South Vietnam's ground war, 1972-1975

After the full implementation of the Vietnamization doctrine, the U.S. saw the Army of the Republic of Viet Nam (ARVN) as taking responsibility for ground combat in South Vietnam between 1972 and 1975, with both direct air and naval combat support from U.S. forces, as well as combat support in areas such as intelligence and communications, and combat service support in supply and maintenance.

This article excludes the final North Vietnamese offensive and fall of South Vietnam, but it should be understood that North Vietnam had been steadily encroaching on South Vietnam since 1972. While some of the 1975 attack came directly from the North, even those attacks had come from areas under the Provisional Revolutionary Government, which was under the effective control of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam|North Vietnamese governing Politburo. There was a specific 1974 decision for the final attack, but even it came in phases.

In the face of declining U.S. popular support of the war, the Nixon Administration had adopted the Vietnamization doctrine, in which U.S. ground troops would no longer fight in South Vietnam, although, subject to negotiations with the Communists, there would be U.S. foreign military assistance organizations|U.S. foreign military assistance to the South, and always the threat of U.S. air and naval attacks against the North. While the North Vietnamese would not directly fight U.S. ground troops, the potential of their return, or of much greater support to the South Vietnamese, would be an incentive to serious negotiations, assisted by other Communist powers that also believed an end to the confrontation was in order.

Nixon's larger strategy was to convince Moscow and Beijing they could curry American favor by reducing or ending their military support of Hanoi. He assumed that would drastically reduce Hanoi's threat. Second, "Vietnamization" would replace attrition. Vietnamization meant heavily arming the ARVN and turning all military operations over to it; all American troops would go home.

American public opinion either did not accept that the North Vietnamese took a long-term view, or was willing to ignore it in the interest of disengagement. In hindsight, the North Vietnamese continued to target American opinion, to reduce support to the South and make a serious reinforcement politically unacceptable. They never rejected their intention to conquer the south.

They did, however, abandon their General Offensive-General Uprising doctrine, replacing it with a largely conventional warfare model. Their need to fight units of full U.S. capability became moot, because even Vietnamized troops would not have the combat power of American troops. Further, South Vietnamese politics, as well as the long experience needed to qualify a thoroughly capable general, would create a disparity of with the North Vietnamese, who retained and encouraged competent commanders.

Saigon had still not been able to create widespread popular support or run an effective administration. Even after its first defeats in 1975, according to Bui Diem, South Vietnam's Ambassador to the United States between 1969 and 1972, said that President Thieu, even after the resignation of Richard M. Nixon, believed that President Gerald Ford did have the authority to order a response. The Ambassador said that Thieu did not really understand American politics and the realities of lack of popular support for intervention. Thieu was getting poor advice; his Assistant for National Security Affairs, Gen. Dan Van Quang, did not want to give Thieu bad news.

The Minister of Planning, Nguyen Tien Hung, was overoptimistic: in presenting his review of proposed 1974-1975 aid to Thieu, Hung saud his sources, "close to the Pentagon", said that $850 million had been earmarked for possible bombing of the North. Bui Diem, and the current Ambassador, Tran Kim Phuong, said this was wishful thinking, but he believed Thieu wanted encouragement and was more prone to listen to Hung than to people with more direct experience with the United States. The optimism was increased by military staff reports that procedures had been established for requesting air support from the U.S., although there was no indication that U.S. policy officials approved it. The RAND authors also quoted sources close to Thieu as his not understanding that the U.S. Congress had real power.[1]

By 1972, the North Vietnamese committed to a conventional invasion against the South. While it was repelled, the eventual Paris treaty further restricted U.S. involvement, and the endgame came with a new conventional invasion that led to the fall of south Vietnam in 1975. It defeated the South Vietnamese government, but also ended a war of decades.

The context of talks

Since 1969, there had been acknowledged, but also initially secret, negotiations generally called the Paris Peace Talks. On January 25, 1972, President Richard Nixon|Richard M. Nixon disclosed the details of the secret agreement, which included an agreement for the U.S. to withdraw its troops, replace Army of the Republic of Viet Nam (South Vietnamese) equipment on a piece-by-piece basis, and "the United States will stop all its military activities against the territory of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam."[2]

Cambodia: a first sanctuary breached

North Vietnam, for different reasons, had always used sanctuaries in Cambodia and Laos. Operating from Cambodia, their troops had a short exposure to being attacked while moving against Saigon and the Mekong Delta. They also had some major command centers not far into Cambodia.

