National Security Agency

The National Security Agency (NSA), formally the National Security Agency/Central Security Service is part of the United States Department of Defense and also the United States intelligence community. Its headquarters are at Fort Meade, Maryland, although it has worldwide installations.

The headquarters, which consists of several large buidings, an impressive fence, and acres of parking lots, is reputed to have the most computers of any place on earth.

The agency has dual responsibilities:

- As a member of the United States intelligence community, it has the principal responsibility for collecting and processing signals intelligence.

- As the agency responsible for the "Information Assurance mission [to provide] the solutions, products, and services, and [conduct] defensive information operations, to achieve information assurance for information infrastructures critical to U.S. national security interests"[1]

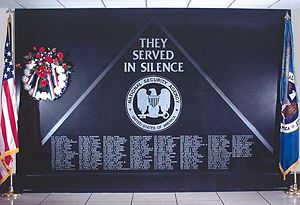

Immediately outside one of the security gates is the National Cryptologic Museum and the National Vigilance Park, the latter holding three aircraft, one from each service, and of a type that was lost during SIGINT operations.

SIGINT personnel not only died on duty in aircraft. The first U.S. soldier killed in Vietnam belonged to an Army SIGINT unit. A large number of personnel were killed in the Israeli attack on the SIGINT ship, USS Liberty.

Executive organization

The Director, National Security Agency(DIRNSA)/Chief, Central Security Service is an active-duty, three-star officer from one of the military services. The Deputy Director, National Security Agency is a career civilian. Two senior officials are the #the Signals Intelligence Director (SID) and the Information Assurance Director (IAD). There are usually some very senior staff specialists bearing titles such as Chief Cryptologist.

As mentioned, NSA is part of the United States intelligence community. There is usually a government-wide communications security committee just below the National Security Council level. NSA also is the lead agency for Operations Security (OPSEC), a counterintelligence function within government that goes beyond communications security/

NSA and its predecessors have had a very close relationship with its British Counterpart, the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ). The resident U.S. representative there, the Senior U.S. Liaison Officer (SUSLO) holds what is considered a key position.

While the exact organizaation is classified, and has varied over time, it will generally contain functions including:

- National level SIGINT-collection management and operations

- Coordination of tactical SIGINT

- Advanced research and development. NSA is reputed to be the world's largest employer of mathematicians.

- SIGINT processing organizations, generally organized on a regional basis depending on national priorities. NSA is not considered to be an analytic agency that produces "finished intelligence", although, by all indications, it will report on the patterns of COMINT and ELINT information, rather than the content, for example, of messages read through COMINT.

- Defensive information operations, including creating, either in-house or on contract, U.S. COMSEC equipment for classified communications, and cryptographic keying material for classified and certain other types of sensitive but unclassified government communications.

Post WWII U.S. SIGINT organization and the formation of NSA

- See also: SIGINT in the Second World War

During the Second World War, the Army and Navy had separate signals intelligence and communications security organization, which coordinated only informally. Depending on the service, tactical SIGINT, cryptologic development, strategic SIGINT, and cryptologic operations might be performed by autonomous organizations within a service department.

After the end of World War II, all the Western allies began a rapid drawdown. At the end of WWII, the US still had a COMINT organization split between the Army and Navy. [2] A 1946 plan listed Russia, China, and a [redacted] country as high-priority targets. This would have long-term implications for Korea and Vietnam.

The Army and Navy formed a "Joint Operating Plan" to cover 1946-1949, but this had its disadvantages. The situation became a good deal more complex with the passage of the National Security Act of 1947, which created a separate Air Force and Central Intelligence Agency, as well as unifying the military services under a Secretary of Defense. While the CIA remained primarily a consumer, the Air Force wanted its own SIGINT organization, responsive to its tactical and strategic needs, just as the Army and Navy often placed their needs beyond that of national intelligence.[3] The Army Security Agency (ASA) had shared the national COMINT mission with the Navy's Communications Supplementary Activity (COMMSUPACT) - which became the Naval Security Group in June 1950. During and after World War II, a portion of Army COMINT assets was dedicated to support of the U.S. Army Air Corps, and, when the independent Air Force was created in 1947, these cryptologic assets were resubordinated to the new organization as the Air Force Security Service (AFSS).

U.S. Secretary of Defense James Forrestal rejected the early service COMINT unification plans. The Department of State objected to the next draft, which put the Central Intelligence Group/Central Intelligence Agency in charge of national COMINT. As a compromise and to centralize common services, the Armed Forces Security Agency (AFSA), was formed by secret executive order in 1948. As opposed to NSA, AFSA did not have the authority for central control of individual service COMINT and COMSEC. Policy direction of COMINT came from the U.S. Communications Intelligence Board (USCIB) which, in April 1949, requested $22 million in funds, including 1,410 additional civilian employees, to expand the COMINT effort.

Pacific COMINT targeting prior to the Korean War

For the Pacific, the USCIB targeted China, and Russia in both the European and Pacific theaters, but Korea was a low-priority target: On its second-tier priority list were items of "high importance"; for the month prior to the war, Japan and Korea were item number 15 on the second list, but this did not focus on Korea itself. The specific requirements were "Soviet activities in North Korea", "North Korean-Chinese Communist Relations", and "North Korean-South Korean relations, including activities of armed units in border areas." [4] Korean coverage was incidental to Soviet and Chinese interests in the Korean Peninsula.[4] Both the surprise attack, and the difficulty of rapidly enlarging the SIGINT organization, showed that the organization was imperfect.

Was there early warning of the Korean War? Perhaps, but hindsight is a wonderful thing. As with the retrospective analysis of COMINT immediately after Pearl Harbor, certain traffic, if not a smoking gun, would have been suggestive, to an astute analyst trusted by the high command. Before the invasion, targeting was against Chinese and Soviet targets with incidental mention of Korea. Prior to 1950 there were two COMINT hints of more than usual interest in the Korean peninsula by communist bloc nations, but neither was sufficient to provide specific warning of a June invasion.

