Superfund

The Superfund refers to a perennially underfunded U.S. federal trust fund for cleanup of toxic waste dumps. The program was established in 1980[1] and is administered by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The superfund's actual name (used by environmental professionals) is the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980, frequently shorted to the acronym CERCLA. Money for the superfund originally came from an excise tax on petroleum and chemical manufacturers, but the tax expired in 1995, and since 2001, the burden of the cost shifted to taxpayers.

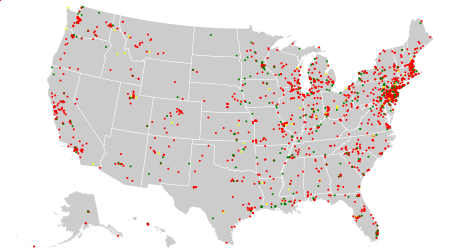

Of all the sites selected for possible action under this program (and there are tens of thousands across the U.S.), 1178 (as of 2024) remain on the National Priorities List (NPL)[2] that makes them eligible for cleanup under the Superfund program.[3] The priority sites are highly contaminated and need to undergo longer-term remedial investigation and cleanup. The state of New Jersey, the fifth smallest state in the U.S., is the location of about ten percent of the priority Superfund sites, a disproportionate amount.

The Superfund never had enough money to clean up all the priority sites. By 2014, cleanup activity had dwindled to only 8 sites. In November 2021, Congress reauthorized an excise tax on chemical manufacturers which should help bolster Superfund action.

The EPA seeks to identify parties responsible for the pollution needing cleanup. If the responsible parties can be found, the EPA may either compel them to clean up the sites or it may undertake the cleanup on its own using Superfund moneys and seek to recover those costs from the responsible parties through settlements or other legal means.

Approximately 70% of Superfund cleanup activities historically have been paid for by the potentially responsible parties (PRPs)[4]. In other cases, the responsible party either could be found or was unable to pay for the cleanup. In these circumstances, taxpayers have been paying for the cleanup operations.

The Superfund law also authorizes federal natural resource agencies (primarily the EPA), states, and Native American tribes to recover natural resource damages caused by hazardous substances, though most states have and most often use their own versions of a state Superfund law. The law also created the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR).

The primary goal of a Superfund cleanup is to reduce the risks to human health through a combination of cleanup, engineered controls like caps, and site restrictions such as groundwater use restrictions. A secondary goal is to return the site to productive use as a business, recreation, or natural ecosystem. Identifying the intended reuse early in the cleanup often results in faster and less expensive cleanups. EPA's Superfund Redevelopment Program provides tools and support for site redevelopment.[5]

History

The Superfund was created by Congress in 1980 in response to the threat of hazardous waste sites, typified by the Love Canal disaster in New York, and the Valley of the Drums in Kentucky.[6] It was recognized that funding would be difficult, since the responsible parties were not easily found, and so the Superfund was established to provide funding through a taxing mechanism on certain industries and to create a comprehensive liability framework to be able to hold a broader range of parties responsible.[4] The initial Superfund trust fund to clean up sites where a polluter could not be identified, could not or would not pay (bankruptcy or refusal), consisted of about $1.6 billion[7] and then increased to $8.5 billion.[4] Initially, the framework for implementing the program came from the oil and hazardous substances National Contingency Plan.

The EPA published the first Hazard Ranking System in 1981, and the first National Priorities List in 1983.[8] Implementation of the program in early years, during the Ronald Reagan administration, was ineffective, with only 16 of the 799 Superfund sites cleaned up and only $40 million of $700 million in recoverable funds from responsible parties collected.[9] The mismanagement of the program under Anne Gorsuch Burford, Reagan's first chosen Administrator of the agency, led to a congressional investigation and the reauthorization of the program in 1986 through an act amending the Superfund law.[10]

1986 amendments

The Superfund Amendments and Reauthorization Act of 1986 (SARA) added minimum cleanup requirements in Section 121, and required that most cleanup agreements with polluters be entered in federal court as a consent decree subject to public comment (section 122).[11] This was to address sweetheart deals between industry and the Reagan-era EPA that Congress had discovered.[12][13]

