Song Dynasty

- The content on this page originated on Wikipedia and is yet to be significantly improved. Contributors are invited to replace and add material to make this an original article.

The Song Dynasty (or Sung Dynasty) (960–1279 CE) was a ruling Chinese dynasty which presided over a sophisticated and culturally rich age in China, characterised by advancements in technology, the visual arts, music, literature, and philosophy. The culture of the elite scholar-officials replaced that of the aristocracy at the pinnacle of Chinese society, while general Chinese culture was enhanced by widespread printing, growing literacy, and appreciation for the various arts.

The visual arts

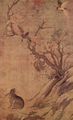

During the period of Song, Chinese painting reached new heights of sophistication with the matured development of Chinese landscape painting. In China this was called shan shui style painting, shan meaning mountain, and shui meaning river, as the two were always prominent features in Chinese landscape art. The making of glazed and translucent porcelain wares with complex use of enamels was also developed further during the Song period. Black and red lacquer-wares of the Song period featured beautifully-carved artwork of miniature nature scenes, landscapes, or simple decorative motifs. However, even though intricate bronze-casting, ceramics and lacquerware, jade carving, sculpture, architecture, and the painting of portraits and closely viewed objects like birds on branches were held in high esteem by the Song Chinese, landscape painting was paramount.[1] Chinese landscape artists mastered the formula of creating intricate and realistic scenes placed in the foreground, while the background pertained qualities of vast and infinite space, with distant mountain peaks rising out of high clouds and mist, as streaming rivers would run from afar into the foreground.[2]

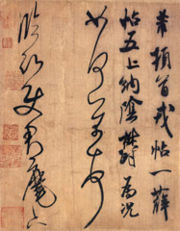

Culturally, the Song refined many of the developments of the previous centuries. This included refinements of the Tang ideal of the universal man, who combined the qualities of scholar, poet, painter, and statesman, but also historical writings, painting, calligraphy, hard-glazed porcelain and Chinese inkstones. Ever since the ancient Southern and Northern Dynasties period, painting became an art of high sophistication that was associated with the gentry class as one of their main pastimes. During the Song period there were avid art collectors that would often meet in groups to discuss their own paintings, as well as rate those of their colleauges and friends. The poet and statesman Su Shi (1037-1101) and his accomplice Mi Fu (1051-1107) often partook in these affairs, often borrowing art pieces to study and copy, or if they really admired the art piece then a persuasion to make a trade for it was often proposed.[3]

As mentioned with Emperor Huizong above, talented court painters were highly esteemed by the emperor and royal family. One of the greatest landscape painters given patronage by the Song court was Zhang Zeduan (1085–1145), who painted the original for the famous Along the River During Ching Ming Festival scroll. Emperor Gaozong of Song (1127-1162) once commissioned an art project of numerous paintings for the Eighteen Songs of a Nomad Flute, based on the woman poet Cai Wenji (177-250 AD) of the earlier Han Dynasty. During the Song period Buddhism saw a small revival since its persecution during the Tang Dynasty. This could be seen in the continued construction of sculpture artwork at the Dazu Rock Carvings.

Gallery

Autumn in the River Valley, by Guo Xi (c. 1020-1090 AD), 1072 AD.

Cats in the Garden, by Chinese painter Mao Yi, 12th century AD.

Two Finches, by Emperor Huizong of Song (r. 1100-1126 AD).

A Song Dynasty teapot in the Qingbai style, from Jingdezhen.

Literature and science

Chinese literature during the Song period contained a range of many different genres and was enriched by the social complexity of the period. Although the earlier Tang Dynasty is viewed as the zenith era for Chinese poetry (with Du Fu, Li Bai, Bai Juyi, etc.), there were still significantly famous poets of the Song era. This included the social critic and pioneer of the "new subjective style" Mei Yaochen (1002-1060), the politically controversial yet renowned master Su Shi (1037-1101), the eccentric yet brilliant Mi Fu (1051-1107), the premier Chinese female poet Li Qingzhao (1084-1151), and many others. Although it found its roots during the Liang Dynasty (502-557 AD), the ci form of Chinese poetry found its greatest acceptance and popularity during the Song Dynasty, and was used by most Song poets. The high court Chancellor Fan Zhongyan (989-1052), ardent Neo-Confucian Ouyang Xiu (1007-1072), the great calligrapher Huang Tingjian (1045-1105), and the military general Xin Qiji (1140-1207) were especially known for their ci poetry, amongst many others.