Early warning and the Korean War

In April 1950, ASA undertook a limited "search and development" study of DPRK traffic. Two positions the second case, as revealed in COMINT, large shipments of bandages and medicines went from the USSR to North Korea and Manchuria, starting in February 1950. These two actions made sense only in hindsight, after the invasion of South Korea occurred in June 1950.

Some North Korean communications were intercepted between May 1949 and April 1950 because the operators were using Soviet communications procedures. Coverage was dropped once analysts confirmed the non-Soviet origin of the material.

Within a month of the North Korean invasion, the JCS approved the transfer of 244 officers and 464 enlisted men to AFSA and recommended a large increase in civilian positions. In August, the DoD comptroller authorized an increase of 1,253 additional civilian COMINT positions. Given the administration's belief that the conflict in Korea could be part of a wider war, only sine of the increase would go to direct support of the conflict in Korea.

COMINT, supported by information from other open and secret sources, showed a number of other military-related activities, such as VIP visits and communications changes, in the Soviet Far East and in the PRC, but none was suspicious in itself. Even when consolidated by AFSA in early 1951, these activities as a whole did not provide clear evidence that a significant event was imminent, much less a North Korean invasion of the South.

In 1952, when personnel levels and a more static war allowed some retrospective analysis, AFSA reviewed unprocessed intercept from the June 1950 period. Analysts could not find any message which would have given advance warning of the North Korean invasion. One of the earliest, if not the earliest, messages relating to the war, dated June 27 but not translated until October, referred to division level movement by North Korean forces. [4]

NSA created, but the services roll on

President Harry Truman, on 24 October 1952, issued a directive that set the stage for the National Security Agency, whose scope went beyond the pure military. NSA was created on 4 November 1952.[3]

The Service Cryptologic Agencies still had their own identity, even after the formation of NSA. They continued reorganizations independently of NSA; in 1955, ASA took over electronic intelligence (ELINT) and electronic warfare functions previously carried out by the Signal Corps. Since its mission was no longer exclusively identified with intelligence and security, ASA was withdrawn from G-2 control and resubordinated to the Army Chief of Staff as a field operating agency.

Eventually, the individual service SIGINT organizations were to become Service Cryptologic Elements (SCE), with dual reporting to their local operational commands and to NSA/CSS -- and sometimes very little to the local command. The captain of the USS Pueblo, a SIGINT ship, was discouraged from entering the SIGINT compartments of the ship. Pilots of SIGINT aircraft were told where to fly, but were not informed, in detail, what the technicians on board were doing -- unless the technicians issued an urgent warning of a hostile aircraft coming close. Several U.S. SIGINT aircraft were damaged or destroyed.

While the names were to continue to change, the main SCEs reorganized into units principally serving NSA's national-level goals, although there were also tactical SIGINT units within a dual chain of command. Since most NSA system was under compartmented control systems, local military commanders might not have the appropriate clearance. The phrase "behind the green door", from a song and a pornographic movie, became the euphemism for the [[Sensitive compartment information facility}sensitive compartment information facilities (SCIF), behind whose locked and guarded doors the actual SIGINT was done.

| Service | SCE |

|---|---|

| Army | Army Security Agency |

| Navy | Naval Security Group (Marine Radio Battalions were primarily tactical) |

| Air Force | Air Force Security Service |

1950-1954: Strategic SIGINT targeting of the USSR and monitoring Indocina

In the fifties, only aircraft platforms could obtain SIGINT over the USSR. A Soviet source pointed out that aircraft were of limited usefulness, due to being vulnerable to fighters and antiaircraft weapons. (Translator's estimate: in the period 1950-1969, about 15 US and NATO reconnaissance aircraft were shot down over the USSR, China, the GDR and Cuba). The US, therefore, undertook the WS-117L reconnaissance satellite project, approved by President Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1954, within which was a signal intercept subsystem under Project PIONEER FERRET. [5]

The Viet Minh, at first, used captured French communications equipment. Under the French, no Vietnamese had been trained in cryptography, so, the initial messages were sent in the clear. On September 23, 1945, the US intercepted a message from Ho Chi Minh to Joseph Stalin, requesting aid for flood victims. This traffic immediately triggered more suspicion of Ho's relationship to Moscow, but it turned out to be one in a series of messages to world leaders. [2]

On September 12, the Viet Minh established a Military Cryptographic Section, and, with their only reference a single copy of French Capitaine Baudoin's Elements Cryptographic, and began to develop their own cryptosystems. Not surprisingly, these were very basic. By early 1946, they had established a network of radio systems, still transmitting with only minimal communications security.

The French had a number of direction-finding stations, with about 40 technicians. By 1946, the French had identified a number of Viet Minh network and were able to do traffic analysis. They also monitored Nationalist and Communist Chinese, British, Dutch and Indonesian communications[2] In general, however, SIGINT in French Indochina was limited by the availability of linguists. [6]

While the US began to provide military supplies to the French, approximately at the time of the start of operations of the Armed Forces Security Agency in 1949, Indochina was a low COMINT priority. Even in 1950, the position of the French there was considered "precarious", both in a Joint Chiefs of Staff assessment and a National Intelligence Estimate.

"After abolition of the French Indochina opium monopoly in 1950, SDECE imposed centralized, covert controls over the illicit drug traffic that linked the Hmong poppy fields of Laos with the opium dens operating in Saigon." This generated profits that funded French covert operations in French Indochina". [6]

In the spring and fall of 1951, [2], French forces beat back Viet Minh attacks, but continued to be increasingly hard-pressed in 1953. While the NSA history is heavily redacted, it appears that the French may have provided COMINT to the CIA.

In 1953, the French began their strongpoint at Dien Bien Phu, for reasons the NSA history said were unclear. Factors may have included controlling some restive tribal groups, or, having seen the effect of US firepower in Korea, hoped to draw the Viet Minh into a similar "killing zone". The history mentioned the possibility that the French intelligence service did not want to lose a profitable opium operation in the area, but suggested it was more likely that the Viet Minh were making a profit in this area.

