Angular momentum (quantum)

In quantum mechanics, angular momentum is a vector operator of which the three components have well-defined commutation relations. This operator is the quantum analogue of the classical angular momentum vector.

Angular momentum entered quantum mechanics in one of the very first—and most important—papers on the "new" quantum mechanics, the Dreimännerarbeit (three men's work) of Born, Heisenberg and Jordan (1926).[1] In this paper the orbital angular momentum and its eigenstates are already fully covered by the algebraic techniques of commutation relations and step up/down operators that will be treated in the present article. In 1927, Wolfgang Pauli introduced spin angular momentum,[2] which is a form of angular momentum without a classical counterpart.

Angular momentum theory—together with its connection to group theory— brought order to a bewildering number of spectroscopic observations in atomic spectroscopy, see, for instance, Wigner's seminal work.[3] When in 1926 electron spin was discovered and Pauli proved less than a year later that spin was a form of angular momentum, its importance rose even further. To date the theory of angular momentum is of great importance in quantum mechanics. It is an indispensable discipline for the working physicist, irrespective of his field of specialization, be it solid state physics, molecular-, atomic,- nuclear,- or even hadronic-structure physics.[4]

Qualitative description

In classical mechanics the angular momentum of a body is a vector that can have any length and any direction. Think of a spinning bicycle wheel. The length of its angular momentum is proportional to the number of revolutions per unit time and the direction is along the axle. As is well-known the angular velocity of the wheel and the direction of the axle are both continuously changeable. In quantum theory this is different.

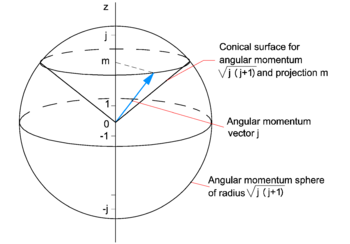

Consider a quantum system with well-defined angular momentum j, for instance an electron orbiting a nucleus. In the first place the length of the angular momentum is quantized, it can only take the values

and no other values. Hence the endpoint of the angular momentum j (the blue arrow in the figure) lies on the surface of a sphere of radius . In the second place, its projection on an axis in space (the quantization axis, usually taken as the z-axis) is quantized, it can only take the values

where j is the quantum number that determines the length of j. The endpoint of the blue arrow does not cover the full surface of the sphere, but can only lie on a circle intersecting the sphere and a cone, because the projection of j on the z-axis is the discrete value m. The latter quantum number is integral or half-integral, depending on whether j is integral or half-integral.

The position of the blue arrow within the surface of the cone is completely undetermined, it is equally probable everywhere. This is an illustration of Heisenberg's uncertainty principle.

Orbital angular momentum

The classical angular momentum of a point mass is,

where r is the position and p the (linear) momentum of the point mass. The simplest and oldest example of an angular momentum operator is obtained by applying the quantization rule:

where is Planck's constant (divided by 2π) and ∇ is the gradient operator. This rule applied to the classical angular momentum vector gives a vector operator with the following three components,

The following commutation relations can be proved,

- Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle [L_x,\,L_y] = i \hbar L_z, \quad [L_z,\,L_x] = i \hbar L_y, \quad [L_y,\,L_z] = i \hbar L_x. }

The square brackets indicate the commutator of two operators, defined for two arbitrary operators A and B as

For instance,

where we used that all the terms of the kind

mutually cancel. Since the three components of L do not commute, they do not have a common set of eigenfunctions.

The total angular momentum squared is defined by

This operator commutes with any of the three components,

so that common eigenfunctions of L2 and one of its components can be found.

Note, parenthetically, that eigenfunctions of L2 have been known since the nineteenth century, long before quantum mechanics was born. They are spherical harmonic functions. Indeed, in terms of spherical polar coordinates the operator is,

and this expression appears in the associated Legendre equation.

Spin angular momentum

Pauli introduced in 1927 the following three matrices, which are now known as Pauli spin matrices,

These Hermitian matrices represent Hermitian operators on a two-dimensional linear space over the field of complex numbers: spin space. Spin angular momentum operators are defined by

The commutation relations of these operators follow by matrix multiplication, for instance,

It is shown in this manner that

which may be compared with the commutation relations of the orbital angular momenta given earlier.

