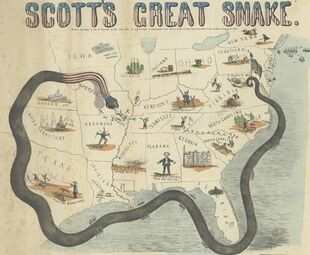

Union Blockade

The Union Blockade was the closing of Confederate ports 1861-1865, during the American Civil War by the Union Navy. The U.S. Navy maintained a massive effort on the Atlantic and Gulf coasts of the Confederate States of America designed to prevent the local and international movement of cotton, supplies, soldiers and arms into or out of the Confederacy. The vast majority of vessels from other nationas obeyed the blockade. However, specialty ships were built to slip through, called blockade runners. They were mostly newly built, high-speed ships with small cargo capacity. They were built and financed by British interests and operated by the British (using Royal Navy officers on leave) and ran between Confederate-controlled ports and the neutral ports of Havana, Cuba (Spanish); Nassau, Bahamas (British) and Bermuda (British), where British suppliers had set up supply bases.

President Abraham Lincoln proclaimed the blockade on April 19, 1861. His strategy, part of the Anaconda Plan of General Winfield Scott, required the closure of 3,500 miles (5,600 km) of Confederate coastline and twelve major ports, including New Orleans, Louisiana, and Mobile, Alabama, the top two cotton-exporting ports, as well as the Atlantic ports of Charleston, South Carolina, Savannah, Georgia, and Wilmington, North Carolina.[1] The Navy department built 500 ships, which destroyed or captured about 1,500 blockade runners over the course of the war. At first five out of six attempts to slip through the blockade were successful; by 1864 only half were successful (which mean the life expectancy of a blockade runner was one round trip). The blockade runners carried only a small fraction of the usual cargo. Thus, Confederate cotton exports were reduced 95% from 10 million bales in the three years prior to the war to just 500,000 bales during the blockade period.

Proclamation of blockade and legal implications

On April 19, 1861, President Lincoln issued a Proclamation of Blockade Against Southern Ports

- "Whereas an insurrection against the Government of the United States has broken out in the States of South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Florida, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas, and the laws of the United States for the collection of the revenue cannot be effectually executed therein comformably to that provision of the Constitution which requires duties to be uniform throughout the United States...,Now, therefore, I, Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States...have further deemed it advisable to set on foot a blockade of the ports within the States aforesaid, in pursuance of the laws of the United States, and of the law of Nations, in such case provided. For this purpose a competent force will be posted so as to prevent entrance and exit of vessels from the ports aforesaid. If, therefore, with a view to violate such blockade, a vessel shall approach, or shall attempt to leave either of the said ports, she will be duly warned by the Commander of one of the blockading vessels, who will endorse on her register the fact and date of such warning, and if the same vessel shall again attempt to enter or leave the blockaded port, she will be captured and sent to the nearest convenient port, for such proceedings against her and her cargo as prize, as may be deemed advisable.

Recognition of the Confederacy

Lincoln was sharply criticized by Congress for not simply closing the ports. [2] Under international law and maritime law, however, nations had the right to search neutral vessels on the open sea if they were suspected of violating a blockade, something port closures would not allow. In an effort to avoid conflict between the United States and Britain over the searching of British merchant vessels thought to be trading with the Confederacy, the Union needed the privileges of international law that came with the declaration of a blockade.

Under the Declaration of Paris, 1856, international law required that a blockade must be (1) formally proclaimed, (2) promptly established, (3) enforced, and (4) effective, in order to be legal.[3]

However, by effectively declaring the Confederate States of America to be "belligerents"—rather than insurrectionists, who under international law would not be legally eligible for recognition by foreign powers—Lincoln opened the way for European powers such as Britain and France to recognize the Confederacy. Britain's proclamation of neutrality was consistent with the position of the Lincoln Administration under international law—the Confederates were belligerents—giving them the right to obtain loans and buy arms from neutral powers, and giving the British the formal right to discuss openly which side, if any, to support.[4]

Operations

In May 1861, Secretary of the Navy Gideon Wells appointed a "Blockade Board" to assess the Union's naval blockade of the South. Naval captain Samuel F. Du Pont chaired the board, which included Alexander D. Bache, head of the US Coast Survey; Charles Henry Davis, an astronomer associated with the navy; and Major John G. Barnard, a US Army engineer with expertise in coastal defenses. They published ten reports that detailed such strategic suggestions as dividing the Atlantic Blockading Squadron into two parts and capturing two Atlantic and Gulf Coast locations for coaling and supply stations. Many of their recommendations were implemented and remained in effect for the duration of the Civil War. The board's urged the navy to enable federal troops around the Confederate periphery to stab into the interior, threaten railroads, and play a major role in bisecting the country along the Mississippi River. As a result, expeditionary forces were sent to occupy Hatteras Inlet, North Carolina; Port Royal, South Carolina; Fernandina, Florida; and Ship Island off the coast of Mississippi. The fear of a seaborne force was a powerful threat to the Confederacy.

