California, history since 1846: Difference between revisions

imported>Richard Jensen (import from Wiki) |

imported>Richard Jensen (cleanup) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{ | This article continues the '''history of California''' since the American conquest of 1846. | ||

For earlier history see [[California, History to 1845]].'' | |||

==American era== | |||

===Bear Flag Revolt and American conquest=== | |||

{{main|Mexican-American War}} | |||

When war was declared in May 13, 1846 between the United States and Mexico, it took almost two months (mid-July 1846) for definite word of war to get to California. U.S. consul [[Thomas O. Larkin]], stationed in Monterey, on hearing rumors of war tried to keep peace between the Americans and the small Mexican military garrison commanded by José Castro. American army captain [[John C. Frémont]] with about 60 well-armed men had entered California in December 1845 and was making a slow march to Oregon when they received word that war between Mexico and the U.S. was imminent.<ref> See [http://www.militarymuseum.org/fremont.html]</ref> | |||

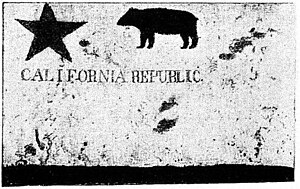

[[Image:firstbearflag.jpg|left|thumb|300px|A replica of the first "Bear Flag" now at [[Presidio of Sonoma|El Presidio de Sonoma]], or ''Sonoma Barracks''.]] | |||

On June 15, 1846, some 30 settlers, mostly Americans, staged a revolt and seized the small Mexican garrison in [[Sonoma, California|Sonoma]]. They made up a flag and raised the "[[Bear Flag]]" over Sonoma. Days later the U.S. Army, led by Fremont, took over on June 23. The California state flag today is based on this original Bear Flag, and continues to contain the words "California Republic." | |||

Commodore [[John Drake Sloat]], on hearing of imminent war and the revolt in Sonoma, ordered his naval forces to occupy ''Yerba Buena'' (present [[San Francisco]]) on July 7 and raise the American flag. On July 15, Sloat transferred his command to Commodore [[Robert F. Stockton]], a much more aggressive leader. Commodore Stockton put Frémont's forces under his orders. On July 19th, Frémont's "California Battalion" swelled to about 160 additional men from newly arrived settlers near Sacramento, and he entered [[Monterey, California|Monterey]] in a joint operation with some of Stockton's sailors and marines. The official word had been received -- the [[Mexican-American War]] was on. The American forces easily took over the north of California; within days they controlled San Francisco, Sonoma, and Sutter's Fort in Sacramento. | |||

In Southern California, Mexican General [[José Castro]] and Governor [[Pío Pico]] fled from Los Angeles. When Stockton's forces entered [[Los Angeles]] unresisted on August 13, 1846, the nearly bloodless conquest of California seemed complete. Stockton, however, left too small a force (36 men) in Los Angeles, and the [[Californios]], acting on their own and without help from Mexico, led by [[José Mariá Flores]] , forced the small American garrison to retire in late September. 200 Reinforcements sent by Stockton, led by US Navy Capt [[William Mervine]] were repulsed in the [[Battle of Dominguez Rancho]] [[October 7]] through [[October 9]], [[1846]], near [[San Pedro]], where 14 [[US Marines]] were killed. Meanwhile, General Kearny with a much reduced squadron of 100 dragoons finally reached California after a grueling march across New Mexico, Arizona and the Sonora desert. On December 6, 1846, They fought the [[Battle of San Pasqual]] near San Diego, California, where 18 of Kearny's troop were killed--the largest American casualties lost in battle in California. | |||

Stockton rescued Kearny's surrounded forces and with their combined force, they moved northward from San Diego, entering the Los Angeles area on [[January 8]], [[1847]], linking up with Frémont's men and with American forces totaling 660 troops, they fought the Californios in the [[Battle of Rio San Gabriel]] and the next day, on [[January 9]], [[1847]], they fought the [[Battle of La Mesa]]. Three days later, on [[January 12]], [[1847]], the last significant body of Californios surrendered to American forces. That marked the end of the War in California. On [[January 13]], [[1847]], the [[Treaty of Cahuenga]] was signed. | |||

On [[January 28]], [[1847]], Army lieutenant William Tecumseh Sherman and his army unit arrived in Monterey, California as American forces in the pipeline continued to stream into California. On [[March 15]], [[1847]], Col. Jonathan D. Stevenson’s Seventh Regiment of New York Volunteers of about 900 men start arriving in California. All of these men were in place when gold was discovered in January 1848. | |||

The [[Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo]], signed on [[February 2]] [[1848]], marked the end of the Mexican-American War. In that treaty, the United States agreed to pay Mexico $18,250,000; Mexico formally ceded California (and other northern territories) to the United States, and a new international boundary was drawn; San Diego Bay is one of the only natural harbors in California south of San Francisco, and to claim all this strategic water, the border was slanted to include it. | |||

===Gold Rush=== | |||

{{main|California Gold Rush}} | |||

In January 1848, [[gold]] was discovered at [[Sutter's Mill]] in the [[Sierra Nevada (US)|Sierra Nevada]] foothills about 40 miles east of [[Sacramento, California|Sacramento]] — beginning the [[California Gold Rush]], which had the most extensive impact on population growth of the state of any era [http://www.learncalifornia.org/doc.asp?id=1934] [http://americanhistory.about.com/library/weekly/aa090901a.htm]. | |||

