Obesogenic environment

Helen Martin 19:05, 25 October 2011 (UTC)

For the course duration, the article is closed to outside editing. Of course you can always leave comments on the discussion page. The anticipated date of course completion is 01 April 2012. One month after that date at the latest, this notice shall be removed. Besides, many other Citizendium articles welcome your collaboration! |

The obesogenic environment encompasses the environmental features of modern lifestyles that are postulated to contribute to the increasing prevalence of obesity; in particular, it is thought that the wide availability of food that is energy dense, palatable and inexpensive, combined with increasingly sedentary habits, favour an excess of energy intake over expenditure.[1] Helen Martin 11:38, 22 October 2011 (UTC)

The obesogenic environment.

Over the past 40 years the prevalence of obesity has become a cause for concern, the dramatic rise in rates of obesity amongst both adults and children means that, across the world, 1.46 billions adults and 70 million children are estimated to be overweight or obese in 2008[2], so what is it that is making us fat?

In 2011 the leading medical journal The Lancet published a series of articles on obesity[2]; these made a number of suggestions as to why obesity rates have risen, and continue to rise, so rapidly. Perhaps it is our environment that is to blame, and that obesity represents ‘a normal reaction to an abnormal environment.[2]

The notion that the environment may be associated with obesity is not new, with Rimm and White arguing over 25 years ago that obesity was a product of the environment. However, the term 'obesogenic environment' has recently been defined as 'the sum of influences that the surroundings, opportunities, or conditions of life have on promoting obesity in individuals or populations'.

Modern lifestyles.

Chronic stress and obesity.

In the UK, the number of people reporting feeling stressed has doubled since the 1990’sCite error: Invalid <ref> tag; invalid names, e.g. too many, even though the hours spent at work in the UK is average amongst other European countries,[3] the amount of unpaid work, mainly caring for children and housework done predominately by women is above average compared to other countries within the EU[3]. This survey only took into account the working population, suggesting that even though, the amount of time spent at work hasn’t increased, juggling family commitments and employment may lead to increased rates of stress related ill health.

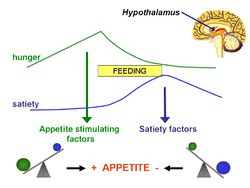

So, is it our fault we are getting fat? Experimental studies in laboratory animals show a clear relationship between stress and obesity; being chronically stressed increases the amount of 'comfort food' ingested by rats[4]. Chronic stress as opposed to acute stress, results in increased concentration of glucocorticoids (cortisol in humans and corticosterone in rodents) over a prolonged period of time[5]. High levels of glucocorticoid over a long period, rather than negatively feeding back on the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis reducing the amount of glucocorticoids produced, become excitatory [5]. This is important and accounts for the differences in the reaction between acute and chronic stress responses. Eating ‘comfort food’, defined as food high in carbohydrate and sugar,[4] is proposed to dampen down the HPA axis decreasing anxiety levels associated with the excitatory effect of prolonged high glucocorticoid levels. Increased cortisol levels correlate with obesity, as seen in Cushing’s disease where a pathological overproduction of cortisol because of abnormal stimulation of the HPA axis leads to abdominal obesity. This increase in cortisol is also seen in stress and depressed individuals as compared to a control group.[6] But which comes first, the increase in cortisol or the obesity? Adipose tissue contains the enzyme 11-beta hydroxysteroid type one which converts inactive cortisone to cortisol, the more adipose tissue you have the more conversion[6], thus breaking this cycle may be important in tackling obesity. There is also significant evidence that high stress levels, leading to high cortisol levels, during pregnancy can lead to a predisposition for the offspring to be of a low birth weight who then go on to develop many of the adverse effects associated with obesity, predominantly the metabolic syndrome later in life.[7] The placenta is the barrier between mother and fetus, preventing the fetus from being overly exposed to high cortisol levels, this protection comes in the form of the enzyme 11 beta hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 which, in humans, converts active cortisol to inactive cortisone. Mothers who are exposed to high stress levels or who are given exogenous steroids override this enzyme barrier resulting in increased exposure of the fetus to glucocorticoids.These offspring have over expression of glucocorticoid receptors in adipose tissue and an impaired response to stress.[7]

Being obese in pregnancy also has a negative effect on the health of the offspring, the prevalence of obesity in pregnancy is increasing,[8] the timing may be critical for the impact on the offspring, whether there is over nutrition during pregnancy or during both pregnancy and lactation.[8]It is suggested that maternal over nutrition directly affects fetal brain development causing altered appetite, adipocyte differentiation and reduced energy expenditure.[8] Converse to the low birth weight, and subsequent ‘catch up growth,’ in children exposed to high glucocorticoid levels, in maternal obesity results in increased birth weight and a predisposition to being obese in childhood.[8]

Studies in people have also show that maternal diet in pregnancy, particularly one which is high in protein and low in carbohydrates, results in an overactive HPA axis and increased cortisol release in response to stress.[9] Interestingly it seems that the negative effects of ‘fetal programming’ is not constrained to the offspring but can also effect the next generation as well, research is currently being undertaken to see whether the next generation (the great grandchildren of the mother who received the original insult) are affected.