Nixon, with Creighton Abrams' approval, believed that major ground offensives into Cambodia, by combined U.S. and South Vietnamese forces, would change the balance of power and improve the South Vietnamese chances. There had been an unacknowledged bombing program that was not decisive. In April, two major but mutually supporting operations took place, one into the Parrot's Beak area and the other the Dragon's Jaw.

The Parrot's Beak, according to Nixon's speech on April 30, contained major command facilities. [3] It is the part the Cambodian province of Svay Rieng that juts into the southern Vietnamese provinces of Tay Ninh and Long An provinces. It was the site of a U.S. operation against North Vietnamese sanctuaries in 1970, and a North Vietnamese operation against the Khmer Rouge in 1978.[4]

1972

1972 was to mark a basic change in North Vietnamese tactics, when they switched from guerrilla and hit-and-run raids to conventional combined arms combat. While the PAVN started using tanks with artillery and infantry, they did not show tactical mastery. In particular, they would allow tanks to operate alone, in terrain where enemy infantry could attack them with short-range weapons. They also seemed to have difficulty in keeping their tanks fueled.

While the Politburo of North Vietnam changed their military methods radically from those of the Tet Offensive, they still hoped for their military success to trigger a General Offensive-General Uprising|popular uprising. New draft laws produced over one million well-armed regular soldiers, and another four million in part-time, lightly armed self-defense militia.

Easter invasion

North Vietnam began preparing the battlefield for its major invasionm which they called Operation Nguyen Hue and the non-Communist side called the Easter (or Eastertide) Offensive, involved three separate corps-level attacks by 12 divisions. They built an air defense network to protect what was to be their rear areas, north of the DMZ. This included 9K32M Strela-2 (NATO reporting name SA-7 GRAIL) surface-to-air missiles that shot down three U.S. fighter-bombers in February.[5]

The main attack came with the start of the monsoon season, which prevented close air support and even good artillery fire control. When artillery was available, however, the PAVN 130mm guns had greater range than ARVN howitzers, and could be countered only by tactical aircraft.

In March, 1972 Hanoi invaded on three fronts:

- Northern provinces with a six-division force

- Central highlands, driving for the coast, using three divisions

- Saigon area, employing three divisions

The bulk of this campaign ended by June, but battle continued, in some areas, until September. While the North took enormous casualties, they took and held ground. Unquestionably, U.S. airpower, including B-52s and close air support by AC-130s and fighter-bombers, played a key part. Thieu worried even more about his ability to resist without that support. [6] Nevertheless, the ARVN ground forces fought hard. GEN Abrams summarized

I doubt the fabric of this thing could have held together without U.S. air, but the thing that had to happen before that was the Vietnamese, some numbers of them, had to stand and fight. If they do not do that, ten times the air we've got wouldn't have stopped them.[7]

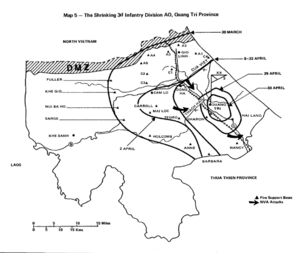

Operations in the North (RVN I Corps area)

Image:1972-Easter-I CTZ.png|left|thumb|400px I Corps tactical zone, at the start of the invasion, was under the command of a Thieu loyalist, Hoang Xuan Lam, who had commanded the failed 1971 Operation Lam Son 719. I Corps had three infantry divisions, of which the 1st and 2nd were experienced. It also had a separate infantry regiment, a Ranger Group of 3 regular and 6 border defense battalions, an armored brigade, Marines and Airborne in reduced division strength, 6 Regional Force battalions, and corps engineers and artillery.[8]

The northern operation, launched on March 31, used three divisions for the attack, followed later by another three divisions. It was under the direct control of the national command in Hanoi, and was timed for the beginning of the monsoon season, which would limit air support. The PAVN 308th, 304th Divisions moved into Quang Tri province, followed by the 324B division attacking ARVN positions west of Hue.

Receiving the brunt of the attack, however, was the newly formed 3rd ARVN Division, under BG Vu Van Giai, reinforced with the 147th Marine Brigade, 1st Airborne Brigade (detached from the Airborne Division), and 5th Armored Brigade. This was an odd mixture of troops for a critical area; the 3rd Division had only one regiment of experienced soldiers, while its other two regiments were made up of troops "who had been sent to the northernmost province of SVN as a punishment."[9] Truong, however, said that the battalions of the 3rd were experience, but the division and two of the regimental headquarters were new. Further, it was still receiving communications equipment and artillery, and it was not ready to fight a large conventional action.[10]

While the RVN Marines and Airborne had excellent reputations, they were not used in the best possible way. Given their skill, assigning them to a fixed defense line prevented their use as a mobile reserve. An army may place low-quality troops on a border, to pin the enemy while more powerful and mobile units maneuver for a counterattack, but, in fairness, the ARVN simply may not have had enough soldiers to cover the area and leave adequate reserves.