Historiography

The writing of history remained prominent during the Song, as it had in previous ages and would in successive ages of China. Along with Song Qi, the essayist and historian Ouyang Xiu (1007-1072) were responsible for compiling the New Book of Tang by 1060, covering the history of the Tang Dynasty. Chancellor Sima Guang (1019-1086), the political nemesis of Wang Anshi (1021-1086), was responsible for heading a team of scholars that compiled the enormous historical work of the Zizhi Tongjian, a universal history completed in 1084 with a total of over 3 million written Chinese characters in 294 volumes. It covered the major themes and intricate nuances of Chinese history from the Warring States (403 BC) all the way up to the beginning of the Song Dynasty. In 1189 it was compiled and condensed into fifty-nine books by Zhu Xi (1130-1200), while this project was totally complete with the efforts of his disciples around the time of his death in 1200.[4] There were also very large encyclopedic works written in the Song period, such as the Four Great Books of Song compiled first by Li Fang in the 10th century and fully edited by the time of Cefu Yuangui in the 11th century. The largest of these was the 1013 publication of the Prime Tortoise of the Record Bureau, a massive encyclopedia consisting of 9.4 million written Chinese characters divided into 1000 volumes. There were are also rhyme dictionaries written during the Song Dynasty, such as the Jiyun of 1037.

Religion

Although Neo-Confucianism became dominant over Buddhism in China during this period, there was still a significant amount of Buddhist literature. For example, there was the collection of Zen Buddhist kōans in the Blue Cliff Record of 1125, which was expanded by Yuanwu Keqin (1063-1135).

Science and technology

There were many technical and scientific writings during the Song period. The two most eminent authors of the scientific and technical fields were Shen Kuo (1031-1095) and his contemporary Su Song (1020-1101). Shen Kuo published his Dream Pool Essays in 1088 AD, an enormous encyclopedic book that covered a wide range of subjects, including literature, art, military strategy, mathematics, astronomy, meteorology, geology, geography, metallurgy, engineering, hydraulics, architecture, zoology, botany, agronomy, medicine, anthropology, archeology, and more.[5] As for Shen Kuo's equally brilliant peer, Su Song created a celestial atlas of five different star maps, wrote the 1070 pharmaceutical treatise of the Ben Cao Tu Jing (Illustrated Pharmacopoeia), which had the related subjects of botany, zoology, metallurgy, and mineralogy, and wrote his famous horological treatise of the Xin Yi Xiang Fa Yao in 1092, which described in full detail his ingenious astronomical clocktower constructed in the capital city of Kaifeng. Although these two figures were perhaps the greatest technical authors in their field during the time, there were many others. For producing textiles, Qin Guan's book of 1090, the Can Shu (Book of Sericulture), included description of a silk-reeling machine that incorporated the earliest known use of the mechanical belt drive in order to function.[6] In the field of agronomy, there was the Jiu Huang Huo Min Shu (The Rescue of the People; a Treatise on Famine Prevention and Relief) edited by Dong Wei in the 12th century, the Cha Lu (Record of Tea) written by Cai Xiang in 1060, the Zhu Zi Cang Fa (Master Zhu on Managing Communal Granaries) written by Zhu Xi in 1182, and many others.[7][8] There were also great authors of written works pertaining to geography and cartography during the Song Dynasty, such as Yue Shi (his book in 983), Wang Zhu (in 1051), Li Dechu (in 1080), Chen Kunchen (in 1111), Ouyang Wen (in 1117), and Zhu Mu (in 1240).[9]

Philosophy

Song intellectuals sought answers to all philosophical and political questions in the Confucian Classics. This renewed interest in the Confucian ideals and society of ancient times coincided with the decline of Buddhism, which the Chinese regarded as foreign and offering few practical guidelines for the solution of political and other mundane problems. However, Buddhism in this period continued as a cultural underlay to the more accepted Confucianism and even Daoism, both seen as native and pure by conservative Neo-Confucians. The continuing popularity of Buddhism can be seen with strong evidence by achievements in the arts, such as the 100 painting set of the Five Hundred Luohan, completed by Lin Tinggui and Zhou Jichang in 1178.