Socioeconomic status and obesity

The prevalence of obesity is determined by both an individual’s socioeconomic status and the value of the countries Human development Index?

A positive association is if you have a higher socioeconomic status then you are more likely to be fat.

A negative association is a lower socioeconomic status associated with a larger body size.

Originally looked into by Sobal and Stunkard2 in 1989 and more recently by McLaren 1 published in 2007, was the relationship between proportions of positive and negative associations as one move across countries with a high human development index (HDI) to middle to lower.

McLarens findings were similar to that of Sobal and Stunkards; Countries with a lower HDI had a larger proportion of positive associations than those with higher HDI, whilst the more developed countries with higher HDI values had a larger proportion of negative associations. 1

So we understand that obesity rates vary across the globe and that obesity can result from being both relatively rich or relatively poor but this is which is related to the HDI of the particular country. In simple terms, if you are rich in a poor country you are likely to be obese. If you are poor in a rich country you are likely to be obese.

Why are obesity rates higher amongst those from a lower socioeconomic status than from a more wealthy background in a developed country?

It is widely thought that individuals from higher socioeconomic groups are able to purchase the commonly more expensive yet healthier foodstuffs, such as fruit, vegetables and lower fat milk.

Bourdieu’s concept of “habitus” uses the concept of the body as a social metaphor as a person’s status. A thin and slender body is likely to be more socially valued and materially viable than a fat one. Even within an obesogenic environment these conceptual ideas may help maintain differences between classes for whom thinness is thought of an ideal of physical beauty. ,1

McLaren’s review also touched on location affluence. People that live in an affluent area have heightened pressure to be thin. As well as the local amenities for physical activity and healthy food stuffs.

Why are obesity rates higher amongst those from a high socioeconomic status in a developing country?

It was covered in McLaren’s review, the suggestion by Monteiro that patterns of high energy expenditure among the poor and the cultural values that favour a larger body size, are likely to also contribute to the positive associations seen in low HDI countries. (Mentioned above) ,1

As a country GDP increases, it has been mentioned by Monterio that this causes a shift of obesity towards those with a lower SES.6

Lindsay McLaren. (2007) Socioeconomic Status and Obesity. Epidemiologic Reviews;29: 29–48

Sobal J, Stunkard AJ. (1989) Socioeconomic status and obesity: a review of the literature. Psychol Bull;105:260–75.

Power EM.(2005) Determinants of healthy eating among low-income Canadians. Can J Public Health.;9:S37–8.

Rubinstein S, Caballero B.(2000) Is Miss America an undernourished role model? (Letter). JAMA ;283:1569.

McLaren L, Gauvin L.(2003) Does the ‘average size’ of women in the neighbourhood influence a woman’s likelihood of body dissatisfaction? Health Place. 9:327–35.

Monteiro CA, Moura EC, Conde WL, et al. (2004) Socioeconomic status and obesity in adult populations of developing countries: a review. Bull World Health Organ 82:940–6.

- ↑ Chaput JP et al. (2011) Modern sedentary activities promote overconsumption of food in our current obesogenic environment Obes Rev 12:e12-20 PMID 20576006

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Rutter H (2011) Where next for obesity? Lancet

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Parent-Thirion A (2007) Fourth European working conditions survey. European foundation for the improvement of living and working conditions.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Dallman M et al. (2003) Chronic stress and obesity: a new view of "comfort food PNAS 100: 11696-701

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Pecorano N et al.(2004) Chronic stress promotes palatable feeding which reduces signs of stress: feedforward and feedback effects of chronic stress. Endocrinology 145: 3754-62

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Foss B, Drystad SM (2011) Stress in obesity: cause or consequence? Med Hypotheses 77:7-10.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Seckl J (2004) Prenatal glucocorticoids and long term programming Eur J Endocrinol 151:49-62

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Drake A, Reynolds R (2010) Impact of maternal obesity on offspring obesity and cardiometabolic disease risk Reproduction 140:387-98

- ↑ Reynolds R et al.(2007) Stress responsiveness in adult life: Influence of mother’s diet in late pregnancy J Clin Endocrinol Metabol 92:2208-10