Sine: Difference between revisions

imported>Paul Wormer |

imported>Paul Wormer |

||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

!--> | !--> | ||

==Geometric approach== | ==Geometric approach== | ||

In | In most countries, schoolchildren begin to study mathematics with arithmetics, elementary [[algebra]] and 2-dimensional [[Euclidean geometry]] (plane geometry). <ref name="kiselev"> | ||

{{cite book | {{cite book | ||

|author=A.P.Kiselev | |author=A.P.Kiselev | ||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

}}</ref>. | }}</ref>. | ||

<!-- http://www.sumizdat.org/ !--> | <!-- http://www.sumizdat.org/ !--> | ||

When they learn about sin and cos, the students already have some idea about addition and measurement of [[angle]]s, segments and areas; they already have accepted [[Euclid's elements|the axioms of Euclid]], in particular his famous fifth [[Euclid's parallel axiom|parallel axiom]], and they know the [[Pythagorean theorem]]. Therefore, the trigonometric functions are '''defined''' as ratios of the lengths of sides of the [[right-angled triangle]]s, for example, the ratio of the length of a [[leg(geometry)|leg]] to that of the [[hypothenuse]]. We will outline this approach, but point out that an alternative approach is possible which does not rely on Euclid's axioms. This approach, which is more advanced in that it needs some knowledge of differential calculus, will be given in the next sextion. | |||

===Definition of sine and cosine in plane geometry=== | |||

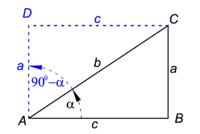

[[Image:Def sine cosine.png|right|thumb|200px|Fig .1. Acute angle α is ∠CAB; ∠CBA = 90°.]] | |||

The most elementary definition of the functions '''sine''' and '''cosine''' follows from Fig. 1. We see a right-angled triangle ABC (black) with an acute angle α. By definition sinα is equal to the the length ''a'' of the side opposite angle α divided by the [[hypotenuse]], which has length ''b''. The cosine of α is the length ''c'' of the side adjacent to α divided by the length of the hypotenuse ''b'': | |||

:<math> | |||

\sin\alpha\, \stackrel{\mathrm{def}}{=}\, \frac{a}{b}, \qquad \cos\alpha\, \stackrel{\mathrm{def}}{=}\, \frac{c}{b}. | |||

</math> | |||

Applying the same definitions to the complementary angle ∠DAC (= 90°−α) we find from the dashed blue triangle in Fig. 1, | |||

:<math> | |||

\sin(90^\circ-\alpha) = \cos\alpha= \frac{c}{b},\qquad\cos(90^\circ-\alpha) = \sin\alpha= \frac{a}{b}. | |||

</math> | |||

We see that for complementary angles the functions sine and cosine are interchanged, hence the name "cosine" (short for "complementary sine"). | |||

The [[Pythagorean theorem]] states that ''b''<sup>2</sup> = ''a''<sup>2</sup>+''c''<sup>2</sup>, so that we get the following important relation between the sine and the cosine functions | |||

:<math> | |||

(\sin\alpha)^2 + (\cos\alpha)^2 = \frac{a^2}{b^2}+ \frac{c^2}{b^2}= \frac{a^2+c^2}{b^2} = \frac{b^2}{b^2}=1. | |||

</math> | |||

Since this elementary definition of sine and cosine is in terms of ratios of lengths, which are positive, the definition needs to be generalized in order to account for negative function values. | |||

===Cartesian definition=== | |||

We recall that a vector '''r''' in a 2-dimensional plane can be represented by two [[Cartesian coordinates]], which are [[real number]]s: '''r''' = (''x'', ''y''). These numbers are the projections of '''r''' on the ''x''- and the ''y''-axis, respectively. The ''length'' of '''r''' is denoted by |'''r'''| and is defined by | |||

:<math> | |||

|\mathbf{r}| \, \stackrel{\mathrm{def}}{=}\, \sqrt{x^2+y^2}. | |||

</math> | |||

Assuming that the length of '''r''' is non-zero we can divide the components of the vector by it and obtain a ''unit vector'' '''e'''<sub>''r''</sub>, which by definition has length unity. Unit vectors in the plane have their endpoints on a unit circle (circle with unit radius). | |||

