Philippines counteroffensive: Difference between revisions

Pat Palmer (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 68: | Line 68: | ||

The U.S. Eighth Army then moved on to its first landing on Mindanao (17 April), the last of the major Philippine Islands to be taken. Mindanao was followed by invasion and occupation of Panay, Cebu, Negros and several islands in the Sulu Archipelago. These islands provided bases for the U.S. Fifth and Thirteenth Air Forces to attack targets throughout the Philippines and the [[South China Sea]]. | The U.S. Eighth Army then moved on to its first landing on Mindanao (17 April), the last of the major Philippine Islands to be taken. Mindanao was followed by invasion and occupation of Panay, Cebu, Negros and several islands in the Sulu Archipelago. These islands provided bases for the U.S. Fifth and Thirteenth Air Forces to attack targets throughout the Philippines and the [[South China Sea]]. | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

{{reflist|2}} | {{reflist|2}}[[Category:Suggestion Bot Tag]] | ||

Latest revision as of 16:00, 3 October 2024

During World War Two in the Pacific, General Douglas MacArthur was deeply committed to a Philippines counteroffensive to liberate the Philippines from Japanese occupation. MacArthur had a deep emotional bond to the Philippines. MacArthur's personal ambition since leaving the Philippines in 1942 was to return.[1] He believed that the honor of the United States required the liberation of the islands and that such an objective was strategically sound. He saw Leyte as the base from which the rest of the Philippines could be taken. [2]

MacArthur and his staff responded to Marshall's suggestion on June 15, 1944, with the Reno V plan. This plan called for an October invasion of Mindanao to cover a November invasion of Leyte and further movements on a line Luzon-Bicol Peninsula-Mindonoro-Lingayen Gulf-Manila. As a bold, risky, and expensive plan, it had lots of detractors; Admiral King, and even MacArthur's air commander, General Kinney, criticized it.

Eventually, President Franklin D. Roosevelt intervened to break the deadlock between King and Nimitz versus MacArthur. Roosevelt traveled to Honolulu, accompanied by his chief of staff, Admiral Leahy, and met with MacArthur in July.[3]

Command

On the Allied side, the main battle fleet, under Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander of the Pacific and Pacific Ocean Areas. alternated between two commanders and staffs; one would carry out an operation while the other would plan the next. It was designated Third Fleet while under Vice Admiral William Halsey and Fifth Fleet while under Vice Admiral Raymond Spruance. "Type commanders", such as Marc Mitscher for Fast Carrier Forces and Willis Lee for heavy gun ships, stayed in command one level below the fleet, keeping forces ready.

This was not the key American command problem, which was more at the level of conflict between Nimitz and MacArthur. Under MacArthur was the Seventh Fleet, led by Thomas Kinkaid, principally an amphibious rather than a sea battle force. Air command was also divided, with the heaviest bombers directly under the command of Washington.

Third and Fifth Fleet staff agreed on three naval objectives in support of land operations:[4]

- Air strikes by Third Fleet and long-range land-based aircraft on Okinawa, Formosa, and Northern Leyte on October 10-13.

- Attacks by the Seventh Fleet on Bicol Peninsula, Leyte, Cebu and Negros, and direct supports of the actual landings, October 16-20.

- "Strategic support" (which wasn't clearly defined) by the Third Fleet from October 21 onwards.

Both Halsey and Spruance were strong commanders with very different styles. Halsey himself speculated that the outcome, for the Allies, might have been better if he, rather than Spruance, had commanded at the Philippine Sea, while Spruance had taken his place at Leyte Gulf. War is filled with might-have-beens.

Preparatory operations

On 9-10 September, Third Fleet units, supporting impending landings on Morotai and Palau, made air strikes on Mindonoro, and discovered significant weaknesses in Japanese air defense. It was determined that Southwest Pacific land-based bombers, operating out of New Guinea fields, had caused severe damage to enemy air installations on the island. Exploiting the weakness, the Third Fleet raided the Visayas on 12-13 September, causing substantial damage to aircraft and airfields. [5]

MacArthur chose to occupy Morotai Island, off Halmahera, as an intermediate base, with landings starting on 15 September by the U.S. Army 31st Division and 126th Regimental Combat Team of the 32nd Division plus supporting combat and service troops, directed by XI Corps. Simultaneously, the 1st Division, U.S. Marine Corps, followed by the Army's 81st Division, took Palau and Angaur in the Palau group. Ulithi was taken on the 23rd.[6]

Morotai and Palau, 350-500 miles from Leyte, became the main bases for Army fighters, still distant for WWII aircraft. Ulithi became the main staging harbor. Two-pronged drives to capture Japanese-held islands, building a ever-closer set of airfields for attacks on the Japanese home islands. In two key cases, an initial American landing was followed by a sea battle against supporting and reinforcing forces. While the Allies won the sea battles, both were troubled by problems of divided command.

Initial landings

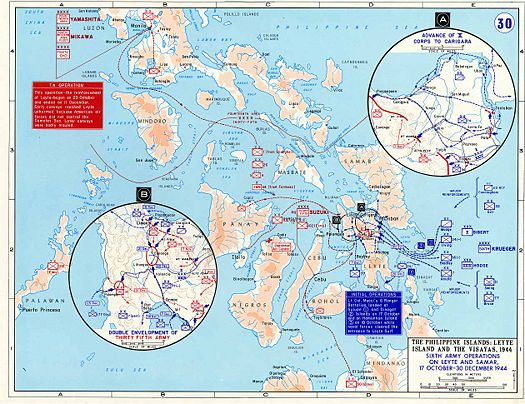

On 20 October 1944, the Sixth United States Army, under Gen. Walter Krueger, supported by naval and air bombardment, landed on the favorable eastern shore of Leyte, one of the three large Philippine Islands, north of Mindanao. United States Seventh Fleet, under Thomas Kinkaid, conducted the amphibious operations and remained in support.

