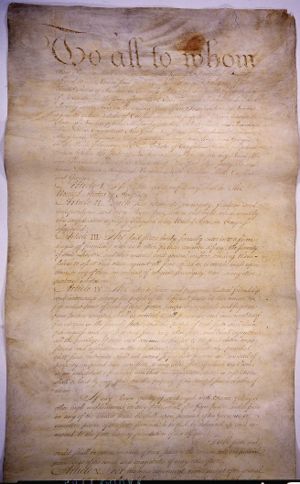

Articles of Confederation

The Articles of Confederation was the first constitution, of the United States of America. The new nation had been formed on July 4, 1776, but its government (called "the United States in Congress assembled") operated until 1781 without a written constitution. The Articles were written in summer 1777 and adopted by the Second Continental Congress on November 15, 1777 after a year of debate. In practice the unratified Articles were used by the members of Congress as the de facto system of government until it became de jure by final ratification on March 1, 1781.[1] The articles created a weak national government that had the power to make war and sign foreign alliances, but lacks a president, a judiciary, and especially the power to raise taxes. Its great achievements were holding the nation together in wartime, and in the 1780s resolving the issues of land ownership in the western territories. By late 1786, three years after the peace, the Articles were in widespread discredit and many national leaders, led by [[George Washington, Alexander Hamilton and James Madison organized to create a wholly new constitution. The Articles operated until early 1789 when they were replaced by the new Constitution of the United States of America, which created a much stronger national government.

Background

The idea of a central government for the 13 main British colonies in America dates to the Albany Congress of 1754. Led by Benjamin Franklin there were discussions about unity for more effective defense against the French and Indians. The Albany Congress drafted a plan that proposed a central government with the power to raise troops and levy taxes for colonial defense, to dispose of western lands and create new colonies, and to regulate Indian affairs. Colonial legislatures rejected the plan and Great Britain ignored it.

After the expulsion of France from North America in 1763, there was no longer an external danger to the colonies. They did not need British military or naval protection. The British, however, insisted on imposing a series of taxes, partly to raise revenue and partly to demonstrate the superiority of Parliament. The Americans insisted that possessed the traditional rights of Englishmen and only their elected officials had the power to raise taxes; they were not represented in Parliament, which therefore could not levy taxes. The dispute was unbridgeable, especially as Americans started adopting republican political ideas that warned the aristocratic British system was corrupt and dangerous. Popular leaders in the colonies, such as Samuel Adams in Massachusetts and Patrick Henry in Virginia tried to achieve united opposition to British policies. The colonies, without British permission, formed first Continental Congress in 1774 to protest British clampdown on Boston. Leaders such as Adams argued that there must be a central government to regulate trade, to prevent civil war among the colonies, and to suppress internal dissension. Nothing was done. When the British attacked at Lexington and Concord in April 1775, a spontaneous uprising broke out. The 'Second Continental Congress assembled in Philadelphia under the name of the "United Colonies." Once the British officials had been expelled from all 13 colonies, they became states and on July 4, 1776, declared independence as a new nation, "The United States of America." Within a few days a draft of articles of confederation was laid before Congress.

National Powers

The Articles set the rules for operations of the United States government. The new nation was capable of making war, negotiating diplomatic agreements, and resolving issues regarding the western territories; it could print money and borrow inside and outside the US. One major weakness was it lacked taxing authority; it had to request funds from the states. A second weakness was one-state, one-vote. The larger states were expected to contribute more but had only one vote. As Benjamin Franklin complained, "Let the smaller Colonies give equal money and men, and then have an equal vote. But if they have an equal vote without bearing equal burdens, a confederation upon such iniquitous principles will never last long."[2] The Articles created a weak national government designed to manage the American Revolution. When the war ended in 1783, its many inadequacies became glaringly obvious, and national leaders such as George Washington and Alexander Hamilton called for a new charter. The Articles were replaced by the much stronger United States Constitution, which was ratified by all 13 states and went into effect with the inauguration of the first President, George Washington, in 1789 in New York City.

