Battle of Leyte Gulf

The Battle of Leyte Gulf in October 23-26, 1944, was an American victory over Japan in the largest naval battle in history. Although the Japanese came surprising close to inflicting a major defeat on the Americans, at the last minute the tide turned and the U.S. Navy sank virtually all of Japan's naval power. Part of World War II, Pacific it involved a complex overlapping series of engagements fought off the Philippine island of Leyte, which the U.S. Army had just invaded. The army forces were highly vulnerable to naval attack, and the Japanese goal was to inflict massive destruction on them. Two American fleets were involved, the Seventh and Third, but they were independent and did not communicate well. The Japanese communication system was even worse, and the Japanese army and navy did not cooperate.

Plans

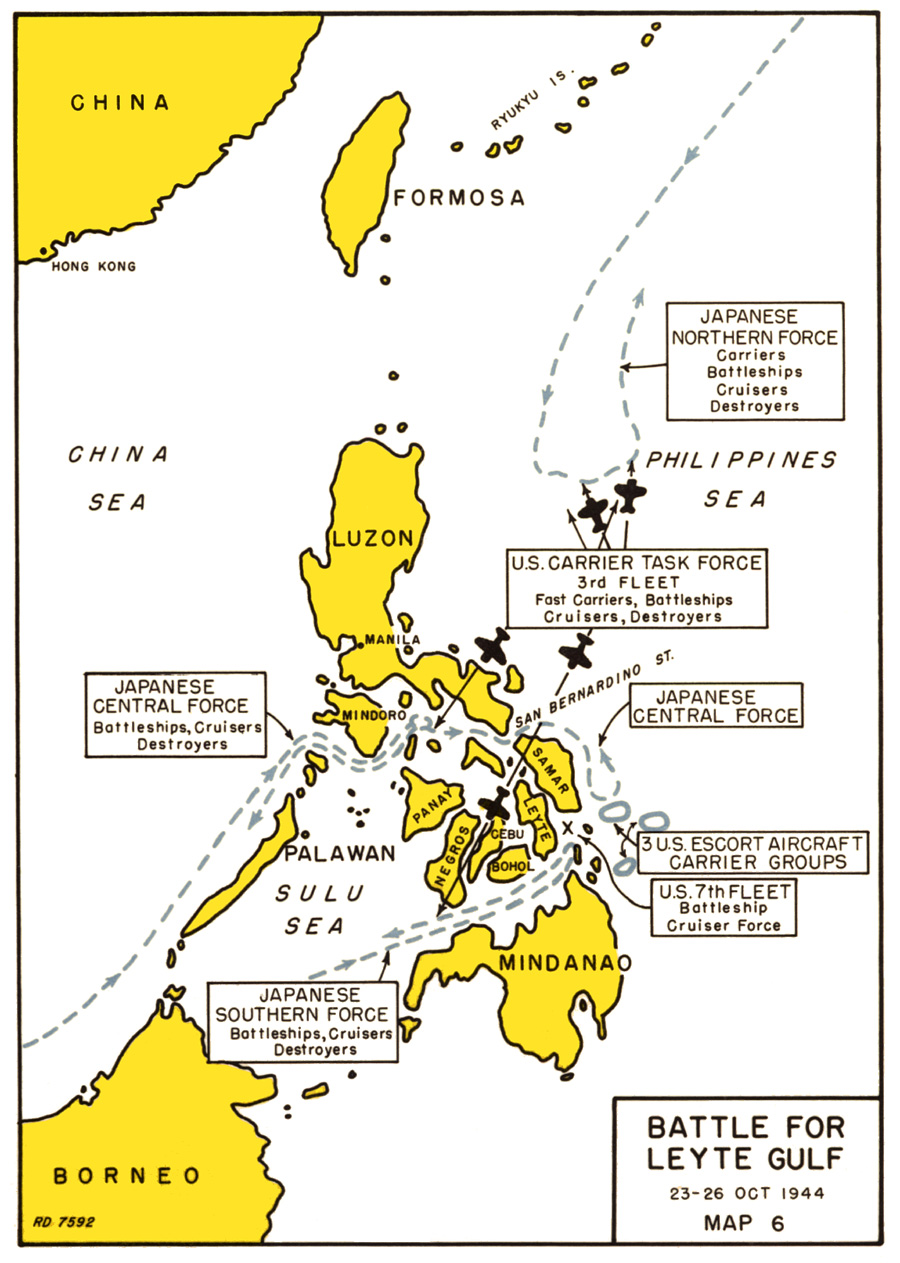

In 1944 the U.S. Navy under Admiral Chester Nimitz jumped from island to island across the central Pacific, leapfrogging over the strongest Japanese holdings. General Douglas MacArthur's army troops were simultaneously approaching Japan from the south. The ultimate goal was to invade the home islands, but to get within range the Philippines first had to be reconquered. Wading through the surf at the island of Leyte--with 174,000 soldiers--MacArthur had returned as promised. Admiral Toyoda (Commander in Chief of the remaining fleets) had to defend the Philippines, but he knew his navy was hopelessly outclassed, outgunned and outnumbered by more than 3 to 1. Fuel oil was running short, and carrier aviation had almost ceased to exist. But he and Admiral Ozawa drew up an ingenious plan that exactly identified the Yankee weak point and could exploit it with a smashing defeat that might force Washington to negotiate peace terms. The American weakness was divided command--two fleets were guarding Leyte: The Seventh Fleet under Vice Admiral Thomas Kincaid, reported to MacArthur; the much stronger Third Fleet under Admiral William Halsey reported to Nimitz. The Joint Chiefs in Washington had never been able to agree on a single commander for the Pacific. The Navy wanted Nimitz; the Army insisted on MacArthur. Japan's plan: send in three fleets--two to lure away the uncoordinated guards, the third to sink the transports, support ships and massacre the invaders on the beaches.