In the initial phase of the blockade, Union forces concentrated on the Atlantic Coast. The November 1861 capture of Port Royal in South Carolina provided the Federals with an open ocean port and repair and maintenance facilities in good operating condition. It became an early base of operations for further expansion of the blockade along the Atlantic coastline[5]. Apalachicola, Florida, received Confederate goods traveling down the Chattahoochee River from Columbus, Georgia, and was an early target of Union blockade efforts on Florida's Gulf Coast.[6] Another early prize was Ship Island, which gave the Navy a base from which to patrol the entrances to both the Mississippi River and Mobile Bay. The Navy gradually extended its reach throughout the Gulf of Mexico to the Texas coastline, including Galveston and Sabine Pass.[7]

At the start of the war the United States Navy—with a strength of only 90 vessels, of which half were sailing ships—was grossly inadequate for the task at hand, but the Navy Department quickly attempted to correct this deficiency. In 1861, nearly 80 steamers and 60 sailing ships were brought into service, and the number of blockading vessels rose to 160.[8]

To implement its ambitious plan, the Navy grew by the end of 1861 to 24,000 officers and enlisted men, over 15,000 more than in antebellum service, and four squadrons of ships were deployed, two in the Atlantic and two in the Gulf of Mexico.[9]

The Union Army's control of the port of Beaufort, North Carolina, during the Civil War made the navy's blockade of the port of Wilmington, North Carolina, much more effective. Beaufort served as an efficient supply depot for the ships involved in the blockade; coal for Union vessels was shipped and stored there, and naval stores from the Carolinas were shipped north from Beaufort. The port was also used for repairs to vessels and as a launching point for attacks on Fort Fisher, the stubbornly defended Confederate earthen fort at the entrance to the harbor at Wilmington.[10]

Blockade service

Blockade service was attractive to Federal seamen and landsmen alike. Blockade station service was the most boring job in the war but also the most attractive in terms of potential financial gain. The task was for the fleet to sail back and forth to intercept any blockade runners. More than 50,000 men volunteered for the boring duty, because food and living conditions on ship were much better than the infantry offered, the work was safer, and especially because of the real (albeit small) chance for big money. Captured ships and their cargoes were sold at auction and the proceeds split among the sailors. When the USS Aeolus seized the hapless blockade runner Hope off Wilmington, North Carolina, in late 1864, the captain won $13,000, the chief engineer $6,700, the seamen more than $1,000 each, and the cabin boy $533, rather better than infantry pay of $13 per month. The amount garnered for blockade runners widely varied. While the little Alligator sold for only $50, bagging the Memphis brought in $510,000 (about what 40 civilian workers could earn in a lifetime of work). In four years, $25 million in prize money was awarded.

Blockade runners

The type of ship most likely to evade the naval cordon was a small, light ship with a short draft—qualities that facilitated blockade running but were poorly suited to carrying large amounts of heavy weaponry, machinery and other supplies badly needed by the South. For example, it was impossible to import a train engine by blockade. To be successful in helping the Confederacy, a blockade runner had to make many round trips, evading capture every time; eventually most were captured or sank.

Ordinary ships were too slow and visible to escape the Navy. The blockade runners therefore relied mainly on new ships built in England with low profiles, shallow draft, and high speed. Their paddle-wheels, driven by steam engines that burned smokeless anthracite coal, could make 17 knots (31 km/hr). Because the South lacked sufficient sailors, skippers and shipbuilding capability, the runners were built, officered and manned by Brits. Private British investors spent perhaps £50 million on the runners ($250 million in U.S. dollars, equivalent to about $2.5 billion in 2006 dollars). The pay was high: a Royal Navy officer on leave might earn several thousand dollars (in gold) in salary and bonus per round trip, with ordinary seamen earning several hundred dollars. On dark nights they ran the gauntlet to and from the British islands of Bermuda and the Bahamas, or Havana, Cuba, 500-700 miles (800-1,100 km) away. The ships carried several hundred tons of compact, high-value cargo such as cotton, turpentine or tobacco outbound, and rifles, medicine, brandy, lingerie and coffee inbound. They charged from $300 to $1,000 per ton of cargo brought in; two round trips a month would generate perhaps $250,000 in revenue (and $80,000 in wages and expenses).