Further complicating matters, while the Rangers were attached to the 3rd Division, their own group headquarters stayed in Danang, under COL Trang Cong Lieu; the Rangers would often not comply with orders from BG Giai until they had confirmed them with COL Lieu. In like manner, the Marine Division headquarters was in Hue, but not subordinate to the I Corps commanding general. Again, when BG Giai issued an order, it might not be followed by the Marines until they confirmed it with their headquarters. BG Giai eventually had theoretical control of 9 brigades with a total of 23 battalions, supervision of province and district level forces, and corps artillery and logistics within his operational area. Even if he had all the communications equipment that would normally be assigned to a division, and he did not, and there were no conflicting order from other headquarters, this was far too many unit for him to control. [11] The traditional military rule of thumb is a commander can reasonably control 3 to 5 maneuver units, plus supporting troops.

MG Lam, the corps commander, did not assist BG Giai, but focused on planing a counteroffensive. First, he thought of moving north, but eventually changed to counterattacking west, with the 3rd division as the heart of the attack, to go in on April 14. Not only did confusing orders go to his Marines and Rangers, MG Lam would also give direct orders down to battalion level.[12]

These forces fell back, first to Dong Ha. They then linked to a defense line manned by the rest of the Airborne Division and another Marine brigade, south of the My Chanh River. There was a disorderly retreat, compounded by bad weather limiting the use of air support. Throughout April, the PAVN continued to press toward Quang Tri, which was abandoned on May 1.

While the 3rd division broke completely, the Marines held, and, with a new corps commander, BG Ngo Quang Truong replacing Gen. Lam,[13] reorganized and counterattacked from the Hue area. When Hue held, the PAVN fell back, and came under B-52 attack. During this time, Operation Linebacker I was becoming increasingly effective in interdicting the PAVN supply lines.

Given maneuvering room, Truong's rebuilt force of Airborne and Marine divisions came together to attack Quang Tri of May 29. They also launched an assault to retake Hue.It was not a short campaign, but they retook Quang Tri on September 15, which gave Henry Kissinger negotiating leverage in the Paris Peace Talks.

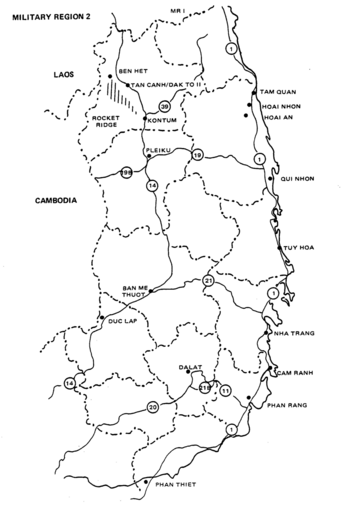

Operations in Central Vietnam (RVN II Corps)

II Corps tactical zone had an unusual organizational structure. MG Ngo Dzu, the corps commander, had John Paul Vann as his senior adviser. Vann, while technically a civilian, had operational control of U.S. assets, and had maneuvered into the equivalent of a U.S. Army two-star slot. He had an actual Army brigadier general, George Wear, as "deputy for military functions" to maintain the legality of a military officer commanding troops. [14]

Under the control of PAVN Military Region V, attacks by the B-3 Front, under Hoand Minh Thao, began on April 23, with the NVA 3rd Division feinting at Binh Dinh, while the 2nd and 10th Divisions attacked Kontum, originally held by the ARVN 22nd division, under COL Le Duc Dat which, over the protests of its armored component commander and U.S. adviser., used tanks as fixed defenses. Still mobile, however, was the 52nd Combat Aviation Battalion. [15]

The division operations center at Tan Canh was overrun, as was a strongpoint at Dak To. COL Philip Kaplan, the U.S. senior advisor, had seen the collapse coming, and made arrangements to evacuate. Vann had been surprised by actually seeing PAVN tanks in the attack.

