about to intercept the convoy. Twenty-two more ships were sunk by the well-coordinated attack of German air forces.[11]

After 1942 the Soviets completely restructured their air force around mobile air armies. By 1942-3 Soviet air power challenged the Luftwaffe for air supremacy in the Stalingrad, Kuban, and Kursk campaigns. Frontal aviation's 17 air armies were complemented by a long-range air army in 1944, by which time the Soviets had air superiority, though it lacked long range bombers.

Failure of Cooperation

Germany's Kriegsmarine (navy) and Luftwaffe failed to cooperate throughout most of the war because of interbranch jealousy, limited strategic vision, poor leadership in the Luftwaffe, and the personality defects of Göring. This failure, coupled with the strategic shift eastward after mid-1941 and the lack of an offensive oriented air branch of the Kriegsmarine, meant that Germany was never able to fulfill its potential effectiveness in naval operations designed to restrict Britain's operational and material resource base.[12]

In sharp contrast to the smooth cooperation of the Allies, the Luftwaffe ignored opportunities for strategic and economic cooperation with the air forces of its allies Italy, Finland, Romania, and Hungary. Instead of using factories in France, the Netherlands and Czechoslovakia to build new air fleets, it removed the machinery and shut the factories.[13]

Collapse

By 1942 everything started to go wrong. Defeat after defeat in the air against increasingly superior enemy planes sapped morale, and killed off the best pilots. Goering was easily outmaneuvered by rival Nazis after 1940 and the Luftwaffe experienced an erosion of authority after it failed to meet his grandiose promises. Hitler was enthusiastic in support, but remained ignorant of air affairs, even though he talked glibly about them. He did not coordinate the Luftwaffe with the other branches of service. He did not plan in terms of continuous massive quantity and quality in the number of planes or in their offensive use. He thought in terms of defense or of secret, magic weapons for one massive, catastrophic blow.[14] Luftwaffe technology was not well concentrated. The Me 262 jet flew test runs in 1939--Germany needed 10,000 of these superior planes byt only produced 1000 and most never flew in combat. The brilliant engineering efforts that went into the highly innovative V-1 jet-based missile were wasted from a military point of view. The success of blitzkrieg blinded the Germans to the nevcessity of planning for a protracted air war, so they lacked the planes, fuel suypplies, and trained airmen. By 1944 their pilots had far less flying experience than the Allies, and were more and more helpless in the sky. Furthermore, the Luftwaffe was unable to solve its growing logistics problems; when its fuel supply ran dry in 1944 it was doomed. Increasingly the Luftwaffe concentrated on ground-based anti-aircraft operations, which involved hundreds of thousands of women soldiers. Surplus airmen and ground crews were reorganized into infantry units (under Luftwaffe command.) [15]

Bibliography

- British Air Ministry. Rise and Fall of the German Air Force (1948, 1969), excellent official British history

- Claasen, Adam R. A.Hitler's Northern War: The Luftwaffe's Ill-Fated Campaign, 1940-1945. (2001). 338 pp.

- Corum, James S. and Muller, Richard R. The Luftwaffe's Way of War: German Air Force Doctrine, 1911-1945. (1998). 295 pp.

- Corum, James S. The Luftwaffe: Creating the Operational Air War, 1918-1940. (1997). 368 pp.

- Harvey, A.D. "The Soviet Air Force versus the Luftwaffe: History Today. 52#1 (January 2002) pp 48+ in EBSCO and online edition

- Griehl, Manfred. Luftwaffe over America: The Secret Plans to Bomb the United States in World War II. (2004). 256 pp.

- Hayward, Joel. Stopped at Stalingrad: The Luftwaffe and Hitler's Defeat in the East, 1942-1943 (2001) excerpt and text search

- Macksey, Kenneth. Kesselring: The Making of the Luftwaffe. (1979). 262 pp.

- Mitcham, Samuel W. Men of the Luftwaffe. (1988). 356 pp.

- Murray, Williamson. Luftwaffe: Strategy for Defeat, 1933-1945 (1985), the standard scholarly history excerpt and text search

- Overy, Richard J. The Air War, 1939-1945 (1981), sophisticated interpretation of all major powers

- Overy, Richard. Goering (1984) excerpt and text search

- Overy, Richard. The Battle of Britain: The Myth and the Reality (2002) excerpt and text search

- Proctor, Raymond L. Hitler's Luftwaffe in the Spanish Civil War. (1983). 289 pp.