Consider Fig. 1 again. Assume now that the length ''b'' equals 1, then the vector '''e'''<sub>AC</sub> pointing from point A to point C is a unit vector. Assume a Cartesian system of axes with the origin in A and let the ''x''-axis be along A–B and the ''y''-axis be along A–D. Clearly cosα = ''c'' is the projection of '''e'''<sub>AC</sub> on the ''x''-axis, i.e., cosα = ''c'' is the ''x''-coordinate of this unit vector. Similarly sinα = ''a'' is the ''y'' coordinate of the unit vector. This observation leads to the following definition, which is a generalization of the earlier one. | |||

Write '''e'''<sub>''x''</sub> for a unit vector on the ''x''-axis and '''e'''<sub>''y''</sub> for a unit vector on the ''y''-axis. | |||

'''Definition''': If '''e''' is a unit vector obtained from '''e'''<sub>''x''</sub> by a positive (counter-clockwise) rotation over the angle α, then cosα is the ''x'' coordinate of '''e''' and sinα is the ''y'' coordinate of '''e''': | |||

:<math> | |||

\mathbf{e}\, \stackrel{\mathrm{def}}{=}\, \cos\alpha\,\mathbf{e}_x + \sin\alpha\,\mathbf{e}_y, \qquad |\mathbf{e}| \equiv 1 = (\cos\alpha)^2 + (\sin(\alpha)^2. | |||

</math> | |||

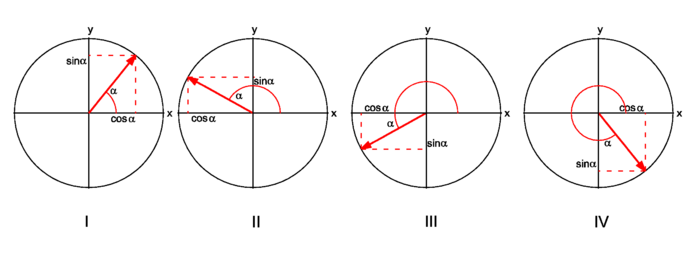

The unit vector '''e''' is depicted (as a red vector with endpoint on the unit circle) in the four different quadrants in Fig. 2. | |||

<br> | |||

[[Image:Sign sincos.png|right|thumb|700px|Fig. 2. Unit vector '''e''' (shown in red) in different quadrants. Projection on ''x''-axis is cos α, projection on ''y''-axis is sin α.]] | |||

<div align="left"> | |||

<table width="25%"> | |||

<tr><td colspan="4"> <hr> </td></tr> | |||

<tr><td colspan="4" align="center"> | |||

<b>Signs of sine and cosine</b> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr><td colspan="4"> <hr> </td></tr> | |||

<tr><td>Quadrant </td> | |||

<td>Range α </td> | |||

<td align="left">cos</td> | |||

<td align="left">sin</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr><td colspan="4"> <hr> </td></tr> | |||

<tr><td>I <td> 0<sup>0</sup>< α < 90<sup>0</sup> <td>+<td>+</tr> | |||

<tr><td>II <td> 90<sup>0</sup>< α < 180<sup>0</sup> <td>−<td>+</tr> | |||

<tr><td>III <td>180<sup>0</sup>< α < 270<sup>0</sup> <td>−<td>−</tr> | |||

<tr><td>IV <td>270<sup>0</sup>< α < 360<sup>0</sup> <td>+<td>−</tr> | |||

</table> | |||

</div> | |||

<br><br><br><br><br> | |||

Clearly, if α=0° then '''e''' = '''e'''<sub>''x''</sub>. If α=90° then '''e''' = '''e'''<sub>''y''</sub>. If α=180° then '''e''' = −'''e'''<sub>''x''</sub>. Thus, | |||

:<math> | |||

\begin{align} | |||

\cos 0^\circ &= 1, & \sin 0^\circ &= 0\\ | |||

\cos 90^\circ &= 0, & \sin 90^\circ &= 1 \\ | |||

\cos180^\circ &= -1, & \sin180^\circ &= 0 | |||

\end{align} | |||

</math> | |||

It is also clear from the definition that, when α is rotated over more than 360°, the unit vector is back at an angle between 0° and 360°. Therefore, for positive integer ''k'', | |||

:<math> | |||

\cos(\alpha + 360^\circ\sdot k) = \cos(\alpha),\qquad\sin(\alpha + 360^\circ\sdot k) = \sin(\alpha). | |||

</math> | |||

Negative angles are defined by rotating the unit vector ''clockwise''. By definition reflection in the ''x''-axis changes the components of the unit vector thus, | |||

