Ken McGregor: Difference between revisions

imported>Hayford Peirce (world ranking) |

imported>Hayford Peirce (added a footnote) |

||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

As a youth, McGregor was a fine all-round athlete, excelling in cricket, Australian-rules football, and tennis. [[Harry Hopkins]], the face of the Australian [[Davis Cup]] team for many years, induced him to devote himself exclusively to tennis, and as an amateur he was near the very top of game. Besides winning the Australian championship, he lost the 1951 Wimbledon finals to [[Dick Savitt]] and played on three winning Davis Cup teams. By beating the favored Sedgman in the 1952 Australian tournament, he deprived Sedgman of the opportunity to win the coveted Grand Slam of tennis—Sedgman subsequently went on that year to win the three final events. In 1952 he and Sedgman were heavily favored to win their eighth Grand Slam doubles tournament in a row but were shocked in the finals of the United States Open by the pick-up team of the Australian [[Mervyn Rose]] and the American [[Vic Seixas]], two men who had never before played together. | As a youth, McGregor was a fine all-round athlete, excelling in cricket, Australian-rules football, and tennis. [[Harry Hopkins]], the face of the Australian [[Davis Cup]] team for many years, induced him to devote himself exclusively to tennis, and as an amateur he was near the very top of game. Besides winning the Australian championship, he lost the 1951 Wimbledon finals to [[Dick Savitt]] and played on three winning Davis Cup teams. By beating the favored Sedgman in the 1952 Australian tournament, he deprived Sedgman of the opportunity to win the coveted Grand Slam of tennis—Sedgman subsequently went on that year to win the three final events. In 1952 he and Sedgman were heavily favored to win their eighth Grand Slam doubles tournament in a row but were shocked in the finals of the United States Open by the pick-up team of the Australian [[Mervyn Rose]] and the American [[Vic Seixas]], two men who had never before played together. | ||

In the unofficial but authoritative annual ratings of the world's best amateur players by first John Olliff and then Lance Tingay of the London ''Daily Telegraph'', McGregor was ranked no. 8 in 1950, no. 7 in 1951, and no. 3 in 1952. | In the unofficial but authoritative annual ratings of the world's best amateur players by first John Olliff and then Lance Tingay of the London ''Daily Telegraph'', McGregor was ranked no. 8 in 1950, no. 7 in 1951, and no. 3 in 1952.<ref>''Total Tennis:The Ultimate Tennis Encyclopedia,'' by Bud Collins, page 916.</ref> | ||

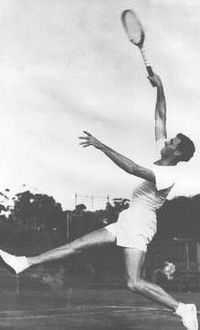

{{Image|McGregor and Rosewall 1952.jpg|left|200px|McGregor, right, with the 18-year-old [[Ken Rosewall]] in 1952.}} | {{Image|McGregor and Rosewall 1952.jpg|left|200px|McGregor, right, with the 18-year-old [[Ken Rosewall]] in 1952.}} | ||

Revision as of 17:02, 9 June 2011

Kenneth Bruce McGregor (June 2, 1929, Adelaide, Australia – December 1, 2007, Myrtle Bank, Australia) was an Australian tennis player who won the Men's Singles of the Australian Open in 1952. He and his longtime partner, Frank Sedgman, are generally considered to be one of the greatest doubles teams of all time.[1] In 1951 and 1952 they won seven consecutive Grand Slam doubles titles, a feat that has never been matched. He was also an important element of three consecutive winning Davis Cup teams. At the end of 1952, however, Jack Kramer, the promoter and World No. 1 player, induced both Sedgman and McGregor to turn professional. "I hated to leave Davis Cup," said McGregor later, "but the money was too good to turn down. We were getting 25 shillings a day as amateurs, and I had a guarantee of abut $60,000 for three years."[2]

McGregor's career as a professional was less successful than as a amateur. In the 1952–1953 tour against Pancho Segura, which served as the warm-up event to the Kramer-Sedgman headline match, McGregor was beaten by the little Ecuadorian-American 71 matches to 25, losing the first 12 matches. The following year, 1953–1954, in an Australian tour with Segura, Sedgman, and Pancho Gonzales, he was beaten by Gonzales 15 matches to 0.[3] Gonzales was just on the threshold of becoming the greatest player in the world for the rest of the decade.

