John Dalton

|

Note: Text in font-color Blue link to articles in Citizendium; text in font-color Maroon link to articles not yet started; |

John Dalton (1766-1844), an English scientist, one of the founders of modern chemistry — through his quantitative formulation of an atomic theory — and a pioneer founder of modern meteorology, taught mathematics and physical sciences at New College, Manchester, resigning his position in favor of lecturing, private tutoring and research, having begun his teaching career at the age of 12 years as founder and teacher of an elementary school in his local community.[1] [2] [3]

Dalton inferred from experimental studies of the atmosphere, and other researches on gases, liquids and solids, an atomic theory of matter, the ancient Greeks having first suggested the idea, Robert Boyle and Issac Newton having accepted it without evidence, Dalton, early on thinking atomisticly, providing its experimental support, establishing that all elements did not have the same mass and size, a finding that not only contributed to the development of his atomic theory but also led to the proof of the law of definite proportions, hinted at but little understood by chemists before Dalton.

He developed experimental methods for determining the relative weights of the atoms of different elements, he formulated the law of partial pressures (Dalton's law) — "....where the pressure exerted by each gas in a mixture [of gases] is independent of the pressure exerted by the other gases, and where the total pressure is the sum of the pressures of each gas."[4] — and he formulated a law about the combining of elements into compounds, the law of multiple proportions, which only makes sense in the light of Dalton's atomic theory.

|

In the vestibule of the Manchester Town Hall are placed two life-sized marble statues facing each other. One of these is that of John Dalton, by Chantrey; the other that of James Prescott Joule, by Gilbert. Thus honour is done to Manchester's two greatest sons - to Dalton, the founder of modern Chemistry and of the Atomic Theory, and the discoverer of the laws of chemical-combining proportions; to Joule, the founder of modern Physics and the discoverer of the law of the Conservation of Energy. The one gave to the world the final and satisfactory proof of the great principle, long surmised and often dwelt upon, that in every kind of chemical change no loss of matter occurs; the other proved that in all the varied modes of physical change no loss of energy takes place. Dalton, by determining the relative weights of the atoms which take part in chemical change, proved that every such change - whether from visible to invisible, from solid to liquid, or from liquid to gas - can be represented quantitatively by a chemical equation; and he created the Atomic Theory of Chemistry by which these changes are explained. Joule, by exact experiment, proved the truth of the same statement for the different forms of energy. —Sir Henry Roscoe, John Dalton and the Rise of Modern Chemistry. 1895. [1] |

Dalton suffered from color-blindness and studied that affliction, which later physicians referred to as Daltonism.

Dalton's law of multiple proportions

Dalton's law of multiple proportions: If two elements — elements Y and Z, say — can form multiple different compounds, the ratio of the weights of any one element in the different compounds — element Z, say — when it combines with a fixed weight of another — element Y, say — will compute as ratios of small integral (whole) numbers — viz., Z:Y = 2:1 or 3:1 or 3:2, etc.

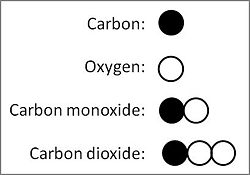

Using modern values for the atomic masses of elements, the existence of the two compounds of carbon (C) and oxygen (O), carbon monoxide (CO) and carbon dioxide (C02), offers a simple example to illustrate the law of multiple proportions. Carbon, the element of fixed mass in the two compounds, which today chemists take as having an atomic mass of 12, combines with two different masses of oxygen, namely 16 (atomic mass of oxygen) in carbon monoxide, 32 (sum of atomic mass of two oxygen atoms) in carbon dioxide. Those two masses of oxygen in the two compounds with a fixed mass of carbon relate to each other in the ratio 16-to-32, which equals 1-to-2, a ratio of two whole small numbers. Dalton would have determined the actual weights in grams of oxygen in the two compounds, adjusting them to a fixed weight of carbon, and calculated the ratio of oxygen in the two compounds therefrom. Thus, empirically observed, 10 grams of carbon combines with 13.3 grams of oxygen to form carbon monoxide, and 26.6 grams of oxygen to form carbon dioxide, the ratio 13.3:26.6 = 1:2 for oxygen in the two compounds.

For another example, consider the elements nitrogen, N, and oxygen O. The element oxygen occurs in the compounds NO (nitric oxide) and NO2 (nitric dioxide). The ratio of oxygen weights (1:2) in those compounds contains the small whole numbers 1 and 2.

