Potato

The potato (pl. potatoes), also called Irish potato or white potato or, informally, spud, is one of the world's most important foods. It ranks as the fourth-most-important food crop, after corn (maize), wheat and rice. It provides more calories and more nutrients, more quickly, using less land and in a wider range of climates than any other plant.

It is the root of an herbaceous plant (Solanum tuberosum) that originally evolved in the northern Andean highlands.

The potato was cultivated by various Andean civilizations for at least 2000 years before the Spanish were introduced to it by the Incas in the 16th century. During that time, many different varieties were developed by the Andean peoples, but it was mainly the common white potato that was brought to Europe for cultivation. The potato became a staple crop across northern Europe, but nowhere so much as in Ireland, where an epidemic of potato blight in 1845-46 produced a famine that killed a million or more people and forced as many to emigrate.

The United Nations has declared 2008 the International Year of the Potato.[1] It hopes that greater awareness of the merits of potatoes will contribute to the achievement of its Millennium Development Goals, by helping to alleviate poverty, improve food security and promote economic development.

The great diversity of potatoes developed in the Andes has been expanded even further around the world, so that there are varieties suited to nearly every climate, with harvest times anywhere from midsummer to late fall. Most prefer a well-drained, slightly acid soil, and are planted in the early spring.

Potatoes also come in a wide range of colors, with skin anwhere from brown to purple to red and white, yellow, red, or blue flesh. They are eaten fried, baked, mashed, boiled, or made into flour, and different varieties have been developed for each of these specific purposes.

Peru

Potatoes were first domesticated in Peru more than 7,000 years ago. The country is home to up to 3,500 different varieties of edible tubers, according to the International Potato Center, whose headquarters are near Lima. The United Nations has designated 2008 as the "International Year of the Potato" and not surprisingly Peru hopes to use this to draw attention to itself and its crop. Alan García, the president, has ordered that a government-sponsored program of free breakfasts for poor families should serve bread made from a mixture of potato flour with wheat, which is more expensive and has to be imported. He also wants government food services to start serving chuño, a naturally freeze-dried potato that is traditionally eaten by Andean Indians. Boiled chuño and cheese are said to have replaced sandwiches at cabinet meetings. Peru grows 25 varieties commercially, but exports little. Peruvian yellow potatoes are prized by gourmets for mashing; tubular ollucos are firm and waxy.

Production and consumption

Many countries produce potatoes, primarily for home consumptions. The international market is small.

The ten leaders in production in 2007, in million metric tons:

- 72 China

- 36 Russia

- 26 India

- 19 Ukraine

- 18 USA

- 12 Germany

- 11 Poland

- 8.5 Belarus

- 7.2 Netherlands

- 6.3 France

At first people were highly suspicious, but as economist Adam Smith concluded in 1776:

- "The very general use which is made of potatoes in [Britain] as food for man is a convincing proof that the prejudices of a nation, with regard to diet, however deeply rooted, are by no means unconquerable."

Served as "French fries", often alongside burgers and colas, potatoes are now an icon of globalization.

Belarusians lead the world with 360 kilos per consumed per person per year.

History

Asia

The potato diffused widely after 1700, becoming a major food resource in Europe and East Asia. Following its introduction into China toward the end of the Ming dynasty, the potato immediately became a delicacy of the imperial family. After the middle period of the Qianlong reign (1735-96), population increases and a subsequent need to increase grain yields coupled with greater peasant geographic mobility caused by a slackening of residence registration, led to the rapid spread of potato cultivation throughout China, and was acclimated to local natural conditions.

Boomgaard (2003) looks at the adoption of various root and tuber crops in Indonesia throughout the colonial period and examines the chronology and reasons for progressive adoption of foreign crops - sweet potato, Irish potato, bengkuang (yam beans), and cassava.

Europe

In Britain the potato promoted economic development by underpinning the Industrial Revolution in the 19th century. As a cheap source of calories and nutrients that was easy to cultivate on small backyard plots, it liberated workers from the land. Potatoes became popular in the north of England, where coal was readily available, so a potato-driven population boom provided ample workers for the new factories. Marxist Friedrich Engels even declared that the potato was the equal of iron for its “historically revolutionary role”.