Abstract angular momentum operators

We have seen two examples of angular momentum operators, but many more can be given. For instance, the sum operator s + L, or sum operators of more than one particle are also angular momentum operators. The essential characteristic that all these operator share is that they have three components with well-defined commutation relations. Taking a somewhat more abstract point of view, one comes to the following definition: An angular momentum operator is a vector operator with three Hermitian component operators jx, jy, and jz, that satisfy the commutation relations

where is the Levi-Civita symbol,

Together the three components define the vector operator j. The square of the length of j is defined as

We also define raising j+ and lowering j− operators (also known as step up/down operators),

Angular momentum states

From here on we put .

It can be shown from the above definitions that j2 commutes with jx, jy, and jz

When two Hermitian operators commute a common set of eigenfunctions exists. Conventionally jz is chosen to supplement j2. From the commutation relations the possible eigenvalues can be found. The result is

The raising and lowering operators change the value of

with

A (complex) phase factor could be included in the definition of The choice made here is in agreement with the Condon and Shortley phase conventions. The angular momentum states must be orthogonal (because their eigenvalues with respect to a Hermitian operator are distinct) and they are assumed to be normalized

Proof of properties of eigenstates

The angular momentum operators satisfy

From these properties alone the eigenstates can be constructed. The steps in the construction are:

- Since j2 and jz commute, we can find a common eigenvector with

- .

- Since a Hermitian operator squared has only real, nonnegative, expectation values, , and since an eigenvalue is a special kind of expectation value—namely one with respect to an eigenvector—it follows that j2 has only non-negative real eigenvalues. Therefore we write its eigenvalue as the squared number a2.

- In view of the commutation relations and , we find that

- and

- Hence the step up operator yields an eigenvector of j2 with the same eigenvalue and an eigenvector of jz with eigenvalue b + 1, so that

- If we apply j+ now k + 1 times we obtain, using , the ket with norm

- The left hand side is nonnegative, while k is unlimited. Thus, if we let k increase, there comes a point that the norm on the left hand side would have to be negative or zero, while the norm on the right hand side would still be positive. A negative norm is in contradiction with the fact that the ket belongs to a Hilbert space. Since no power of the step up operator maps a ket outside Hilbert space, there must exist a maximum value kmax of the integer k, such that the ket , while exactly . For that value of k it follows that a2 = (b + kmax)(b + kmax + 1).

- Similarly l + 1 times application of j− gives a zero ket with and a2 = (b − lmax)(b − lmax − 1).

- From the fact that a2 = (b + kmax)(b + kmax + 1) = ( b − lmax)( b − lmax − 1) follows by solving the equation: 2b = lmax − kmax, so that b is integral or half-integral. The quantum number b + k is traditionally designated by m. Also m is either integral or half-integal. The maximum value of m for which the ket will be designated by j = b + kmax. The number j is integral when m is integral and half-integral when m is half integral. Note that a2 = j (j + 1).

- Change now the notation, and assume that the normalization factor N is chosen such that |j, m> is normalized to unity,

- The requirement that all kets involved are normalized, while fixing phases, gives the formula to be proved. The normalization is simple:

References

- ↑ M. Born, W. Heisenberg, and P. Jordan, Zur Quantenmachanik II, Zeitschrift f. Physik. vol. 35, pp. 557-615 (1926)

- ↑ W. Pauli jr., Zur Quantenmechanik des magnetischen Elektrons, Zeitschrift f. Physik. vol. 43, pp. 601-623 (1927)

- ↑ E. P. Wigner, Gruppentheorie und ihre Anwendungen auf die Quantenmechanik der Atomspektren, Vieweg Verlag, Braunschweig (1931). Translated into English: J. J. Griffin, Group Theory and its Application to the Quantum Mechanics of Atomic Spectra Academic Press, New York (1959).