Again concealed by heavy redactions in the NSA history, it appeared that the French had intelligence of multiple Viet Minh units in the Dien Bien Phu area, but no good idea of their size. The overall commander, Henri Navarre, rejected the possibility that these units could be of division size, and that the Viet Minh was capable of a multidivisional operation against Dien Bien Phu.

The NSA history indicates, although the sources and methods are redacted, that the US had very good data on both sides at Dien Bien Phu. As the position crumbled, the French apparently thought that they could get combat assistance from the US. Only the heading of that an NSA emergency force was being considered survived redaction. Nevertheless, while some of the Joint Chiefs did recommend a US relief expedition, President Dwight Eisenhower, as well as Gen. Matthew Ridgway, having just come from the Korean command, rejected the idea of another land war in Asia.

Setting the stage for Southeast Asian operations (1954-1960)

There are several ways to split US SIGINT regarding Southeast Asia into periods. In this article, the emphasis is on strategic systems; see SIGINT from 1945 to 1989 for both tactical details and more information on strategic operations. Gilbert's four periods are focused on the deployment of American units.[7] In contrast, Hanyok's periods [8], although the redactions make it difficult to see exactly why he created chapters as he did, but it would appear that he ties them more to VC/NVA activities, as well as RVN politics, than the US view.

Although SIGINT personnel were present in 1960, Gilbert breaks the ASA involvement in Vietnam into four chronological phases, Although SIGINT personnel were present in 1960, Gilbert breaks the ASA involvement in Vietnam into four chronological phases,[7] which do not match the more recent NSA history by Hanyok, which is less focused on events with the US military. [9]

- Pre-buildup, 1954-1960.

- The Early Years: 1961-1964, characterized by direction-finding and COMSEC, ending with the Gulf of Tonkin Incident. This partially overlaps the period of "SIGINT and the Attempted Coups against Diem, 1960-1962"[9]

- The Buildup: 1965-1967, with cooperation at the Corps/Field Force level, and the integration of South Vietnamese linguists. Major ASA units at this time were the 509th Radio Research Group and 403d RR (Radio Research) SOS (Special Operations Detachment)[7]

- Electronic Warfare: 1968-1970, with substantial technical experimentation

- Vietnamization: 1971-1973, as the mission shifted back to training, advising, and supporting South Vietnamese units. which do not match the more recent NSA history by Hanyok, which is less focused on events with the US military. [9]

- The Early Years: 1961-1964, characterized by direction-finding and COMSEC, ending with the Gulf of Tonkin Incident. This partially overlaps the period of "SIGINT and the Attempted Coups against Diem, 1960-1962"[9]

- The Buildup: 1965-1967, with cooperation at the Corps/Field Force level, and the integration of South Vietnamese linguists. Major ASA units at this time were the 509th Radio Research Group and 403d RR (Radio Research) SOS (Special Operations Detachment)[7]

- Electronic Warfare: 1968-1970, with substantial technical experimentation

- Vietnamization: 1971-1973, as the mission shifted back to training, advising, and supporting South Vietnamese units.

Hanyok divides the history into periods based on enemy action, while Gilbert divides it on American deployments and changes in technology.[8]US SIGINT support during the Vietnam War came principally from service cryptographic units, with some NSA coordination. Units still belonged to their parent service, such as the Army Security Agency and Naval Security Group. Some SIGINT personnel were assigned to covert special operations and intelligence units.Although SIGINT personnel were present in 1960, Gilbert breaks the ASA involvement in Vietnam into four chronological phases,[7] which do not match the more recent NSA history by Hanyok, which is less focused on events with the US military. [9]

- The Early Years: 1961-1964, characterized by direction-finding and COMSEC, ending with the Gulf of Tonkin Incident. This partially overlaps the period of "SIGINT and the Attempted Coups against Diem, 1960-1962"[9]

- The Buildup: 1965-1967, with cooperation at the Corps/Field Force level, and the integration of South Vietnamese linguists. Major ASA units at this time were the 509th Radio Research Group and 403d RR (Radio Research) SOS (Special Operations Detachment)[7]

- Electronic Warfare: 1968-1970, with substantial technical experimentation

- Vietnamization: 1971-1973, as the mission shifted back to training, advising, and supporting South Vietnamese units.[7]

The NSA History redacted most information, not already public, from 1954 to 1960, but gaps can be filled from other sources A section is titled "Diem's War against Internal Dissent". It opens with an observation that most opposition to President Diem was inflamed by "his program of wholesale political suppression, not just of the Viet Minh cadre that had stayed in the south after Geneva, but against all opposition, whether it was communist or not." By mid-1955, according to Diem, approximately 100,000 Communists were alleged to have surrendered, or rallied to Diem, although the NSA author suggests this did not correspond to political reality, since there were only an estimated 10,000 "stay-behinds". It was clear, however, that the number of communists at large dropped dramatically.

The history mentions that Diem's security organs were given a free hand by Ordnance Number 6 of January 1956, putting anyone deemed a threat to the defense of the state and public safety," at least in house arrest. A quote from Life magazine, generally considered friendly to Diem, suggested that a substantial number of non-communists had been arrested. This is followed by a brief note, "Yet in that same process of neutralizing opposition, Diem set the seeds for his own downfall." This followed by long redactions. Both Diem and the US Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG), according to the NSA history, felt the communists were going into "last gasps" in late 1959.[9]

SIGINT in Southeast Asia, 1954-1960

The history mentions that Diem's security organs were given a free hand by Ordnance Number 6 of January 1956, putting anyone deemed a threat to the defense of the state and public safety," at least in house arrest. A quote from Life magazine, generally considered friendly to Diem, suggested that a substantial number of non-communists had been arrested. This is followed by a brief note, "Yet in that same process of neutralizing opposition, Diem set the seeds for his own downfall." This followed by long redactions. Both Diem and the US Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG), according to the NSA history, felt the communists were going into "last gasps" in late 1959.[9]

US SIGINT support during the Vietnam War came principally from service cryptographic units, with some NSA coordination. Units still belonged to their parent service, such as the Army Security Agency and Naval Security Group. Some SIGINT personnel were assigned to covert special operations and intelligence units.[7] There are several ways to split US SIGINT regarding Southeast Asia into periods. Gilbert's four periods are focused on the deployment of American units. In contrast, Hanyok's periods, although the redactions make it difficult to see exactly why he created chapters as he did, but it would appear that he ties them more to VC/NVA activities, as well as RVN politics, than the US view.