As a youth, McGregor was a fine all-round athlete, excelling in cricket, Australian-rules football, and tennis. Harry Hopkins, the face of the Australian Davis Cup team for many years, induced him to devote himself exclusively to tennis, and as an amateur he was near the very top of game. Besides winning the Australian championship, he lost the 1951 Wimbledon finals to Dick Savitt and played on three winning Davis Cup teams. By beating the favored Sedgman in the 1952 Australian tournament, he deprived Sedgman of the opportunity to win the coveted Grand Slam of tennis—Sedgman subsequently went on that year to win the three final events. In 1952 he and Sedgman were heavily favored to win their eighth Grand Slam doubles tournament in a row but were shocked in the finals of the United States Open by the pick-up team of the Australian Mervyn Rose and the American Vic Seixas, two men who had never before played together.

In the unofficial but authoritative annual ratings of the world's best amateur players by first John Olliff and then Lance Tingay of the London Daily Telegraph, McGregor was ranked no. 8 in 1950, no. 7 in 1951, and no. 3 in 1952.[4]

At 6'3", McGregor had a powerful serve and overhead but an unreliable forehand[5]. Ellsworth Vines, the great American player of the 1930s, wrote of him: "He was the same height as Pancho Gonzales, faster, moved as well and could jump higher, and once he got to the net he was difficult to pass because of his prehensile reach. The handsome Aussie had the most extraordinary overhead of all time."[6] Kramer, however, who had many opportunities to watch it, did not rate McGregor's overhead as highly as Vines; he wrote in his autobiography that Ted Schroeder had the best overhead of all time, "ahead of Vines, Rosewall, and Newcombe."[7] In his 1979 autobiography, Kramer wrote that "McGregor was one of the weakest players but one of the nicest guys who ever played for me in the pros. As nearly as I could tell, all he wanted to do was save up some money, go back Down Under and play Australian-rules football, which in fact, he played better than he did tennis. And that's what he did."[8]

Returning to Australia from his days as a touring tennis pro, McGregor tried to have himself reinstated as an amateur tennis player but was refused. He then opened a sporting goods store and played parts of five seasons with the West Adelaide football team in the main section of the South Australian competition. Playing in 52 games, he was a member of their Grand Final matches in 1954, 1956, and 1958.

McGregor was inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame in Newport, Rhode Island, in 1999.

Grand Slam record

- Australian Championship

- Singles champion: 1952 (beat Frank Sedgman)

- Singles runner-up: 1950 (to Frank Sedgman), 1951 (to Dick Savitt)

- Men's Doubles champion: 1951 (with Frank Sedgman), 1952 (with Frank Sedgman)

- Singles champion: 1952 (beat Frank Sedgman)

- French Championship

- Men's Doubles champion: 1951 (with Frank Sedgman), 1952 (with Frank Sedgman)

- Wimbledon

- Singles runner-up: 1951 (to Dick Savitt)

- Men's Doubles champion: 1951 (with Frank Sedgman), 1952 (with Frank Sedgman)

- U.S. Championship

- Men's Doubles champion: 1951 (with Frank Sedgman)

- Men's Doubles runner-up: 1952 (with Frank Sedgman, to Mervyn Rose and Vic Seixas)

- Mixed Doubles champion: 1950 (with Margaret Osborne duPont, beat Doris Hart and Frank Sedgman]]

- Men's Doubles champion: 1951 (with Frank Sedgman)

References

- ↑ "The Greatest Doubles Teams and Players", by George Lott, in the May, 1973, issue of Tennis Magazine, reprinted in The Tennis Book, edited by Michael Bartlett and Bob Gillen, page 337. Lott, himself one of the greatest doubles players of all time, called Sedgman and McGregor the fourth best team he had ever seen. "McGregor had a skillful power game while Sedgman was the quickest man at the net I've ever seen."

- ↑ Total Tennis:The Ultimate Tennis Encyclopedia, by Bud Collins, page 703.

- ↑ The History of Professional Tennis, Joe McCauley, page 64.

- ↑ Total Tennis:The Ultimate Tennis Encyclopedia, by Bud Collins, page 916.

- ↑ The Times of London, obituary, January 2, 2007, at [1]

- ↑ The History of Professional Tennis, Joe McCauley, page 60.

- ↑ The Game, My 40 Years in Tennis, by Jack Kramer with Frank Deford, page 296.

- ↑ The Game, My 40 Years in Tennis, by Jack Kramer with Frank Deford, page 180.