:<math> | |||

x\mapsto x, \qquad y \mapsto -y | |||

</math> | |||

Further one sees easily that α is mapped to −α under this reflection. That is, upon reflection α and the ''y''-coordinate change sign and the ''x''-coordinate is invariant (stays the same), hence | |||

:<math> | |||

\sin(-\alpha) = -\sin(\alpha), \qquad \cos(-\alpha) = \cos(\alpha). | |||

</math> | |||

When one rotates the unit vector clockwise over more than 360° one arrives again at a position between 0° and 360°, so that for positive integer ''k'', | |||

:<math> | |||

\cos(\alpha - 360^\circ\sdot k) = \cos(\alpha),\qquad\sin(\alpha - 360^\circ\sdot k) = \sin(\alpha). | |||

</math> | |||

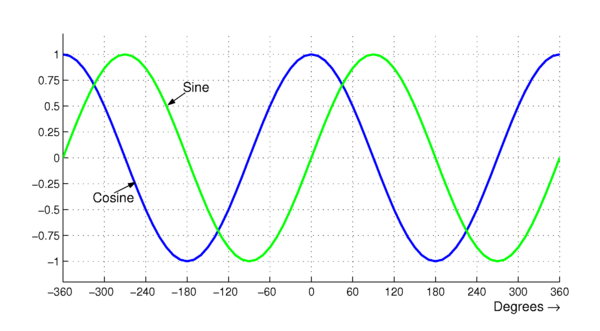

By standard arguments of plane [[Euclidean geometry]] one can compute the numerical values of sine and cosine for a few specific angles. The application of differential calculus (see later in this article) allows the computation of the function values for ''all'' angles. Thus, one obtains the graphs shown in Fig. 3. | |||

[[Image:Sine and cosine.png|center|thumb|600px|Fig. 3. The functions sin(''x'') and cos(''x'') for ''x'' running from −360° to 360°]] | |||

===Sum formulas=== | |||

The following equations hold: | |||

:<math> | |||

\begin{align} | |||

\cos(\alpha+\beta) &= \cos\alpha\cos\beta - \sin\alpha\sin\beta\\ | |||

\sin(\alpha+\beta) &= \sin\alpha\cos\beta+\cos\alpha\sin\beta | |||

\end{align} | |||

</math> | |||

'''Proof''' | |||

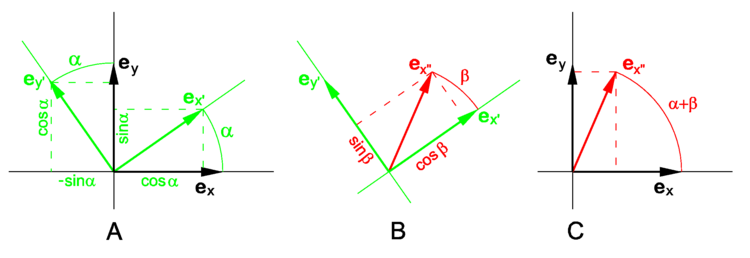

[[Image:Sum angles.png|center|thumb|750px| Fig. 4A: Rotated (green) unit vectors <font color="green"> | |||

'''e'''<sub>''x'' ′</sub></font> and <font color="green"> | |||

'''e'''<sub>''y'' ′</sub></font> expressed in original (black) unit vectors '''e'''<sub>''x''</sub> and '''e'''<sub>''y''</sub>. <br> | |||

Fig. 4B: Rotated (red) unit vector <font color="red"> | |||

'''e'''<sub>''x'' "</sub></font> expressed with respect to the primed (green) vectors. <br> | |||

Fig. 4C: The vector <font color="red">'''e'''<sub>''x'' "</sub></font> expressed with respect to the unprimed (black) vectors]] | |||

The proof is easiest in matrix notation. Because we do not expect readers to know this notation we give the proof in long-hand notation and only indicate briefly the equivalent matrix form. The unit vectors and angles that play a role in the proof are depicted in Fig. 4. | |||

As shown in Fig. 4A, the singly primed (green) unit vectors are given in terms of the unprimed (black) unit vectors by | |||

:<math> | |||

\begin{align} | |||

\mathbf{e}_{x'} &= \cos\alpha\,\mathbf{e}_{x} + \sin\alpha\, \mathbf{e}_{y} \\ | |||

\mathbf{e}_{y'} &= -\sin\alpha\,\mathbf{e}_{x} + \cos\alpha\, \mathbf{e}_{y} | |||