1960 Events in SES and organizing the SIGINT history

US SIGINT support during the Vietnam War came principally from service cryptographic units, with some NSA coordination. Units still belonged to their parent service, such as the Army Security Agency and Naval Security Group. Some SIGINT personnel were assigned to covert special operations and intelligence units.[7] There are several ways to split US SIGINT regarding Southeast Asia into periods. Gilbert's four periods are focused on the deployment of American units. In contrast, Hanyok's periods, although the redactions make it difficult to see exactly why he created chapters as he did, but it would appear that he ties them more to VC/NVA activities, as well as RVN politics, than the US view. 1960, however, opened with a "disaster for the South Vietnamese" in Tay Ninh province, followed by a number of battles lost.[9] To SIGINT analysts at NSA, the increase in communications activity in 1960 indicated a strong growth of the communists.

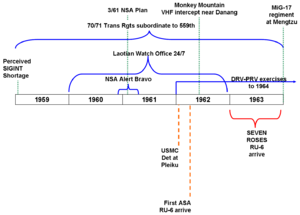

In December 1960, while much text was redacted, the NSA history indicates there was major concern, about a Soviet airlift of supplies, and a "real concern that either the Soviets or the Chinese Communists, or both, would go beyond the supply flights and directly intervene in the fighting. On 14 December 1960, the NSA director, VADM Laurence L. Frost, institute a SIGINT Readiness Condition BRAVO on a theaterwide level throughout the Far East." The nature of BRAVO was not given, and the theater went back to ALPHA, apparently the lowest, by February 1961, when the intelligence community (IC) decided there was no chance the Soviets or PRC would join the fighting.[8]

By the end of the year, NSA estimated that the number of stations had quadrupled, with the communications activity in the Saigon area growing sixfold or sevenfold. The increased communications activity, according to the history, was so striking that Allen W. Dulles, the Director of Central Intelligence and head of the intelligence community, personally went to President John F. Kennedy, in January 1961, to brief him on the increase.

A section entitled "SIGINT and the Attempted Coups against Diem, 1960-1962", opens, on 11 November 1961, with the sounds of a coup attempt in Saigon. "Diem's luck held. The coup leaders were disorganized and amateurish. Rather than seize the palace [where Diem and his brother were barricaded], they preferred to talk. They also failed to capture the radio stations and other communications centers and failed to set up roadblocks..." and other obstacles to loyalist troops, who caused the coup members to flee, often to Cambodia. "American SIGINT had been surprised by the coup, as had American intelligence in general. In the coup's aftermath, SIGINT discovered, through decrypted VC regional headquarters messages, that the communists were taking an active interest in the failed coup, learning valuable lessons from its shortcomings, which would translate into plans to take advantage of any future maneuvers against Diem.[9]

Intercepts also made it clear that the attempted coup by paratroopers had surprised the Communists as much as Diem. "In the mad scramble for positioning that followed, the Viet Cong in the Nam Bo [Saigon] region directed subordinate elements to help soldiers, officers and others (politicians and security personnel) involved in the coup to escape."[9] This was followed by long redactions, and then the question, "Were the Communists on to something? There is no doubt that they were correct in their assessment that the Americans were disillusioned with Diem's failure to select a course of social reform and stick with it." They believed the Americans were contacting dissidents and planning new coups, but NSA states there was no evidence of American involvement; the South Vietnamese were more than capable of planning their own. 1960, however, opened with a "disaster for the South Vietnamese" in Tay Ninh province, followed by a number of battles lost.[9] To SIGINT analysts at NSA, the increase in communications activity in 1960 indicated a strong growth of the communists.

In December 1960, while much text was redacted, the NSA history indicates there was major concern, about a Soviet airlift of supplies, and a "real concern that either the Soviets or the Chinese Communists, or both, would go beyond the supply flights and directly intervene in the fighting. On 14 December 1960, the NSA director, VADM Laurence L. Frost, institute a SIGINT Readiness Condition BRAVO on a theaterwide level throughout the Far East." The nature of BRAVO was not given, and the theater went back to ALPHA, apparently the lowest, by February 1961, when the intelligence community (IC) decided there was no chance the Soviets or PRC would join the fighting.[8]

By the end of the year, NSA estimated that the number of stations had quadrupled, with the communications activity in the Saigon area growing sixfold or sevenfold. The increased communications activity, according to the history, was so striking that Allen W. Dulles, the Director of Central Intelligence and head of the intelligence community, personally went to President John F. Kennedy, in January 1961, to brief him on the increase.

A section entitled "SIGINT and the Attempted Coups against Diem, 1960-1962", opens, on 11 November 1961, with the sounds of a coup attempt in Saigon. "Diem's luck held. The coup leaders were disorganized and amateurish. Rather than seize the palace [where Diem and his brother were barricaded], they preferred to talk. They also failed to capture the radio stations and other communications centers and failed to set up roadblocks..." and other obstacles to loyalist troops, who caused the coup members to flee, often to Cambodia. "American SIGINT had been surprised by the coup, as had American intelligence in general. In the coup's aftermath, SIGINT discovered, through decrypted VC regional headquarters messages, that the communists were taking an active interest in the failed coup, learning valuable lessons from its shortcomings, which would translate into plans to take advantage of any future maneuvers against Diem.[9]

Intercepts also made it clear that the attempted coup by paratroopers had surprised the Communists as much as Diem. "In the mad scramble for positioning that followed, the Viet Cong in the Nam Bo [Saigon] region directed subordinate elements to help soldiers, officers and others (politicians and security personnel) involved in the coup to escape."[9] This was followed by long redactions, and then the question, "Were the Communists on to something? There is no doubt that they were correct in their assessment that the Americans were disillusioned with Diem's failure to select a course of social reform and stick with it." They believed the Americans were contacting dissidents and planning new coups, but NSA states there was no evidence of American involvement; the South Vietnamese were more than capable of planning their own.

