Feedback: Difference between revisions

imported>John R. Brews (change lead sentence) |

imported>John R. Brews (types) |

||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

Unlike ''feedforward'' control, which anticipates a need for change, ''feedback'' introduces change only as a response to a change in behavior.<ref name=Seborg/> | Unlike ''feedforward'' control, which anticipates a need for change, ''feedback'' introduces change only as a response to a change in behavior.<ref name=Seborg/> | ||

Feedback typically is seen as ''negative'' or ''positive'', and in control theory ''negative feedback'' is any form of feedback in which a change in system behavior causes the feedback to ''oppose'' that change, while ''positive feedback'' tends to augment the change. In biology, the term ''bipolar feedback'' sometimes is used to describe interacting systems, where the output of some systems affect the input of others, and vice versa.<ref name=Smit/> | |||

==Examples== | ==Examples== | ||

Revision as of 11:05, 1 August 2014

Feedback is the use of information from the monitoring of system performance either to modify or to maintain that performance.

- "Feedback is the use of a measurement of some aspect of system behavior to correct or adjust that behavior."[1]

Unlike feedforward control, which anticipates a need for change, feedback introduces change only as a response to a change in behavior.[2]

Feedback typically is seen as negative or positive, and in control theory negative feedback is any form of feedback in which a change in system behavior causes the feedback to oppose that change, while positive feedback tends to augment the change. In biology, the term bipolar feedback sometimes is used to describe interacting systems, where the output of some systems affect the input of others, and vice versa.[3]

Examples

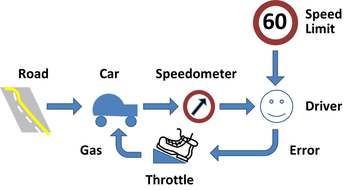

An everyday example of negative feedback to control a system is shown at the left, where a car is maintained at the speed limit by a driver using the throttle (accelerator) to adjust to road conditions (for example, curves or grades). The car's speed is decided by a combination of the road conditions and the gas supplied. The gas supplied is the system feedback, the amount of which is controlled by the driver who compares the speedometer reading with the speed limit and reduces the error.

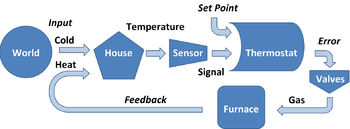

A more formal example of negative feedback is the thermostatic control of house temperature.[4] In the figure, the house temperature is a response to the combined heat input from the world and from the furnace. Suppose a change occurs in the heat supplied to the house by the outside world. The resultant house temperature is sensed by a thermometer and converted to an electrical signal. This signal is compared by the thermostat to a set-point signal that corresponds to the desired temperature value. The discrepancy between the set point and the signal is calculated as an error signal by the thermostat, activating the valves regulating gas to the furnace. Depending upon the sign of the error the furnace produces more or less heat, regulating the combined heat input to the house so the temperature stays constant. In other words, the information on system temperature is used to generate feedback that keeps the temperature at value.

It might be noted that translation of signals between various forms (such as temperature, chemical signals, electrical signals, mechanical signals) occurs throughout the feedback loop. Also, there are time delays introduced at each step in a feedback loop that affect its success in tracking variations in the world's input.

The same principle is found in biology as homeostasis.[5]

Terminology

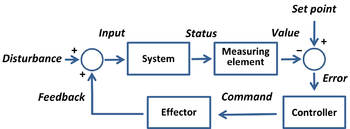

To discuss the general example, some formal terminology that does not depend upon the specific system is useful.[6]

- Control variable: The monitored parameter used to determine the system status; for example, speed of the car or temperature of the house.

- Measured variable: The translated form of the control variable as output from a sensor; for example, the speedometer reading of vehicle speed, or the thermometer reading corresponding to house temperature.

- Set point: The value of the measured variable that is considered desirable.

- Error: The discrepancy between the measured and set-point values as calculated by a controller; for example, the driver's observation of the discrepancy between speed and speed limit, or the output of the thermostat.

- Manipulated variable: The feedback variable to the system; for example the throttle position controlling gasoline input to the car or the gas valve position controlling fuel input to the furnace.

- Load variable: The environmental input affecting the system; for example the grade of the road or the heat from the sun.

- Controller: The mechanism that detects the discrepancy between the set point and the measured variable indicating system status and signals for action.

- Sensor (Measuring element): The mechanism used to translate the system status to a variable understood by the controller.

- Effector (Actuator): The mechanism supplying the feedback response to the system. In part, the carburetor and fuel supply system in the car, or the furnace in the house.

- Receptor: The part of the system subject to disturbance and to control.

Diagrams that are rearrangements of the block diagram above are found in many sources.[7][8]

References

- ↑ Mario Lucertini, Ana Millàn Gasca, Fernando Nicolò (2004). Technological Concepts and Mathematical Models in the Evolution of Modern Engineering Systems: Controlling, Managing, Organizing. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9783764369408.

- ↑ Dale E. Seborg, Duncan A. Mellichamp, Thomas F. Edgar, Francis J. Doyle, III (2010). “§15.1 Introduction to feedforward control”, Process Dynamics and Control. John Wiley & Sons, pp. 274 ff. ISBN 9780470128671.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedSmit - ↑ Rao Ganesh (2010). “Feedback control”, Control engineering. Pearson Education India, pp. 29 ff. ISBN 9788131732335.

- ↑ See, for example, Lauralee Sherwood (2005). Fundamentals of Physiology: A Human Perspective, 3rd ed. Cengage Learning, p. 14. ISBN 9780534466978.

- ↑ Sudheer S Bhagade, Govind Das Nageshwar (2011). “Control terminology”, Process Dynamics and Control. PHI Learning Private Limited, pp. 3 ff. ISBN 9788120344051.

- ↑ Sudheer S Bhagade, Govind Das Nageshwar (2011). “Control terminology”, Process Dynamics and Control. PHI Learning Private Limited, p. 9. ISBN 9788120344051.

- ↑ See Figure 3.31 (b) in SK Singh (2009). Process Control: Concepts Dynamics And Applications. PHI Learning Private Ltd., p. 222. ISBN 978812033678.