Debating the issues

The Articles of Confederation were proposed by a committee headed by John Dickinson on July 12, 1776. The Congress debated the original proposal over the course of meeting during 1777, and finalized the Articles on 15 November, 1777. The main disputes were whether taxes should be apportioned according to the gross number of inhabitants counting slaves or excluding them (the South wanted slaves excluded to lower its taxes; the decision was to use land values as a tax base; whether large and small states should have equality in voting (the decision was one state, one vote); whether Congress should be given the right to regulate Indian affairs (the decision was yes); and whether Congress should be permitted to fix the western boundaries of those states which claimed territory as far west as the Mississippi River. The last issue held up final approval until 1781. The Articles said all costs of the national government were to be defrayed from a common treasury, to which the states were to voluntarily contribute in proportion to the value of their surveyed land and improvements. The states were likewise to supply quotas of soldiers, in proportion to the white inhabitants of each. Congress was given full control over foreign affairs, making war, and of the postal service; it was empowered to borrow money, emit bills of credit, and determine the value of coin; it was to appoint all naval officers and the higher ranking military officers, and control Indian affairs. The states were forbidden to enter into treaties, confederations, or alliances, to meddle with foreign affairs, or to wage war without congressional consent, unless invaded. Most important, they were to give to free inhabitants of other states all the privileges and immunities of their own citizens.

Confederation of sovereign states

The Articles of Confederation created a federal government - a government whereby the member states are sovereign in their own sphere and delegate certain powers to the national government, which was to be a They provided for a "perpetual union." For example, Article 3 of the Articles locks the states into a mutual defense treaty, promising troops from all states to help repel invasion of any state from outside. Article 2, however, makes it clear that the states retain all powers not expressly granted to the national government.

Western lands

In 1776 seven states had overlapping and conflicting claims to western lands that were based on royal grants and charters. Virginia had the largest claim, which included the present states of Kentucky and West Virginia, and parts of Ohio, Indiana and Illinois. Cutting across Virginia's northwestern claims were the claims of Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New York. South of Virginia were the claims of North Carolina (claiming Tennessee) and South Carolina and Georgia, which claimed the lands between their western boundaries and the Mississippi. The ownership of such vast areas by a few states aroused jealousy and ill-feeling among the six smaller states that had no western lands. Maryland refused to ratify the Articles until the landowning states surrendered their claims to the new government.

The Continental Congress successfully urged the states to cede their land claims to it and promised that the territory so ceded would be erected into new states having full equality with the old. New York and Virginia ceded their claims in 1781 and 1783. Virginia ceded its lands in Ohio on condition of being allowed to reserve for itself the Military District between the Scioto and Little Miami rivers to satisfy military grants made during the Revolution. Virginia also retained its land south of the Ohio, which became the state of Kentucky in 1791. In 1785 Massachusetts ceded its claim to a belt of land extending across the present states of Michigan and Wisconsin, and in the following year Connecticut ceded its western lands. Connecticut reserved to itself a tract of 3.8 million acres in northeastern Ohio--called the Western Reserve--a part of which was set aside for the relief of Connecticut sufferers whose property had been destroyed by the British during the Revolution. The remainder was sold to the Connecticut Land Company. South Carolina ceded its narrow strip of land in 1787, and North Carolina transferred its western lands in 1790. All the land in Kentucky and Tennessee had already been granted to revolutionary war veterans, settlers, and land companies so the Confederation received no land but only political jurisdiction.

These cessions of 222 million acres of western lands gave to the national government a vast public domain in which it owned the land and over which it had governmental jurisdiction. In 1785 a land ordinance provided a method of selling the lands. In 1787, in response to demands of the Ohio and Scioto land companies, which were negotiating for the purchase of large tracts of land north of the Ohio, the Northwest Ordinance was adopted to provide a form of government for what came to be known as the "Old Northwest." The Ordnance, written by Thomas Jefferson, provided for an elaborate survey that created the checkerboard land pattern still in use, and provided that no slavery was allowed there during the territorial stage.[3]