The history mentions that Diem's security organs were given a free hand by Ordnance Number 6 of January 1956, putting anyone deemed a threat to the defense of the state and public safety," at least in house arrest. A quote from Life magazine, generally considered friendly to Diem, suggested that a substantial number of non-communists had been arrested. This is followed by a brief note, "Yet in that same process of neutralizing opposition, Diem set the seeds for his own downfall." This followed by long redactions. Both Diem and the US Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG), according to the NSA history, felt the communists were going into "last gasps" in late 1959.[9]

Background: SIGINT and Building the Ho Chi Minh Trail

Hanyok writes that the 559th was variously known as a Transportation Group, Division, or Regiment. It had two subordinate regiments, the 70th and 71st, composed of truck, roadbuilding, and other operational functions. The 559th itself was subordinated to the General Directorate Rear Services (GDRS). From the SIGINT standpoint, the Trail began at two major supply-heads, Vinh Linh and Dong Hoi, which were the intermediate headquarters running the infiltration-associated radio nets from 1959 until late 1963. They disappeared in September 1963, although Vinh Linh became the headquarters of the 559th.

Multinational SIGINT planning, 1961

In January 1961, while the Vietnam embassy and military group prepared a counterinsurgency plan, the SIGINT community did its own planning. The first review of the situation assumed limited support to the ARVN COMINT teams. Essentially, the policy was that the South Vietnamese would be trained in basic direction finding using "known or derived" technical information, but, for security reasons, COMINT that involved more sophisticated analysis would not be shared. It was also felt that for at least the near term, ARVN COMINT could not provide meaningful support, and the question was presented, to the State Department, if it was politically feasible to have US direction-finding teams operate inside South Vietnam. The March 1961 plan included both tactical support and a strategic COMINT mission collection NVA data for NSA.

Eventually, the idea was that the South Vietnamese could intercept, but send the raw material to the US units for analysis. Two plans were created, WHITEBIRCH to increase US capability throughout the region but emphasizing South Vietnam, and SABERTOOTH to train ARVN personnel in basic COMINT. Concerns over ARVN security limited the information given them to non-codeword SECRET information. The first step in WHITEBIRCH was the 400th ASA Special Operations Unit (Provisional), operating under the cover name of the 3rd Radio Research Unit (RRU).[8]

US Deployment and Casualty (1960)

The 3rd RRU soon had its first casualty, SP4 James T. Davis, killed in an ambush.[7] Soon, it was realized that thick jungle made tactical ground collection exceptionally dangerous, and direction-finding moved principally to aircraft platforms[10].

NSA's Internal Security, Domestic Surveillance, and Western Counterespionage

For several years, "the fact of" the existence of NSA was not acknowledged, and for many years thereafter, one of the Washington area sayings was that the initials stood for "Never Say Anything", and the physical security of the campus was far greater than that at CIA. In spite of that attitude, however, there were several severe security breaches by staff working as Soviet defectors in place, or people who defected with maximum publicity.

NSA also engaged in questionably legal surveillance of civilian international traffic either originating or terminating in the United States.

Weisband

ASA in the post-World War II period had broken messages used by the Soviet armed forces, police and industry, and was building a remarkably complete picture of the Soviet national security posture. It was a situation that compared favorably to the successes of World War II. Then, during 1948, in rapid succession, every one of these cipher systems went dark, as a result of espionage by a Soviet agent, William Weisband. NSA suggests this may have been the most significant loss in US intelligence history. [4]

Martin and Mitchell

William Martin and Bernon Mitchell were NSA mathematicians, regarded highly for their scientific insight, but generally have been accepted to have odd socialization. [11] In 1960, they left on vacation, and eventually showed up in a Soviet press conference, speaking of the evils of the NSA. At the time, it was widely rumored that they were homosexual, but new evidence suggests while they may have been social misfits, there is little evidence they were gay. The Seattle Times' obtained files that said

"Beyond any doubt," the unnamed author of a then-secret NSA study on the damage done by the defection wrote in 1963, according to the recently released documents, "no other event has had, or is likely to have in the future, a greater impact on the Agency's security program."

Dunlop

US domestic surveillance

During this period, several programs, potentially in violation of its foreign intelligence charter, the NSA (and its AFSA predecessor) monitored international telegram and selected voice communications of American citizens[12].Project SHAMROCK, started during the fifties under AFSA, the predecessor of NSA, and terminated in 1975, was a program in which NSA obtained copies, without a warrant, of telegrams sent by international record carriers. The related Project MINARET intercepted voice communications of persons of interest to US security organizations of the time, including Malcolm X, Jane Fonda, Joan Baez, and Martin Luther King.

Western counterespionage

From 1943 to 1980, the VENONA project, principally a US activity with support from Australia and the UK, recovered information, some tantalizingly only in part, from Soviet espionage traffic. See article on VENONA. VENONA gave substantial information on the scope of Soviet espionage against the West, but critics claim some messages have been interpreted incorrectly, or are even false. Part of the problem is that certain persons, even in the encrypted traffic, were identified only by code names such as "Quantum". Quantum was a source on US nuclear weapons, and is often considered to be Julius Rosenberg. The name, however, could refer to any of a number of spies.

Collection methods advance

Before satellite SIGINT was practical, US information about Soviet radar stopped about 200 miles inland from the coastline. After these space systems went into service, effectively all radars on the Soviet landmass became known to NSA. They informed the Strategic Air Command with the technical details and locations of air defense radars, which went into planning attack routes of the Single Integrated Operational Plan (SIOP), the master set of plans for nuclear warfare. They provided operational information to Navy commanders. Coupled with IMINT from CORONA, they helped CIA, DIA and other elements of the intelligence community understand the overall Soviet threat.