Throughout Europe the most important new food in the 19th century was the potato, which had three major advantages over other foods: its lower rate of spoilage, its bulk (which easily satisfied hunger), and its cheapness. The crop slowly spread across Europe, such that, for example, by 1845 it occupied one-third of Irish arable land. Potatoes comprised about 10% of the caloric intake of Europeans. Other foods imported from the New World included cod, sugar, rice, flour, and rum. These also provided an additional 10% of daily calories and proved a crucial factor in biodiversity of crops, thus preventing famines.[2]

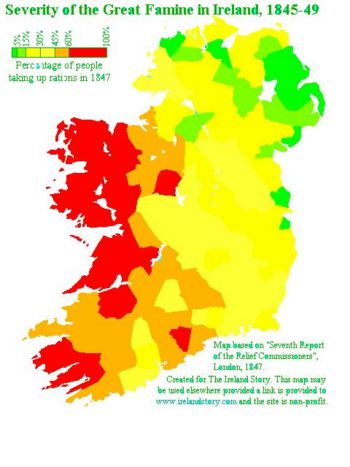

The Lumper potato, widely cultivated in western and southern Ireland before and during the great famine, was tasteless, wet, and poorly resistant to the potato blight, but yielded large crops and usually provided adequate calories for peasants and laborers. Heavy dependence on this potato led tio disaster when the potato blight turned a newly harvested potato into a putrid mush in minutes. The Irish Famine in the British-controlled island of Ireland, 1845-49, was a catastrophic failure in the food supply that led to approximately a million deaths, vast social disruption and to massive emigration.

The Dutch potato-starch industry grew rapidly in the 19th century, especially under the leadership of entrepreneur Willem Albert Scholten (1819-92).

US and Canada

Potatoes were planted in Idaho as early as 1838; by 1900 the state's production exceeded a million bushels. Prior to 1910, the crops were stored in barns or root cellars, but by the 1920s potato cellars came into use. U.S. potato production has increased steadily; two-thirds of the crop comes from Idaho, Washington, Oregon, Colorado, and Maine, and potato growers have strengthened their position in both domestic and foreign markets.

By the 1960s, the Canadian Potato Research Centre in Fredericton, New Brunswick, was one of the top six potato research institutes in the world. Established in 1912 as a dominion experimental station, the station began in the 1930s to concentrate on breeding new varieties of disease-resistant potatoes. In the 1950s-60s the growth of the french fry industry in New Brunswick led to a focus on developing varieties for the industry. By the 1970s the station's potato research was broader than ever before, but the station and its research programs had changed, as emphasis was placed on serving industry rather than potato farmers in general. Scientists at the station even began describing their work using engineering language rather than scientific prose.[3]

Bibliography

- Economist. "Llamas and mash," The Economist Feb 28th 2008 online

- Economist. "The potato: Spud we like," (leader) The Economist Feb 28th 2008 online

- Boomgaard, Peter. "In the Shadow of Rice: Roots and Tubers in Indonesian History, 1500-1950." Agricultural History 2003 77(4): 582-610. Issn: 0002-1482 Fulltext: Ebsco

- McNeill, William H. "How the Potato Changed the World's History." Social Research 1999 66(1): 67-83. Issn: 0037-783x Fulltext: Ebsco, by a leading historian

- McNeill, William H. "The Introduction of the Potato into Ireland," Journal of Modern History 21 (1948): 218-21. in JSTOR

- Ó Gráda, Cormac. Black '47 and Beyond: The Great Irish Famine in History, Economy, and Memory. (1999). 272 pp.

- Ó Gráda, Cormac, Richard Paping, and Eric Vanhaute, eds. When the Potato Failed: Causes and Effects of the Last European Subsistence Crisis, 1845-1850. (2007). 342 pp. ISBN: 978-2-503-51985-2. 15 essays by scholars looking at Ireland and all of Europe

- Reader, John. Propitious Esculent: The Potato in World History (2008), 315pp the standard scholarly history

- Salaman, Redcliffe. The History and Social Influence of the Potato (1949)

- Zuckerman, Larry. The Potato: How the Humble Spud Rescued the Western World. (1998). 304 pp.

Primary Sources

See also

Online resources

notes

- ↑ See International Year of the Potato website

- ↑ John Komlos, "The New World's Contribution to Food Consumption During the Industrial Revolution." Journal of European Economic History 1998 27(1): 67-82. Issn: 0391-5115

- ↑ Steven Turner, and Heather Molyneaux, "Agricultural Science, Potato Breeding and the Fredericton Experimental Station, 1912-66." Acadiensis 2004 33(2): 44-67. Issn: 0044-5851