Environmental justice initiative

In 1994 President Bill Clinton issued Executive Order 12898, which called for federal agencies to make achieving environmental justice a requirement by addressing low income populations and minority populations that have experienced disproportionate adverse health and environmental effects as a result of their programs, policies, and activities.[14] The EPA regional offices had to apply required guidelines for its Superfund managers to take into consideration data analysis, managed public participation, and economic opportunity when considering the geography of toxic waste site remediation.[15] Some environmentalists and industry lobbyists saw the Clinton administration’s environmental justice policy as an improvement, but the order did not receive bipartisan support. The newly elected Republican Congress made numerous unsuccessful efforts to significantly weaken the program. The Clinton administration then adopted some industry favored reforms as policy and blocked most major changes.[16]

Decline of excise tax

Until the mid-1990s, most of the funding came from an excise tax on the petroleum and chemical industries, reflecting the polluter pays principle.[17] Even though by 1995 the Superfund balance had decreased to about $4 billion, Congress chose not to reauthorize collection of the tax, and by 2003 the fund was empty.[18]1 Since 2001, most of the funding for cleanups of hazardous waste sites has come from taxpayers. State governments pay 10 percent of cleanup costs in general, and at least 50 percent of cleanup costs if the state operated the facility responsible for contamination. By 2013 federal funding for the program had decreased from $2 billion in 1999 to less than $1.1 billion (in constant dollars).[17]11

In 2001 EPA used funds from the Superfund program to institute the cleanup of anthrax on Capitol Hill after the 2001 Anthrax Attacks.[19] It was the first time the agency dealt with a biological release rather than a chemical or oil spill.

From 2000 to 2015, Congress allocated about $1.26 billion of general revenue to the Superfund program each year. Consequently, less than half the number of sites were cleaned up from 2001 to 2008, compared to before. The decrease continued during the Obama Administration, and since under the direction of EPA Administrator Gina McCarthy Superfund cleanups decreased even more from 20 in 2009 to a mere 8 in 2014.[7]8

Reauthorization of excise tax

In November 2021 Congress reauthorized an excise tax on chemical manufacturers, under the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.[20] The new chemical excise tax is effective July 1, 2022 and is double the rate of the previous Superfund tax. The 2021 law also authorized $3.5 billion in emergency appropriations from the U.S. government general fund for hazardous site cleanups in the immediate future.[21]

Provisions

The Superfund law authorizes two kinds of response actions:

- Removal actions. These are typically short-term response actions, where actions may be taken to address releases or threatened releases requiring prompt response. Removal actions are classified as: (1) emergency; (2) time-critical; and (3) non-time critical. Removal responses are generally used to address localized risks such as abandoned drums containing hazardous substances, and contaminated surface soils posing acute risks to human health or the environment.[22]

- Remedial actions. These are usually long-term response actions. Remedial actions seek to permanently and significantly reduce the risks associated with releases or threats of releases of hazardous substances, and are generally larger, more expensive actions. They can include measures such as using containment to prevent pollutants from migrating, and combinations of removing, treating, or neutralizing toxic substances. These actions can be conducted with federal funding only at sites listed on the EPA National Priorities List (NPL) in the United States and the territories. Remedial action by responsible parties under consent decrees or unilateral administrative orders with EPA oversight may be performed at both NPL and non-NPL sites, commonly called Superfund Alternative Sites in published EPA guidance and policy documents.[23]

A potentially responsible party (PRP) is a possible polluter who may eventually be held liable under the Superfund law for the contamination or misuse of a particular property or resource. Four classes of PRPs may be liable for contamination at a Superfund site:

- the current owner or operator of the site;[24]

- the owner or operator of a site at the time that disposal of a hazardous substance, pollutant or contaminant occurred;[25]

- a person who arranged for the disposal of a hazardous substance, pollutant or contaminant at a site;[26] and

- a person who transported a hazardous substance, pollutant or contaminant to a site, who also has selected that site for the disposal of the hazardous substances, pollutants or contaminants.[27]

The liability scheme of the Superfund law changed commercial and industrial real estate, making sellers liable for contamination from past activities, meaning they can’t pass liability onto unknowing buyers without any responsibility. Buyers also have to be aware of future liabilities.[4]

The Superfund law also required the revision of the National Oil and Hazardous Substances Pollution Contingency Plan 9605(a)(NCP).[28] The NCP guides how to respond to releases and threatened releases of hazardous substances, pollutants, or contaminants. The NCP established the National Priorities List, which appears as Appendix B to the NCP, and serves as EPA´s information and management tool. The NPL is updated periodically by federal rulemaking.[29]

The identification of a site for the National Priorities List (NPL) is intended primarily to guide the EPA in:

- Determining which sites warrant further investigation to assess the nature and extent of risks to human health and the environment