There were still specific cases where aircraft were needed -- and where crews died. UAVs became increasingly more attractive for such high-risk missions.

Space systems begin

The first successful SIGINT satellites, known informally as "Ferrets", were classified payloads aboard the Galactic Radiation and Background (GRAB), designed by the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory. GRAB had an unclassified experiment called Solrad, and an ELINT package called TATTLETALE. See National Reconnaissance Office (NRO), an agency even more secretive than NSA for more detail on GRAB/TATTLETALE. As the military cryptologic agencies, using ground, sea, and aircraft platforms, actually intercepted and processing raw SIGINT material to be forwarded to Fort Meade, the NRO was responsible for similar capture, but from satellites that NRO was responsible for launching and operating.

According to the NRO, the incremental upgrade of GRAB's Tattletale package was POPPY. The second program, Poppy, operated from 1962 to 1977. The "fact of" the Poppy program, along with limited technical information, was declassified in 2004. [13] At least three NRO operators did the preliminary processing of the POPPY data, one measuring the orbital elements of the satellite and the selected polarization, while the second operator identified signals of interest. The third operator did more detailed, non-real-time, analysis of the signal, and transmitted information to NSA.

After these space systems went into service, most radars on the Soviet landmass became known to NSA. NSA, in turn, provided the characteristics of the Soviet air defense network to the Single Integrated Operational Plan (SIOP) staff, and to Navy commanders who would operate in Soviet waters. Coupled with IMINT from CORONA, they helped CIA, DIA and other elements of the intelligence community understand the overall Soviet threat.

The U.S. embarked on a new generation of reconnaissance satellites, Air Force Project WS-117L, approved by President Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1954. This program was focused on IMINT and MASINT, but some satellites would also carry signal intercept subsystem under Project PIONEER FERRET. [5] By 1959, WS-117L had split into three programs: [14] The major programs were:

- Discoverer, the unclassified name for the CORONA IMINT satellite

- Satellite and Missile Observation System (SAMOS)(IMINT)

- Missile Defense Alarm System (MIDAS), a nonimaging staring infrared MASINT system

The first experimental ELINT package would fly aboard a photoreconnaissance satellite, Discoverer-13, in August 1960. Translated from the Russian, it was equipped with "Scotop equipment was intended to record the signals of Soviet radars which were tracking the flight of American space objects." [5]

Soviet sources state the first specialized ELINT satellites, which received the designation of "Ferret," was begun in the USA in 1962.[5] In actuality, the first successful SIGINT satellite was the U.S. Navy's Galactic Radiation and Background (GRAB), designed by the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory. GRAB had an unclassified experiment called Solrad, and an ELINT package called Tattletale. Tattletale was also called Canes; CANES was also the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) sensitive compartmented information (SCI) codeword for the control system overall program. GRAB intercepted radar pulses as they came over the horizon, translated the frequency, and retransmitted each pulse, with no further processing, to ground receiving sites.[13] GRAB operated from 1960 to 1962.[15] Again examining space-based SIGINT through Soviet eyes, "The tasks of space-based SIGINT were subdivided into two groups: ELINT against antiaircraft and ABM radars (discovery of their location, operating modes and signal characteristics) and SIGINT against C3 systems. In order to carry out these tasks the US developed ... satellites of two types:

- small ELINT satellites which were launched together with photoreconnaissance satellites into initially low orbits and then raised into a polar working orbit at an altitude of 300 to 800 km using on-board engines

- heavy (1 to 2 tonne mass) "SIGINT" (possibly the translator's version of COMINT?) satellites, which were put into orbit at an altitude of around 500 km using a Thor-Agena booster. The Soviet source described the satellites of the late sixties as "Spook Bird" or CANYON [5], which was the predecessor to the production RHYOLITE platforms. This was not completely correct if the Soviets thought these were heavy ELINT satellites; CANYON was the first COMINT satellite series, which operated from 1968 to 1977.

According to the NRO, the incremental upgrade of GRAB's Tattletale package was POPPY. The second program, Poppy, operated from 1962 to 1977. The "fact of" the Poppy program, along with limited technical information, was declassified in 2004. [13] At least three NRO operators did the preliminary processing of the POPPY data, one measuring the orbital elements of the satellite and the selected polarization, while the second operator identified signals of interest. The third operator did more detailed, non-real-time, analysis of the signal, and transmitted information to NSA.

In the EC-121 shootdown incident of 15 April 1969, an EC-121M of the U.S. Navy's Fleet Airborne Reconnaissance Squadron One (VQ-1) Vietnam, took off on a routine SIGINT patrol under the BEGGAR SHADOW program. North Korean air search radar was monitored by the USAF 6918th Security Squadron in Japan, and Detachment 1 6922nd Security Wing at Osan Air Base in Korea, and the Naval Security Group at Kamiseya, Japan. The EC-121M was not escorted. When US radar detected the takeoff of North Korean interceptors, and the ASA unit lost touch, ASA called for fighters, but the EC-121M never again appeared on radar. 31 crewmen were lost.

In response to this threat on what had been considered a low-risk mission, Ryan was tasked to develop the AQM-34Q was the SIGINT version of the AQM-34P, with antennas along the fuselage. Underwing fuel tanks were added to this model, and the AQM-34R updated the electronics and had standard underwing tanks.[16]

CIA provides additional collection approaches

While the Service Cryptologic Elements (SCE) provided intercepts from ground, air and sea platforms were U.S. overt forces could go, and NRO provided satellite basis, cooperation between NSA and CIA's clandestine operations personnel found ways to emplace, secretly, SIGINT sensors behind the Iron Curtain.

Also in 1962, the Central Intelligence Agency, Deputy Directorate for Research, formally took on ELINT and COMINT responsibilities[17]. "The consolidation of the ELINT program was one of the major goals of the reorganization....it is responsible for:

- Research, development, testing, and production of ELINT and COMINT collection equipment for all Agency operations.

- Technical operation and maintenance of CIA deployed non-agent ELINT systems.