The miners and merchants settled in towns along what is now State Highway 49, and settlements sprang up along the [[Siskiyou Trail]] as gold was discovered elsewhere in California (notably in [[Siskiyou County]]). The nearest deep-water seaport was [[San Francisco Bay]], and San Francisco became the home for bankers who financed exploration for gold. | |||

The Gold Rush brought the world to California. By 1855, some 300,000 "[[California Gold Rush#Forty-Niners|Forty-Niners]]" had arrived from every continent; many soon left, of course--some rich, most not very rich. A precipitous drop in the Native American population occurred in the decade after the discovery of gold. | |||

===Statehood: 1849-1850=== | |||

In 1847-49 California was run by the U.S. military; local government continued to be run by alcaldes (mayors) in most places; but now some were Americans. Bennett Riley, the last military governor, called a constitutional convention to meet in Monterey in September 1849. Its 48 delegates were mostly pre-1846 American settlers; 8 were Californios. They unanimously outlawed slavery and set up a state government that operated for 10 months before California was given official statehood by Congress on [[September 9]], [[1850]] as part of the [[Compromise of 1850]]. <ref>Richard B. Rice et al, ''The Elusive Eden'' (1988) 191-95</ref> A series of small towns were used briefly as the state capital until finally Sacramento was selected in 1854. | |||

===The Civil War=== | |||

{{main|California and the Civil War}} | |||

Because of the distance factor, California played a minor role in the [[American Civil War]]. Although some settlers sympathized with the Confederacy, they were not allowed to organize and their newspapers were closed down. Former Senator [[William Gwin]], a Confederate sympathizer, was arrested and fled to Europe. Powerful capitalists dominated in Californian politics through their control of mines, shipping, and finance controlled the state through the new Republican party. Nearly all the men who volunteered as soldiers stayed in the West to guard facilities. Some 2,350 men in the [[California Column]] marched east across Arizona in 1862 to expel the Confederates from Arizona and New Mexico. The California Column spent most of its energy fighting hostile Indians. | |||

===Labor politics and the rise of Nativism=== | |||

After the Civil War ended in 1865, California continued to grow rapidly. Independent miners were largely displaced by large corporate mining operations. Railroads began to be built, and both the railroad companies and the mining companies began to hire large numbers of laborers. The decisive event was the opening of the transcontinental railroad in 1869; six days by train brought a traveller from Chicago to San Francisco, compared to six months by ship. Thousands of Chinese men arrived, lured by high cash wages. They were expelled from the mine fields. Most returned to China after the Central Pacific was built. Those who stayed mostly moved to the Chinatown in San Francisco and a few other cities, where they were relatively safe from violent attacks they suffered elsewhere. | |||

From 1850 through 1900, anti-Chinese [[nativist]] sentiment resulted in the passage of innumerable laws, many of which remained in effect well into the middle of the 20th century. The most flagrant episode was probably the creation and ratification of a new state constitution in 1879. Thanks to vigorous lobbying by the anti-Chinese Workingmen's Party, led by [[Dennis Kearney]] (an immigrant from Ireland), Article XIX, section 4 forbade corporations from hiring Chinese coolies, and empowered all California cities and counties to completely expel Chinese persons or to limit where they could reside. It was repealed in 1952. | |||

The 1879 constitutional convention also dispatched a message to Congress pleading for strong immigration restrictions, which led to the passage of the [[Chinese Exclusion Act (United States)|Chinese Exclusion Act]] in 1882. The Act was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1889, and it would not be repealed by Congress until 1943. Similar sentiments led to the development of a [[Gentlemen's Agreement]] with [[Japan]], by which Japan voluntarily agreed to restrict emigration to the United States. California also passed an Alien Land Act which barred aliens, especially [[Asian]]s, from holding title to land. Because it was difficult for people born in Asia to obtain U.S. citizenship until the 1960s, land ownership titles were held by their American-born children, who were full citizens. The law was overturned by the [[California Supreme Court]] as unconstitutional in 1952. | |||

In 1886, when a Chinese [[laundry]] owner challenged the constitutionality of a San Francisco ordinance clearly designed to drive Chinese laundries out of business, the [[U.S. Supreme Court]] ruled in his favor, and in doing so, laid the theoretical foundation for modern equal protection constitutional law. See ''[[Yick Wo v. Hopkins]]'', 118 U.S. 356 (1886). Meanwhile, even with severe restrictions on Asian immigration, tensions between unskilled workers and wealthy landowners persisted up to and through the Great Depression. [[Novelist]] [[Jack London]] writes of the struggles of workers in the city of [[Oakland, California|Oakland]] in his visionary classic, ''Valley of the Moon'', a title evoking the pristine situation of [[Sonoma County, California|Sonoma County]] between sea and mountains, [[Sequoia|Redwoods]] and [[Oak]]s, fog and sunshine. | |||

===Rise of the railroads=== | |||

{{main|California and the railroads}} | |||

The establishment of America's [[Transcontinental railroad#United States|transcontinental rail lines]] permanently linked [[California]] to the rest of the country, and the far-reaching transportation systems that grew out of them during the century that followed contributed immeasurably to the state’s unrivaled social, political, and economic development. | |||