On April 24th, COL Dat and his staff were last seen, waiting fatalistically; according to Heslin they were captured and taken to North Vietnam, although Sheehan wrote that he may have committed suicide.[16] Vann, was airborne during the battle, and directed the air support against PAVN tanks approaching the compound. He also evacuated Kaplan and the other advisers, crashing on the last trip, but all survived. When the command post was overrun, Gen. Dzu ordered the troops manning the firebases to retreat. They did so, without destroying their howitzers or ammunition.

The PAVN consolidated, including making use of captured artillery, between 25 April and 9 May, attacking Polei Kleng and Ben Het Ranger camps along their supply line. While Polei Kleng fell on May 9th, Ben Het held.

Both sides introduced new technology On the 9th, Ben Het had been assisted by a new weapons, helicopters firing the early XM26 model BGM-71 TOW|TOW antitank missile. During their attack, the PAVN had used ground-fired antitank missiles, the Soviet 9M14M Malutka/NATO designation AT-3 SAGGER.

The ARVN 23rd division, making especially good use of its tanks, threw back the attack at Kontum. Its commander, BG Ly Tong Ba, had commanded South Vietnam's first mechanized infantry company, in 1962, using M113 (armored personnel carrier)|M113 armored personnel carriers at the Battle of Ap Bac, although Vann had cursed him there as timid. As well as using his armor, he trained his infantry in the use of the M72 light antitank weapon. [17] Ironically, Vann had decided Ba was honest and, while not the greatest of commanders, was more competent than most ARVN officer. Vann had become Ba's patron and had helped him gain his rank. Vann assigned COL R.M. Rhotenberry, a trusted deputy, to stay with Ba. When the NVA were massing for their final attack on Kontum, Ba and Rhotenberry were able to trap them in the target "box" for multiple B-52 strikes. By this time, Dzu had been replaced as corps commander by Nguyen Van Toan, another Vann protege. Vann flew President Nguyen Van Thieu to Kontum, and pinned general's stars on Ba. Vann had an extra pair if Thieu forgot.

After the worst of the fighting, the 22nd Division began to recover, securing the two key roads, National Highway 1 (Vietnam)|Highway 1 (QL-1) on the coast, and National Highway 19 (Vietnam)|Highway 19 (QL-19) to Pleiku. Keeping Route 19 open was the job of two Armored Cavalry Squadrons. The division itself, headquartered in Binh Dinh, had four infantry regiments covering the area, and a reserve Armored Cavalry Squadron in Bong Son and two regiments of Rangers, one east of Tam Quan, and the other east of Phu Cu. The weakened PAVN 3rd Division was in the An Lao Valley, so there was a fairly balanced situation in Binh Dinh province.[18]

Vann died in a helicopter crash on June 9.[19]

Operations in the Saigon arrea (RVN III Corps)

To understand the III Corps environment, one cannot look only at South Vietnam proper, but the adjacent base areas in Cambodia. The Communists used Cambodia more as a base for operations against III and IV CTZ, rather than merely as a transit corridor as in Laos further north.

Image:1972-Easter-III CTZ+Cambodia.png|thumb|375px|III Corps CTZ and Cambodian base areas

Beginning on April 2, the composite PAVN/VC 5th Division attacked the firebase at Lac Long in Tay Ninh province, secured a position there, and moved against their main targets at Loc Ninh, Quan Loi and An Loc. These towns, with airfields, were positioned along National Highway 13 (Vietnam)|Highway 13 to Saigon. The Communists intended to hold ground and create a regional government that could be represented in future negotiations.Cite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag

Before the attack, ARVN forces in An Loc consisted of elements of the 9th division, the 3rd Ranger Group, and provincial troops. Reinforcements fro the 1st Airborne Brigade and 81st Airborne Ranger Brigade were airlifted to a landing zone 3km southeast of An Loc, and had to fight their way into the city. Still, the total defense was 6,350 men under BG Le Van Hung. It should be noted that except for Marines, elements of every part of the ARVN strategic reserve was part of the defense. President Nguyen Van Thieu called An Loc, under 24 hour shellfire, the symbol of South Vietnamese resistance, and sent in his palace guards as reinforcements. [20]

While the first attack, starting with a strong artillery preparation, pushed the 8th Regiment of the 5th Division, and the 3rd Ranger Group, from a hill and the airstrip. U.S. AC-130 gunship support stopped the infantry advance. As was the ARVN, the PAVN was still inexperienced in combined arms operations, a basic rule of which is that tanks always operate with infantry; the two branches complement one another. PAVN tanks, however, pushed on by themselves, and seven were destroyed in the attack, some by young Self-Defense force soldiers.