The conservative Confucian movement could be seen before the likes of Zhu Xi, with staunch anti-Buddhists such as Ouyang Xiu of the 11th century. In his written work of the Ben-lun, he wrote of his theory for how Buddhism had so easily penetrated Chinese culture during the earlier Southern and Northern Dynasties period. He argued that Buddhism became widely accepted when China's traditional institutions were weakened at the time. This was due to many factors, such as foreign Xianbei ruling over the north, and China's political schism that caused warfare and other ills. Although Emperor Wen of Sui (r. 581–604) abolished the Nine Ranks in favor of a Confucian-taught bureaucracy drafted through civil service examinations, he also heavily sponsored the popular ideology of Buddhism to legitimate his rule. Hence, it was given free reign and influence to flourish and dominate Chinese culture during the Sui and Tang periods while Confucianism was reverted to "stale archaism".[10] Ou-yang Xiu wrote:

"This curse [Buddhism] has overspread the empire for a thousand years, and what can one man in one day do about it? The people are drunk with it, and it has entered the marrow of their bones; it is surely not to be overcome by eloquent talk. What, then, is to be done?[11]

In conclusion on how to root out the 'evil' that was Buddhism, Ou-yang Xiu presented a historical example of how it could be uprooted from Chinese culture (Wade-Giles spelling):

Of old, in the time of the Warring States, Yang Chu and Mo Ti were engaged in violent controversy. Mencius deplored this and devoted himself to teaching benevolence and righteousness. His exposition of benevolence and righteoussness won the day, and the teachings of Mo Ti and Yang Chu were extirpated. In Han times the myriad schools of thought all flourished together. Tung Chung-shu deplored this and revived Confucianism. Therefore the Way of Confucius shone forth, and the myriad schools expired. This is the effect of what I have called "correcting the root cause in order to overcome the evil".[12]

Although Confucianism was cast in stark contrast to the perceived alien and morally-inept Buddhism by those such as Ou-yang Xiu, Confucianism nonetheless borrowed ideals of Buddhism to provide for its own revival. From Mahayana Buddhism, the Bodhisattva ideal of ethical universalism with benevolent charity and relief to those in need inspired those such as Fan Zhongyan and Wang Anshi, along with the Song government.[13] In contrast to the earlier heavily Buddhist Tang period, where wealthy and pious Buddhist families and Buddhist temples handled much of the charity and alms to the poor, the Song Dynasty government took on this ideal role instead, through its various programs of welfare and charity (refer to Society section).[14] In addition, the historian Arthur F. Wright notes this situation during the Song period, with philosophical nativism taking from Buddhism its earlier benevolent role:

It is true that Buddhist monks were given official appointments as managers of many of these enterprises, but the initiative came from Neo-Confucian officials. In a sense the Buddhist idea of compassion and many of the measures developed for its practical expression had been appropriated by the Chinese state.[15]

Although Buddhism lost its prominence in the elite circles and government sponsorships of Chinese society, this did not mean the disappeance of Buddhism from Chinese culture. Zen Buddhism continued to flourish during the Song period, as Emperor Lizong of Song had the monk Wuzhun Shifan share the Chán (Zen) doctrine with the imperial court. Much like the Eastern Roman Emperor Julian the Apostate promoting Roman paganism and Theurgy amongst the leading members of Roman society while pushing Christianity's influence into the lower classes, so too did Neo-Confucians of the 13th century succeed in driving Buddhism out of the higher echelons of Chinese society.[16]

In terms of Buddhist metaphysics, the latter influenced the beliefs and teachings of Northern Song-era Confucian scholars such as Cheng Hao and Cheng Yi (who were brothers), the former being one of the tutors of Zhu Xi. They emphasized moral self-cultivation over service to the ruler of the state (healing society's ills from the bottom-up, not the top-down), as opposed to statesmen like Fan Zhongyan or Su Shi, who pursued their agenda to advise the ruler to make the best decisions for the common good of all.[17] The Cheng brothers also taught that the workings of nature and metaphysics could be taught through the principle (li) and the vital energy (qi). The principle of nature could be moral or physical, such as the principle of marriage being moral, while the principle of trees is physical. Yet for principles to exist and function normally, there would have to be substance as well as vital energy.[17] This allowed Song intellectuals to validate the teachings of Mencius on the innate goodness of human nature, while at the same time providing an explanation for human wrongdoing.[17] In essence, the principle underlying a human being is good and benevolent, but vital energy has the potential to go astray and be corrupted, giving rise to selfish impulses and all other negative human traits.