===Feats of engineering=== | ===Feats of engineering=== | ||

Beginning at the turn of the [[twentieth century]], there were several daring feats of engineering in Californian history. First is the [[Los Angeles Aqueduct]], which runs from the [[Owens Valley]], through the [[Mojave Desert]] and its [[Antelope Valley]], to dry Los Angeles far to the south. Finished in 1911, it was the brain-child of the self-taught [[William Mulholland]] and is still in use today. Creeks flowing from the eastern Sierra are diverted into the aqueduct. This attracts controversy from time to time since this withholds water from [[Mono Lake]] — an especially otherworldly and beautiful ecosystem — and from farmers in the [[Owens Valley]]. ''See also'' [[California Water Wars]]. | Beginning at the turn of the [[twentieth century]], there were several daring feats of engineering in Californian history. First is the [[Los Angeles Aqueduct]], which runs from the [[Owens Valley]], through the [[Mojave Desert]] and its [[Antelope Valley]], to dry Los Angeles far to the south. Finished in 1911, it was the brain-child of the self-taught [[William Mulholland]] and is still in use today. Creeks flowing from the eastern Sierra are diverted into the aqueduct. This attracts controversy from time to time since this withholds water from [[Mono Lake]] — an especially otherworldly and beautiful ecosystem — and from farmers in the [[Owens Valley]]. ''See also'' [[California Water Wars]]. | ||

| Line 80: | Line 124: | ||

Schwarzenegger began his shortened term with a soaring approval rating and soon after began implementing a conservative agenda. This initially resulted in sparring with the heavily Democratic Assembly and Senate over the state budget, battles which provided his infamous "girly men" comment but also began taking their toll on his approval rating. Schwarzenegger then embarked on a campaign to enact several ballot propositions in a 2005 Special Election touted as reforming California's budget system, redistricting powers, and union political fundraising. The union-led campaign spearheaded by the California Nurses Association contributed heavily to the defeat of every proposition in the Special Election. Since this conspicuous failure, Schwarzenegger has made a turn back to the left, criticizing the Bush Administration at many junctures, reviving his environmental agenda, and compromising with the legislature on the traditionally Democratic issue of education spending. His approval rating has also been revived, and was re-elected. | Schwarzenegger began his shortened term with a soaring approval rating and soon after began implementing a conservative agenda. This initially resulted in sparring with the heavily Democratic Assembly and Senate over the state budget, battles which provided his infamous "girly men" comment but also began taking their toll on his approval rating. Schwarzenegger then embarked on a campaign to enact several ballot propositions in a 2005 Special Election touted as reforming California's budget system, redistricting powers, and union political fundraising. The union-led campaign spearheaded by the California Nurses Association contributed heavily to the defeat of every proposition in the Special Election. Since this conspicuous failure, Schwarzenegger has made a turn back to the left, criticizing the Bush Administration at many junctures, reviving his environmental agenda, and compromising with the legislature on the traditionally Democratic issue of education spending. His approval rating has also been revived, and was re-elected. | ||

== | ==Bibliography== | ||

===Surveys=== | |||

=== | |||

* Bakken, Gordon Morris. ''California History: A Topical Approach'' (2003) | * Bakken, Gordon Morris. ''California History: A Topical Approach'' (2003) | ||

* Robert W. Cherny, Richard Griswold del Castillo, and Gretchen Lemke-Santangelo. ''Competing Visions: A History Of California'' (2005) | * Robert W. Cherny, Richard Griswold del Castillo, and Gretchen Lemke-Santangelo. ''Competing Visions: A History Of California'' (2005) | ||

| Line 106: | Line 146: | ||

** ''Coast of Dreams: California on the Edge, 1990-2003'' (2004) | ** ''Coast of Dreams: California on the Edge, 1990-2003'' (2004) | ||

* Sucheng, Chan , and Spencer C. Olin, eds. ''Major Problems in California History'' (1996) | * Sucheng, Chan , and Spencer C. Olin, eds. ''Major Problems in California History'' (1996) | ||

====1846-1900==== | |||

* Brands, H.W. ''The Age of Gold: The California Gold Rush and the New American Dream'' (2003) | |||

* Burchell, Robert A. "The Loss of a Reputation; or, The Image of California in Britain before 1875," ''California Historical Quarterly'' 53 (Summer I974): 115-30, stories about Gold Rush lawlessness slowed immigration for two decades | |||

* Burns, John F. and Richard J. Orsi, eds; ''Taming the Elephant: Politics, Government, and Law in Pioneer California'' U. of California Press, (2003) [[http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=105960680 online edition] | |||

* Jelinek, Lawrence. ''Harvest Empire: A History of California Agriculture'' (1982) | |||

* McAfee, Ward. ''California's Railroad Era, 1850-1911'' (1973) | |||

* Olin, Spencer. ''California Politics, 1846-1920'' (1981) | |||

* Pitt, Leonard. ''The Decline of the Californios: A Social History of the Spanish-Speaking Californians, 1846-1890'' (1966) (ISBN 0-520-01637-8) | |||

* Saxton, Alexander. ''The Indispensable Enemy: Labor and the Anti-Chinese Movement in California'' (1971) (ISBN 0-520-02905-4) | |||

* Starr, Kevin. ''Americans and the California Dream, 1850-1915'' (1986) | |||

* Starr, Kevin and Richard J. Orsi eds. ''Rooted in Barbarous Soil: People, Culture, and Community in Gold Rush California'' (2001), articles by scholars | |||

* Tutorow , Norman E. ''Leland Stanford Man of Many Careers''(1971) | |||

* Williams, R. Hal. ''The Democratic Party and California Politics, 1880-1896'' (1973) | |||

* [http://www.1849.org/index2.html Gold, Greed & Genocide] | |||

* [http://www.bearflagmuseum.org/ The Bear Flag Museum] | |||

* [http://www.bearflagmuseum.org/BancroftIntroTOC.html Bancroft History of California Vol V. Bear Flag Revolt] | |||

