Mind-body problem

The mind-body problem is the philosophical and scientific consideration of the relation between conscious mental activity such as judgment, volition, and emotion and the underlying physical plant that supports this activity, consisting primarily of the brain (seen as a complex of neurons, synapses and their dynamic interactions), but also involving various sensors throughout the body, most notably the eye, ear, mouth, and nose.

A distinction is often made in the philosophy of mind between the mind and the brain, and there is some controversy as to their exact relationship. Narrowly defined, the brain is defined as the physical and biological matter contained within the skull, responsible for all electrochemical neuronal processes. More broadly defined, the brain includes the dynamical activity of the brain, as studied in neuroscience. The mind, however, is seen in terms of mental attributes, such as consciousness, will, beliefs or desires. Some imagine that the mind exists independently of the brain, and some believe in a soul, or other epiphenomena. In the field of artificial intelligence, or AI, so called strong AI theorists, say that the mind is separate from the brain in the same way that a computer algorithm exists independent of its many possible realizations in coding and physical implementation, and the brain and its 'wiring' is analogous to a computer and its software.[1]

The brain

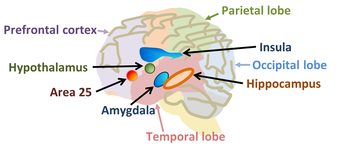

Some human brain areas; some of the labeled areas are buried inside the brain. Area 25 refers to Brodmann's area 25, a region implicated in long-term depression.

The brain is hugely complex, with perhaps as many as 10,000 different types of neuron, each with different intrinsic properties that use many different signalling systems. Altogether in the human brain there are several billion neurons, each making perhaps 10,000 synaptic connections - but as well as communication by synapses these neurons also intercommunicate by autocrine, paracrine, and neurohormonal chemical signals. Neuroscientists believe that neurons and the(mainly) chemical signals that pass between them are the fundamental units of information in the brain, that these signals interact with the intrinsic properties of individual neurones to generate patterns of electrical activity within those neurons, and that these patterns in turn determine what chemical messengers are made and when they are released. Experience alters the patterns and strengths of connectivity between neurons, and neuroscientists believe that this is the basis of learning.

Mind

Neuroscientists have found that some patterns of neural network activities correlate with some mental states, and have identified regions of the brain that participate in various personality disorders, mood disorders, addictions, and dementias, such as Alzheimer's disease. The figure shows a sampling of the many known human brain areas. Brodmann labeled many more. Brodmann's area 25 located deep in the frontal lobe is implicated in long-term depression. The prefrontal cortex is involved in decision making, judgment, planning for the future. The amygdala is involved in emotion. The hippocampus is involved in memory. The insula is involved in bodily somatic sensations; it receives and interprets sensory information from organs in the joints, ligaments, muscles, and skin. The hypothalamus is involved in appetite and drive. It should be noted, however, that the activities of these regions are not entirely localized, but are coupled by the brain's circuitry, not in a static, fixed manner, but in an ever-changing dynamic manner.

Conventionally, neuroscientists assume that consciousness ("self awareness") is an emergent property of computer-like activities in the brain's neural networks, a view called connectionism. In massively complex systems like the brain, complexity can give rise to unexpected higher order activities, so-called emergent properties, not easily foreseen from the properties of individual neurones, but related to their cooperative behavior. Such emergent properties are very difficult to work with and understand, precisely because they arise unpredictably in highly complex systems. Nevertheless, an important part of contemporary neuroscience is the understanding of neuronal networks and the relations between network behaviour and the behaviour of single cells, and to study how higher order behaviors emerge from the properties of the component units from which networks are built.

Dualism

Interest in the mind-body problem has a history going back many millenia, with some of the early writing credited to the Stoics who believed in fate determining the course of events, and yet felt one must as a matter of being human, think through one's choices.[2] This division has been re-invented over and over again in various forms of dualism,[3] encompassing various attempts to answer the question "What makes us who we are?",[4] one issue being the interpretation of the experience of conscious intention or free will.

These issues may be viewed as an empirical matter, something to be settled by careful observation, and indeed a great deal has been learned about the mechanisms of various mental phenomena such as emotion, addiction, psychological conditioning and so forth. But a fundamental stumbling block to the empirical program is that mental states are introspected and the best an empirical approach can do is to establish correlations between subjective mental states and observable brain activity. These observations are echoed by experimentalists studying brain function:[5]

|

"...it is important to be clear about exactly what experience one wants one's subjects to introspect. Of course, explaining to subjects exactly what the experimenter wants them to experience can bring its own problems–...instructions to attend to a particular internally generated experience can easily alter both the timing and he content of that experience and even whether or not it is consciously experienced at all." Susan Pockett, The neuroscience of movement[5] |