State support

Why did the states give up some of their sovereignty to create a new nation, During the Revolution it was obvious that unity was needed to overcome a much stronger British Empire and to collaborate with allies like France. Dougherty (2001) uses analytic techniques borrowed from economics that are together known to political scientists as "positive theory," and concludes that after peace was achieved in 1783 the states had no apparent reason for cooperation. Indeed they started laying import tariffs on each others’ goods. The national government had to beg the states for money; but during the war the states were strapped for funds. They could not tax imports because their ports were blockaded. The old tax system operated but generated only a small stream of revenue, so new moneys were raised by seizing and selling royal property and the assets of loyalists who fled the state.[4] The states were never able to comply 100% with national levies and requisitions; but they did provided 53% of the men levied for the Continental army from 1777 to 1783 and 40% of the money requisitioned for the federal treasury from 1782 to 1789.

The American leaders state, national and local were dedicated to a new common republican ideology that made the common good a core value. The states had different rates of voluntary contribution to the national government at different times, depending on circumstances. In the case of troop levies, Dougherty shows that the closer a state was to British military threats, the higher its contribution to the national defense. The rate was in direct proportion to how threatening the British were, As the battlegrounds moved southward, the compliance of southern states rose accordingly and that of northern states fell off. In peacetime, 1782 to 1789, Dougherty reports that voluntary monetary payments increased in proportion to the level of domestic debt held by citizens of each state. Paying money to the national government in order to pay down the war debt thus benefited a state to the extent that its own citizens would be repaid.[5]

Text

Article 1

Article 1 of the Articles of Confederation confirms the name of the new nation as "The United States of America." The name forst appeared in the Declaration of Independence, which created the nation.

Article 2

Article 2 affirms that each state is a sovereign and independent state and retains all powers not granted to the Congress.

Article 3

Article 3 affirms a "league of friendship," and binds all states into a common defense pact.

Article 4

Article 4 ensures that when a citizen of one state travels in or through another state, the person shall enjoy all the rights of the citizens of the state he or she is traveling through. It also ensures free travel between the states. It requires a state to hand over a fugitive from justice who has fled to that state. Finally, it requires that full faith and credit by given to the records and acts of one state by all other states.

Most of the provisions of Article 4 were carried over into the Constitution in its Article 4

Article 5

Article 5 of the Articles of Confederation establishes the Congress, a unicameral legislature known officially as the "The United States in Congress Assembled". Each state legislature chose its congressional delegates and was free to send from two to seven members. Delegates had a term limit of no more than three years every six years. When a vote came to the floor of the Congress, each state's delegates would meet to determine the state's vote - states voted as states, individual members of Congress did not vote as individuals.

Article 5 guarantees freedom of speech in the Congress, and provides immunity to all members of Congress for whatever is spoken in Congress. Additionally, Article 5 provides that all members of Congress be free from arrest while traveling to and from Congress.

Article 6

Article 6 of the Articles of Confederation places limits on the states. Specifically:

- no state can enter into a treaty without the consent of Congress

- no state can grant a title of nobility (nor shall Congress)

- no vessels of war may be kept in peacetime, except that number determined by Congress necessary for defense

- no state may engage in a war except on the authorization of Congress, unless invaded or in danger of invasion

Article 7

Article 7 of the Articles of Confederation ensures that all military officers of the state militias, at the rank of colonel or below, will be appointed by the state legislature.

Article 8

Article 8 of the Articles of Confederation directs that any expenses of the United States will be paid out of a common treasury, with deposits made to the treasury by the states in proportion to the value of the land and buildings in the state.

The inability of the Congress to force the states to pay this levy was one of the major weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation.

Article 9

Article 9 of the Articles of Confederation lists the powers of the Congress. For example:

- the power to declare war and peace

- the power to send and receive ambassadors

- the power to make treaties

- the power to grant letters of marque

- the power to regulate the currency of the Unites States and the individual states

- the power to fix standards and measures

- the power to establish post offices

- the power to make rules for land and naval forces

- the power to borrow money on the behalf of the United States

- the power to build and equip a navy

- the power to determine the size of an army and to requisition troops from each state to fill the need

- the power to arm, equip, and clothe the members of the army

Article 9 also makes Congress the final court of appeal for disputes between states. All decisions of the Congress must be made by majority vote of the states.