The Song Neo-Confucian philosophers, finding a certain purity in the originality of the ancient classical texts, wrote commentaries on them. The most influential of these philosophers was Zhu Xi (1130–1200), whose synthesis of Confucian thought and Buddhist, Taoist, and other ideas became the official imperial ideology from late Song times to the late 19th century. The basis of his teaching was influenced by the Cheng brothers, but he greatly extended their teachings, forming the core of Neo-Confucianism. This included emphasis on the Four Books: the Analects, Mencius, Doctrine of the Mean, and the Great Learning (the latter two being chapters in the ancient Book of Rites). His viewpoint was that improvement of the world began with improvement of the mind, as outlined in the Great Learning.[18] His approach to Confucianism was shunned by his contemporaries, as his writings were forbidden to be cited by students taking the Imperial Examinatoins. However, Emperor Lizong of Song found his writing to be intriguing, reversing the policy against him, and making it a requirement for students to study his commentaries on the Four Books.[18]

As most historians and scholars agree today, Zhu Xi's Neo-Confucian philosophy evolved into a rigid official creed, which stressed the one-sided obligations of obedience and compliance of subject to ruler, child to father, wife to husband, and younger brother to elder brother (as opposed to the significant level of social freedom enjoyed by women during the earlier Tang Dynasty). The effect was to inhibit the societal development of pre-modern China, resulting both in many generations of political, social, and spiritual stability and in a slowness of cultural and institutional change up to the 19th century. Neo-Confucian doctrines also came to play the dominant role in the intellectual life of Korea, Vietnam, and Japan until modern times.

Festivities

In ancient China there were many domestic and public pleasures in the rich urban environment unique to the Song Dynasty (refer to Society of Song Dynasty). In addition, there were many annual festivities held throughout the year in medieval China that had much of the populace participating and enriched cultural awareness. The widely popular Lantern Festival was held every 15th day of 1st lunar month. According to the scholar official Zhou Mi (1232-1298 AD), during the Xiao-Zong period (1163-1189 AD) the best lantern festivals were held at Suzhou and Fuzhou, while Hangzhou was also known for the its great variety of colorful paper lanterns, in all shapes and sizes.[19] Written in his memoirs, Meng Yuan-lao (active 1126-1147) recalled how the earlier Northern Song capital at Kaifeng would host festivals with tens of thousands of colorful and brightly-lit paper lanterns hoisted on long poles up and down the main street, the poles also wrapped in colorful silk with numerous dramatic paper figures flying in the wind like fairies.[19] There were also other venerated holidays, such as the Qingming Festival, as it was supposedly this period of the year that was depicted in the artwork (mentioned above) by the artist Zhang Zeduan (although some would argue the painting actually represented the time of autumn in the year).

With the advent of the discovery of gunpowder in China, lavish fireworks displays could also be held during festivities. For example, the martial demonstration in 1110 AD to entertain the court of Emperor Huizong, when it was recorded that a large fireworks display was held alongside Chinese dancers in strange costumes moving through clouds of colored smoke in their performance.[20]

Footnotes

- ↑ Morton, 104.

- ↑ Morton, 105.

- ↑ Ebrey, 163.

- ↑ Partington, 238.

- ↑ Needham, Volume 1, 136.

- ↑ Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 107-108.

- ↑ Needham, Volume 6, Part 2, 621.

- ↑ Needham, Volume 6, Part 2, 623.

- ↑ Needham, Volume 3, 521.

- ↑ Wright, 92.

- ↑ Wright, 88.

- ↑ Wright, 89.

- ↑ Wright, 93.

- ↑ Wright, 93-94.

- ↑ Wright, 94.

- ↑ Brown, 93.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Ebrey et al., 168.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Ebrey et al., 169.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Needham, Volume 4, Part 1, 128.

- ↑ Kelly, 2.