Note that in modern chemistry the concept "number of atoms" replaces "weight", used by Dalton. Now chemists say that the ratio of numbers of O-atoms in different NOx compounds (or in different N2Ox compounds) is expressible as a ratio of small whole numbers.[5]

Bernard Jaffe, in his popular book on the history of chemistry, Crucibles, The Story of Chemistry: From Ancient Alchemy to Nuclear Fission, describes the history of the law of multiple proportions:

While working on the relative weights of the atoms, Dalton noticed a curious mathematical simplicity. Carbon united with oxygen in the ratio of 3 [parts by weight] to 4 [parts by weight] to form carbon monoxide, that poisonous gas which is used as a fuel in the gas-range. Carbon also united with oxygen to form gaseous carbon dioxide in the ratio of 3 [parts by weight] to 8 [parts by weight]. Why not 3 to 6, or 3 to 7? Why that number 8 which was a perfect multiple of 4 [a ratio of 2-to-1]? If that were the only example, Dalton would not have bothered his head. But he found a more striking instance among the oxides of nitrogen, which Cavendish and Davy had investigated. Here the same amount of nitrogen united with one, two and four parts of oxygen to form three distinct compounds. Why these numbers which again were multiples of each other? He had studied two other gases, ethylene and methane, and found that methane contained exactly twice as much hydrogen as ethylene. Why this mathematical simplicity? [6]

Thinking atomistically, Dalton literally figured out the answer, using the figures, or symbols, he had invented for an atom of each of the known elements: (see accompanying illustration.)

If, as Dalton's atomic theory proposed, elements consisted of atoms differing in weight among elements but of equal weights for the atoms of a given element, and compounds consisted of atoms of different elements, then when a fixed bulk weight of one element combined to form different compounds with another element, the ratio of the bulk weights of that other element in the different compounds must relate as ratios of small whole numbers, as those bulk weights reflect the accumulated weight of the atoms of that other element in single particles of the compounds, which themselves relate as ratios of small whole numbers.

Jaffe reports that the Swedish chemist, Jöns Jacob Berzelius (1779-1848), a contemporary of Dalton, stated Dalton´s explanation as:

In a series of compounds made up of the same elements, a simple ratio exists between the weights of one and the fixed weight of the other element.

And in a letter to Dalton, Berzelius wrote:

….this Law of Multiple Proportions was a mystery without the atomic hypothesis.[6]

By extension of Dalton's law of multiple proportions, the subscripts m, n, k, ... in a compound AmBnCk⋅⋅⋅ are integral numbers (integers). In other words, the law applies to the ratio of the differing elements in a given compound as well as the ratio of the same element in differing compounds.

The law of multiple proportions may helped lead Dalton to his theory that an element consists of atoms of the same weight and that the weights atoms of different elements differ, inasmuch as when the weights of element O, say, when it forms different compounds with a fixed weight of element N, say, the differing weights of O in the differing compounds relate as the ratio small whole numbers. It also helped lay the foundation for writing formulas for chemical compounds. Nevertheless, exactly how Dalton arrived at his theory of chemical atoms has many differing scenarios by historians of chemistry, and the true scenario may not proceed through any logical, ordered sequence.[7]

Dalton assigned the mass of the lightest element, hydrogen, 1, as the unit of atomic mass, enabling him to determine the relative atomic weights of different elements — relative to the unit weight of hydrogen.

The law of multiple proprtions upholds the validity of the theory of matter's nature as comprising atoms of different masses, and therefore of different shapes and sizes. Nevertheless, as philospher of science, Maureen Christie, points out, one cannot understand the law of multiple proportions as a universal and unexceptioned law of nature, such as the law of conservation of energy. She notes that one cannot express the law of multiple proportions as a precise proposition owing to the use of such imprecise words as 'small' and 'simple' in its expression:

The law of multiple proportions as understood by chemists, includes ‘simple’ as an essential descriptor of the whole number ratios. The law therefore cannot be formulated as a precise proposition. It is clearly instanced, and exactly instanced, but it also has clear exceptions, and there are cases where it cannot be decided how the law applies....The hydrocarbons provide a series of examples of the difficulty: there are thousands of different compounds which contain just the two elements carbon and hydrogen. If a comparison is made between ethyne (acetylene - C2H2) and ethene (ethylene - C2H4), the law of definite proportions is very simply and obviously instanced. A sample of ethene containing the same mass of carbon as a sample of ethyne always has just exactly twice as much hydrogen as the ethyne, but if we compare pentane (C5H12) with ethyne, the ratio is 12:5 rather than the simpler 2:l. We could go on to compare heptane (C7H16)with butane (C4H10), obtaining a ratio of 35:32, or even C25H52 with C33H8, which gives 429:425! [footnote]. It can be seen that although the first comparison is in the ratio of simple whole numbers, the large range of compounds provides many comparisons which can be chosen to give ratios of almost any desired complexity. Certainly the last comparison could not fairly be regarded as providing an analysis in the ratio of simple [or small] whole numbers at all.[8]