- Identifying what CERCLA-financed remedial actions may be appropriate

- Notifying the public of sites the EPA believes warrant further investigation

- Notifying PRPs that the EPA may initiate CERCLA-financed remedial action.[29]

Including a site on the NPL does not itself require PRPs to initiate action to clean up the site, nor assign liability to any person. The NPL serves informational purposes, notifying the government and the public of those sites or releases that appear to warrant remedial actions.Template:Citation needed

The key difference between the authority to address hazardous substances and pollutants or contaminants is that the cleanup of pollutants or contaminants, which are not hazardous substances, cannot be compelled by unilateral administrative order.Template:Citation needed

Despite the name, the Superfund trust fund has lacked sufficient funds to clean up even a small number of the sites on the NPL. As a result, the EPA typically negotiates consent orders with PRPs to study sites and develop cleanup alternatives, subject to EPA oversight and approval of all such activities. The EPA then issues a Proposed Plans for remedial action for a site on which it takes public comment, after which it makes a cleanup decision in a Record of Decision (ROD). RODs are typically implemented under consent decrees by PRPs or under unilateral orders if consent cannot be reached.[30] If a party fails to comply with such an order, it may be fined up to $37,500 for each day that non-compliance continues. A party that spends money to clean up a site may sue other PRPs in a contribution action under the CERCLA.[31] CERCLA liability has generally been judicially established as joint and several among PRPs to the government for cleanup costs (i.e., each PRP is hypothetically responsible for all costs subject to contribution), but CERCLA liability is allocable among PRPs in contribution based on comparative fault. An "orphan share" is the share of costs at a Superfund site that is attributable to a PRP that is either unidentifiable or insolvent.[32] The EPA tries to treat all PRPs equitably and fairly. Budgetary cuts and constraints can make more equitable treatment of PRPs more difficult.Template:Citation needed[33]

Procedures

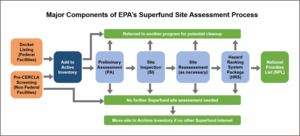

Upon notification of a potentially hazardous waste site, the EPA conducts a Preliminary Assessment/Site Inspection (PA/SI), which involves records reviews, interviews, visual inspections, and limited field sampling.[34] Information from the PA/SI is used by the EPA to develop a Hazard Ranking System (HRS) score to determine the CERCLA status of the site. Sites that score high enough to be listed typically proceed to a Remedial Investigation/Feasibility Study (RI/FS).[35]

The RI includes an extensive sampling program and risk assessment that defines the nature and extent of the site contamination and risks. The FS is used to develop and evaluate various remediation alternatives. The preferred alternative is presented in a Proposed Plan for public review and comment, followed by a selected alternative in a ROD. The site then enters into a Remedial Design phase and then the Remedial Action phase. Many sites include long-term monitoring. Once the Remedial Action has been completed, reviews are required every five years, whenever hazardous substances are left onsite above levels safe for unrestricted use.

- The CERCLA information system (CERCLIS) is a database maintained by the EPA and the states that lists sites where releases may have occurred, must be addressed, or have been addressed. CERCLIS consists of three inventories: the CERCLIS Removal Inventory, the CERCLIS Remedial Inventory, and the CERCLIS Enforcement Inventory.[32]

- The Superfund Innovative Technology Evaluation (SITE) program supports development of technologies for assessing and treating waste at Superfund sites. The EPA evaluates the technology and provides an assessment of its potential for future use in Superfund remediation actions. The SITE program consists of four related components: the Demonstration Program, the Emerging Technologies Program, the Monitoring and Measurement Technologies Program, and Technology Transfer activities.[32]

- A reportable quantity (RQ) is the minimum quantity of a hazardous substance which, if released, must be reported.[32][36]

- A source control action represents the construction or installation and start-up of those actions necessary to prevent the continued release of hazardous substances (primarily from a source on top of or within the ground, or in buildings or other structures) into the environment.[32][37]

- A section 104(e) letter is a request by the government for information about a site. It may include general notice to a potentially responsible party that CERCLA-related action may be undertaken at a site for which the recipient may be responsible.[38] This section also authorizes the EPA to enter facilities and obtain information relating to PRPs, hazardous substances releases, and liability, and to order access for CERCLA activities.[39] The 104(e) letter information-gathering resembles written interrogatories in civil litigation.[39]

- A section 106 order is a unilateral administrative order issued by EPA to PRP(s) to perform remedial actions at a Superfund site when the EPA determines there may be an imminent and substantial endangerment to the public health or welfare or the environment because of an actual or threatened release of a hazardous substance from a facility, subject to treble damages and daily fines if the order is not obeyed.[32]

- A remedial response is a long-term action that stops or substantially reduces a release of a hazardous substance that could affect public health or the environment. The term remediation, or cleanup, is sometimes used interchangeably with the terms remedial action, removal action, response action, remedy, or corrective action.[32]

- A nonbinding allocation of responsibility (NBAR) is a device, established in the Superfund Amendments and Reauthorization Act, that allows the EPA to make a nonbinding estimate of the proportional share that each of the various responsible parties at a Superfund site should pay toward the costs of cleanup.[32][40]Template:Unreliable source?

