Marcello Malpighi

The 17th century Italian scientist, Marcello Malpighi (1628-1694), though not the first to employ the microscope to study tissue from living systems,[1] so extensively applied the newly invented optical instrument for that purpose, and so cleverly developed experimental techniques to extend its application thereto, that historians generally credit him as the 'Founder of Microscopic Anatomy', the latter discipline commonly referred to as histology. [2] [3]

Malpighi observed and reported on microscopic anatomical features of the spleen, kidneys, liver, lungs, urinary bladder, brain, spinal cord, skin, and numerous other animal and plant organs and tissues. He so changed the perspective on the anatomy of organisms, including that of humans, that a turning point occurred in the history of medicine that enabled the progress in research necessary to develop our modern understanding of the physiology of living systems.

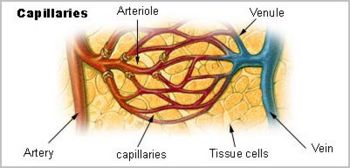

One notable example that helped secure his election to the History of Medicine's Hall of Fame, Malpighi's microscopic anatomical studies led him to identify, in 1661, first in the lungs and urinary bladder, the capillaries, the myriad minute (invisible to the naked eye) blood vessels that conveyed blood pumped by the heart from the arteries to the veins. In so doing, he supplied the missing link that the discoverer of the heart's function and the blood circulation, William Harvey (1578-1657), only could postulate must exist to complete the blood circuit from the heart's left to right ventricle through the body, and from the right to left ventricle through the lungs — the so-called greater and lesser circulations, respectively — circuits that Harvey's macroscopic (visible to the naked eye) anatomical studies, abetted by mathematical calculations, led him to infer.

Historians often compare Malpighi’s exploitation of the potential of the early microscope with Galilei Galileo’s creatively exploratory use of the early telescope:

If Robert Hooke's 1665 Micrographia was the most visually striking book of microscopy of its time, it was Malpighi who profoundly transformed anatomy by means of the microscope. Virtually all his publications show his virtuoso performance with that instrument. It seems impossible to escape the adroit analogy between, on the one hand, Galileo and the telescope and, on the other, Malpighi and the microscope. Both made of already available instruments remarkable research tools in astronomy and anatomy.[4]

The planet-revolving moons of Jupiter visualized with Galileo’s telescope gave sustenance to Copernicus’s discredit of the heliocentrism of Ptolemy, and the artery-to-vein connectivity visualized with Malpighi’s microscope gave sustenance to William Harvey’s discredit of the hepato-venocentrism of Galen.

According to Pearce: [3]

[Malpighi's] discovery of the capillary circulation was published in the form of two letters, ‘De Pulmonibus’, addressed to [his lifelong friend and colleague, Giovanni Alfonso] Borelli [famous Italian mathematician, physicist and physiologist], published at Bologna in 1661 and subsequently reprinted at Leiden and elsewhere. These letters also contained the first account of the vesicular structure of the human lung, and for the first time they made possible a theory of respiration.[3]

References and notes cited in text

- ↑ Note: Other pioneering 17th century microscopists: the Dutch (Delft) 1676 discoverer of microbes, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek (1632-1723); the ‘renaissance’ British scientist and 1665 describer of the first cells, Robert Hooke (1635-1703); the Dutch (Amsterdam) 1658 discoverer of red blood cells, Jan Swammerdam (1637-1680).

- ↑ Marcello Malpighi (Free Full-Text Article, Britannica Online).

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Pearce JMS. (2007) Malpighi and the Discovery of Capillaries. European Neurology 58:253-255.

- ↑ Meli DB. (2007) Mechanistic pathology and therapy in the medical Assayer of Marcello Malpighi. (Free full-text article) Med Hist 51:165-80. PMID 17538693.