Leyte Gulf 1944

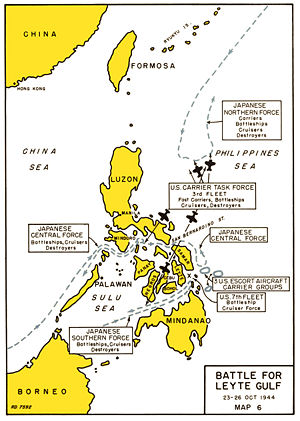

The Battle of Leyte Gulf, October 23-26, 1944, was the largest naval battle in history. It involved coordinated Japanese attacks designed to hit the hundreds of thousands of American soldiers who had just landed at Leyte Gulf, and their supply ships. Severe communications failures on both sides characterized the battle, which ended in a total American victory and the end of Japanese sea power.

Japan was heavily outgunned, so it designed a trick that would neutralize American strength. Sho-1 called for using the remaining Japanese carriers as a decoy, knowing they would all be destroyed, to pull the main American battle fleet, the Third Fleet, north away from the real action. Then two other Japanese fleets would attack Leyte from the center and the south.[7] The plan almost worked, but the Japanese had poor radios and the different units were not in touch; the Japanese Army knew what was happening but it never talked to the Navy and did not help out.

Land invasion expands

The U.S. Sixth Army continued its advance from the east, as the Japanese rushed reinforcements to the Ormoc Bay area on the western side of the island. While the Sixth Army was reinforced successfully, the U.S. Fifth Air Force was able to devastate the Japanese attempts to resupply. In torrential rains and over difficult terrain, the advance continued across Leyte and the neighboring island of Samar to the north. On 7 December 1944, U.S. Army units landed at Ormoc Bay and, after a major land and air battle, cut off the Japanese ability to reinforce and supply Leyte. Although fierce fighting continued on Leyte for months, the U.S. Army was in control.

On 15 December 1944, landings against minimal resistance were made on the southern beaches of the island of Mindoro, a key location in the planned Lingayen Gulf operations, in support of major landings scheduled on Luzon. On 9 January 1945, on the south shore of Lingayen Gulf on the western coast of Luzon, General Krueger's Sixth Army landed his first units. Almost 175,000 men followed across the twenty-mile beachhead within a few days. With heavy air support, Army units pushed inland, taking Clark Field, 40 miles northwest of Manila, in the last week of January.

Two more major landings followed, one to cut off the Bataan Peninsula, and another, that included a parachute drop, south of Manila. Pincers closed on the city and, on 3 February 1945, elements of the 1st Cavalry Division pushed into the northern outskirts of Manila and the 8th Cavalry passed through the northern suburbs and into the city itself.

As the advance on Manila continued from the north and the south, the Bataan Peninsula was rapidly secured. On 16 February, paratroopers and amphibious units assaulted Corregidor, and resistance ended there on 27 February.

In all, ten U.S. divisions and five independent regiments battled on Luzon, making it the largest campaign of the Pacific war, involving more troops than the United States had used in North Africa, Italy, or southern France.

Palawan Island, between Borneo and Mindoro, the fifth largest and western-most Philippine Island, was invaded on 28 February, with landings of the Eighth Army at Puerto Princesa. The Japanese put up little direct defense of Palawan, but cleaning up pockets of Japanese resistance lasted until late April, as the Japanese used their common tactic of withdrawing into the mountain jungles, disbursed as small units. Throughout the Philippines, U.S. forces were aided by Filipino guerrillas to find and dispatch the holdouts.

The U.S. Eighth Army then moved on to its first landing on Mindanao (17 April), the last of the major Philippine Islands to be taken. Mindanao was followed by invasion and occupation of Panay, Cebu, Negros and several islands in the Sulu Archipelago. These islands provided bases for the U.S. Fifth and Thirteenth Air Forces to attack targets throughout the Philippines and the South China Sea.

References

- ↑ "The Philippine Islands constituted the main objective of General MacArthur's planning from the time of his departure from Corregidor in March 1942 until his dramatic return to Leyte two and one half years later," , CHAPTER VII--THE PHILIPPINES: STRATEGIC OBJECTIVE, Reports of General MacArthur, Office of the Chief of Military History, U.S. Army, 1966

- ↑ , Chapter VIII, The Leyte Operation, Reports of General MacArthur: The Campaigns of MacArthur in the Pacific, Office of the Chief of Military History, U.S. Army, 1966

- ↑ Samuel Eliot Morison (1970), History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, vol. Volume XII: Leyte, June 1944-January 1945, Atlantic Monthly/Little, Brown, pp. 8-11

- ↑ Morison, 57.

- ↑ Macarthur Reports, Chapter 7, pp. 172-173

- ↑ Macarthur Reports, Chapter 7, pp. 175-178

- ↑ For the relative strengths of the fleets see Vincent P. O'Hara, The U.S. Navy Against the Axis: Surface Combat, 1941-1945 (2007) pp 261-2