Admiral William "Bull" Halsey commanded the massive Third Fleet, and he believed fervently in the carrier doctrine.[1] He proved to be as aggressive as Spruance was cautious--his goal was to destroy the Japanese strategic forces, that is their carriers. Admiral Thomas Kinkaid's Seventh fleet (reporting to MacArthur) comprised TF (Taffy) 1, 2 and 3, with 16 small, slow, unarmored escort carriers designed as platforms for close ground support, plus 9 small destroyers. Under Kinkaid, Admiral Jesse Oldendorf had 6 old battleships (some resurrected from Pearl Harbor), plus 9 cruisers and 66 destroyers; Oldendorf's armada was designed for bombarding beaches, not for fighting an enemy fleet.

The battle

To reach the Leyte beaches, Japanese forces would have to come through either San Bernardino Strait to the north, covered by Halsey, or Surigao Strait to the south, covered by Oldendorf. On October 24 Admiral Kurita headed toward San Bernardino, and Admiral Nishimura headed for Surigao. Oldendorf demonstrated a textbook exercise in how to sink an enemy fleet. His ships steamed back and forth across the top of a "T" while Nishimura's ships came up the stem of the "T" one by one and were sunk. Only one escaped. It was like a carnival shooting gallery, with Oldendorf throwing ball after ball and winning all the Kewpie dolls until he had nearly exhausted his ammunition. Oldendorf had been tricked out of the real fight. Simultaneously Halsey's planes blasted away at Kurita, who finally turned tail and retreated. So overconfident were the Yanks that they reported far more damage than they actually inflicted. Halsey was an aviator who thought battleships were obsolete dinosaurs, so he wrote Kurita's force off--and refused to listen to aides who had doubts.

Late on the night of the 24th Halsey was puzzled about the Japanese carriers--they must be somewhere, but he could not find them. They were his main objective, according to Mahanian doctrine of great fleet battles. In fact Ozawa with his nearly empty carriers was making smoke, breaking radio silence on various frequencies, and sending escorts out ahead--his fleet was the decoy and its mission was to be spotted. Finally Halsey did locate Ozawa and set chase to the north. Halsey decided to sink the carriers in the morning. When Kinkaid finally bothered to check to be sure Halsey was still covering the San Bernardino Strait, he was dumbfounded to be told "no"--Halsey was out chasing carriers. In fact Kurita had circled about and was now roaring though San Bernardino Strait with four battleships, eight cruisers and eleven destroyers, all headed straight toward MacArthur's defenseless troops and transports on the Leyte beaches. Kinkaid desperately called for help; Halsey said he was busy, use Oldendorf's battleships. But they're too far away and low on ammunition! Suddenly, Nimitz, who had been eavesdropping from Pearl Harbor intervened. Humiliated, Halsey sent half his powerful force back, but it was too late.