\end{align} | |||

\quad \Longleftrightarrow\quad | |||

\begin{pmatrix}\mathbf{e}_{x'}\\ \mathbf{e}_{y'}\end{pmatrix}= | |||

\begin{pmatrix}\cos\alpha & \sin\alpha\\ -\sin\alpha& \cos\alpha \end{pmatrix} | |||

\begin{pmatrix}\mathbf{e}_{x}\\ \mathbf{e}_{y}\end{pmatrix} | |||

</math> | |||

In Fig. 4B the doubly primed (red) unit vector '''e'''<sub>''x'' "</sub> is given in terms of the singly primed (green) unit vectors by | |||

:<math> | |||

\mathbf{e}_{x''} = \cos\beta\,\mathbf{e}_{x'} + \sin\beta\, \mathbf{e}_{y'} | |||

\quad \Longleftrightarrow\quad\mathbf{e}_{x''} = | |||

(\cos\beta,\,\,\sin\beta) \begin{pmatrix}\mathbf{e}_{x'}\\ \mathbf{e}_{y'}\end{pmatrix} | |||

</math> | |||

In Fig. 4C the doubly primed (red) vector '''e'''<sub>''x'' "</sub> is given in terms of the unprimed (black) vectors: | |||

:<math> | |||

\mathbf{e}_{x''} = \cos(\alpha+\beta)\,\mathbf{e}_{x} + \sin(\alpha+\beta)\, \mathbf{e}_{y} | |||

\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad \qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad (1) | |||

</math> | |||

Substitution of the expression for the singly primed unit vectors (green) in terms of the unprimed vectors (black) into the expression for '''e'''<sub>''x'' "</sub> gives : | |||

:<math> | |||

\mathbf{e}_{x''} = \cos\beta( \cos\alpha\,\mathbf{e}_{x}+ \sin\alpha\,\mathbf{e}_{y}) | |||

+\sin\beta(-\sin\alpha\,\mathbf{e}_{x} +\cos\alpha\,\mathbf{e}_{y}) | |||

</math> | |||

Upon rearranging, | |||

:<math> | |||

\mathbf{e}_{x''} = (\cos\alpha\cos\beta - \sin\alpha\sin\beta)\,\mathbf{e}_{x} + (\sin\alpha\cos\beta+\cos\alpha\sin\beta)\,\mathbf{e}_{y} | |||

\qquad\qquad\qquad (2) | |||

</math> | |||

(In matrix notation the last two expression are equivalent to the multiplication of a row vector with a square matrix). Putting Eqs. (1) and (2) for '''e'''<sub>''x'' "</sub> in terms of the unprimed unit vectors side by side, we find the equations to be proved. This conclusion is allowed because '''e'''<sub>''x'' </sub> and '''e'''<sub>''y'' </sub> are linearly independent. | |||

<font color="green"> | |||

<!-- | |||

The geometrical approach rather assumes properties of sin and cos than deduce them. The assumptions are masked as the geometric axioms. However the deduction of properties of trigonometric functions does not require axioms of geometry. Properties of sin and cos do not depend, for example, on the acceptance of rejection of the [[Euclid's parallel axiom]]. Funcitons sin and cos can be defined algebraically, then their properties can be deduced, not postulated. | The geometrical approach rather assumes properties of sin and cos than deduce them. The assumptions are masked as the geometric axioms. However the deduction of properties of trigonometric functions does not require axioms of geometry. Properties of sin and cos do not depend, for example, on the acceptance of rejection of the [[Euclid's parallel axiom]]. Funcitons sin and cos can be defined algebraically, then their properties can be deduced, not postulated. | ||

Basic elements of such a deduction are suggested below. | Basic elements of such a deduction are suggested below. | ||

--> | |||

==Definition by differential equations== | ==Definition by differential equations== | ||

Revision as of 03:51, 7 November 2008

sine and cosine, abbreviated sin and cos, are basic trigonometric functions (which are, in their turn, basic elementary functions), used to express relations between angles and sides of right triangles). These functions are common in science and technology.

Various sources define trigonometric funcitons in different ways.

Geometric approach

In most countries, schoolchildren begin to study mathematics with arithmetics, elementary algebra and 2-dimensional Euclidean geometry (plane geometry). [1]. When they learn about sin and cos, the students already have some idea about addition and measurement of angles, segments and areas; they already have accepted the axioms of Euclid, in particular his famous fifth parallel axiom, and they know the Pythagorean theorem. Therefore, the trigonometric functions are defined as ratios of the lengths of sides of the right-angled triangles, for example, the ratio of the length of a leg to that of the hypothenuse. We will outline this approach, but point out that an alternative approach is possible which does not rely on Euclid's axioms. This approach, which is more advanced in that it needs some knowledge of differential calculus, will be given in the next sextion.