The next attack came on the 15th, and, again, they sacrificed tanks sent in without infantry. A B-52 strike hit the regimental headquarters, and the attack was called off.

May 11 was the day of the most intense assault, with one PAVN division striking from the northeast and another from the southwest, both with artillery preparation. By nightfall, the situation was in doubt; NVA forces came within a few hundred meters of the division command post. On the next day, while the PAVN tried to penetrate, they were pushed back by the garrison, assisted with close air support.

During the battles, there had been continuing suppression of enemy air defense, and, by early June, helicopters could survive to land in An Loc. On June 19, the ARVN 21st division, reinforced with another infantry regiment, and the 9th Armored Cavalry Regiment, broke through on Highway 13.

Stabilization and Provisional Government

Communist forces declared a Provisional Revolutionary Government (PRG) in areas in the north, and in Phuoc Long province west of Saigon. It received diplomatic recognition from the Communist world, giving leverage in the Paris Peace Talks, and served as one of the launch points of the 1975 invasion.

In the I Corps tactical zone area, the 17th parallel, which had previously defined the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) as the border, was in PAVN hands. Communist forces were now able to develop a transportation corridor from Dong Hoi to Dong Ha. and create another route, along National Highway 9 (Vietnam) | National Highway 9 (QL9) between Dong Ha and Khe Sanh. Clearing Western Quang Tri allowed the PAVN to build a second corridor from Khe Sanh to Kontum, where the PAVN B-3 Front, its regional headquarters for the Central Highlands was located. While the PAVN Fronts and Military Regions did not match the ARVN Corps tactical zones, this activity, which had taken place within both I CTZ and II Corps tactical zone|II CTZ [21]

Improvements in the weather allowed the U.S. to interdict the PAVN supply lines, and their offensive slowed; they moved back to secure an area south of the DMZ. [22] [23] The PRG areas now contained five PAVN divisions. [24]

The RVN relaxes

After the failed Easter Offensive the Thieu government made a fatal strategic mistake, going to a static defense and not refining its command and control for efficiency, not political reward. Control of military forces remained at the corps level, which a special problem for the Republic of Vietnam Air Force. There was also a lack of planning to operate as a national military, to cope with simultaneous attacks against multiple Corps tactical zones.

There was no central command that could order the Air Force, which was of substantial size, to concentrate on battlefield air interdiction of specific areas on the Ho Chi Minh trail or other critical points. Essentially, the aircraft only provided close air support.

The departure of American forces and American money lowered morale in both military and civilian South Vietnam. Desertions rose as military performance indicators sank, and no longer was the US looking over the shoulder demanding improvement.

In the North, Some ground north of My Chanh was regained by the Airborne Division on the East and Marine Division on the West. On September 14, the RVN Marines reentered Quang Tri.

In the Central Highlands, ARVN successes in the Kontum area isolated it from the terrain north and west of it; the PAVN gradually, while fighting to the end of 1972, let them build a base at Duc Co and extend the supply line to Binh Long Province. Still, they were able to retake Kontum by mid-June. [25]

By the end of December. An Loc, 50 miles/90 kilometers kilometers north of Saigon, was secure. Command had passed from the 18th Division to the lighter forces of the III Corps Ranger Command. The rest of Binh Long province except the capital at An Loc and a base at Chon Thanh, connected by National Highway 13 (Vietnam)|Highway QL-13 was under PAVN control. These two bases soon became completely dependent on supply by air, since only major operations could travel Highway 13. Just as the North Vietnamese controlled access to An Loc, they controlled access to Phuoc Binh (also called Song Be), the capital of Phuoc Long province.

One PAVN regiment, the 95C, was known to be in the An Loc area. That regiment was part of the 9th Division, which had moved its 272d Regiment to the vicinity of Bo Duc in northwestern Phuoc Long Province for rest and refitting. Its 271st Regiment of Chon Thanh in southern Binh Long Province in position to block the ARVN from using National Highway 13 (Vietnam)|Route 13 between Chon Thanh and An Loc; it also could move against Chi Linh and Don Luan (also known as Dong Xoai).