- Relevant and appropriate requirements are those United States federal or state cleanup requirements that, while not "applicable," address problems sufficiently similar to those encountered at the CERCLA site that their use is appropriate. Requirements may be relevant and appropriate if they would be "applicable" except for jurisdictional restrictions associated with the requirement.[32][37]

Implementation

Template:As of, there were 1,322 sites listed; an additional 447 had been delisted, and 51 new sites have been proposed.

Historically about 70 percent of Superfund cleanup activities have been paid for by potentially responsible party (PRPs). When the party either cannot be found or is unable to pay for the cleanup, the Superfund law originally paid for site cleanups through an excise tax on petroleum and chemical manufacturers. The chemical and petroleum taxes were intended to provide incentives to use less toxic substances.Template:Citation needed Over five years, $1.6 billion was collected, and the tax went to a trust fund for cleaning up abandoned or uncontrolled hazardous waste sites.Template:Citation needed

The last full fiscal year (FY) in which the Department of the Treasury collected the excise tax was 1995.[18]1 At the end of FY 1996, the invested trust fund balance was $6.0 billion. This fund was exhausted by the end of FY 2003. Since that time Superfund sites for which the PRPs could not pay have been paid for from the general fund.[18]1, 3 Under the 2021 authorization by Congress, collection of excise taxes from chemical manufacturers will resume in 2022.[21]

Hazard Ranking System

The Hazard Ranking System is a scoring system used to evaluate potential relative risks to public health and the environment from releases or threatened releases of hazardous wastes at uncontrolled waste sites. Under the Superfund program, the EPA and state agencies use the HRS to calculate a site score (ranging from 0 to 100) based on the actual or potential release of hazardous substances from a site through air, surface water or groundwater. A score of 28.5 places the site on the National Priorities List, making the site eligible for long-term remedial action (i.e., cleanup) under the Superfund program.[32]

Environmental discrimination

Template:More citations needed section

Federal actions to address the disproportionate health and environmental disparities that minority and low-income populations face through Executive Order 12898 required federal agencies to make environmental justice central to their programs and policies.[41] Superfund sites have been shown to impact minority communities the most.[42] Despite legislation specifically designed to ensure equity in Superfund listing, marginalized populations still experience a lesser chance of successful listing and cleanup than areas with higher income levels. After the executive order had been put in place, there persisted a discrepancy between the demographics of the communities living near toxic waste sites and their listing as Superfund sites, which would otherwise grant them federally funded cleanup projects. Communities with both increased minority and low-income populations were found to have lowered their chances of site listing after the executive order, while on the other hand, increases in income led to greater chances of site listing.[43] Of the populations living within 1 mile radius of a Superfund site, 44% of those are minorities despite only being around 37% of the nation's population.

As of January 2021, more than 9,000 federally-subsidized properties, including ones with hundreds of dwellings, were less than a mile from a Superfund site.[44]

Case studies in African American communities

In 1978, residents of the rural black community of Triana, Alabama were found to be contaminated with DDT and PCB, some of whom had the highest levels of DDT ever recorded in human history.[45] The DDT was found in high levels in Indian Creek, which many residents relied on for sustenance fishing. Although this major health threat to residents of Triana was discovered in 1978, the federal government did not act until 5 years later after the mayor of Triana filed a class-action lawsuit in 1980.

In West Dallas, Texas, a mostly African American and Latino community, a lead smelter poisoned the surrounding neighborhood, elementary school, and day care facilities for more than five decades. Dallas city officials were informed in 1972 that children in the proximity of the smelter were being exposed to lead contamination. The city sued the lead smelters in 1974, then reduced its lead regulations in 1976. It wasn't until 1981 that the EPA commissioned a study on the lead contamination in this neighborhood, and found the same results that had been found a decade earlier. In 1983, the surrounding day cares had to close due to the lead exposure while the lead smelter remained operating. It was later revealed that EPA Deputy Administrator John Hernandez had deliberately stalled the cleanup of the lead-contaminated hot spots. It wasn't until 1993 that the site was declared a Superfund site, and at the time it was one of the largest ones. However, it was not until 2004 when the EPA completed the cleanup efforts and eliminated the lead pollutant sources from the site.

