Catalytic reforming/Citable Version: Difference between revisions

Pat Palmer (talk | contribs) |

John Leach (talk | contribs) m (Text replacement - "Aluminum" to "Aluminium") |

||

| Line 113: | Line 113: | ||

==Catalysts and mechanisms== | ==Catalysts and mechanisms== | ||

Most catalytic reforming catalysts contain platinum or rhenium on a [[Silicon dioxide|silica]] or silica-[[ | Most catalytic reforming catalysts contain platinum or rhenium on a [[Silicon dioxide|silica]] or silica-[[Aluminium oxide|alumina]] support base, and some contain both platinum and rhenium. Fresh catalyst is [[chloride|chlorided]] (chlorinated) prior to use. | ||

The noble metals (platinum and rhenium) are considered to be catalytic sites for the dehydrogenation reactions and the chlorinated alumina provides the [[acid]] sites needed for isomerization, cyclization and hydrocracking reactions.<ref name=Gary/> | The noble metals (platinum and rhenium) are considered to be catalytic sites for the dehydrogenation reactions and the chlorinated alumina provides the [[acid]] sites needed for isomerization, cyclization and hydrocracking reactions.<ref name=Gary/> | ||

Revision as of 07:35, 6 March 2024

Catalytic reforming is a catalytic chemical process used in petroleum refineries to convert naphthas, typically having low octane ratings, into high-octane liquid products called reformates which are components of high-octane gasoline (also known as petrol).[1][2][3][4] Basically, the process re-arranges or re-structures the hydrocarbon molecules in the naphtha feedstocks as well as breaking some of the molecules into smaller molecules. The overall effect is that the product reformate contains hydrocarbons with more complex molecular shapes having higher octane values than the hydrocarbons in the naphtha feedstock. In so doing, the process separates hydrogen molecules from the hydrocarbon molecules and produces very significant amounts of byproduct hydrogen gas for use in a number of the other processes involved in a modern petroleum processing refinery. Other byproducts are small amounts of methane, ethane, propane and butanes.

This process is quite different from and not to be confused with the catalytic steam reformer process used industrially to produce various products such as hydrogen, ammonia and methanol from natural gas, naphtha or other petroleum-derived feedstocks. Nor is this process to be confused with various other catalytic reforming processes that use methanol or biomass-derived feedstocks to produce hydrogen for fuel cells or other uses.

History

Universal Oil Products (also known as UOP) is a multi-national company developing and delivering technology to the petroleum refining, natural gas processing, petrochemical production and other manufacturing industries. In the 1940s, an eminent research chemist named Vladimir Haensel[5] working for UOP developed a catalytic reforming process using a catalyst containing platinum. Haensel's process was subsequently commercialized by UOP in 1949 for producing a high octane gasoline from low octane naphthas and the UOP process became known as the Platforming process.[6] The first Platforming unit was built in 1949 at the refinery of the Old Dutch Refining Company in Muskegon, Michigan.

In the years since then, many other versions of the process have been developed by some of the major oil companies and other organizations. Today, the large majority of gasoline produced worldwide is derived from the catalytic reforming process.

To name a few of the other catalytic reforming versions that were developed, all of which utilized a platinum and/or a rhenium catalyst:

- Rheniforming: Developed by Chevron Oil Company.

- Powerforming: Developed by Esso Oil Company, now known as ExxonMobil.

- Magnaforming: Developed by Engelhard Catalyst Company and Atlantic Richfield Oil Company (ARCO).

- Ultraforming: Developed by Standard Oil of Indiana, now a part of the British Petroleum Company.

- Houdriforming: Developed by the Houdry Process Corporation.

- CCR Platforming: A Platforming version, designed for continuous catalyst regeneration, developed by UOP.

- Octanizing: A catalytic reforming version developed by Axens, a subsidiary of Institut Français du Petrole (IFP), designed for continuous catalyst regeneration.

Chemistry

Before describing the reaction chemistry of the catalytic reforming process as used in petroleum refineries, the typical naphthas used as catalytic reforming feedstocks will be discussed.

Typical naphtha feedstocks

A petroleum refinery includes many unit processes and unit operations. The first unit process in a refinery is the crude oil distillation unit. The overhead liquid distillate from that unit is called naphtha and will become a major component of the refinery's gasoline (petrol) product after it is further processed through a catalytic hydrodesulfurizer to remove sulfur-containing hydrocarbons and a catalytic reformer to reform its hydrocarbon molecules into more complex molecules with a higher octane rating value. The naphtha is a mixture of very many different hydrocarbon compounds. It has an initial boiling point of about 35 °C and a final boiling point of about 200 °C, and it contains paraffin, naphthene (cyclic paraffins) and aromatic hydrocarbons ranging from those containing 4 carbon atoms to those containing about 10 or 11 carbon atoms.

