Glucostatic theory of appetite control

For the course duration, the article is closed to outside editing. Of course you can always leave comments on the discussion page. The anticipated date of course completion is 01 February 2011. One month after that date at the latest, this notice shall be removed. Besides, many other Citizendium articles welcome your collaboration! |

Begin your article with a brief overview of the scope of the article on interest group. Include the article name in bold in the first sentence.[1]

Remember you are writing an encyclopedia article; it is meant to be readable by a wide audience, and so you will need to explain some things clearly, without using unneccessary jargon. But you don't need to explain everything - you can link specialist terms to other articles about them - for example adipocyte or leptin simply by enclosing the word in double square brackets.

You can write your article directly onto the wiki- but at first you'll find it easier to write it in Word and copy and paste it onto the wiki.

Construct your article in sections and subsections, with headings and subheadings like this:

Introduction

Since the early twentieth century, there has thought to have been a link between blood glucose and appetite. In 1916, Carlson suggested that glucose could serve as a signal for meal initiation (low levels) and meal termination (high levels) (Mobbs, 2005). But it was not until the 1950s that Mayer put forward the glucostatic hypothesis. Originally it was thought that a rise in plasma glucose, for example after a meal, was sensed by neurons in the hypothalamus. These neurons which contained “glucoreceptors” then signalled for meal termination. Glucose, therefore, was thought of as a satiety factor (Flint, 2006).

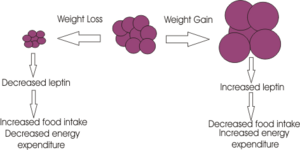

However, this theory has been debated for many years. While numerous studies produce results which appear to support Mayer’s hypothesis, a large number also refute it and compelling evidence has yet to be found. The theory, which was popular in the 1950s, was losing support by the 1980s. At this time, scientists were beginning to think that the control of appetite was a more complex mechanism that would have to depend on the integration of a number of signalling pathways. The glucostatic theory was not abandoned all together though as it was still thought to be important for short term appetite control. However, discoveries of peptides such as leptin became more likely candidates for long term appetite control.

Title of Subpart 1

Glucose homeostasis must be finely regulated by the absorption of food and the flow of recently stored energy substances through different metabolic pathways. Especially for the brain glucose, it has to be supplied continuously from the blood stream since there is no storage for sugar available in the brain. It is known that changes in glucose level elicit complex nuroendocrine responses that restore the blood sugar level to the optimum range. (Ritter, S. et al. 2006) It is traditionally believed that different regions of the forebrain; particularly the hypothalamus and the brain stem have important centres where are responsible for monitoring blood glucose level and regulating feeding. (Mayer, J. 1955) However, Ritter R. G. et al. claimed that glucoreceptor cells are located in the hindbrain. This means that the glucose sensing cells have a direct access to the central nervous system and could elicit immediate response to retain the physiological norm. (Ritter, R. C. et al. 1981) They also explained that the catecholamine neurons in the hindbrain help mediating responses to glucose deficiency by linking glucoceptor cells to forebrain and spinal neurons. This enables us to stimulate behavioural and hormonal responses that elevate blood sugar level. These include increased food intake, adrenal medullary secretion, corticosterone secretion and suppression of estrous cycles. Complex behaviours involved in activities such as detection and identification of food are mainly regulated by the forebrain. Her studies suggest that the hind brain mediates the motivation for these activities via the neuronal circuit activated by some of the glucose sensing cells. They hypothesised that the signals detected by the glucoceptors are projected to the hypothalamus via norepinephrine and epinephrine neurons in the hind brain. This motivation circuit would have been engaged the physical sign of energy deficiency with these behaviours. (Ritter, S. et al. 2006)

Title of Subpart 2

Title of Part 2

etc.

About References

To insert references and/or footnotes in an article, put the material you want in the reference or footnote between <ref> and </ref>, like this:

<ref>Person A ''et al.''(2010) The perfect reference for subpart 1 ''J Neuroendocrinol'' 36:36-52</ref> <ref>Author A, Author B (2009) Another perfect reference ''J Neuroendocrinol'' 25:262-9</ref>.

Look at the reference list below to see how this will look.[2] [3]

If there are more than two authors just put the first author followed by et al. (Person A at al. (2010) etc.)

Select your references carefully - make sure they are cited accurately, and pay attention to the precise formatting style of the references. Your references should be available on PubMed and so will have a PubMed number. (for example PMID: 17011504) Writing this without the colon, (i.e. just writing PMID 17011504) will automatically insert a link to the abstract on PubMed (see the reference to Johnsone et al. in the list.)

[4]

Use references sparingly; there's no need to reference every single point, and often a good review will cover several points. However sometimes you will need to use the same reference more than once.

How to write the same reference twice:

Reference: Berridge KC (2007) The debate over dopamine’s role in reward: the case for incentive salience. Psychopharmacology 191:391–431 PMID 17072591

First time: <ref name=Berridge07>Berridge KC (2007) The debate over dopamine’s role in reward: the case for incentive salience. ''Psychopharmacology'' 191:391–431 PMID 17072591 </ref>

Second time:<ref name=Berridge07/>

This will appear like this the first time [5] and like this the second time [5]

Figures and Diagrams

You can also insert diagrams or photographs (to Upload files Cz:Upload)). These must be your own original work - and you will therefore be the copyright holder; of course they may be based on or adapted from diagrams produced by others - in which case this must be declared clearly, and the source of the orinal idea must be cited. When you insert a figure or diagram into your article you will be asked to fill out a form in which you declare that you are the copyright holder and that you are willing to allow your work to be freely used by others - choose the "Release to the Public Domain" option when you come to that page of the form.

When you upload your file, give it a short descriptive name, like "Adipocyte.png". Then, if you type {{Image|Adipocyte.png|right|300px|}} in your article, the image will appear on the right hand side.

References

- ↑ See the "Writing an Encyclopedia Article" handout for more details.

- ↑ Person A et al. (2010) The perfect reference for subpart 1 J Neuroendocrinol 36:36-52

- ↑ Author A, Author B (2009) Another perfect reference J Neuroendocrinol 25:262-9

- ↑ Johnstone LE et al. (2006)Neuronal activation in the hypothalamus and brainstem during feeding in rats Cell Metab 2006 4:313-21. PMID 17011504

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 Berridge KC (2007) The debate over dopamine’s role in reward: the case for incentive salience. Psychopharmacology 191:391–431 PMID 17072591