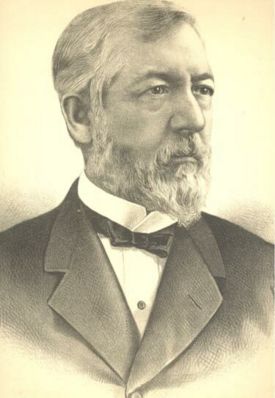

James G. Blaine

James G. Blaine (1830-1893) was a leading American Republican politician and diplomat during the Civil War and Reconstruction eras and the Gilded Age. He was the unsuccessful GOP candidate for president in 1884. He was tainted by scandal, but created an innovative foreign policy.

Blaine was born in West Brownsville, Pa., Jan. 31, 1830, moving in 1841 with his parents to Washington, Pa. He graduated from Washington and Jefferson College in 1847 and studied law. Blaine taught school, first in slaveholding Kentucky (1848-1852) and then in Philadelphia (1852-1854). In 1854 he moved to his wife's home in Augusta, Maine, and purchased an interest in the Republican newspaper the Kennebec Journal. He entered politics as a Republican, was elected to the state legislature in 1858, and was twice reelected, serving as speaker in 1861 and 1862. From 1859 to 1881 he was chairman of the Republican State Committee in Maine. Blaine was a fluent writer and a master at political management, In 1862 he was elected to Congress, where he took the lead in financial legislation. He never served in uniform. He held the powertful position of Speaker the House from 1869 to 1875, during Reconstruction. On July 10, 1876, he was appointed to fill a vacancy in the United States Senate, and later was elected to the six-year term, serving until 1881.

Blaine was a magnetic speaker in an era of oratory, a man of charisma. As a moderate Republican he supported President Abraham Lincoln during the Civil War. As a major leader during Reconstruction he took an independent course in his advocacy of black suffrage, but opposed the coercive measures of the Radical Republicans during the administration of Ulysses S. Grant. He opposed a general amnesty bill, secured the confidence and support of the Grand Army of the Republic, worked for a reduction in the tariff and generally sought and obtained strong support from the Western states. Railroad promotion and construction were important in this period, and as a result of his interest and support Blaine was charged with graft and corruption in the awarding of railroad charters. The proof or falsity of the charges was supposed to rest in the so-called "Mulligan letters," which Blaine refused to release to the public, but from which he read in his successful defense in the House. He proposed the Blaine Amendment in 1875, an amendment to the federal Constitution that would forbid the public funding of private, denominational schools. It passed the House but failed in the Senate and never became federal law, but 30 states copied it into their state constitutions.

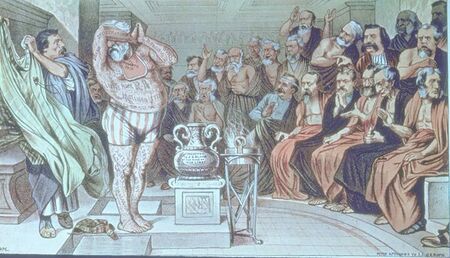

Blaine was a leading candidate going into the 1876 Republican National Convention; he was nominated by Robert G. Ingersoll in a brilliant speech that made Ingersoll famous, extolling him as the "Plumed Knight:"

- The people demand a man whose political reputation is spotless as a star; but they do not demand that their candidate shall have a certificate of moral character signed by a Confederate congress. . . . This is a grand year--a year filled with recollections of the Revolution. . . a year in which the people call for the man who has torn from the throat of treason the tongue of slander--for the man who has snatched the mask of Democracy from the hideous face of rebellion; for the man who, like an intellectual athlete, has stood in the arena of debate and challenged all comers, and who is still a total stranger to defeat.... James G. Blaine marched down the halls of the American Congress and threw his shining lance full and fair against the brazen foreheads of the defamers of his country and the maligners of his honor.

The rivalries between Blaine's "Half Breeds" and Stalwarts (Grant supporters) was so strong that a compromise candidate, Rutherford B. Hayes of Ohio, was chosen and then elected in a highly controversial election that ended Reconstruction.