- Training and maintenance of agent ELINT equipments

- Technical support to the Third Party Agreements.

- Data reduction of Agency-collected ELINT signals.

- ELINT support peculiar to the penetration problems associated with the Agent's reconnaissance program under NRO.

- Maintain a quick reaction capability for ELINT and COMINT equipment."

"CIA's Office of Research and Development was formed to stimulate research and innovation testing leading to the exploitation of non-agent intelligence collection methods....All non-agent technical collection systems will be considered by this office and those appropriate for field deployment will be so deployed. The Agency's missile detection system, Project [deleted] based on backscatter radar is an example. This office will also provide integrated systems analysis of all possible collection methods against the Soviet antiballistic missile program is an example." [17]. It is not clear where ELINT would end and MASINT would begin for some of these projects, but the role of both is potentially present. MASINT, in any event, was not formalized as a US-defined intelligence discipline until 1986.

US Submarine SIGINT begins

Under the code names HOLYSTONE, PINNACLE, BOLLARD, and BARNACLE, began in 1959, US submarines infiltrated Soviet harbors to tap communications cables and gather SIGINT. They also had a MASINT mission against Soviet submarines and missiles. The program, which went through several generations, ended when compromised, by Ronald Pelton, in 1981.[18]

Early UAV development

Unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV), called "drones" at the time, were introduced quite early and served a number of purposes, although SIGINT was not the first mission. [16] won the US Air Force competition for the Q-2 jet-propelled aerial target. Known as the Q-2A Firebee, the jet-propelled UAV, launched by a rocket and recovered by parachute, was also bought by the Navy and Army.

In 1961, the Air Force requested a reconnaissance version of what was then designated the BQM-34A, which resulted in the Firebee Model 147A, to be designated the AQM-34.[16] This UAV looked like its target version, but carried more fuel and had a new navigation system. These reconnaissance drones were air-launched from a DC-130 modified transport. Like all subsequent versions of this UAV, it was air-launched from underneath the wing of a specially modified Lockheed DC-130 Hercules, rather than ground-launched with rocket assistance. These are thought to have been operationally for IMINT, although SIGINT was considered, as more aerial US reconnaissance platforms do SIGINT than IMINT, and most IMINT platforms, such as the U-2 and SR-71 also have SIGINT capability. Drones of this version were to be used in the Cuban Missile Crisis.[16]

The Cuban Crisis and the hotter part of the Cold War

While the start of the Cuban Missile Crisis came from IMINT showing Soviet missiles under construction, SIGINT had had an earlier role in suggesting that increased surveillance of Cuba might be appropriate. NSA had intercepted suspiciously blank shipping manifests to Cuba, and, through 1961, there was an increasing amount of radio chatter suggestive of Cuba receiving both Soviet weapons and personnel. The weapons could be used offensively as well as defensively[19].

In September and October 1962, SIGINT pointed to the completion of a current Soviet air defense network in Cuba, presumably to protect something. The key U-2 flight that spotted the ballistic missiles took place on October 15. While the IMINT organizations were most critical, an anecdote of the time, told by Juanita Moody, the lead SIGINT specialist for Cuba, that the newly appointed Director of NSA, LTG Gordon Blake, came by to see if he could help. "She asked him to try to get additional staff to meet a sudden need for more personnel. Shortly she heard him on the telephone talking to off-duty employees: "This is Gordon Blake calling for Mrs. Moody. Could you come in to work now?"

Two RB-47H aircraft, of the 55th Reconnaissance Wing, during the Cuban Missile Crisis were modified to work with Ryan AQM-34 SIGINT UAVs,[16] still launched from DC-130s. The UAVs carried deceptive signal generators that made them appear to be the size of a U-2, and also carried receivers and relays for the Soviet SA-2 surface-to-air missiles on Cuba. In real time, the UAVs relayed the information to the RB-47, which was itself using ELINT sensors against the radar and SA-2 command frequencies. Essentially, the UAV was carrying out a "ferret" probe intended to provoke defensive response, but not jeopardizing the lives of pilots. This full capability was only ready in 1963, and the original scenario no longer held.

During the Crisis, after a U-2 was shot down, RB-47H's of the 55th wing began flying COMMON CAUSE missions, with other US aircraft, to identify any Cuban site that fired on a US plane. The Cubans, however, believed the US threat that such a site would immediately be attacked, and withheld their fire. Crews began calling the mission, as a result, "Lost Cause".[20]

Tactical Naval SIGINT monitored stopped Soviet transports, when it was unknown if they would challenge the naval quarantine. Direction finding confirmed they had turned around. [19]

While certain drone functions failed in the Cuban crisis, they were soon ready for service. DC-130 launchers and controllers were deployed to Kadena in Okinawa, and the Bien Hoa in Vietnam. The real-time telemetry, hoped for during the Cuban crisis, was now a reality, and RB-47H ELINT aircraft were dedicated to Southeast Asian operations.

RC-135Ms were flying at the same time, but primarily against China and Russia. Eventually, their missions focused on Southeast Asia.[20]

US-RVN doctrine, 1961

In January 1961, while the Vietnam embassy and military group prepared a counterinsurgency plan, the SIGINT community did its own planning. The first review of the situation assumed limited support to the ARVN COMINT teams. Essentially, the policy was that the South Vietnamese would be trained in basic direction finding using "known or derived" technical information, but, for security reasons, COMINT that involved more sophisticated analysis would not be shared. It was also felt that for at least the near term, ARVN COMINT could not provide meaningful support, and the question was presented, to the State Department, if it was politically feasible to have US direction-finding teams operate inside South Vietnam. The March 1961 plan included both tactical support and a strategic COMINT mission collection NVA data for NSA.