Definition of sine and cosine in plane geometry

The most elementary definition of the functions sine and cosine follows from Fig. 1. We see a right-angled triangle ABC (black) with an acute angle α. By definition sinα is equal to the the length a of the side opposite angle α divided by the hypotenuse, which has length b. The cosine of α is the length c of the side adjacent to α divided by the length of the hypotenuse b:

Applying the same definitions to the complementary angle ∠DAC (= 90°−α) we find from the dashed blue triangle in Fig. 1,

We see that for complementary angles the functions sine and cosine are interchanged, hence the name "cosine" (short for "complementary sine").

The Pythagorean theorem states that b2 = a2+c2, so that we get the following important relation between the sine and the cosine functions

Since this elementary definition of sine and cosine is in terms of ratios of lengths, which are positive, the definition needs to be generalized in order to account for negative function values.

Cartesian definition

We recall that a vector r in a 2-dimensional plane can be represented by two Cartesian coordinates, which are real numbers: r = (x, y). These numbers are the projections of r on the x- and the y-axis, respectively. The length of r is denoted by |r| and is defined by

Assuming that the length of r is non-zero we can divide the components of the vector by it and obtain a unit vector er, which by definition has length unity. Unit vectors in the plane have their endpoints on a unit circle (circle with unit radius).

Consider Fig. 1 again. Assume now that the length b equals 1, then the vector eAC pointing from point A to point C is a unit vector. Assume a Cartesian system of axes with the origin in A and let the x-axis be along A–B and the y-axis be along A–D. Clearly cosα = c is the projection of eAC on the x-axis, i.e., cosα = c is the x-coordinate of this unit vector. Similarly sinα = a is the y coordinate of the unit vector. This observation leads to the following definition, which is a generalization of the earlier one.

Write ex for a unit vector on the x-axis and ey for a unit vector on the y-axis.

Definition: If e is a unit vector obtained from ex by a positive (counter-clockwise) rotation over the angle α, then cosα is the x coordinate of e and sinα is the y coordinate of e:

The unit vector e is depicted (as a red vector with endpoint on the unit circle) in the four different quadrants in Fig. 2.

| | |||

|

Signs of sine and cosine | |||

| | |||

| Quadrant | Range α | cos | sin |

| | |||

| I | 00< α < 900 | + | + |

| II | 900< α < 1800 | − | + |

| III | 1800< α < 2700 | − | − |

| IV | 2700< α < 3600 | + | − |

Clearly, if α=0° then e = ex. If α=90° then e = ey. If α=180° then e = −ex. Thus,

It is also clear from the definition that, when α is rotated over more than 360°, the unit vector is back at an angle between 0° and 360°. Therefore, for positive integer k,

Negative angles are defined by rotating the unit vector clockwise. By definition reflection in the x-axis changes the components of the unit vector thus,

Further one sees easily that α is mapped to −α under this reflection. That is, upon reflection α and the y-coordinate change sign and the x-coordinate is invariant (stays the same), hence

When one rotates the unit vector clockwise over more than 360° one arrives again at a position between 0° and 360°, so that for positive integer k,

By standard arguments of plane Euclidean geometry one can compute the numerical values of sine and cosine for a few specific angles. The application of differential calculus (see later in this article) allows the computation of the function values for all angles. Thus, one obtains the graphs shown in Fig. 3.

Sum formulas

The following equations hold:

Proof

The proof is easiest in matrix notation. Because we do not expect readers to know this notation we give the proof in long-hand notation and only indicate briefly the equivalent matrix form. The unit vectors and angles that play a role in the proof are depicted in Fig. 4.

As shown in Fig. 4A, the singly primed (green) unit vectors are given in terms of the unprimed (black) unit vectors by

In Fig. 4B the doubly primed (red) unit vector ex " is given in terms of the singly primed (green) unit vectors by

In Fig. 4C the doubly primed (red) vector ex " is given in terms of the unprimed (black) vectors:

Substitution of the expression for the singly primed unit vectors (green) in terms of the unprimed vectors (black) into the expression for ex " gives :

Upon rearranging,

(In matrix notation the last two expression are equivalent to the multiplication of a row vector with a square matrix). Putting Eqs. (1) and (2) for ex " in terms of the unprimed unit vectors side by side, we find the equations to be proved. This conclusion is allowed because ex and ey are linearly independent.