In November 1864, a wholesaler in Wilmington asked his agent in the Bahamas to stop sending so much chloroform and instead send "essence of cognac" because that perfume would sell "quite high." Confederate patriots held "Rhett Butler" types[11] and the other nouveau riche blockade runners in contempt for profiteering on luxuries while Robert E. Lee's soldiers were in rags. On the other hand, their bravery and initiative were necessary for the nation's survival, and many women in the back country flaunted imported $10 gew gaws and $50 hats as patriotic proof that the "damn yankees" had failed to isolate them from the outer world. The government in Richmond eventually regulated the traffic, requiring half the imports to be munitions; it even purchased and operated some runners on its own account and made sure they loaded vital war goods. By 1864, Lee's soldiers were eating imported meat. The blockade was especially effective in shutting down the delivery of quinine and other medicines to the Confederate medical department. Blockade running was reasonably safe for both sides. It was not illegal under international law; captured foreign sailors were released, while Confederates went to prison camps. The ships were unarmed (cannon would slow them down), so they posed no danger to the Navy warships.

One example of the lucrative (and short-lived) nature of the blockade running trade was the ship Banshee, which operated out of Nassau and Bermuda. She was captured on her seventh run into Wilmington, North Carolina, and confiscated by the U.S. Navy for use as a blockading ship. However, at the time of her capture, she had turned a 700% profit for her English owners, who quickly commissioned and built the Banshee No. 2, which soon joined the firm's fleet of blockade runners.[12]

Impact on the Confederacy

The Union blockade was a powerful weapon that eventually ruined the Southern economy, at the cost of very few lives. The blockade severely reduced cotton exports and choked off munitions imports. The measure of the blockade's success was not the few ships that slipped through, but the thousands that never tried it. Ordinary freighters stopped calling at Southern ports. The interdiction of coastal traffic meant that long-distance travel depended on the rickety railroad system, which never overcame the devastating impact of the blockade. The blockade caused other hardships as well, especially the maldistribution of food. Throughout the war, the South produced enough food for civilians and soldiers, but it had growing difficulty in moving surpluses to areas of scarcity and famine. Lee's army, at the end of the supply line, nearly always was short of supplies as the war progressed into its final two years.

Bread riots in Richmond and other cities showed that patriotism was not sufficient to satisfy the demands of housewives. Land routes remained open for cattle drovers, but after the Federals seized control of the Mississippi River in summer 1863, it became impossible to ship horses, cattle and swine from Texas and Arkansas to the eastern Confederacy. The blockade was a triumph of the U.S. Navy and a major factor in winning the war.

Confederate response

The Confederacy constructed torpedo boats, generally small, fast steam launches equipped with spar torpedoes, to attack the blockading fleet. Some torpedo boats were refitted steam launches, others, such as the CSS David class, were purpose-built. The torpedo boats tried to attack under cover of night by ramming the spar torpedo into the hull of the blockading ship, then backing off and detonating the explosive. The torpedo boats were not effective and were easily countered by simple measures such as hanging chains over the sides of ships to foul the screws of the torpedo boats, or encircling the ships with wooden booms to trap the torpedoes at a distance.

One historically notable naval action was the attack of the H. L. Hunley, a hand-powered submarine launched from Charleston, South Carolina, against Union blockade ships. On the night of February 17, 1864, the Hunley attacked the USS Housatonic. The Housatonic sank with the loss of 5 crew; the Hunley also sank, taking her crew of 9 to the bottom.

Major engagements

The first victory for the U.S. Navy during the early phases of the blockade occurred on April 24, 1861, when the sloop USS Cumberland and a small flotilla of support ships began seizing Confederate ships and privateers in the vicinity of Fort Monroe off the Virginia coastline. Within the next two weeks, Flag Officer Garrett J. Pendergrast had captured 16 enemy vessels, serving early notice to the Confederate War Department that the blockade would be effective if extended.[13]

Early battles in support of the blockade included the Blockade of Chesapeake Bay[14], from May to June 1861, and the Blockade of the Carolina Coast, August-December 1861.[15] Both enabled the Union Navy to gradually extend its blockade southward along the Atlantic seaboard.

The Battle of Mobile Bay, August 5, 1864, closed the last Confederate port in the Gulf of Mexico.

In December 1864, the Navy attacked Fort Fisher, which protected the Confederate's access to the Atlantic from Wilmington, North Carolina, the last open Confederate port.[16] The first attack failed, but with a change in tactics (and Union generals), the fort fell in January 1865, closing the last major Confederate port.