=== | ===1900-2007=== | ||

* [http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=100946216 Abelmann, Nancy, and John Lie. ''Blue Dreams: Korean Americans and the Los Angeles Riots'' (1995)] | * [http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=100946216 Abelmann, Nancy, and John Lie. ''Blue Dreams: Korean Americans and the Los Angeles Riots'' (1995)] | ||

* Fogelson, Robert M. ''The Fragmented Metropolis: Los Angeles, 1850-1930'' (1993) | * Fogelson, Robert M. ''The Fragmented Metropolis: Los Angeles, 1850-1930'' (1993) | ||

| Line 117: | Line 174: | ||

* Sitton, Tom and William F, Deverell, eds. ''Metropolis in the Making: Los Angeles in the 1920s'' (2001) | * Sitton, Tom and William F, Deverell, eds. ''Metropolis in the Making: Los Angeles in the 1920s'' (2001) | ||

* Danielle Jean Swiontek. ''With Ballots and Pocketbooks: Women, Labor, and Reform in Progressive California'' (2006) | * Danielle Jean Swiontek. ''With Ballots and Pocketbooks: Women, Labor, and Reform in Progressive California'' (2006) | ||

Revision as of 04:09, 26 April 2007

This article continues the history of California since the American conquest of 1846. For earlier history see California, History to 1845.

American era

Bear Flag Revolt and American conquest

When war was declared in May 13, 1846 between the United States and Mexico, it took almost two months (mid-July 1846) for definite word of war to get to California. U.S. consul Thomas O. Larkin, stationed in Monterey, on hearing rumors of war tried to keep peace between the Americans and the small Mexican military garrison commanded by José Castro. American army captain John C. Frémont with about 60 well-armed men had entered California in December 1845 and was making a slow march to Oregon when they received word that war between Mexico and the U.S. was imminent.[1]

On June 15, 1846, some 30 settlers, mostly Americans, staged a revolt and seized the small Mexican garrison in Sonoma. They made up a flag and raised the "Bear Flag" over Sonoma. Days later the U.S. Army, led by Fremont, took over on June 23. The California state flag today is based on this original Bear Flag, and continues to contain the words "California Republic."

Commodore John Drake Sloat, on hearing of imminent war and the revolt in Sonoma, ordered his naval forces to occupy Yerba Buena (present San Francisco) on July 7 and raise the American flag. On July 15, Sloat transferred his command to Commodore Robert F. Stockton, a much more aggressive leader. Commodore Stockton put Frémont's forces under his orders. On July 19th, Frémont's "California Battalion" swelled to about 160 additional men from newly arrived settlers near Sacramento, and he entered Monterey in a joint operation with some of Stockton's sailors and marines. The official word had been received -- the Mexican-American War was on. The American forces easily took over the north of California; within days they controlled San Francisco, Sonoma, and Sutter's Fort in Sacramento.

In Southern California, Mexican General José Castro and Governor Pío Pico fled from Los Angeles. When Stockton's forces entered Los Angeles unresisted on August 13, 1846, the nearly bloodless conquest of California seemed complete. Stockton, however, left too small a force (36 men) in Los Angeles, and the Californios, acting on their own and without help from Mexico, led by José Mariá Flores , forced the small American garrison to retire in late September. 200 Reinforcements sent by Stockton, led by US Navy Capt William Mervine were repulsed in the Battle of Dominguez Rancho October 7 through October 9, 1846, near San Pedro, where 14 US Marines were killed. Meanwhile, General Kearny with a much reduced squadron of 100 dragoons finally reached California after a grueling march across New Mexico, Arizona and the Sonora desert. On December 6, 1846, They fought the Battle of San Pasqual near San Diego, California, where 18 of Kearny's troop were killed--the largest American casualties lost in battle in California.

Stockton rescued Kearny's surrounded forces and with their combined force, they moved northward from San Diego, entering the Los Angeles area on January 8, 1847, linking up with Frémont's men and with American forces totaling 660 troops, they fought the Californios in the Battle of Rio San Gabriel and the next day, on January 9, 1847, they fought the Battle of La Mesa. Three days later, on January 12, 1847, the last significant body of Californios surrendered to American forces. That marked the end of the War in California. On January 13, 1847, the Treaty of Cahuenga was signed.

On January 28, 1847, Army lieutenant William Tecumseh Sherman and his army unit arrived in Monterey, California as American forces in the pipeline continued to stream into California. On March 15, 1847, Col. Jonathan D. Stevenson’s Seventh Regiment of New York Volunteers of about 900 men start arriving in California. All of these men were in place when gold was discovered in January 1848.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed on February 2 1848, marked the end of the Mexican-American War. In that treaty, the United States agreed to pay Mexico $18,250,000; Mexico formally ceded California (and other northern territories) to the United States, and a new international boundary was drawn; San Diego Bay is one of the only natural harbors in California south of San Francisco, and to claim all this strategic water, the border was slanted to include it.

Gold Rush

In January 1848, gold was discovered at Sutter's Mill in the Sierra Nevada foothills about 40 miles east of Sacramento — beginning the California Gold Rush, which had the most extensive impact on population growth of the state of any era [1] [2].

The miners and merchants settled in towns along what is now State Highway 49, and settlements sprang up along the Siskiyou Trail as gold was discovered elsewhere in California (notably in Siskiyou County). The nearest deep-water seaport was San Francisco Bay, and San Francisco became the home for bankers who financed exploration for gold.