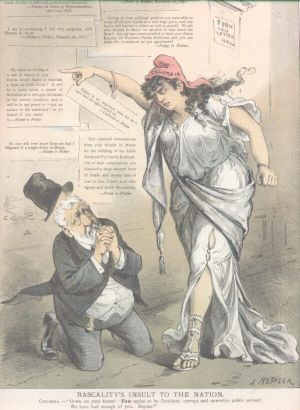

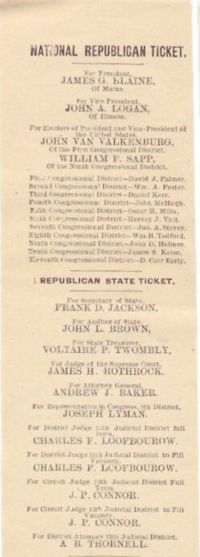

Blaine was again the leading candidate in 1880; but the same bitter factionalism defeated him once more. His ally James A. Garfield was nominated and elected, and Blaine was appointed Secretary of State. Garfield was soon assassinated and after a few months Blaine left the cabinet. Finally in 1884 he was nominated on the first ballot, with General John A. Logan of Illinois as his running mate. Blaine's opponent was Grover Cleveland, a Bourbon Democrat who, as governor of New York, was a leader in political reform, particularly of the civil service. The election was very close but Blaine could not shake the corruption allegations. Mugwumps, led by prominent Republican reformers, switched to Cleveland. Late in the campaign came an indiscreet remark of one of his supporters, the Reverend S. D. Burchard, who ridiculed the Democratic opposition as the party of "rum, Romanism, and rebellion." (That is, saloons, Catholics and ex-Confederates.) It was an insult especially to Irish Catholics, a Democratic constituency Blaine was courting. Blaine won only 182 out of a total of 401 electoral votes, but Cleveland's popular vote margin was less than 25,000 in a total of more than 10,000,000.

Still the party leader, Blaine resumed his writing and speaking, and visited Europe. He helped Benjamin Harrison become the GOP nominee in 1888; in 1889 President Harrison appointed Blaine his Secretary of State. During three years of service in this office, probably the most constructive part of his career, Blaine's focused on relations with Latin-American and Britain. He pushed for an canal across Panama, built, operated, and controlled by the United States; he secured Congressional legislation resulting in the Pan-American Conference which met in Washington in October, 1889. Blaine's set up the Bureau of American Republics in Washington.[1] As an early environmentalist he used diplomacy to protect the seal herds in the Pribilof Islands of Alaska.[2] He tried to annex Hawaii (which almost succeeded in early 1893, but was postponed to 1898). Indeed, the permanent influence of Blaine on American life was through his foreign policy. Although Blaine concluded tariff reciprocity agreements with eight Latin American nations, reciprocity negotiations with Canada stalled in 1891-92. Harrison and Blaine feared a political backlash from American farmers and lumbermen if concessions were made to Canada. Blaine's Anglophobia also influenced the outcome of the negotiations, and Canada's negotiators to the end resisted the inclusion of reciprocity on manufactured articles in any treaty.[3] The two most important reciprocity agreenents were signed with Brazil and with Spain for Cuba and Puerto Rico.

Though not a candidate in 1892, Blaine received nearly 200 votes on the first ballot. After the election Blaine's health failed rapidly, and he died in Washington, on Jan. 27, 1893.

In foreign policy Blaine was a transitional figure, marking the end of one era in foreign policy and foreshadowing the next. [4] He brought energy, imagination and verve to the office in sharp contrast with his somnolent rivals, inspiring his activist twentieth-century successors. He was a pioneer in arbitration treaties, tariff reciprocity, and American administration of Latin American customs houses. to avert civil wars over the revenue stream. Blaine wanted the the U.S. to be the protector and leader of the Western Hemisphere, even if the Latin America countries disagreed. He insisted on keeping the Americas away from European control while favoring peaceful arbitration and negotiations rather than war. Blaine forcefully argued for the national interests of his country. He kept the big picture firmly in mind, seeking long-term programs and not simply short-term fixes for the matter at hand.

References

- ↑ Healy (2001)

- ↑ Charles S. Campbell, Jr., "The Anglo-American Crisis in the Bering Sea, 1890-1891." Mississippi Valley Historical Review 1961 48(3): 393-414. Issn: 0161-391x Fulltext: in Jstor

- ↑ Allan B. Spetter, "Harrison and Blaine: No Reciprocity for Canada." Canadian Review of American Studies 1981 12(2): 143-156. Issn: 0007-7720

- ↑ Healy (2001) p 253