End of the blockade and its impact

As the Union fleet grew in size, speed and sophistication, more ports came under Federal control. After 1862, only three ports—Wilmington, North Carolina; Charleston, South Carolina; and Mobile, Alabama—remained open for the 75 to 100 blockade runners in business. Charleston was shut down by Admiral John A. Dahlgren's South Atlantic Blockading Squadron in 1863. Mobile Bay was captured in August 1864 by Admiral David Farragut (tied to the rigging of his flagship, he cried out, "Damn the torpedoes! Full steam ahead!"). Blockade runners faced an increasing risk of capture—in 1861 and 1862, one sortie in 9 ended in capture; in 1863 and 1864, one in 3. By war's end, imports had been choked to a trickle as the number of captures came to 50% of the sorties. Some 1,100 blockade runners were captured (and another 300 destroyed). British investors frequently made the mistake of reinvesting their profits in the trade; when the war ended they were stuck with useless ships and rapidly depreciating cotton. In the final accounting, perhaps half the investors took a profit, and half a loss. Some historians have argued, "The blockade, because it did not deny the South essential imports, failed to have a major military effect."[17] That analysis ignores the inability of the Confederacy to clothe and feed its remaining soldiers, or to use its long coastline to move troops and supplies by boat. Most economic analysis agrees the blockade crushed the Southern economy and decisively weakened the military's maneuverability and logistics.[18] Elekung (2004) concludes, "The fall of Fort Fisher and the city of Wilmington, North Carolina, early in 1865 closed the last major port for blockade runners, and in quick succession Richmond was evacuated, the Army of Northern Virginia disintegrated, and General Lee surrendered. Thus, most economists give the Union blockade a prominent role in the outcome of the war."

Bibliography

- Bennett, Michael J. Union Jacks: Yankee Sailors in the Civil War (2003)

- Blair, Dan. "'One Good Port': Beaufort Harbor, North Carolina, 1863-1864. North Carolina Historical Review 2002 79(3): 301-326. Issn: 0029-2494 Fulltext: in Ebsco

- Browning, Robert M., Jr., From Cape Charles to Cape Fear. The North Atlantic Blockading Squadron during the Civil War. University of Alabama Press, 1993.

- Buker, George E., Blockaders, Refugees, and Contrabands: Civil War on Florida's Gulf Coast, 1861-1865. University of Alabama Press, 1993.

- Cochran, Hamilton. Blockade Runners of the Confederacy. (1958). 350 pp.

- Elekund, R.B., Jackson J.D., and Thornton M., "The 'Unintended Consequences' of Confederate Trade Legislation." Eastern Economic Journal, Spring 2004)

- Surdam, David G. "The Union Navy's Blockade Reconsidered." Naval War College Review 1998 51(4): 85-107. Issn: 0028-1484

- Surdam, David G. Northern Naval Superiority and the Economics of the American Civil War. U. of South Carolina Press, 2001. 286 pp., the most detailed analysis of the impact online review

- Time-Life Books, The Blockade: Runners and Raiders. 1983.

- Wise, Stephen R., Lifeline of the Confederacy: Blockade Running during the Civil War. University of South Carolina Press, 1988, the standard scholarly history

Primary courses

- Durham, Roger S. High Seas and Yankee Gunboats: A Blockade-Running Adventure from the Diary of James Dickson. U. of South Carolina Press, 2005. 185 pp.

- Vandiver, Frank Everson, Confederate Blockade Running Through Bermuda, 1861-1865: Letters And Cargo Manifests (1947), primary documents

External links

- American Civil War Research & Discussion Group - Fields Of Conflict - Containing 1500+ Links And 400+ Articles.

- National Park Service listing of campaigns

- The Union Navy's Blockade Reconsidered

- Book review: Lifeline of the Confederacy

- Unintended Consequences of Confederate Trade Legislation

- The Hapless Anaconda: Union Blockade 1861-1865

- Sabine Pass and Galveston Were Successful Blockade-Running Ports By W. T. Block

Notes

- ↑ Wise (1998)

- ↑ Jenkins essay

- ↑ See Blockade essay

- ↑ Lincoln biography

- ↑ Time-Life, page 31.

- ↑ See National Park Service

- ↑ See U.S Naval Blockade

- ↑ See Blockade essays

- ↑ Time-Life, page 33.

- ↑ Blair (2002)

- ↑ Rhet Butler was the scoundrel in Gone With the Wind (1939) who became rich as a blockade runner.

- ↑ Time-Life, page 95.

- ↑ Time-Life, page 24.

- ↑ National Park Service

- ↑ National Park Service

- ↑ Charles M. Robinson, III, Hurricane of Fire: The Union Assault on Fort Fisher. (1998) and Amphibious Warfare: Nineteenth Century

- ↑ Archer Jones, "Military Means, Political Ends: Strategy," in Gabor S. Boritt, ed. Why the Confederacy Lost. (1992) p. 74

- ↑ See Surdam (1998) and Surdam (2004) for elaborate detail.