Landing craft, vehicle, personnel: Difference between revisions

Pat Palmer (talk | contribs) (PropDel) |

Pat Palmer (talk | contribs) m (Text replacement - "{{seealso|amphibious warfare}}" to "") |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

{{subpages}} | {{subpages}} | ||

{{main|landing craft}} | {{main|landing craft}} | ||

{| border="1" align="right" cellpadding="2" cellspacing="0" width="300" style="margin: 0 0 1em 0.5em" | {| border="1" align="right" cellpadding="2" cellspacing="0" width="300" style="margin: 0 0 1em 0.5em" | ||

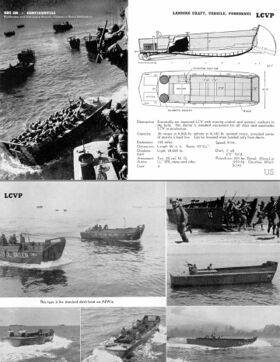

|align="center" colspan="2"|[[Image:LCVP.jpg|300px]] Troops in an LCVP off Omaha Beach<br/> | |align="center" colspan="2"|[[Image:LCVP.jpg|300px]] Troops in an LCVP off Omaha Beach<br/> | ||

Revision as of 12:46, 27 June 2024

| This article may be deleted soon. | ||

|---|---|---|

The Landing craft, vehicle, personnel, commonly known as the LCVP, Peter boat, or Papa boat, was a landing craft widely used by Allied forces in World War II. Also called the Higgins boat, it evolved from a 1936 design by Andrew Higgins. It was used in amphibious warfare to transport troops, light vehicles, equipment, and supplies from the transport ships to the beach. It was these boats that made the D-Day landings at Normandy, Iwo Jima, Guadalcanal, Tarawa, and hundreds of lesser-known places possible. Without Higgins' uniquely designed craft there could not have been a mass landing of troops and material on European shores or on the beaches of the Pacific islands, at least not without a tremendously higher rate of Allied casualties. The salient features of the LCVP were its flat bottom and its bow ramp, which could be lowered to facilitate unloading when the boat grounded on the beach. In an amphibious assault, eight LCVPs in two waves of four usually carried an assault company of a battalion landing team. Later waves of LCVPs brought light vehicles ashore, and still later ones brought supplies. The boats were brought to the assault zone aboard troop transports and attack cargo ships, where they were stored in Welin davits or on deck, usually nested inside the larger LCMs. Troops could board the boats in the davits and be lowered into the water. The boats stored on deck were lowered into the water empty except for their crews; troops boarded them by climbing down cargo nets draped over the sides of the ship. Vehicles and supplies were lowered into the boats already in the water, using cargo booms on the ship. The LCVP could land 36 men with their equipment, or a jeep and 12 men, extract itself quickly, turn around without broaching in the surf, and go back out to get more troops and/or supplies. This was critical—any landing craft that could not extract itself would hinder the ability of succeeding waves to reach the beachhead. The tough, highly maneuverable LCVPs allowed Allied commanders to plan their assaults on relatively less-defended coastline areas and then support a beachhead staging area rather than be forced to capture a port city with wharves and facilities to offload men and material. The 20,000+ LCVPs manufactured by Higgins Industries and others licensed to use Higgins designs landed more Allied troops during the war than all other types of landing craft combined. LCVPs were also adapted to other roles. Some became drone explosive boats; others were modified as shallow-water minesweepers. As expendable items, many LCVPs were disposed of overseas or declared surplus after WWII. During the Korean War the LCVP was called upon to perform a variety of tasks, from amphibious support to mine clearing. The use of LCVPs declined over time, and in its 1989-1990 edition, Jane's Fighting Ships listed only 138 of the craft in the entire United States Navy. References

|

||