Korematsu v. United States: Difference between revisions

imported>Shamira Gelbman |

imported>Shamira Gelbman (→Opinion of the Court: Hirabayashi precedent) |

||

| Line 28: | Line 28: | ||

=== Opinion of the Court === | === Opinion of the Court === | ||

Justice [[Hugo Black]] wrote the opinion of the Court, which acknowledged at the outset that "all legal restrictions which curtail the civil rights of a single racial group are immediately suspect,"<ref>323 U.S. 216</ref> but concluded that "to cast this case into outlines of racial prejudice, without reference to the real military dangers which were presented, merely confuses the issue."<ref>323 U.S. 223</ref> | Justice [[Hugo Black]] wrote the opinion of the Court, which acknowledged at the outset that "all legal restrictions which curtail the civil rights of a single racial group are immediately suspect,"<ref>323 U.S. 216</ref> but concluded that "to cast this case into outlines of racial prejudice, without reference to the real military dangers which were presented, merely confuses the issue."<ref>323 U.S. 223</ref> | ||

In upholding the federal government's power to authorize wartime curfews and exclusion orders, the opinion relied heavily upon the ruling in the first Supreme Court case challenging the Japanese internment, [[Hirabayashi v. United States]].<ref>323 U.S. 81 (1943)</ref> | |||

=== Concurring and dissenting opinions === | === Concurring and dissenting opinions === | ||

Revision as of 16:07, 11 March 2009

Korematsu v. United States was a controversial United States Supreme Court case, decided in 1944, that upheld the Japanese internment during World War II.[1] The case has been cited as an unprecedented example of racial prejudice and the erosion of individual liberties during wartime in the United States.

Historical context

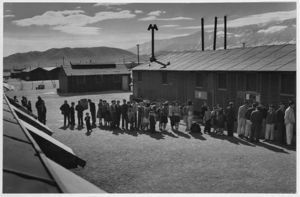

The December 7, 1941 attack by Japan on Pearl Harbor prompted widespread concern about the security of the United States' West Coast and the possibility of espionage by members of its large Japanese-American population. On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt responded by issuing Executive Order (EO) 9066, which authorized the Secretary of War and his designated commanders to establish "military areas" as they see fit and exclude "any or all persons" from entering or remaining within them.[2] The main result of Roosevelt's order was the relocation of more than 100,000 Americans of Japanese descent from the West Coast into internment camps in the interior of the United States. A month later, Congress passed Public Law 503, which criminalized violations of military orders issued as a result of EO 9066.

Facts of the case

Persuant to EO 9066, on May 3, 1942, the U.S. army issued Civilian Exclusion Order Number 34, which instructed all persons of Japanese ancestry living in San Leandro, California to evacuate the area by the end of that week. Fred Korematsu, a California-born American citizen whose parents had emigrated from Japan in 1905, refused to comply with the exclusion order.

Korematsu was apprehended on May 30, 1942 and subsequently tried and found to be in violation of Public Law 503 by the Federal District Court for Northern California. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the district court ruling. Korematsu appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which granted certiorari on March 27, 1944. Oral arguments were heard on October 11, 1944.

Decision

On December 18, 1944, the Supreme Court ruled, 6-3, to affirm the lower courts' decisions and uphold the Japanese internment as a constitutional exercise of executive and legislative power.

Opinion of the Court

Justice Hugo Black wrote the opinion of the Court, which acknowledged at the outset that "all legal restrictions which curtail the civil rights of a single racial group are immediately suspect,"[3] but concluded that "to cast this case into outlines of racial prejudice, without reference to the real military dangers which were presented, merely confuses the issue."[4]

In upholding the federal government's power to authorize wartime curfews and exclusion orders, the opinion relied heavily upon the ruling in the first Supreme Court case challenging the Japanese internment, Hirabayashi v. United States.[5]

Concurring and dissenting opinions

Justice Felix Frankfurter authored a concurring opinion.

Three justices, Owen Roberts, Robert Jackson, and Frank Murphy each filed a separate dissenting opinion. Murphy's dissent was especially scathing, famously commenting that the majority decision "falls into the ugly abyss of racism."

Aftermath

Today, this decision is widely criticized and denounced as a classic example of wartime encroachment on civil liberties. The Congress passed the Japanese American Evacuation Claims Act to provide compensation to Japanese properties damaged during the "relocation". In 1980 the Congress opened an investigation to the internment program and a report titled "Personal Justice Denied" was written. The report condemned the "relocation" and the Korematsu court decision. In 2001, the PBS broadcast a Eric Paul Fournier film Of Civil Wrongs and Rights in memory of the Japanese internment and the Korematsu litigation. In 1998, Fred Korematsu was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Bill Clinton; he died in 2005.

Tom Clark, the coordinator of the relocation program, was nominated to became a Supreme Court justice in 1949. He said he regretted his role in the Japanese internment and referred to it as one of his biggest mistakes. When Clark resigned from the Court in 1967, he was replaced by the first black Justice, Thurgood Marshall.

Sources

- ↑ Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214 (Supreme Court of the United States December 18, 1944)

- ↑ "Executive Order 9066: Authorizing the Secretary of War to Prescribe Military Areas," February 19, 1942, [1]

- ↑ 323 U.S. 216

- ↑ 323 U.S. 223

- ↑ 323 U.S. 81 (1943)