The Gold Rush brought the world to California. By 1855, some 300,000 "Forty-Niners" had arrived from every continent; many soon left, of course--some rich, most not very rich. A precipitous drop in the Native American population occurred in the decade after the discovery of gold.

Statehood: 1849-1850

In 1847-49 California was run by the U.S. military; local government continued to be run by alcaldes (mayors) in most places; but now some were Americans. Bennett Riley, the last military governor, called a constitutional convention to meet in Monterey in September 1849. Its 48 delegates were mostly pre-1846 American settlers; 8 were Californios. They unanimously outlawed slavery and set up a state government that operated for 10 months before California was given official statehood by Congress on September 9, 1850 as part of the Compromise of 1850. [2] A series of small towns were used briefly as the state capital until finally Sacramento was selected in 1854.

The Civil War

Because of the distance factor, California played a minor role in the American Civil War. Although some settlers sympathized with the Confederacy, they were not allowed to organize and their newspapers were closed down. Former Senator William Gwin, a Confederate sympathizer, was arrested and fled to Europe. Powerful capitalists dominated in Californian politics through their control of mines, shipping, and finance controlled the state through the new Republican party. Nearly all the men who volunteered as soldiers stayed in the West to guard facilities. Some 2,350 men in the California Column marched east across Arizona in 1862 to expel the Confederates from Arizona and New Mexico. The California Column spent most of its energy fighting hostile Indians.

Labor politics and the rise of Nativism

After the Civil War ended in 1865, California continued to grow rapidly. Independent miners were largely displaced by large corporate mining operations. Railroads began to be built, and both the railroad companies and the mining companies began to hire large numbers of laborers. The decisive event was the opening of the transcontinental railroad in 1869; six days by train brought a traveller from Chicago to San Francisco, compared to six months by ship. Thousands of Chinese men arrived, lured by high cash wages. They were expelled from the mine fields. Most returned to China after the Central Pacific was built. Those who stayed mostly moved to the Chinatown in San Francisco and a few other cities, where they were relatively safe from violent attacks they suffered elsewhere.

From 1850 through 1900, anti-Chinese nativist sentiment resulted in the passage of innumerable laws, many of which remained in effect well into the middle of the 20th century. The most flagrant episode was probably the creation and ratification of a new state constitution in 1879. Thanks to vigorous lobbying by the anti-Chinese Workingmen's Party, led by Dennis Kearney (an immigrant from Ireland), Article XIX, section 4 forbade corporations from hiring Chinese coolies, and empowered all California cities and counties to completely expel Chinese persons or to limit where they could reside. It was repealed in 1952.

The 1879 constitutional convention also dispatched a message to Congress pleading for strong immigration restrictions, which led to the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882. The Act was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1889, and it would not be repealed by Congress until 1943. Similar sentiments led to the development of a Gentlemen's Agreement with Japan, by which Japan voluntarily agreed to restrict emigration to the United States. California also passed an Alien Land Act which barred aliens, especially Asians, from holding title to land. Because it was difficult for people born in Asia to obtain U.S. citizenship until the 1960s, land ownership titles were held by their American-born children, who were full citizens. The law was overturned by the California Supreme Court as unconstitutional in 1952.

In 1886, when a Chinese laundry owner challenged the constitutionality of a San Francisco ordinance clearly designed to drive Chinese laundries out of business, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in his favor, and in doing so, laid the theoretical foundation for modern equal protection constitutional law. See Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886). Meanwhile, even with severe restrictions on Asian immigration, tensions between unskilled workers and wealthy landowners persisted up to and through the Great Depression. Novelist Jack London writes of the struggles of workers in the city of Oakland in his visionary classic, Valley of the Moon, a title evoking the pristine situation of Sonoma County between sea and mountains, Redwoods and Oaks, fog and sunshine.

Rise of the railroads

The establishment of America's transcontinental rail lines permanently linked California to the rest of the country, and the far-reaching transportation systems that grew out of them during the century that followed contributed immeasurably to the state’s unrivaled social, political, and economic development.

Feats of engineering

Beginning at the turn of the twentieth century, there were several daring feats of engineering in Californian history. First is the Los Angeles Aqueduct, which runs from the Owens Valley, through the Mojave Desert and its Antelope Valley, to dry Los Angeles far to the south. Finished in 1911, it was the brain-child of the self-taught William Mulholland and is still in use today. Creeks flowing from the eastern Sierra are diverted into the aqueduct. This attracts controversy from time to time since this withholds water from Mono Lake — an especially otherworldly and beautiful ecosystem — and from farmers in the Owens Valley. See also California Water Wars.

Other feats are the building of Hoover Dam (which is in Nevada, but provides power and water to Southern California), Hetch Hetchy Reservoir, Shasta Dam, and the California Aqueduct, taking water from northern California to dry and sprawling southern California. Another project was the draining of Lake Tulare, which, during high water was the largest fresh-water lake inside an American state. This created a large wet area amid the dry San Joaquin Valley and swamps abounded at its shores. By the 1970s, it was completely drained, but it attempts to resurrect itself during heavy rains.

Automobile travel became important after 1910. A key route was the Lincoln Highway, which was America's first transcontinental road for motorized vehicles, connecting New York City to San Francisco. The creation of the Lincoln Highway in 1913 was a major stimulus on the development of both industry and tourism in the state. Similar effects occurred in 1926 with the creation of Route 66.

Oil, movies, and the military

In the 1920s, oil was discovered, first near Newhall, in northern Los Angeles County. Soon, more oil was found all over the L.A. Basin and other parts of California. It soon became the most profitable industry in the southern part of the state.