Definition by differential equations

The definitions of derivative and integral do not refer to trigonometric functions, and the basic properties of integrals and derivatives (in particular the Cauchy-Kowalevski theorem of existence and uniqueness of solution of the Cauchy problem) can be deduced without reference to sin, cos, or any axioms of Euclidean geometry. Therefore, a natural and consistent way of defining the functions sin and cos is via differential equations. We will indicate the first derivative of a function with respect to its variable by a prime.

Definition

The functions sin and cos are solutions of the following system of equations

- (1)

- (2)

with conditions

- (3)

- (4)

Usually, it is assumed that the independent variable t is real; in that case, the values of the functions sin and cos are also real numbers. However, the definition above can be used for complex numbers too.

The present definition does not imply additional concepts about angles and sums of angles; and does not require the Pythagorean theorem or even the parallel axiom of Euclidean geometry. Furthermore the definition does not refer to the concept of the number Pi () and therefore can be used for the definition of . But, one pays for this by having to deduce the naively-obvious properties of sin and cos from the system (1)–(4).

Sum of squares

Consider the function . From equations (1) and (2) it follows that , i.e., constant . Evaluation of this constant from equations (2) and (3) gives for all , i.e.,

- (5)

In this article, the superscript as indicator of exponentiation is always written last to specify the argument, avoiding the confusions. [2]

For the equation (5) it follows, that for all real values of t the functions sin(t) and cos(t) are bounded:

- (6)

- (7)

These properties allow efficient bracketing of functions sin and cos.

Bracketing

Consider and in the case . From equation (1) it follows, that . Integration of the last inequality with respect to from 0 to gives: . Using equation (3) we write

- (8) .

Rewrite (8) as and apply equation(2):

Integrating this inequality with respect to from 0 to gives:

Using equation(4) gives

- (9)

The last "<" just follows from equation (7). Using equation (1) gives

- (10)

Integrating equation (12) with respect to from 0 to gives

- (11)

Rewrite it as

and apply equation (2):

Integrating this equation with respect to from 0 to gives

- (12)

Continuing this exercise, one can obtain more and more narrow bounds for values of sin and cos.

However, even equations (9,12) are sufficient to see that both both sin and cos remain positive while, the argument is within (0,1) range. This property is used below to reveal periodicity of these funcitons.

Mathematical induction

Applying the mathematical induction, it is possible to show that for positive integer

- (13)

- (14)

and equality takes place only at .

Is cos always larger than sin?

Consider the range such that both and are positive; let be exact upper bound of such interval. Within this interval, sin is monotonously increasing, and cos is monotonously decreasing. Therefore, there exist one and only one solution of the equation

- (13)

Let us estimate value of this solution.

Consider the special case, substitute into equation(13) and into equation(11). This gives

In such a way,

- (14)

hence,

- (15) .

Substitute into equation (11); this gives

- (16)

- (17)

From equation (5) it follows that

- (18)

- (19)

Both sin and cos are positive in the range (0,1); and, therefore,

- (20)

Therefore,

- (21) .

Symmetry and sense of number

Change of variables to and replacement to keeps the system (1)-(4) invariant. This means that

- (22)

- (23)

Consider replacement to , cos to sin, and sin to cos. Due to equation (13), such a replacement preserves the equations (1-4); therefore,

- (24)

- (25)

Then, , and

- (26)

- (27)

It follows, that functions sin and cos are periodic; and

- (30)

is period. The deduction above can be used as definition of number . In such a way, appears as half of period of functions which are solutions of equations (1,2).

For definition of , equations (1,2) are sufficient: due to the linearity of equations and the translational invariance, conditions (3,4) do not affect the period; all the solutions with different conditions at zero have the same period.

From estimate (21) it follows that

- (31)

The improvement of this estimate using the expansions (13), (14) is possible but computationally non-efficient. The efficient algorithms for evaluation of are mentioned in the spacial article about Pi. Usually, the efficient algorithms require more efforts for the deduction.

Notes

- ↑ A.P.Kiselev (1892 (first efition in Russia)). {{{title}}}. ISBN 0-9779852-0-2.

- ↑ Some authors implicitly define also functions with superscript, and . However, such a notation leads to confusions as soon as one needs to consider the inverse function (for a function , it is common to use notation for inverse function, such that ) or multiple combination of functions, for example: ; .