On other side, the PAVN had been badly mauled--the difference was that it knew it and it was determined to rebuild. Giap took three years to rebuild his forces into a strong conventional army. Without constant American bombing it was possible to solve the logistics problem by modernizing the Ho Chi Minh trail with 12,000 more miles of roads, as well as a fuel pipeline along the Trail to bring in gasoline for the next invasion.[26]

1973

As soon as the Paris accords were signed, President Nguyen Van Thieu, according to Hanoi, both said, to an unspecified audience. "the cease-fire does not at all mean the cessation of the war" but also refused to tell his troops about the signing. He had the ARVN launch attacks in various areas claimed by the Provisional Revolutionary Government (PRG). [27]

The rice war

While the battles in the northern and central areas were for control of land, those of the Mekong Delta, IV Corps tactical zone were for something even more basic: rice. The Mekong Delta is the richest rice-growing area of Southeast Asia. What became known as the "rice war" was seen from quite different perspectives from the standpoint of the Government of Vietnam, the Vietnamese Communists, the Cambodian Communists, and the people of South Vietnam.

Very little of the PAVN's rice came from North Vietnam, but from the delta, and the rice-producing areas of Cambodia adjacent to it. This was not a simple matter of ARVN vs. PAVN; Cambodia had its own internal battle between the government forces and the Communist Khmer Rouge. Marx notwithstanding, the Khmer Rouge had no particular desire to unite with the soldiers of North Vietnam. In fact, the Khmer Rouge wanted the PAVN out of Cambodia as much as the South Vietnamese wanted the PAVN out of their country.

The South Vietnamese had to be concerned with every phase of rice production and distribution. In September 1973, rice was becoming short in Saigon, due to an early drought.

In 1972, the total crop was 465,500 metric tons, but production of only 326,500 metric tons was expected from the Delta in 1973. Floods had destroyed much of the rice harvest and stored rice further north. [28]

In 1972, South Vietnamese intelligence estimated 58,000 metric tons of rice had been collected in the delta, and sent to Communist units in II and III Corps. Consequently, the PAVN needed to take control of more hamlets that grew rice and of more canals over which rice was shipped. They had to protect their own rice-gathering units, and also block ARVN units that aimed for the storehouses rather than the rice gatherers. From the South Vietnamese military perspective, there was a need to deny rice to the enemy.[28]

In principle, there was a need to make sure both that rice, as well, went to the people of South Vietnam, and was denied to the enemy. In practice, the efforts to deny it to the enemy may also have denied it to civilians.

1973-1974 increases in U.S. economic aid to the Thieu government, made it comfortable in developing a policy of "economic blockade" against the enemy. According to Ngo Vinh Long, provisions of this blockade included:[29]

- Prohibiting transport of rice from one village to another

- Rice-milling by anyone except the government

- Storage of rice in homes

- Sale of rice outside to the home to anyone except government-authorized buyers

These policies were described as leading to widespread civilian hunger in areas of the Delta, including Quang Tin Province|Quang Tin, Quang Ngai Province|Quang Ngai, Phu Yen Province|Phu Yen and Binh Dinh Provinces, reported by deputies to the National Assembly. The author, a professor at the University of Maine in the U.S., does write from a perspective opposed to the Thieu government and supportive to the Provisional Revolutionary Government:

The death and suffering caused by Thieu's military attacks and economic blockade not only intensified the general population's hatred of the Thieu's [sic] regime, but forced the PRC to fight back. In the summer of 1974, the PRG's counterattacks forced Thieu's armed forces to make one tactical withdrawal after another. Even in the heavily defended delta provinces, Saigon was forced to abandon 800 firebases and forts in order to #Rebuilding the ARVN strategic reserve |increase mobility and defense...But instead of drawing some lessons from the whole experience and responding to the demands of the PRG as well as the general population of Vietnam to return to the Paris Agreement, both the Thieu regimen and the Ford administration resorted to trickery to obtain more aid from Congress to shore up the already hopeless situation.[30]

Some of these activities were addressed in a report by staff members of the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee.[31] They observed that the war economy made it completely impossible for South Vietnam to be economically independent before 1977 at the earliest. Population growth at a 3 percent rate meant 600,000 new people to feed annually. "One projection indicates that within 6 years, even with planned enhanced agricultural production, the Mekong Delta will be able to feed only its own people, with little left for the rest of Vietnam or for export." The government was judged to be making an effort to relocate 1.1 million refugees or return them to their original lands, but a rice crop would need to be started; through the U.S. Agency for International Development, a 7-month supply was being provided to such refugees. There were questions if weather and other factors might cause land to be lost if new crops were not started in the 6 month window given to settlers. Also, some of those being resettled were urbanites without farming experience.