Eventually, the idea was that the South Vietnamese could intercept, but send the raw material to the US units for analysis. Two plans were created, WHITEBIRCH to increase US capability throughout the region but emphasizing South Vietnam, and SABERTOOTH to train ARVN personnel in basic COMINT. Concerns over ARVN security limited the information given them to non-codeword SECRET information. The first step in WHITEBIRCH was the 400th ASA Special Operations Unit (Provisional), operating under the cover name of the 3rd Radio Research Unit (RRU).[8]

The 3rd RRU soon had its first casualty, SP4 James T. Davis, killed in an ambush.[7] Soon, it was realized that thick jungle made tactical ground collection exceptionally dangerous, and direction-finding moved principally to aircraft platforms[10].

Although SIGINT personnel were present in 1960, Gilbert breaks the ASA involvement in Vietnam into four chronological phases,[7] which do not match the more recent NSA history by Hanyok, which is less focused on events with the US military. [9]

- The Early Years: 1961-1964, characterized by direction-finding and COMSEC, ending with the Gulf of Tonkin Incident. This partially overlaps the period of "SIGINT and the Attempted Coups against Diem, 1960-1962"[9]

- The Buildup: 1965-1967, with cooperation at the Corps/Field Force level, and the integration of South Vietnamese linguists. Major ASA units at this time were the 509th Radio Research Group and 403d RR (Radio Research) SOS (Special Operations Detachment)[7]

- Electronic Warfare: 1968-1970, with substantial technical experimentation

- Vietnamization: 1971-1973, as the mission shifted back to training, advising, and supporting South Vietnamese units.

Drones evolve and the impact of the EC-121 shootdown (1967-1971)

A major advance for high-risk IMINT and SIGINT missions was the high-altitude AQM-34N[16] COMPASS DAWN, which flew as high as 70000 ft and had a range over 2,400 miles. AQM-34N's flew 138 missions between March 1967 and July 1971, and 67% were parachute-recovered with the new Mid-Air Retrieval System, which used a helicopter to grab the parachute cable in mid-air. While this had an IMINT mission, the potential of high altitude for SIGINT over a wide area was obvious.

In the EC-121 shootdown incident of 15 April 1969 , an EC-121M of the U.S. Navy's Fleet Airborne Reconnaissance Squadron One (VQ-1) Vietnam, took off on a routine SIGINT patrol under the BEGGAR SHADOW program. North Korean air search radar was monitored by the USAF 6918th Security Squadron in Japan, and Detachment 1 6922nd Security Wing at Osan Air Base in Korea, and the Naval Security Group at Kamiseya, Japan. The EC-121M was not escorted. When US radar detected the takeoff of North Korean interceptors, and the ASA unit lost touch, ASA called for fighters, but the EC-121M never again appeared on radar. 31 crewmen were lost.

In response to this threat on what had been considered a low-risk mission, Ryan was tasked to develop the AQM-34Q was the SIGINT version of the AQM-34P, with antennas along the fuselage. Underwing fuel tanks were added to this model, and the AQM-34R updated the electronics and had standard underwing tanks.[16]

References

- ↑ National Security Agency, Mission Statement

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Hanyok, Robert J. (2002), Chapter 1 - Le Grand Nombre Des Rues Sans Joie: [Deleted and the Franco-Vietnamese War, 1950-1954], Spartans in Darkness: American SIGINT and the Indochina War, 1945-1975, Center for Cryptologic History, National Security Agency

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Thomas L. Burns (1990), The Origins of the National Security Agency, 1940-1952, National Security Agency

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Hatch, David A.; Robert Louis Benson. The Korean War: The SIGINT Background. National Security Agency.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Andronov, A. (1993), Thomson, Allen (translator), ed., "American Geosynchronous SIGINT Satellites", Zarubezhnoye voyennoye obozreniye

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 John, Pike, DGSE - General Directorate for External Security (Direction Generale de la Securite Exterieure)

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 7.12 Gilbert, James L. (2003). (Review of) The Most secret War: Army Signals Intelligence in Vietnam.. Pittsburgh, PA: Military History Office, US Army Intelligence and security Command..

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 Hanyok, Robert J. (2002), Chapter 3 - "To Die in the South": SIGINT, the Ho Chi Minh Trail, and the Infiltration Problem, [Deleted 1968], Spartans in Darkness: American SIGINT and the Indochina War, 1945-1975, Center for Cryptologic History, National Security Agency

- ↑ 9.00 9.01 9.02 9.03 9.04 9.05 9.06 9.07 9.08 9.09 9.10 9.11 9.12 9.13 9.14 9.15 9.16 Hanyok, Robert J. (2002), Chapter 2 - The Struggle for Heaven's Mandate: SIGINT and the Internal Crisis in South Vietnam, [Deleted 1962], Spartans in Darkness: American SIGINT and the Indochina War, 1945-1975, Center for Cryptologic History, National Security Agency

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Knight, Judson, Army Security Agency. Retrieved on 2007-10-08

- ↑ Anderson, Rick (July 18, 2007), Seattle Weekly

- ↑ Senate Select Committee to Study Government Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities (OCTOBER 29 AND NOVEMBER 6, 1975), The National Security Agency and Fourth Amendment Rights. Retrieved on 2007-12-07

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 MacDonald, Sharon K. & Moreno (2005), Raising the Periscope... Grab and Poppy, America's early ELINT Satellites, U.S. National Reconnaissance Office

- ↑ U.S. Air Force, Chapter V, Space Systems

- ↑ Hall, R. Cargill, The NRO at Forty: Ensuring Global Information Supremacy

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 16.6 RYAN AQM-34G - R. Retrieved on 2007-10-12.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Central Intelligence Agency (May 1998), Deputy Director for Research. Retrieved on 2007-10-07

- ↑ Jeffrey Richelson (1989), The US Intelligence Community, 2nd Edition, Chapter 8, Signals Intelligence, Richelson 1989. Retrieved on 2007-10-19

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Johnson, Thomas R. & David A. Hatch (May 1998), NSA and the Cuban Missile Crisis. Retrieved on 2007-10-07

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Bailey, Bruce M (1995), The RB-47 and RC-135 in Vietnam. Retrieved on 2007-10-12

External Links

Executive Order Executive Order 12333--United States intelligence activities http://www.archives.gov/federal-register/codification/executive-order/12333.html