Scenography (set design).

Scenography (Set Design) is concerned with the environment of the play (the performance space) as it is realized on the stage.

| “The reality of a theatrical performance has no inherent connection with its realism, the degree of fidelity with which it reproduces or reflects the fact, as we say, of actual life. A play becomes real to the degree that any audience succeeds in identifying itself with the lives and deeds portrayed.” (Lee Simonson) |

The first rule of awareness is that everything is real. Everything we comprehend is part of reality, it is realistic. Theatre has a reality of its own; a logical construct and it is within this construct that set designers work. The designer is concerned with that aspect of the art form that Aristotle described as the manner of presentation; its spectacle. The designer is concerned with how the subject matter of the piece and (to some extent) the medium are visually offered to the audience.

Background:

Today theatre is considered a collaborative art form but prior to the sixteenth century the particular environment in which a play was set was the responsibility of the playwright for theatre was an aural entertainment. (See Conventions of Theatre) People went to the theatre to hear a play and they expected the playwright to conjure up the scene in language so that they could see it with their ‘minds eye’. Hamlet engages the players to entertain at Elsinore with the words “We’ll hear a play tomorrow.” and Shakespeare has his chorus in Henry V implore the audience to “Piece out the imperfections with your thoughts”. Shakespeare wrote for groundlings who could neither read nor write. New English was still a blossoming experience for his audience. His language use was varied, rich and at times subtle and often nuanced, providing a bountiful stimulus for the imagination and his audience delighted in the visual impact of it.

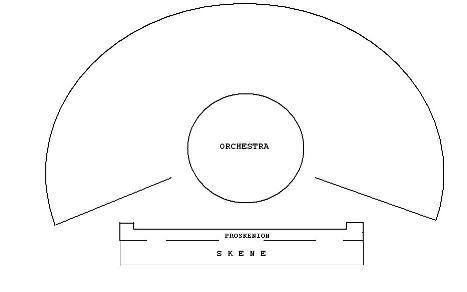

Set design as an integral ingredient of the director’s production concept is a relatively new phenomenon in the history of the theatre. In ancient Greek theatre Sophocles is reputed to have used painted panels (pinakes) or tapestries attached to the pillars of the façade of the front edge of the stage (proskenion) but there is little evidence to suggest that it was more than theatre decoration. The stage area was a long narrow porch attached to a wooden hut called a Skene from which our word scene is derived.

Traditionally Roman theatre performances were held in honor of one or more gods which became anathema to the emerging Christian church. Romans were comfortable with a bevy of gods and were quite willing to accommodate gods of other religions as long as they could maintain belief in their favorites. The intractability of the Christians brought them much grief until the Emperor Constantine (324 – 337) made Christianity lawful. Christian opposition, the internal political and social rot in the Roman Empire and the invasion of barbarian tribes eventually spelled the demise of the nine hundred year tradition of western theatre.

Ironically, it was the Christian church that resurrected theatre in the form of Liturgical Drama (in Latin) in the early part of the Tenth Century. Soon ecclesiastic dramas gave way to plays written by priest, depicting biblical stories and performed by church clerics on religious holidays. By the late Middle Ages (1300 – 1500) the steady secularization of religious plays required the performances to take place outside the churches. Guilds of craftsmen; bakers, brewers, goldsmiths, tailors and the like vied for the opportunity to stage a simple biblical story in the vernacular during religious festivals. The plays were divided into episodes assigned to particular guilds who built elaborate settings called mansions on which to stage their assigned piece. It has been reported that in the episode called the Last Judgment a giant ‘hell mouth’ opened and spat real smoke and flames. The episodes proved so popular and the crowds so great that the church decreed them to be occasions of sin and withdrew its patronage but the performances did not cease. The public had acquired a taste for theatre.

Stages (Types)

Treatment.