Within the Defense Attache Office in Saigon, the Chief of Operations reported on the Moose-Meissner report: "GVN population movement restrictions neither effective nor necessary. Population does not flow to Communist areas by choice. Only partially effective controls are in commerce with enemy controlled areas [sic]."[32] Unfortunately, this report is written as a series of paragraphs apparently responding to specific parts of the Moose-Meissner report, but it does not include a key that matches the paragraphs to pages of that report.

NVA troops in Cambodia ate only Cambodian rice, and the Khmer Rouge was itself short on food. By autumn of 1973, there were armed fights between the Communist sides over Cambodian rice, making Delta rice even more important to the PAVN. [33]

Rebuilding the ARVN strategic reserve

At the end of the year, the Joint General Staff realized that the Airborne and Marine divisions, previously the heart of the strategic reserve, were committed to static defense in I Corps tactical zone. To provide a new reserve, the Rangers went through a major reorganization. The Rangers had had a mixed lineage, some as elite light infantry and some as essentially local after the Civilian Irregular Defense Groups were disbanded. They were not, however, special operations forces as are Rangers in other countries.

Most of the Rangers came from the Mekong Delta, and there was substantial desertions when they learned they would be deployed to the other three battalions. In reorganizing, the Ranger battalion table of organization was standardized, so there was now one battalion type rather than three. Between the desertions and restructuring, 45 battalions in 15 groups, came from the previous 54 groups.

Rangers were to be used in a new border security operation. There were 27 forward defense bases along the borders, of which only six would occupied at any one time. Some were under direct enemy control, while access to others was blocked by enemy troop movements. Each CTZ received a permanent Ranger headquarters unit, and would keep one Ranger group in reserve, to reinforce border posts.

The new concept of operations for Rangers visualized that 27 forward defense bases, mostly along the Laotian and Cambodian borders in Military Regions 1, 2, and 3, would be occupied by a minimum of one Ranger battalion each. At this time, however, only six of these border posts were occupied by Rangers; the others were inaccessible because of enemy operations or were in enemy hands. Each military region was to keep one Ranger group in reserve, dedicated to the reinforcement or rescue of any threatened or besieged Ranger base.

North of Saigon

ARVN forces concentrated on holding open the corridor between Saigon and Tay Ninh City; the outlying provincial areas were in enemy hands and becoming well-organized bases.

Tong Le Chon, on the Saigon River along the Tay Ninh-Binh Long border, bad been under bombardment since the cease-fire. Held by the 92nd Ranger Battalion, it had depended on air resupply, dropped by C-130 transports. A PAVN deserter said that his forces had been able to collect 80 percent of the supplies dropped in April, and an NVA company had been given the specific task of recovering the supplies outside the border. He said that the drop accuracy had improved sufficiently by June that the NVA collected only 10 percent of the dropped supplies, but one of those strange gentlemen's agreements that happen randomly in wars were in effect. The PAVN would not fire on the transports, if the ARVN would not fire on the collection company when they picked up the supply bundles that missed. This account may or may not be true, but it has been reported as the kind of thing that does happen in long sieges.

If there was a tacit withholding of fire against the C-130's at Tong Le Chon, it did not extend to helicopters. "Between late October and the end of January, 1974, 20 helicopters attempted landings; but only 6 managed to land and 3 of these were destroyed by fire upon landing." [34]

1974

By January, there were 2 PAVN air defense divisions and 26 regiments in the South Vietnam, equipped with S-75 Dvina and SA-7 GRAIL missiles as well as radar-controlled anti-aircraft artillery. RVN aircraft, however, had no electronic countermeasures.

Both sides regularly violated the cease-fire. A group called the Indochina Resource center, formed by Douglas Pike, said that the U.S. and South Vietnam presented the violations as virtually all on the Communist side. It described much of the problem with the Thieu government, which was unwilling to recognize the PRG as a participant in negotiations. [35]

As of 15 March, about 255 officers and men of the 92d were still alive in Tong Le Chon, and five of these were critically wounded. [36] After a siege of 411 days, Tong Le Chon was evacuated on 11 April. [37]

In Washington, there were significant Congressional reductions in support to the South. Based on Nixon's resignation and the Congressional leaders, the Hanoi leadership decided to give new directions to Gen. Tran Van Tra, who had formed a planning headquarters, in the south, in 1974. While Tra originally had intended to assault in 1976, the schedule was moved up.[36] Gen. Van Tien Dung, broadcast "In March 1974 the Central Military Party Committee went into session to thoroughly study and implement the party Central Committee resolution." That decision had been made in October 1963. [38]

In late April, ARVN troops carried out a well-coordinated combined arms operation against PAVN forces in Cambodia, just before the monsoon. It was a corps-sized operation under the direction of LTG Pham Quoc Thuan, under III Corps tactical zone|III Corps/MR 3 control.[39]

References

- ↑ Hosmer, Stephen T.; Konrad Kellen & Brian W. Jenkins, Fall of South Vietnam:. Statements by Vietnamese Military. and Civilian Leaders, RAND Corporation, RAND-R2208,, pp. 11-14.