The first decades of the twentieth century saw the rise of the studio system. MGM, Universal and Warner Brothers all acquired land in Hollywood, which was then a small subdivision known as "Hollywoodland" on the outskirts of Los Angeles.

Soon, Americans from all over the country, especially the Midwest, were attracted to the mild Mediterranean climate, cheap land, and a wide variety of geography within a short drive by truck. Many westerns of this era were shot in the Owens Valley, east of the Sierra Nevada mountain range, wherein rises Mount Whitney, the tallest mountain in the contiguous United States. Desert movies were shot in the Mojave or in Death Valley, the lowest point and hottest place in the western hemisphere. Pirate movies were shot in Carmel. Winter movies were shot in the San Bernardino Mountains. Movies set in the Mediterranean or the eastern U.S. were shot on location, or in outdoor sets on studio land, with simulated rain or snow as needed.

By the 1930s the show-biz population had extended its reach into radio, and by mid-century Southern California had also become a major center of television production, hosting studios for major networks such as NBC and CBS. In the 1934 Governor's election, novelist Upton Sinclair was the narrowly defeated Democratic nominee, running on the programme of the socialist EPIC Movement, a radical response to the Great Depression.

During World War II, California's mild climate became a major resource for the war effort. Numerous air-training bases were established in Southern California, where most aircraft manufacturers, including Douglas Aircraft and Hughes Aircraft expanded or established factories. Major naval, shipyards were established or expanded in San Diego, Long Beach and San Francisco Bay. San Francisco was the home of the liberty ships.

Baby boomers and free spirits

After the war, hundreds of land developers bought land cheap, subdivided it, built on it, and got rich. Real-estate development replaced oil and agriculture as Southern California's principal industry. In 1955, Disneyland opened in Anaheim. In 1958, Major League Baseball's Dodgers and Giants left New York City and came to Los Angeles and San Francisco, respectively. The population of California expanded dramatically, to nearly 20 million by 1970. This was the coming-of-age of the baby boom.

In the late 1960s the baby-boom generation reached draft age, and many risked arrest to oppose the war in Vietnam. There were numerous demonstrations and strikes, most famously on the prestigious Berkeley campus of the University of California, across the bay from San Francisco. In 1965, race riots erupted in Watts, in the South-Central area of Los Angeles. The hippie riots on the Sunset Strip in Los Angeles were also immortalized by the Buffalo Springfield in "For What It's Worth." (1966). Some commentators predicted revolution. Then the federal government promised to withdraw from the Vietnam War, which at last happened in 1974. The radical political movements, having achieved a large part of their aim, lost members and funding.

California still was a land of free spirits, open hearts, easy-going living. Popular music of the period bore titles such as "California Girls", "California Dreamin'", "San Francisco", "Do You Know the Way to San Jose?" and "Hotel California". These reflected the Californian promise of easy living in a paradisiacal climate. The surfing culture burgeoned. Many took low-paying jobs and joined the surfers living in trailers at the beach and many others forsook ambition and joined the hippies free living in cities.

The most famous hippie hangout was the Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco. The state's cities, especially San Francisco, became famous for their gentility and tolerance. A distinctive and idyllic Californian culture emerged for a time. The peak of this culture, in 1967, was known as the Summer of Love. California became known elsewhere in the U.S. often derogatorily, and with envy as the "land of fruits and nuts," but Californians themselves knew this as a pleasant life.

Economic power house

Conversely, during the same period, the Golden State also attracted commercial and industrial expansion of astronomical rates. The adoption of a Master Plan for Higher Education in 1960 allowed the development of a highly efficient system of public education in the Community Colleges and the University of California and California State University systems; by creating an educated workforce, it attracted investment, particularly in areas related to high technology. By 1980, California became recognized as the world's eighth-largest economy. Millions of workers were needed to fuel the expansion. The high population of the time caused tremendous problems with urban sprawl, traffic, pollution, and, to a lesser extent, crime.

Urban sprawl created a backlash in many urban areas, with the local governments limiting growth beyond certain boundaries, reducing lot sizes for building homes, and so on. Open Space Districts were created in several parts of the state specifically to obtain, manage, and preserve undeveloped land. For example, in the San Francisco Bay Area, the open space districts have created a nearly contiguous range of permanently undeveloped land running through the coastal range and hills surrounding the Bay's urban valleys, enabling the creation of huge natural parks and envisioning a hiking trail that will eventually circumnavigate the Bay in an unbroken loop.

The immense problem with air pollution (smog) that had developed by the early 1970s also caused a backlash. With schools being closed routinely in urban areas for "smog days" when the ozone levels became too unhealthy and the hills surrounding urban areas seldom visible even within a mile, Californians were ready for changes. Over the next three decades, California enacted some of the strictest anti-smog regulations in the United States and has been a leader in encouraging nonpolluting strategies for various industries, including automobiles. For example, carpool lanes normally allow only vehicles with two/three or more occupants (whether the base number is two or three depends on what freeway you are on), but electric cars can use the lanes with only a single occupant. As a result, smog is significantly reduced from its peak, although local Air Quality Management Districts still monitor the air and generally encourage people to avoid polluting activities on hot days when smog is expected to be at its worst.

Traffic and transportation remain a problem in urban areas. Solutions are implemented, but inevitably the implementation expense and the time required to plan, approve, and build infrastructure can't keep pace with the population growth. There have been some improvements. Carpool lanes have become common in urban areas, which are intended to encourage people to drive together rather than in individual automobiles. San Jose is gradually building a light rail system (ironically, often over routes of an original turn-of-the-century electric railroad line that was torn out and paved over to encourage the advent of the automobile age). None of the implemented solutions are without their critics. The sprawling nature of the Bay Area and of the Los Angeles Basin makes it difficult to build mass transit that can reach and serve a significant portion of the population.