A more epistemological description is provided by Nothoff of the Institute of Mental Health Research: [6]

|

"Epistemically, the mind is determined by mental states, which are accessible in First-Person Perspective. In contrast, the brain, as characterized by neuronal states, can be accessed in Third-Person Perspective. The Third-Person Perspective focuses on other persons and thus on the neuronal states of others' brain while excluding the own brain. In contrast, the First-Person Perspective could potentially provide epistemic access to own brain...However, the First-Person Perspective provides access only to the own mental states but not to the own brain and its neuronal states." Georg Northoff, Philosophy of the Brain: The Brain Problem, p. 5[6] |

These observations suggest the possibility that phenomena of consciousness and neurology inhabit different realms, and it is confusion to try to explain introspected experiences using a neurological approach that by its very nature excludes the effects of observation upon what is observed. As Niels Bohr would have it, descriptions of conscious states like intention are in a complementary relation to empirical observation:

|

"For instance, it is impossible, from our standpoint, to attach an unambiguous meaning to the view sometimes expressed that the probability of the occurrence of certain atomic processes in the body might be under the direct influence of the will. In fact, according to the generalized interpretation of the psycho-physical parallelism, the freedom of the will is to be considered as a feature of conscious life which corresponds to functions of the organism that not only evade a causal mechanical description but resist even a physical analysis carried to the extent required for an unambiguous application of the statistical laws of atomic mechanics. Without entering into metaphysical speculations, I may perhaps add that an analysis of the very concept of explanation would, naturally, begin and end with a renunciation as to explaining our own conscious activity."... |

| "...On the contrary, the recognition of the limitation of mechanical concepts in atomic physics would rather seem suited to conciliate the apparently contrasting viewpoints of physiology and psychology. Indeed, the necessity of considering the interaction between the measuring instruments and the object under investigation in atomic mechanics exhibits a close analogy to the peculiar difficulties in psychological analysis arising from the fact that the mental content is invariably altered when the attention is concentrated on any special feature of it." –Niels Bohr, Light and Life[7] |

These cautionary remarks are not endorsed universally, and many believe an empirical approach can succeed, although such answers still elude us. One such school of thought proposes that a better understanding of how complex systems (like the brain) involving feedback mechanisms that as yet defy analysis[8] ultimately will show mental states are related to cooperative actions of neurons and synapses analogous to emergent phenomena seen in many other complex systems. Along these lines, Freeman introduces the replacement of "causality" by what he calls "circular causality" to "allow for the contribution of self-organizing dynamics", the "formation of macroscopic population dynamics that shapes the patterns of activity of the contributing individuals", applicable to "interactions between neurons and neural masses...and between the behaving animal and its environment"[9]

References

- ↑ John R Searle (1997). John Haugeland, ed: Mind Design II: Philosophy, Psychology, and Artificial Intelligence, 2nd ed. MIT Press, p. 203. ISBN 0262082594.

- ↑ Chrysippus (279 – 206 BC) attempted to reconcile the inner with the outer worlds by suggesting the mind ran under different rules than the outer world. See for example, Keimpe Algra (1999). “Chapter VI: The Chyrsippean notion of fate: soft determinism”, The Cambridge History of Hellenistic Philosophy. Cambridge University Press, p. 529. ISBN 0521250285.

- ↑ Robinson, Howard (Nov 3, 2011). Edward N. Zalta ed:Dualism. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2011 Edition).

- ↑ Joseph E. LeDoux (2003). “Chapter 1: The big one”, Synaptic Self: How Our Brains Become Who We Are. Penguin Books, p. 1 ff. ISBN 0142001783.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Susan Pockett (2009). “The neuroscience of movement”, Susan Pockett, WP Banks, Shaun Gallagher, eds: Does Consciousness Cause Behavior?. MIT Press, p. 19. ISBN 0262512572.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 A rather extended discussion is provided in Georg Northoff (2004). Philosophy of the Brain: The Brain Problem, Volume 52 of Advances in Consciousness Research. John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 1588114171.

- ↑ Niels Bohr (April 1, 1933). "Light and Life". Nature: p. 457 ff. Full text on line at us.archive.org.

- ↑ J. A. Scott Kelso (1995). Dynamic Patterns: The Self-Organization of Brain and Behavior. MIT Press, p. 16. ISBN 0262611317. “An order parameter is created by the correlation between the parts, but in turn influences the behavior of the parts. This is what we mean by circular causality.” Kelso also says (p. 9): "But add a few more parts interlaced together and very quickly it becomes impossible to treat the system in terms of feedback circuits. In such complex systems, ... the concept of feedback is inadequate.[...] there is no reference state with which feedback can be compared and no place where comparison operations are performed."

- ↑ Walter J Freeman (2009). “Consciousness, intentionality and causality”, Susan Pockett, WP Banks, Shaun Gallagher, eds: Does Consciousness Cause Behavior?. MIT Press, p. 88. ISBN 0262512572.