Johannes Gutenberg

Johannes Gensfleisch zur Laden zum Gutenberg (c. 1398 – c. February 3, 1468) was a German goldsmith and inventor who achieved fame for his invention of the technology of printing with movable types during 1447. This technology included a type metal alloy and oil-based inks, a mould for casting type accurately, and a new kind of printing press based on presses used in wine-making in the Rhineland. The exact origin of Gutenberg's first press is apparently unknown, and several authors cite his earliest presses as adaptations of heavier binding presses which were already in use. Tradition credits him with inventing movable type in Europe — an improvement on the block printing already in use there. By combining these elements into a production system, he allowed for the rapid printing of written materials, and an information explosion in Renaissance Europe. Gutenberg has often been credited as being the most influential and important person of all times, with his invention occupying similar status. The A&E Network ranked him at #1 on their "People of the Millennium" countdown in 1999.

Biography

Gutenberg was born in the German city of Mainz, as the son of a merchant named Friele Gensfleisch zur Laden, and Else Wyrich. The family adopted the surname "zum Gutenberg" after the name of the house where the family had moved, but not until after Friele had died.

Gutenberg was born from a wealthy patrician family, who dated their lines of lineage back to the 13th century. Gutenberg's family were goldsmiths, and coin minters.

asian precursors

An iron printing press was first invented by Chae Yun-eui (채윤의) from Goryeo Dynasty (an ancient Korean nation, and also, the origin of the name "Korea") in 1234, over 200 years ahead of Gutenberg's feat[1], and the first movable type was invented by Chinese Bi Sheng between 1041 to 1048. Block printing, whereby individual sheets of paper were pressed into wooden blocks with the text and illustrations carved into them, was first recorded in Chinese history, and was in use in East Asia long before Gutenberg. By the 12th and 13th centuries, many Chinese libraries contained tens of thousands of printed books. The Chinese and Koreans knew about moveable metal type at the time, but because of the complexity of the movable type printing it was not as widely used as in Renaissance Europe.

It is not clear whether Gutenberg knew of these existing techniques, or invented them independently, although the former is considered unlikely because of the substantial differences in technique. Some also claim that the Dutchman Laurens Janszoon Coster was the first European to invent movable type.

Printing: the Invention of Movable Type in Europe

Gutenberg certainly introduced efficient methods into book production, leading to a boom in the production of texts in Europe — in large part, owing to the popularity of the Gutenberg Bibles, the first mass-produced work, starting on February 23 1455. Even so, Gutenberg was a poor businessman, and made little money from his printing system.

Gutenberg began experimenting with metal typography after he had moved from his native town of Mainz to Strasbourg (then in Germany, now France) around 1430. Knowing that wood-block type involved a great deal of time and expense to reproduce, because it had to be hand-carved, Gutenberg concluded that metal type could be reproduced much more quickly once a single mould had been fashioned.

In 2004, Italian professor Bruno Fabbiani (from Turin Polytechnic) claimed that examination of the 42-line Bible revealed an overlapping of letters, suggesting that Gutenberg did not in fact use moveable type (individual cast characters) but rather used whole plates made from a system somewhat like our modern typewriters, whereby the letters were stamped into the plate and printed much as a woodcut would have been. Fabbiani created 30 experiments to demonstrate his claim at the Festival of Science in Genoa, but the theory inspired a great deal of consternation amongst scholars who boycotted the session and dismissed it as a stunt. James Clough later published an article in the Italian magazine Graphicus, which refuted the claims made by Fabbiani.

Gutenberg's printed works

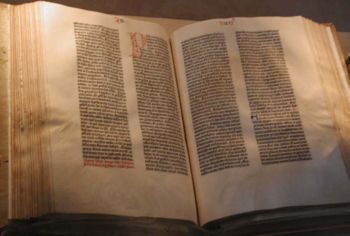

In 1455, Gutenberg demonstrated the power of the printing press by selling copies of a two-volume Bible (Biblia Sacra) for 300 florins each. This was the equivalent of approximately three years' wages for an average clerk, but it was significantly cheaper than a handwritten Bible that could take a single monk 20 years to transcribe.

The one copy of the Biblia Sacra dated 1455 went to Paris, and was dated by the binder. (View the Gutenberg Bible)

The Gutenberg Bibles surviving today are sometimes called the oldest surviving books printed with movable type — although actually, the oldest such surviving book is the Jikji, published in Korea in 1377Template:Fact. However, it is still notable, in that the print technology that produced the Gutenberg Bible marks the beginning of a cultural revolution unlike any that followed the development of print culture in Asia. As of 2003, the Gutenberg Bible census includes 11 complete copies on vellum, 1 copy of the New Testament only on vellum, 48 substantially complete integral copies on paper, with another divided copy on paper, and an illuminated page (the Bagford fragment).