The Afton community of Warren County, North Carolina is one of the most prominent environmental injustice cases and is often pointed to as the roots of the environmental justice movement. PCB's were illegally dumped into the community and then it eventually became a PCB landfill. Community leaders pressed the state for the site to be cleaned up for an entire decade until it was finally detoxified.[46] However, this decontamination did not return the site to its pre-1982 conditions. There has been a call for reparations to the community which has not yet been met.

Bayview-Hunters Point, San Francisco, a historically African American community, has faced persistent environmental discrimination due to the poor remediation efforts of the San Francisco Naval Shipyard, a federally declared Superfund site.[47] The negligence of multiple agencies to adequately clean this site has led Bayview residents to be subject to high rates of pollution and has been tied to high rates of cancer, asthma, and overall higher health hazards than other regions of San Francisco.[48][49]

Case studies in Native American communities

Template:Unreferenced section One example is the Church Rock uranium mill spill on the Navajo Nation. It was the largest radioactive spill in the US, but received a long delay in government response and cleanup after being placed as a lower priority site. Two sets of five-year clean up plans have been put in place by US Congress, but contamination from the Church Rock incident has still not been completely cleaned up. Today, uranium contamination from mining during the Cold War era remains throughout the Navajo Nation, posing health risks to the Navajo community.

Accessing data

The data in the Superfund Program are available to the public.

- Superfund Site Search[50]

- Superfund Policy, Reports and Other Documents[51]

- TOXMAP was a Geographic Information System (GIS) from the Division of Specialized Information Services[52] of the United States National Library of Medicine (NLM) that was deprecated on December 16, 2019. The application used maps of the United States to help users visually explore data from the EPA Toxics Release Inventory (TRI) and Superfund programs. TOXMAP was a resource funded by the US Federal Government. TOXMAP's chemical and environmental health information is taken from NLM's Toxicology Data Network (TOXNET),[53] PubMed, and other authoritative sources.

Future challenges

While the simple and relatively easy sites have been cleaned up, EPA is now addressing a residual number of difficult and massive sites such as large-area mining and sediment sites, which is tying up a significant amount of funding. Also, while the federal government has reserved funding for cleanup of federal facility sites, this clean-up is going much more slowly. The delay is due to a number of reasons, including EPA’s limited ability to require performance, difficulty of dealing with Department of Energy radioactive wastes, and the sheer number of federal facility sites.[4]

Attribution

- Some content on this page may previously have appeared on Wikipedia.

References

- ↑ Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA) and Federal Facilities and its amendments on EPA.gov

- ↑ The EPA and state agencies use the Hazard Ranking System (HRS) to calculate a site score (ranging from 0 to 100) based on the actual or potential release of hazardous substances from a site. A score of 28.5 places a site on the National Priorities List, eligible for cleanup under the Superfund program.

- ↑ Superfund: National Priorities List (NPL) on the website of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Thomas Voltaggio and John Adams. “Superfund: A Half Century of Progress.” EPA Alumni Association. March 2016.

- ↑ Superfund Redevelopment Program (2021-12-08).

- ↑ Superfund: 20th Anniversary Report: A Series of Firsts. EPA.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Kaley Beins and Stephen Lester. Superfund Polluters Pay So Children Can Play. 35th Anniversary Report. December 2015, 80 pp, The Center for Health, Environment & Justice

- ↑ Superfund History. EPA (May 15, 2017).

- ↑ Not So Super Superfund, The New York Times, February 7, 1994.

- ↑ An Interview with Lee Thomas, EPA’s 6th Administrator. Video, Transcript (see p12). April 19, 2012.

- ↑ Superfund: SARA Overview. EPA.

- ↑ (1985) "Negotiation and Informal Agency Action: The Case of Superfund". Duke Law Journal 1985 (2): 276–7. DOI:10.2307/1372358. Research Blogging. “From 1981 until mid-1983, the Superfund program suffered from frequent policy shifts and reorganizations, patent abuse by its leadership, and a demoralizing slowdown of Fund expenditures and other cleanup initiatives. Negotiation acquired a bad name during this period because key officials appeared willing to negotiate unduly generous cleanup terms with site users.”