In the 1970s, the end of the wars in southeast Asia inspired a new wave of newcomers from those countries, especially Viet Nam, many of whom settled in California. Most worked hard and lived under difficult circumstances. Little Saigons were established in Westminster and Garden Grove in Orange County.

The California legal revolution

During the 1960s, under the aegis of Chief Justice Roger J. Traynor, California became liberal and progressive, emphasizing the rights of defendants even as the crime rate soared. Traynor's term as Chief Justice (from 1964 to 1970) was marked by a number of firsts: California was the first state to create true strict liability in product liability cases, the first to allow the action of negligent infliction of emotional distress (NIED) even in the absence of physical injury to the plaintiff, and the first to allow bystanders to sue for NIED where the only physical injury was to a relative.

Starting in the 1960s, California became a leader in family law. California was the first state to allow true no-fault divorce, with the passage of the Family Law Act of 1969. In 1994, the Legislature took family law out of the Civil Code and created a new Family Code. In 2002, the Legislature granted registered domestic partners the same rights under state law as married spouses (although domestic partners are still treated as unmarried cohabitants for many purposes by federal law).

Since the mid-1980s, the California Supreme Court has become more conservative, particularly with regard to the rights of criminal defendants. This is commonly seen as a reaction against the strict anti-death penalty stance of Chief Justice Rose Bird in the early 1980s, which she maintained even as violent crime soared to record heights statewide. The state's outraged electorate responded by removing her (and two of her anti-death penalty allies) from the court in November of 1986.

High-tech expansion

Starting in the 1950s, high technology companies in Northern California began a spectacular growth that continued through the end of the century. The major products included personal computers, video games, and networking systems. The majority of these companies settled along a highway stretching from Palo Alto to San Jose, notably including Santa Clara and Sunnyvale, California, all in the Santa Clara Valley, the so-called "Silicon Valley," named after the material used to produce the integrated circuits of the era. This era peaked in 2000, by which time demand for skilled technical professionals had become so high that the high-tech industry had trouble filling all of its positions and therefore pushed for increased visa quotas so that they could recruit from overseas. When the "Dot-Com bubble" burst in 2001, jobs evaporated overnight and, for the first time over the next two years, more people moved out of the area than moved in. This somewhat mirrored the collapse of the aerospace industry in southern California some twenty years earlier.

By 2004, it seemed that many of the coveted high-tech jobs were either "off-shored" to India at ten percent of the labor costs in the U.S., or "on-shored" by recruiting newcomers from among the billions in India and China. New laws have removed caps to visas, especially since the adoption of NAFTA. Tens of millions of people from the third world have entered the U.S. since 1960, settling at first mainly in California and the Southwest, but now throughout the continent. In 1960 (when the birth rate nearly equaled the replacement rate) the population of the U.S. was 180 million; in 2000, it was 280 million. By 2010, Hispanics might well be the majority of the population residing in California alone.

A victim of its own success?

Although the air and pollution problems have become less visible because of new laws, health problems associated with pollution have continued to rise. The brown haze associated with nitrogen oxide from automobiles may have abated somewhat, but amounts of deadly ozone have grown. Respiratory allergies are near universal, and asthma is widespread. The crystal clear blue skies — trademarks of California 100 years ago — are long gone. Pollution from storm water drains began to kill organisms near the inhabited seacoast, inspiring numerous conservation organizations. The former paradisiacal lagoons at creek mouths along the coast have disappeared under urban building projects.

In the 1980s, power problems were again predicted, since nuclear power plants that had been projected were not built. Although California still had more power than it needed, executives of utility companies which were owned by or which associated with Enron allegedly conspired to artificially limit electricity supply in the state. The result in the spring and summer of 2000 was chaotic real-time manipulation of electricity distribution by commercial power utilities, manifested primarily in the rolling blackouts used by electricity providers such as Southern California Edison and Pacific Gas and Electric Company to prevent demand from exceeding supply. The issue has not been resolved as of 2004.

In the 1990s, a deadly (to grapevines, at least) phylloxera epidemic swept through California vineyards, devastating wine grapes, and causing billions of dollars of damage.

Still, the ongoing demand for skilled workers over the decades continues in the new millennium. Housing prices in urban areas have continued to increase at a pace faster than almost anywhere in the country, with occasional slow-downs or brief reversals during times of economic slow-down (Silicon Valley in the early 2000s seems to be an exception, with housing prices continuing to rise although unemployment is over 8%). An average home that, in the 1960s, cost $25,000, now costs half a million dollars or more in urban areas, such as in the San Francisco Bay Area and parts of the Los Angeles and San Diego regions. More people commute longer hours to afford a home in more rural areas while earning larger salaries in the urban areas.

Third millennium politics

In the 2002 gubernatorial campaign, Democratic incumbent Gray Davis defeated challenger Bill Simon with a plurality of 47.4%. Days after the election, Davis was accused of having hidden a record $34.6 billion budget deficit. Davis' approval rating dropped to 24%, the lowest ever in the history of the California Field Poll. Nearly two million Californians signed petitions calling for a recall election against Davis. The effort against Davis marked the first time since the 1911 inclusion of a recall clause into the State Constitution that a California governor faced a recall election. There had been 31 attempts in that time.