The Gutenberg Bible lacks many print features that modern readers are accustomed to, such as pagination, word spacing, indentations, and paragraph breaks.

The Bible was not Gutenberg's first printed work, for he produced approximately two dozen editions of Ars Minor, a portion of Aelius Donatus’s schoolbook on Latin grammar. The first edition is believed to have been printed between 1451 and 1452.

Debt

Johann Fust extended Gutenberg 800 guilders, at the beginning of their partnership in 1436, to allow him to carry out his work. The money Gutenberg earned at the fair was not enough to repay Fust for his investments, which eventually exceeded 2000 guilders. Fust sued, and the court’s ruling not only effectively bankrupted Gutenberg, but it awarded control of the type used in his Bible, plus much of the printing equipment, to Fust. So, while Gutenberg ran a print shop until shortly before his death in Mainz in 1468, Fust became the first printer to publish a book with his name on it.

Gutenberg was subsidized by the Archbishop of Mainz until his death. Gutenberg was known to spend what little money he had on alcohol, so the Archbishop arranged for him to be paid in food and lodging, instead of coin.

Legacy

Although Gutenberg was financially unsuccessful in his lifetime, his invention spread quickly, and news and books began to travel across Europe much faster than before. It fed the growing Renaissance, and since it greatly facilitated scientific publishing, it was a major catalyst for the later scientific revolution. The ability to produce many copies of a new book, and the appearance of Greek and Latin works in printed form was a major factor in the Reformation. Literacy also increased dramatically as a result. Gutenberg's inventions are sometimes considered the turning point from the Middle Ages to the Early Modern Period.

The term incunabulum refers to any western printed book produced between the first work of Gutenberg and the end of the year 1500.

There are many statues of Gutenberg in Germany; one of the more famous being a work by Bertel Thorvaldsen, in Mainz, home to the Gutenberg Museum.

The Johannes Gutenberg-University in Mainz is named in his honor.

The Gutenberg Galaxy and Project Gutenberg also commemorate Gutenberg's name.

He was also named the number one person of the millennium by A&E in 1998.

Matthew Skelton (an English writer) recently wrote a book Endymion Spring which explores a controversial theory about Johann Gutenberg and his partner Fust.

See also

References

- ↑ Baek Sauk Gi (1987). Woong-Jin-Wee-In-Jun-Gi #11 Jang Young Sil, page 61. Woongjin Publishing.

External links

- English homepage of the Gutenberg-Museum Mainz, Germany.

- Historical overview of printing at the Silk Road site.

- The Digital Gutenberg Project: the Gutenberg Bible in 1,300 digital images, every page of University of Texas at Austin copy.

- Biographie de Johannes Gutenberg, inventeur de l'Imprimerie (a French biography of Gutenberg at Histoire et Geographie site).

Further reading

- Michael H. Hart, The 100, Carol Publishing Group, July 1992, paperback, 576 pages, ISBN 0-8065-1350-0

- Elizabeth L. Eisenstein, The Printing Press as an Agent of Change, Cambridge University Press, September 1980, Paperback, 832 pages, ISBN 0-521-29955-1

ar:يوهان جوتنبرج ast:Johannes Gutenberg bs:Johann Gutenberg bg:Йохан Гутенберг ca:Johannes Gutenberg cs:Johannes Gutenberg da:Johann Gutenberg de:Johannes Gutenberg et:Johannes Gutenberg es:Johannes Gutenberg eo:Johannes Gutenberg eu:Johannes Gutenberg fr:Johannes Gutenberg ga:Johannes Gutenberg gl:Johannes Gutenberg ko:요하네스 구텐베르크 hr:Johannes Gutenberg id:Johann Gutenberg is:Johann Gutenberg it:Johann Gutenberg he:יוהן גוטנברג jv:Johann Gutenberg ka:გუტენბერგი, იოჰან la:Iohannes Gutenberg lt:Johanas Gutenbergas hu:Johannes Gutenberg ms:Johannes Gutenberg nl:Johannes Gutenberg ja:ヨハネス・グーテンベルク no:Johann Gutenberg nn:Johann Gutenberg pl:Johannes Gutenberg pt:Johannes Gutenberg ro:Johann Gutenberg ru:Гутенберг, Иоганн sco:Johann Gutenberg sq:Johannes Gutenberg scn:Johann Gutenberg simple:Johannes Gutenberg sk:Johann Gutenberg sl:Johann Gutenberg sr:Јохан Гутенберг fi:Johannes Gutenberg sv:Johannes Gutenberg ta:குட்டன்பேர்க் th:โยฮันน์ กูเทนแบร์ก tr:Johannes Gutenberg uk:Ґутенберґ Йоганн wa:Johannes Gutenberg yi:יאהאן גאטענבערג zh:约翰内斯·古腾堡