The naphtha from the crude oil distillation is often further distilled to produce a "light" naphtha containing most (but not all) of the hydrocarbons with 6 or less carbon atoms and a "heavy" naphtha (i.e., dehexanized naphtha) containing most (but not all) of the hydrocarbons with more than 6 carbon atoms. The heavy naphtha has an initial boiling point of about 140 to 150 °C and a final boiling point of about 190 to 205 °C. The naphthas derived from the distillation of crude oils are referred to as "straight-run" naphthas.

It is the straight-run heavy naphtha that is usually processed in a catalytic reformer because the light naphtha has molecules with 6 or less carbon atoms which, when reformed, tend to crack into butane and lower molecular weight hydrocarbons which are not useful as high-octane gasoline blending components. Also, the molecules with 6 carbon atoms tend to form aromatics which is undesirable because governmental environmental regulations in a number of countries limit the amount of aromatics (most particularly benzene) that gasoline may contain.[7][8][9]

It should be noted that there are a great many petroleum crude oil sources worldwide and each crude oil has its own unique composition or assay. Also, not all refineries process the same crude oils and each refinery produces its own straight-run naphthas with their own unique initial and final boiling points. In other words, naphtha is a generic term rather than a specific term.

The table just below lists some fairly typical straight-run heavy naphtha feedstocks, available for catalytic reforming, derived from various crude oils. It can be seen that they differ significantly in their content of paraffins, naphthenes and aromatics:

| Crude oil name Location |

Barrow Island Australia[10] |

Mutineer-Exeter Australia[11] |

CPC Blend Kazakhstan[12] |

Draugen North Sea[13] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial boiling point, °C | 149 | 140 | 149 | 150 |

| Final boiling point, °C | 204 | 190 | 204 | 180 |

| Paraffins, liquid volume % | 46 | 62 | 57 | 38 |

| Naphthenes, liquid volume % | 42 | 32 | 27 | 45 |

| Aromatics, liquid volume % | 12 | 6 | 16 | 17 |

Some refinery naphthas include olefinic hydrocarbons, such as naphthas derived from the fluid catalytic cracking and coking processes used in many refineries. Some refineries may also desulfurize and catalytically reform those naphthas. However, for the most part, catalytic reforming is mainly used on the straight-run heavy naphthas, such as those in the above table, derived from the distillation of crude oils.

The reaction chemistry

There are a good many chemical reactions that occur in the catalytic reforming process, all of which occur in the presence of a catalyst and a high partial pressure of hydrogen. Depending upon the type or version of catalytic reforming used as well as the desired reaction severity, the reaction conditions range from temperatures of about 495 to 525 °C and from pressures of about 5 to 45 atm.[14]

The commonly used catalytic reforming catalysts contain noble metals such as platinum and/or rhenium, which are very susceptible to poisoning by sulfur and nitrogen compounds. Therefore, the naphtha feedstock to a catalytic reformer is always pre-processed in a hydrodesulfurization unit which removes both the sulfur and the nitrogen compounds.

The four major catalytic reforming reactions are:[1]

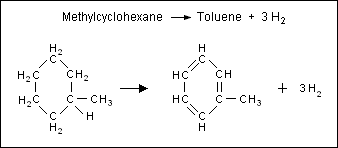

- 1: The dehydrogenation of naphthenes to convert them into aromatics as exemplified in the conversion methylcyclohexane (a naphthene) to toluene (an aromatic), as shown below:

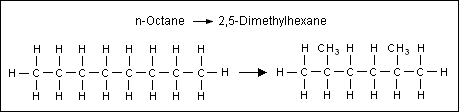

- 2: The isomerization of normal paraffins to isoparaffins as exemplified in the conversion of normal octane to 2,5-Dimethylhexane (an isoparaffin), as shown below:

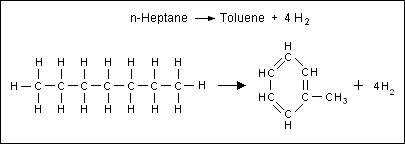

- 3: The dehydrogenation and aromatization of paraffins to aromatics (commonly called dehydrocyclization) as exemplified in the conversion of normal heptane to toluene, as shown below:

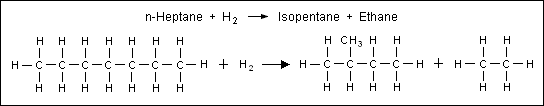

- 4: The hydrocracking of paraffins into smaller molecules as exemplified by the cracking of normal heptane into isopentane and ethane, as shown below:

The hydrocracking of paraffins is the only one of the above four major reforming reactions that consumes hydrogen. The isomerization of normal paraffins does not consume or produce hydrogen. However, both the dehydrogenation of naphthenes and the dehydrocyclization of paraffins produce hydrogen. The overall net production of hydrogen in the catalytic reforming of petroleum naphthas ranges from about 50 to 200 cubic meters of hydrogen gas (at 0 °C and 1 atm) per cubic meter of liquid naphtha feedstock. In the United States customary units, that is equivalent to 300 to 1200 standard cubic feet of hydrogen gas (at 60 °F and 1 atm) per barrel of liquid naphtha feedstock.[15] In many petroleum refineries, the net hydrogen produced in catalytic reforming supplies a significant part of the hydrogen used elsewhere in the refinery (for example, in hydrodesulfurization processes).

Process description

The most commonly used type of catalytic reforming unit has three reactors, each with a fixed bed of catalyst, and all of the catalyst is regenerated in situ during routine catalyst regeneration shutdowns which occur approximately once each 6 to 24 months. Such a unit is referred to as a semi-regenerative catalytic reformer (SRR).

Some catalytic reforming units have an extra spare or swing reactor and each reactor can be individually isolated so that any one reactor can be undergoing in-situ regeneration while the other reactors are in operation. When that reactor is regenerated, it replaces another reactor which, in turn, is isolated so that it can then be regenerated. Such units, referred to as cyclic catalytic reformers, are not very common. Cyclic catalytic reformers serve to extend the period between required shutdowns.

The latest and most modern type of catalytic reformers are called continuous catalyst regeneration reformers (CCR). Such units are characterized by continuous in-situ regeneration of part of the catalyst in a special regenerator, and by continuous addition of the regenerated catalyst to the operating reactors. As of 2006, two CCR versions are available: UOP's CCR Platformer process[16] and Axen's Octanizing process.[17] The installation and use of CCR units is rapidly increasing.

Many of the earliest catalytic reforming units (in the 1950's and 1960's) were non-regenerative in that they did not perform in-situ catalyst regeneration. Instead, when needed, the aged catalyst was replaced by fresh catalyst and the aged catalyst was shipped to catalyst manufacturers to be either regenerated or to recover the platinum content of the aged catalyst. Very few, if any, catalytic reformers currently in operation are non-regenerative.

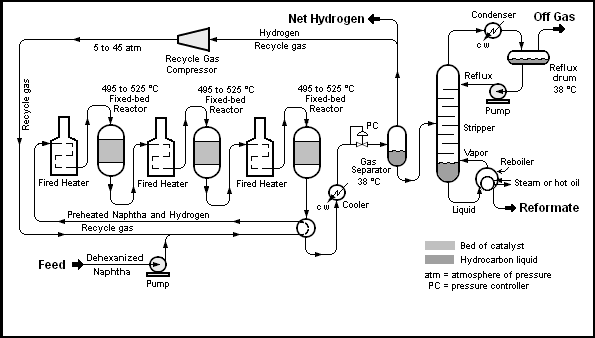

The process flow diagram below depicts a typical semi-regenerative catalytic reforming unit.

The liquid feed (at the bottom left in the diagram) is pumped up to the reaction pressure (5 to 45 atm) and is joined by a stream of hydrogen-rich recycle gas. The resulting liquid-gas mixture is preheated by flowing through a heat exchanger. The preheated feed mixture is then totally vaporized and heated to the reaction temperature (495 to 520 °C) before the vaporized reactants enter the first reactor. As the vaporized reactants flow through the fixed bed of catalyst in the reactor, the major reaction is the dehydrogenation of naphthenes to aromatics (as described earlier herein) which is highly endothermic and results in a large temperature decrease between the inlet and outlet of the reactor. To maintain the required reaction temperature and the rate of reaction, the vaporized stream is reheated in the second fired heater before it flows through the second reactor. The temperature again decreases across the second reactor and the vaporized stream must again be reheated in the third fired heater before it flows through the third reactor. As the vaporized stream proceeds through the three reactors, the reaction rates decrease and the reactors therefore become larger. At the same time, the amount of reheat required between the reactors becomes smaller. Usually, three reactors are all that is required to provide the desired performance of the catalytic reforming unit.