Additionally, Article 9 establishes "A Committee of the States," which takes the place of the full Congress when it is not in session. This committee is made up of one member of Congress from each state.

Article 9 also directed Congress to choose one of its number to be presiding officer (to be chosen for one year, and with a service limit of one year out of three). This person, often referred to as "President," had a role much akin to the Speaker of the House of the House of Representatives under the Constitution.

The Congress must meet at least once a year, and may adjourn at any time, though never for more than six months at a time. Article 9 requires Congress publish its proceedings and the results of all votes taken.

Article 10

Article 10 of the Articles of Confederation allows the Committee of the States, or any nine individual states, to make decisions for the United States when Congress is in adjournment.

Article 11

Article 11 of the Articles of Confederation invites Canada to join the United States as a new state, at any time. Other new states, however, must be approved by the vote of nine existing states.

Article 12

Article 12 of the Articles of Confederation ensures that all debt incurred by the Continental Congresses assembled before the Articles goes into effect will be valid and binding on the United States.

Article 13

Article 13 of the Articles of Confederation requires the states to be held to the decisions of Congress; it notes that the union is perpetual; and that any changes to the Articles must be agreed upon by Congress and all states.

Signers

The signers were:[6]

Connecticut

Delaware

- Thomas McKean 02/12/1779

- John Dickinson 05/05/1779

- Nicholas Van Dyke

Georgia

- John Walton 07/24/1778

- Edward Telfair

- Edward Langworthy

Maryland

- John Hanson 03/01/1781

- Daniel Carroll

Massachusetts

New Hampshire

- Josiah Bartlett

- John Wentworth Jr. 08/08/1778

New Jersey

- John Witherspoon 11/26/1778

- Nathaniel Scudder 11/26/1778

New York

North Carolina

- John Penn 07/21/1778

- Cornelius Harnett

- John Williams

Pennsylvania

Rhode Island

South Carolina

Virginia

Replacement

The Articles were in effect until the the Constitution was ratified and the first Congress met in 1789.

Presiding Officers of the Congress

Notably, the Articles of Confederation did not create an executive nor a national judiciary. Aside from Congress's role as final judge of disputes between states, all judicial powers remained with the states. The Committee of the States held a quasi-executive role, in that it could make decisions for the nation when the Congress was not in session. The Articles also created the office of Presiding Officer of the United States in Congress Assembled.

This office was often shortened and referred to as "President," though the "President of the United States in Congress Assembled" under the Articles was a minor figure compared to the "President of the United States of American" under the Constitution. The men elected to the office of Presiding Officer of Congress were:

- Samuel Huntington (03/02/1781 - 07/06/1781)

- Thomas McKean (07/07/1781 - 11/04/1781)

- John Hanson (11/05/1781 - 11/03/1782)

- Elias Boudinot (11/04/1782 - 11/02/1783)

- Thomas Mifflin (11/03/1783 - 11/29/1784)

- Richard Henry Lee (11/30/1784 - 11/22/1785)

- John Hancock (11/23/1785 - 06/05/1786)

- Nathaniel Gorham (06/06/1786 - 02/01/1787)

- Arthur St. Clair (02/02/1787 - 01/21/1788)

- Cyrus Griffin (01/22/1788 - 04/30/1789)

Note: Huntington was the presiding officer of the Continental Congress when the Articles were finally ratified. He resigned due to ill health and McKean was selected to replace him. Hanson was the first person specifically selected to be the presiding officer of the United States in Congress Assembled.

Notes

- ↑ At that point Congress became the "Congress of the Confederation."

- ↑ July 30, 1776, quoted in Andrew C. McLaughlin, A Constitutional History of the United States (1935) ch 12 note 8

- ↑ Benjamin Horace Hibbard, History of the Public Land Policies (1965)

- ↑ Allan Nevins, The American States during and after the Revolution, 1775-1789 1927

- ↑ See Keith L. Dougherty, Collective Action under the Articles of Confederation. 2001. 225 pp and also Donald S. Lutz, "Why Federalism?" William and Mary Quarterly 2004 61(3): 582-588.

- ↑ When there is no date listed for the signing, the date of signing was 9 July, 1778.