There were two parts to the recall ballot. The first part asked whether Davis should be recalled. The second part asked, if the recall occurred, which candidate other than Davis should be the new governor. 135 candidates ran to replace Davis.

On October 7, 2003, Davis was successfully recalled, with 55.4% of the voters supporting the recall (see results of the 2003 California recall). With a plurality of 48.6% of the vote, Republican Arnold Schwarzenegger was chosen as the new governor. Lieutenant Governor Cruz Bustamante received 31.5% of the vote, and Republican State Senator Tom McClintock received 13.5% of the vote.

Schwarzenegger began his shortened term with a soaring approval rating and soon after began implementing a conservative agenda. This initially resulted in sparring with the heavily Democratic Assembly and Senate over the state budget, battles which provided his infamous "girly men" comment but also began taking their toll on his approval rating. Schwarzenegger then embarked on a campaign to enact several ballot propositions in a 2005 Special Election touted as reforming California's budget system, redistricting powers, and union political fundraising. The union-led campaign spearheaded by the California Nurses Association contributed heavily to the defeat of every proposition in the Special Election. Since this conspicuous failure, Schwarzenegger has made a turn back to the left, criticizing the Bush Administration at many junctures, reviving his environmental agenda, and compromising with the legislature on the traditionally Democratic issue of education spending. His approval rating has also been revived, and was re-elected.

Bibliography

Surveys

- Bakken, Gordon Morris. California History: A Topical Approach (2003)

- Robert W. Cherny, Richard Griswold del Castillo, and Gretchen Lemke-Santangelo. Competing Visions: A History Of California (2005)

- Merchant, Carolyn ed. Green Versus Gold: Sources In California's Environmental History (1998) readings in primary and secondary sources

- Pitt, Leonard, and Dale Pitt. Los Angeles A to Z: An Encyclopedia of the City and County (2000)

- Rawls, James J. ed. New Directions In California History: A Book of Readings (1988)

- Rawls, James and Walton Bean (2003). California: An Interpretive History. ISBN 0-07-052411-4. 8th edition

- Rice, Richard B., William A. Bullough, and Richard J. Orsi. Elusive Eden: A New History of California 3rd ed (2001)

- Rolle, Andrew F. California: A History 6th ed. (2003)

- Starr, Kevin and Richard J. Orsi eds. Rooted in Barbarous Soil: People, Culture, and Community in Gold Rush California (2001)

- Starr, Kevin. (Note that there are numerous editions of this monumental state history, with slight title changes)

- Starr, Kevin California: A History (2005), synthesis

- Americans and the California Dream, 1850-1915 (1973)

- Inventing the Dream: California through the Progressive Era (1986)

- Material Dreams: Southern California through the 1920s(1991)

- Endangered Dreams : The Great Depression in California (1997)

- The Dream Endures: California Enters the 1940s (1997)

- Embattled Dreams: California in War and Peace, 1940-1950 (2003)

- Coast of Dreams: California on the Edge, 1990-2003 (2004)

- Sucheng, Chan , and Spencer C. Olin, eds. Major Problems in California History (1996)

1846-1900

- Brands, H.W. The Age of Gold: The California Gold Rush and the New American Dream (2003)

- Burchell, Robert A. "The Loss of a Reputation; or, The Image of California in Britain before 1875," California Historical Quarterly 53 (Summer I974): 115-30, stories about Gold Rush lawlessness slowed immigration for two decades

- Burns, John F. and Richard J. Orsi, eds; Taming the Elephant: Politics, Government, and Law in Pioneer California U. of California Press, (2003) [online edition

- Jelinek, Lawrence. Harvest Empire: A History of California Agriculture (1982)

- McAfee, Ward. California's Railroad Era, 1850-1911 (1973)

- Olin, Spencer. California Politics, 1846-1920 (1981)

- Pitt, Leonard. The Decline of the Californios: A Social History of the Spanish-Speaking Californians, 1846-1890 (1966) (ISBN 0-520-01637-8)

- Saxton, Alexander. The Indispensable Enemy: Labor and the Anti-Chinese Movement in California (1971) (ISBN 0-520-02905-4)

- Starr, Kevin. Americans and the California Dream, 1850-1915 (1986)

- Starr, Kevin and Richard J. Orsi eds. Rooted in Barbarous Soil: People, Culture, and Community in Gold Rush California (2001), articles by scholars

- Tutorow , Norman E. Leland Stanford Man of Many Careers(1971)

- Williams, R. Hal. The Democratic Party and California Politics, 1880-1896 (1973)

1900-2007

- Abelmann, Nancy, and John Lie. Blue Dreams: Korean Americans and the Los Angeles Riots (1995)

- Fogelson, Robert M. The Fragmented Metropolis: Los Angeles, 1850-1930 (1993)

- Miller, Sally M., and Daniel A. Cornford eds. American Labor in the Era of World War II (1995) essays by scholars, mostly on California

- Roger W. Lotchin. Fortress California, 1910-1961 (2002)

- George E. Mowry. The California Progressives (1963)

- Sackman. Douglas Cazaux. Orange Empire: California and the Fruits of Eden. (2005) comprehensive, multidimensional history of citrus industry

- Stephanie S. Pincetl. Transforming California: A Political History of Land Use and Development (2003)

- Sitton, Tom and William F, Deverell, eds. Metropolis in the Making: Los Angeles in the 1920s (2001)

- Danielle Jean Swiontek. With Ballots and Pocketbooks: Women, Labor, and Reform in Progressive California (2006)