- Spick, Mike. Luftwaffe Fighter Aces: the Jagdflieger and their Combat Tactics and Techniques (1996);

- Wark, Wesley K. "British Intelligence on the German Air Force and Aircraft Industry, 1933-1939." Historical Journal 1982 25(3): 627-648. Issn: 0018-246x in Jstor

Primary Sources

- Galland, Adolf. The First and the Last: German Fighter Forces in World War II (1955)

- Orange, Vincent. "The German Air Force Is Already 'The Most Powerful in Europe': Two Royal Air Force Officers Report on a Visit to Germany, 6-15 October 1936." Journal of Military History 2006 70(4): 1011-1028. Issn: 0899-3718 Fulltext: Ebsco

See also

Online resources

notes

- ↑ James S. Corum, "From Biplanes to Blitzkrieg: the Development of German Air Doctrine Between the Wars." War in History 1996 3(1): 85-101. Issn: 0968-3445

- ↑ Christopher C. Locksley, Condor over Spain: the Civil War, Combat Experience and the Development of Luftwaffe Airpower Doctrine." Civil Wars 1999 2(1): 69-99. Issn: 1369-8249

- ↑ Peter Fritzsche, "Machine Dreams: Airmindedness and the Reinvention of Germany." American Historical Review, 98 (June 1993): 685-710; James S. Corum, "The Development of Strategic Air War Concepts in Interwar Germany, 1919-1939." Air Power History 1997 44(4): 18-35. Issn: 1044-016x

- ↑ James S. Corum, "The Luftwaffe's Army Support Doctrine, 1918-1941." Journal of Military History 1995 59(1): 53-76. Issn: 0899-3718 in Jstor

- ↑ Peter Jackson, "La Perception De La Puissance Aerienne Allemande et Son Influence sur la Politique Exterieure Française Pendant Les Crises Internationales de 1938 a 1939," [The Perception of German Air Power and its Influence on French Foreign Policy During the International Crises of 1938-39]. Revue Historique des Armées 1994 (4): 76-87. Issn: 0035-3299; Faris R. Kirkland, "French Air Strength in May 1940." Air Power History 1993 40(1): 22-34. Issn: 1044-016x

- ↑ Lutz Budrass, "'Arbeitskräfte Können Aus Der Reichlich Vorhandenen Jüdischen Bevölkerung Gewonnen Werden.' Das Heinkel-werk in Budzyn 1942-1944," Jahrbuch Für Wirtschaftsgeschichte 2004 (1): 41-64. Issn: 0075-2800

- ↑ Jean-François Salles, "Organisation des Systemes de Radionavigation de la Luftwaffe en Normandie en 1944," [The Organization of the Radio Navigation Systems of the Luftwaffe in Normandy in 1944]. Revue Historique des Armées 1995 (1): 77-88. Issn: 0035-3299

- ↑ John F. Kreis, "Blitzkrieg in Poland." Air Power History 1989 36(3): 31-35. Issn: 1044-016x

- ↑ Joel S. A. Hayward, "The German Use of Air Power at Kharkov, May 1942." Air Power History 1997 44(2): 18-29. Issn: 1044-016x

- ↑ Joel Hayward, "Too Little, Too Late: an Analysis of Hitler's Failure in August 1942 to Damage Soviet Oil Production." Journal of Military History 2000 64(3): 769-794. Issn: 0899-3718 in Jstor

- ↑ Harold J. McCormick, "Convoy Catastrophe: the Destruction of Pq-17 to North Russia in July, 1942." Sea History 1992 (62): 14-16. Issn: 0146-9312

- ↑ Sönke Neitzel, "Kriegsmarine and Luftwaffe Co-operation in the War Against Britain, 1939-1945." War in History 2003 10(4): 448-463. Issn: 0968-3445 Fulltext: Ebsco

- ↑ James S. Corum, "The Luftwaffe and its Allied Air Forces in World War Ii: Parallel War and the Failure of Strategic and Economic Cooperation." Air Power History 2004 51(2): 4-19. Issn: 1044-016x Fulltext: Ebsco

- ↑ R. J. Overy, "Hitler and Air Strategy," Journal of Contemporary History 1980 15(3): 405-421. Issn: 0022-0094 in Jstor

- ↑ Horst Boog, "Luftwaffe and Logistics in the Second World War." Aerospace Historian 1988 35(2): 103-110. Issn: 0001-9364