- ↑ Weisskopf, Michael. Toxic-Waste Site Awash in Misjudgment, 1986-11-16.

- ↑ (2015) Failed Promises: The Federal Government's Response to Environmental Inequality. MIT Press, 29, 56. DOI:10.7551/mitpress/9780262028837.001.0001. ISBN 9780262028837.

- ↑ (2004) "Neoliberalism and Environmental Justice in the United States Environmental Protection Agency: Translating Policy into Managerial Practice in Hazardous Waste Remediation". Geoforum 35 (3): 285–297. DOI:10.1016/j.geoforum.2003.11.003. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Cushman, John H. Jr.. Congress forgoes its bid to hasten cleanup of dumps, The New York Times, October 6, 1994.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Template:Cite report

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Superfund Program: Updated Appropriation and Expenditure Data. GAO (February 18, 2004).

- ↑ "The Anthrax Cleanup of Capitol Hill." Documentary by Xin Wang produced by the EPA Alumni Association. Video, Transcript (see p 3, 4). May 12, 2015.

- ↑ United States. Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. Template:USPL Section 80201. Approved November 15, 2021.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Template:Cite report

- ↑ Code of Federal Regulations, Template:CodeFedReg.

- ↑ Template:CodeFedReg.

- ↑ CERCLA section 107(a)(1)

- ↑ CERCLA 107(a)(2)

- ↑ CERCLA 107(a)(3)

- ↑ CERCLA 107(a)(4); Template:USC.

- ↑ Template:CodeFedReg.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Basic NPL Information. EPA (2021-02-09).

- ↑ CERCLA sections 104, 106, 122 Template:USC.

- ↑ CERCLA, Template:USC.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 32.4 32.5 32.6 32.7 32.8 32.9 Template:Cite report

- ↑ FY 2016 EPA Budget in Brief. EPA.

- ↑ Superfund Site Assessment Process. EPA (2021-02-05).

- ↑ Hazard Ranking System. EPA (2022-03-22).

- ↑ CERCLA and EPCRA Continuous Release Reporting. EPA (2021-12-08).

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 EPA. "Part 300—National Oil and Hazardous Substances Pollution Contingency Plan; Definitions." Code of Federal Regulations, 40 CFR 300.5

- ↑ CERCLA, Template:USCSub. "Information Gathering and Access."

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 (2002) CERCLA: Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (Superfund). Chicago: American Bar Association. ISBN 9781590311165.

- ↑ Barbara J. Graves, David Jordan, Dominique Cartron, Daniel B. Stephens, Micheal A. Francis. "Allocating Responsibility for Groundwater Remediation Costs" Experts.com

- ↑ Summary of Executive Order 12898 - Federal Actions to Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations. EPA (2018-09-17).

- ↑ Crawford, Collin (1994). "Strategies for Environmental Justice: Rethinking CERCLA Medical Monitoring Lawsuits". Boston University Law Review 74.

- ↑ O’Neil, Sandra George (2007-07-01). "Superfund: Evaluating the Impact of Executive Order 12898". Environmental Health Perspectives 115 (7): 1087–1093. DOI:10.1289/ehp.9903. ISSN 0091-6765. PMID 17637927. PMC 1913562. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Thousands of U.S. Public Housing Residents Live in the Country's Most Polluted Places (2021-01-13).

- ↑ Bullard, Robert (2012). The Wrong Complexion for Protection: How the Government Response To Disaster Endangers African American Communities. New York: NYU Press, 100–125.

- ↑ (2009) “African Americans on the Front Line”, Health Issues in the Black Community. John Wiley & Sons, 179. ISBN 978-0-47055-266-7.

- ↑ Hunter's Point Shipyard: Ex Workers Say Fraud Rampant at Navy Cleanup, SF Gate, June 29, 2017.

- ↑ Community Call for Environmental Justice for Bayview—Why does the Department of Defense promise to clean up hazardous wastes apply to the Presidio but not to the Hunters Point Naval Shipyard?, SF Gate, April 13, 2000.

- ↑ Hot story; Navy admits burning 600,000 gallons of radioactive fuel at S.F. shipyard, SF Gate, May 21, 2003.

- ↑ Search for Superfund Sites Where You Live. EPA (2021-09-15).

- ↑ Superfund Policy, Reports and Other Documents. EPA (2021-01-06).

- ↑ SIS Specialized Information System. United States National Library of Medicine.

- ↑ Toxnet. United States National Library of Medicine.