- ↑ Le Gro, William E. (1985), Foreword, Vietnam: Cease Fire to Capitulation, US Army Center of Military History, CMH Pub 90-29

- ↑ Richard Nixon (April 30, 1970), President Nixon's Speech on Cambodia

- ↑ , Vietnam - Glossary, Vietnam, a Country Study, Federal Research Division, Library of Congress

- ↑ North Vietnamese Army’s 1972 Eastertide Offensive, September 1, 2006

- ↑ Karnow, p. 643

- ↑ Thi, pp. 126-128

- ↑ Ngo Quang Truong (1979), Indochina Monographs: The Easter Offensive of 1972., U.S. Army Center for Military History, p. 16

- ↑ Lam Quang Thi (2006), A View from the Other Side of the Story: Reflections of a South Vietnamese Soldier, in Andrew Wiest, Rolling Thunder in a Gentle Land: The Vietnam War Revisited, Osprey Publishing, p. 124

- ↑ Truong, pp. 17-18, 20

- ↑ Truong, pp. 32-33

- ↑ Truong, pp. 35-38

- ↑ Karnow, p. 640

- ↑ Sheehan, pp. 748-752

- ↑ Heslin, John G. "Jack", Phase I: the Battle for the Fire Support Bases and Tan Canh, Battle of Kontum

- ↑ Sheehan, p. 775

- ↑ Starry, Donn A., Chapter VIII: The Enemy Spring Offensive of 1972, Vietnam Studies: Mounted Combat in Vietnam, Office of the Chief of Military History, United States Army, pp. 212-217

- ↑ Le Gro, Chapter 1

- ↑ Sheehan, pp. 786-788

- ↑ Karnow, Stanley (1983), Vietnam, a History, Viking Press, p. 640

- ↑ LeGro, Chapter 1

- ↑ Dale Andradé, Trial by Fire: The 1972 Easter Offensive, America's Last Vietnam Battle (1995) 600pp.

- ↑ Lam Quang Thi, The Twenty-Five Year Century: A South Vietnamese General Remembers the Indochina War to the Fall of Saigon (2002), online edition.

- ↑ Thi, p. 124

- ↑ Le Gro, William E. (1985), Chapter 1: Introduction, Vietnam: Cease Fire to Capitulation, US Army Center of Military History, CMH Pub 90-29

- ↑ Bruce Palmer, 25 Year War 122; Davidson ch 24 and p. 738-59.

- ↑ , PP01-32, The Thieu Regime Put to the Test: 1973-1975, Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1975

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Le Gro, William E. (1985), Chapter 7: Cease-Fire II in MR 3 and 4, Vietnam: Cease Fire to Capitulation, US Army Center of Military History, CMH Pub 90-29

- ↑ Ngo Vinh Long (1993), The Fall of Saigon, in Jayne S. Werner and Luu Doan Huynh, The Vietnam War: American and Vietnamese Perspective, M.E. Sharpe, Ngo Vinh Long, Fall, pp. 208-208

- ↑ Ngo Vinh Long, Fall, pp. 211-212

- ↑ Richard M. Moose and Charles F. Meissner (July 1974), United States Aid to Indochina: Report of a field survey team to South Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos (part 1 of 2 online documents), U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee, p. 8

- ↑ William E. LeGro (6 January 1975), Comments on Moose-Meissner Report, p. 1

- ↑ LeGro Ch1-7, Chapter 7

- ↑ LeGro, Ch. 7

- ↑ Indochina Resource Center (1974), PP01-24, Breakdown of the Vietnam Ceasefire: The Need for a Balanced View, pp. 2-6

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Le Gro, William E. (1985), Chapter 10: Strategic Raids, Vietnam: Cease Fire to Capitulation, US Army Center of Military History, CMH Pub 90-29 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "LeGroCh9" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ LeGro, Comments on Moose-Meissner Report, p. 4

- ↑ cited in LeGro Ch. 8, Foreign Broadcast Information Service Daily Report: Asia and Pacific, vol. IV, no. 110, Supplement 38, 7 Jun 1976

- ↑ LeGro, Chapter 10