For further reading regarding 'laws' in chemistry, see:[9]

Early life

Aerial map of England showing relative locations of Eaglesfield (red circle), Dalton´s birthplace (b. 1766), Kendall (yellow star), where he taught school (1781-1793), and Manchester (green star), where he taught physical sciences and mathematics (1793-1799), before resigning to pursue private research, earning a living lecturing and private tutoring. Image courtesy of the U.S. National Air and Space Administration (NASA), through Window Live Search. See: [Original map.]

John Dalton entered the world in a thatch-roofed cottage in the village of Eaglesfield in England's northwest coastal county of Cumberland, on September 5 or 6, 1766, of Quaker parents Joseph and Deborah, his father a hand-loom weaver. He early showed intellectual promise and perseverance in learning. He had competent and inspirational schoolmasters, including an instrument-maker and meteorologist, Elihu Robinson, who gave him much attention. According to English chemist, H.E. Roscoe, who first isolated the element, vanadium, Dalton wrote of his early years in a letter dated 1832:

|

The writer of this was born at Eaglesfield, near Cockermouth, Cumberland. Attended the village schools there, and in the neighbourhood, till eleven years of age, at which period he had gone through a course of mensuration, surveying, navigation, etc. [1] |

More to come....

References and notes cited in text

|

Many citations to articles listed here include links to full-text — in font-color blue. Accessing full-text may require personal or institutional subscription to the source. Nevertheless, many do offer free full-text, and if not, usually offer text or links that show the abstracts of the articles. Links to books variously may open to full-text, or to the publishers' description of the book with or without downloadable selected chapters, reviews, and table of contents. Books with links to Google Books often offer extensive previews of the books' text. |

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Roscoe HE. (1895) John Dalton and the Rise of Modern Chemistry. New York: Macmillan & Co.

- ↑ John Dalton. Free full-text article from Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ↑ Millington JP. (1906) John Dalton. E.P. Dutton & Co.: New York. Free full-text of book by former scholar of Christ's College, Cambridge.

- ↑ John Dalton. Chemical Achievers Website.

- ↑ Eight molecular manipulable models of different compounds of solely nitrogen and oxygen, illustrating the law of multiple proportions. USC Department of Chemistry.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Jaffe B. (1976) Crucibles, The Story of Chemistry: From Ancient Alchemy to Nuclear Fission. 4th Edition. Dover Publications, Inc: New York. ISBN 0-4S6-2J342•j. Full-Text of Chapter VII, Dalton: A Quaker Builds the Smallest of Worlds.

- ↑ Rocke AJ. (1984) Chemical Atomism in the Nineteenth Century: From Dalton to Cannizzaro. Ohio State University Press: Columbus. ISBN 0814203604. 386 pages.

- About the Author: Alan J. Rocke appears to have devoted his life to the academic study and teaching of the history of chemistry, having received a Ph.D. in the History of Science in 1975 at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, climbed the academic ladder at Case Western Reserve University, culminating in appointment as Henry Eldrige Bourne Professor of History in 1995. His many awards include the Dexter Award for Outstanding Contributions to the History of Chemistry in 2000. His publications include numerous books and refereed articles on numerous aspects of the history of chemistry. See: http://www.cwru.edu/artsci/hsty/rocke-cv.pdf, http://www.scs.uiuc.edu/~mainzv/HIST/awards/Dexter%20Papers/RockeDexterBioJJB.pdf, and Alan J. Rocke's Website.

- ↑ Christie M. (1994) Philosophers versus chemists concerning the 'laws of nature'. Stud. Hist. Phil. Sci. 25(4):613-629.

- ↑ Christie M, Christie JR. (2000) "Laws" and "Theories" in Chemistry Do Not Obey the Rules. In: Of Minds and Molecules: New Philosophical Perspectives on Chemistry. Nalini Bhushan, Stuart M. Rosenfeld (editors). Oxford University Press US, ISBN 0195128346, ISBN 9780195128345.