- ↑ L. C. Biedenharn, J. D. Louck, Angular Momentum in Quantum Physics, Addison-Wesley, Reading, Massachusetts (1981)

![{\displaystyle [A,\,B]\equiv AB-BA.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/56ca4d00fb784d1086d7fb1667ad4814791e350c)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}{\big [}L_{x},\,L_{y}{\big ]}=&-\hbar ^{2}\left[{\Big (}y{\frac {\partial }{\partial z}}-z{\frac {\partial }{\partial y}}{\Big )}{\Big (}z{\frac {\partial }{\partial x}}-x{\frac {\partial }{\partial z}}{\Big )}-{\Big (}z{\frac {\partial }{\partial x}}-x{\frac {\partial }{\partial z}}{\Big )}{\Big (}y{\frac {\partial }{\partial z}}-z{\frac {\partial }{\partial y}}{\Big )}\right]\\=&-\hbar ^{2}\left[y{\frac {\partial }{\partial x}}-x{\frac {\partial }{\partial y}}\right]=i\hbar \left[-i\hbar {\Big (}x{\frac {\partial }{\partial y}}-y{\frac {\partial }{\partial x}}{\Big )}\right]=i\hbar L_{z},\\\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0c58b8e28ba330c9552c5a9cb192fa675275d0c1)

![{\displaystyle [\mathbf {L} ^{2},\,L_{k}]=0\quad {\hbox{for}}\quad k=x,y,z,}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/8f096a6f3bcf8c69c0e972663ea4a3c7b2910058)

![{\displaystyle L^{2}=-\hbar ^{2}\left[{\frac {1}{\sin \theta }}{\frac {\partial }{\partial \theta }}\sin \theta {\frac {\partial }{\partial \theta }}+{\frac {1}{\sin ^{2}\theta }}{\frac {\partial ^{2}}{\partial \varphi ^{2}}}\right],}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/8150cd1e0af30950ba0a58515a9a1b9af3f77c78)

![{\displaystyle [s_{x},\,s_{y}]\leftrightarrow {\frac {\hbar ^{2}}{4}}[{\boldsymbol {\sigma }}_{x}{\boldsymbol {\sigma }}_{y}-{\boldsymbol {\sigma }}_{y}{\boldsymbol {\sigma }}_{x}]={\frac {i\hbar ^{2}}{2}}{\begin{pmatrix}1&0\\0&-1\\\end{pmatrix}}\leftrightarrow i\hbar s_{z}.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/36c5767ed9c81063e34e62dbe9b2900abc838542)

![{\displaystyle [s_{x},\,s_{y}]=i\hbar s_{z},\quad [s_{z},\,s_{x}]=i\hbar s_{y},\quad [s_{y},\,s_{z}]=i\hbar s_{x},}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f0a0edf6818a2ad76c004bb44b8a305967960590)

![{\displaystyle [j_{k},j_{l}]=i\hbar \sum _{m=x,y,z}\varepsilon _{klm}j_{m},\quad k,l,m=x,y,z,}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4f44a914d2674a1f8913410e9f40ca9ba479f3f0)

![{\displaystyle [\mathbf {j} ^{2},\,j_{k}]=0\quad \mathrm {for} \;\;k=x,y,z.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/63f65d2a1606ab7b3eee59266da05b756f07bdc9)

![{\displaystyle [\mathbf {j} ^{2},\,j_{\pm }]=[\mathbf {j} ^{2},\,j_{z}]=0,\qquad [j_{z},\,j_{\pm }]=\pm j_{\pm },\qquad j_{-}j_{+}=\mathbf {j} ^{2}-j_{z}(j_{z}+1).}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4b67577669b58488ea9ffd418719a43bd4c21043)

![{\displaystyle \scriptstyle [j^{2},j_{\pm }]=0}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/011013f637b3615fab9a34b01c6b7d8ea64fd7f8)

![{\displaystyle \scriptstyle [j_{z},j_{\pm }]=\pm j_{\pm }}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/14c67cafe08ef07a4842272ed369d52d30a63f99)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\langle a+b+k+1|a+b+k+1\rangle &=\langle a,b+k|j_{-}j_{+}|a,b+k\rangle =\langle a,b+k|\mathbf {j} ^{2}-j_{z}(j_{z}+1)|a,b+k\rangle \\&=[a^{2}-(b+k)(b+k+1)]\langle a,b+k|a,b+k\rangle .\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/1ee598bfb75ad0e391adb4e8fe204f3836fb3d6d)