Only Admiral "Ziggy" Sprague's Taffy 3--a handful of CVEs and destroyers designated TF3--blocked Kurita's fleet. They had fighter planes but no heavy guns, no armor-piercing bombs, no defensive armor, and little speed. Kurita had the massive firepower to sink Taffy 3 in ten minutes. Sprague, resigned to his own utter destruction, seized the initiative from Kurita by making 8 key decisions in 15 minutes. Taffy fought back in desperation. Three small destroyers and four even smaller destroyer escorts made suicide runs at the giant battleships. The little carriers retreated south into the wind, launching their fighters to attack Kurita again and again, while light bombers without bombs made heroic fake attacks to force Kurita to dodge and slow down. Kurita misjudged the situation. Instead of concentrating on his main mission of attacking the beaches, and detailing a few cruisers to finish off Sprague, he decided Taffy 3 was the main enemy and launched all his warships in uncoordinated pell mell attacks. Then in the strangest move of the strangest battle of the 20th century, Kurita panicked. Japanese radio gear was so poor he had not received Ozawa's message that Halsey had been successfully decoyed out of action, but he did hear Kinkaid's uncoded yells for help. Kurita assumed he would soon be surrounded by Halsey's huge fleet. The Americans appeared ten feet tall--the little Yankee destroyers were reported to be large cruisers. Despite his vastly overwhelming firepower and speed, Kurita had ordered defensive zigzagging, which nullified his advantages. When he failed to gain on the slow CVEs, he assumed they must be Halsey's fast carriers. With his big battleships closing at point blank range against the overwhelmed Yankees, with a stunning victory almost in his grasp, Kurita suddenly ordered retreat; he turned and escaped back through San Bernardino Strait. By assuming the worst about the enemy instead of concentrating on his own capabilities, he failed the test of battle. A more subtle explanation is that Kurita accepted the new doctrine that his battleships were obsolete and could not defeat fleet carriers of the sort he mistakenly perceived in front of him; therefore he might as well quit. He did not realize that no big carriers were around. The old doctrine of the power of big guns had been reaffirmed by Oldendorf's smashing victory, and might also have been reaffirmed by Kurita's battleships if only he had followed the original plan and not succumbed to defeatism.

Results

In the greatest and most complex naval battle ever fought, half the Japanese Navy went to the bottom; US losses were light, and the troops on the beaches were untouched. Of the 282 warships engaged (216 American, 2 Australian, and 64 Japanese), the Japanese lost 4 carriers, 3 battleships, 10 cruisers, and 11 destroyers. American losses totaled one light carrier, two escort carriers, and three destroyers.

Halsey always defended his decision to abandon Leyte; its defense was Kinkaid's job and his mission was strategic. The overwhelming weight of opinion has been that Ozawa outfoxed Halsey, who clung too tenaciously to his carrier doctrine, and who failed to gather and act on the information that was available to him. Halsey's blunder might have cost tens of thousands of lives, or at least delayed the invasion of the Philippines for months, but his luck made him the victor in the biggest naval battle of all time.

Bibliography

- Cutler, Thomas J. The Battle of Leyte Gulf: 23-26 October 1944 (2001) 343pp, major scholarly study; uses oral histories

- Dull, Paul S. A Battle History of the Imperial Japanese Navy (1941 - 1945), (1978) (ISBN: 0870210971), brief summary

- Ireland, Bernard, and Howard Gerrard. Leyte Gulf 1944 (2006) excerpt and text search

- Morison, Samuel Eliot. History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Vol. 12, Leyte. (1958). official Navy history

- Potter, E. B. Bull Halsey (1985). standard biography

- Sears, David. The Last Epic Naval Battle: Voices from Leyte Gulf (2005), 210pp; based on oral histories; online edition

- Spector, Ronald. Eagle Against the Sun: The American War with Japan (1985), brief summary

- Toland, John. The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire, 1936-1945 (1970); Pulitzer Prize history from Japanese perspective; excerpt and text search

- Willmott, H. P. The Battle Of Leyte Gulf: The Last Fleet Action (2005) 398pp, advanced history

- Woodward, C. Vann. The Battle for Leyte Gulf: The Incredible Story of World War II's Largest Naval Battle (1947, reprint 2007) excerpt and text search; also online edition

Primary Sources

See also

Online resources

notes

- ↑ Halsey and Raymond Spruance, and their respective staffs, rotated in command of the same fleet. When Spruance was aboard, the numbering was Fifth Fleet, and Task Force 58; when Halsey was in charge, the same fleet was renamed the Third Fleet, and Task Force 38. The Japanese incorrectly concluded there were two separate fleets involved.