Some installations use three separate fired heaters as shown in the schematic diagram and some installations use a single fired heater with three separate heating coils.

The hot reaction products from the third reactor are partially cooled by flowing through the heat exchanger where the feed to the first reactor is preheated and then flow through a water-cooled heat exchanger before flowing through the pressure controller (PC) into the gas separator.

Most of the hydrogen-rich gas from the gas separator vessel returns to the suction of the recycle hydrogen gas compressor and the net production of hydrogen-rich gas from the reforming reactions is exported for use in other refinery processes that consume hydrogen (such as hydrodesulfurization units and/or a hydrocracker unit).

The liquid from the gas separator vessel is routed into a fractionating column commonly called a stabilizer. The overhead offgas product from the stabilizer contains the byproduct methane, ethane, propane and butane gases produced by the hydrocracking reactions as explained in the above discussion of the reaction chemistry of a catalytic reformer, and it may also contain some small amount of hydrogen. That offgas is routed to the refinery's central gas processing plant for removal and recovery of propane and butane. The residual gas after such processing becomes part of the refinery's fuel gas system.

The bottoms product from the stabilizer is the high-octane liquid reformate that will become a component of the refinery's product gasoline.

Catalysts and mechanisms

Most catalytic reforming catalysts contain platinum or rhenium on a silica or silica-alumina support base, and some contain both platinum and rhenium. Fresh catalyst is chlorided (chlorinated) prior to use.

The noble metals (platinum and rhenium) are considered to be catalytic sites for the dehydrogenation reactions and the chlorinated alumina provides the acid sites needed for isomerization, cyclization and hydrocracking reactions.[1]

The activity (i.e., effectiveness) of the catalyst in a semi-regenerative catalytic reformer is reduced over time during operation by carbonaceous coke deposition and chloride loss. The activity of the catalyst can be periodically regenerated or restored by in-situ high-temperature oxidation of the coke followed by chlorination. As stated earlier herein, semi-regenerative catalytic reformers are regenerated about once per 6 to 24 months.

Normally, the catalyst can be regenerated perhaps 3 or 4 times before it must be returned to the manufacturer for reclamation of the valuable platinum and/or rhenium content.[1]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Gary, J.H. and Handwerk, G.E. (1984). Petroleum Refining Technology and Economics, 2nd Edition. Marcel Dekker, Inc. ISBN 0-8247-7150-8.

- ↑ Leffler, W.L. (1985). Petroleum refining for the nontechnical person, 2nd Edition. PennWell Books. ISBN 0-87814-280-0.

- ↑ George J. Antos and Abdullah M. Aitani (Editors) (2004). Catalytic Naphtha Reforming, Second Edition. CRC Press. ISBN 0-8247-5058-6.

- ↑ James G, Speight (2006). The Chemistry and Technology of Petroleum, Fourth Edition. CRC Press. 0-8493-9067-2.

- ↑ A Biographical Memoir of Vladimir Haensel written by Stanley Gembiki, published by the National Academy of Sciences in 2006.

- ↑ Platforming described on UOP's website

- ↑ Canadian regulations on benzene in gasoline

- ↑ Briefing on Benzene in Petrol From website of United Kingdom Petroleum Industry Association (UKPIA)

- ↑ Control of Hazardous Air Pollutants from Mobile Sources: Final Rule to Reduce Mobile Source Air Toxics U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, February 2007

- ↑ Barrow Island crude oil assay

- ↑ Mutineer-Exeter crude oil assay

- ↑ CPC Blend crude oil assay

- ↑ Draugen crude oil assay

- ↑ OSHA Technical Manual, Section IV, Chapter 2, Petroleum refining Processes (A publication of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration)

- ↑ US Patent 5011805, Dehydrogenation, dehydrocyclization and reforming catalyst (Inventor: Ralph Dessau, Assignee: Mobil Oil Corporation)

- ↑ CCR Platforming (UOP website)

- ↑ Octanizing Options (Axens website)

- Pages using ISBN magic links

- Subpages

- Engineering Extra Subpages

- Chemistry Extra Subpages

- Chemical Engineering Subgroup Citable Versions

- Engineering Approved Extra Subpages

- Chemistry Approved Extra Subpages

- Citable versions of articles

- Engineering Citable Version Subpages

- Chemistry Citable Version Subpages

- All Content

- Engineering Content

- Chemistry Content

- Chemical Engineering tag