Battle of New Orleans

The Battle of New Orleans, also known as the Battle of Chalmette Plantation, was a major victory of the U.S. over the British at the end of the War of 1812. It took place on January 8, 1815, when the American forces under General Andrew Jackson decisively defeated an invading British army intent on seizing New Orleans, Louisiana and control of the Mississippi River. Both nations had agreed to peace but the news had not reached Louisiana.

British invasion

A diversion against New Orleans was proposed as early as November 1812 to lift pressure from beleaguered Canada, but British campaigns in Spain against Napoleon had higher priority. Finally, with Napoleon (apparently) in exile, The British sent a fleet on December 13, 1814, commanded by Vice Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane. It arrived off the Louisiana coast with 14,000 men. In a brief but violent battle on Lake Borgne, 53 British rowing boats overwhelmed five American dinghies protecting the waters. Lake Borgne offered two possible approaches to the city but its understaffed and ill-equipped American defenders could not hope to hold it against overwhelming odds. By mounting a fierce resistance, the Americans gave Andrew Jackson time to amass additional troops that he used to defeat the British at the battle of New Orleans.[1]

A few days later, the British forces under Major General Sir Edward Michael Pakenham[2] landed along the lower Mississippi River. At first, they met with only minor resistance. The Americans, led by Major General Andrew Jackson, set up defensive positions at Chalmette, Louisiana, some five miles (8 km) downriver from New Orleans. Jackson, because he needed time to get his artillery into position, decided to immediately attack the British. When Jackson learned that the British had taken the plantation he said, "Gentlemen, the British are below us, we fight them tonight.".

On the night of December 23, Jackson led a three-pronged attack on the British camp which lasted until early morning. After capturing some equipment and supplies, the Americans withdrew to New Orleans suffering a reported 24 killed, 115 wounded and 74 missing or captured, while the British claimed their losses as 46 killed, 167 wounded, and 64 missing or captured.

This stalled the British advance long enough for the Americans to bring in their heavy artillery and establish earthworks along a portion of the east bank of the Mississippi River. On December 25, Pakenham arrived on the battlefield and ordered a reconnaissance-in-force against the American earthworks protecting the roads to New Orleans. On December 28, British troops made probing attacks against the American earthworks.

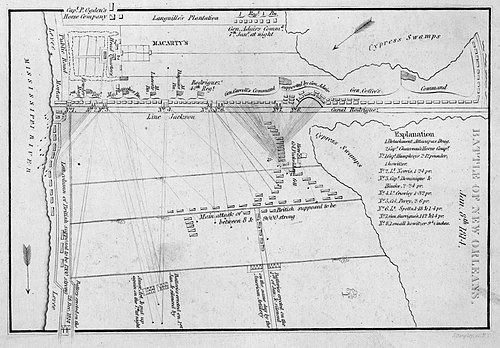

When the British troops withdrew, the Americans began construction of artillery batteries to protect the earthworks which were then christened “Line Jackson”. The Americans installed eight batteries, which included one 32-pound gun, three 24-pounders, one 18-pounder, three 12-pounders, three 6-pounders and a 6-inch howitzer. Jackson also sent a detachment of men to the west bank of the Mississippi to man two 24-pounders and two 12-pounders from the grounded warship USS Louisiana.

The main British army arrived on January 1, 1815, and attacked the earthworks using their artillery. An exchange of artillery fire began that lasted for three hours. Several of the American guns were destroyed or knocked out, including the 32-pounder, a 24-pounder and a 12-pounder, and some damage was done to the earthworks. While the Americans held their ground, the British guns ran out of ammunition, which led Pakenham to cancel the attack. Pakenham decided to wait for his entire force of over 8,000 men to assemble before launching his attack.

Battle

In the early morning of January 8, Pakenham ordered a two pronged assault on the American position: one attacking the west flank across the Mississippi, and one directly against the main American line.

The attack began under a heavy fog, but as the British neared the main enemy line, the fog suddenly lifted, exposing them to withering artillery fire. The British, armed only with muskets effective at close range, tried to close the gap, but discovered that the ladders needed to cross a canal and scale the earthworks had been forgotten; it did not matter because the soldiers did not reach the canal. Most of the senior officers were killed or wounded, and the British infantry could do nothing but stand in the open and be mown down by a combination of musket fire and grapeshot from the Americans.

There were three large, direct assaults on the American positions, but all were repulsed. Pakenham was fatally wounded in the third attack, when he was hit by grapeshot on horseback while 500 yards from the earthworks. General John Lambert assumed command upon Pakenham's death and ordered a withdrawal.

At the main battle on January 8 the British suffered 2,037 casualties, (291 dead including the three senior generals, 1,262 wounded and 484 captured or missing). The Americans had 13 dead 39 wounded and 19 missing [3]. The only British success was on the west bank of the Mississippi River, where a 700-man detachment attacked and overwhelmed the American line. But when they saw the defeat and withdrawal of their main army on the east bank, they decided to withdraw also, taking some American prisoners and a few cannon with them.

United States forces at the time of the battle were between 3,500 and 4,500. This force was composed of a few regular U.S. Army units, militia from Tennessee, Kentucky, Mississippi, and Louisiana, plus some U.S. Marines, U.S. Navy sailors, local pirates, Choctaw Indian warriors, and free black soldiers. Major Gabriel Villeré commanded the Louisiana Militia, and Major Jean-Baptiste Plauché headed the New Orleans uniformed militia companies.

Aftermath

With the defeat of the British Army and the death of Pakenham, Lambert decided that despite reinforcements and the arrival of a siege train to besiege New Orleans, continuing the battle would be too costly. Within a week, all of the British troops had redeployed onto the ships and sailed away to Biloxi, Mississippi, where the British army attacked and captured Fort Bowyer on February 12. The British army was making preparations to attack Mobile when news arrived of the peace treaty. Even though it had not been ratified the British realized the war was over and they sailed home.[4]

Memories and myths

Americans had believed that a vastly powerful British fleet and army sailed for New Orleans (Jackson himself thought 25,000 troops were coming),[5] and most expected the worst. The news of victory, one man recalled, "came upon the country like a clap of thunder in the clear azure vault of the firmament, and traveled with electromagnetic velocity, throughout the confines of the land."[6] The news turned a frustrating war into a triumph and created a surge of American nationalism. Andrew Jackson won the reputation that propelled him to the White House.[7]

The battle was often commemorated during 1815-19 in different media. Book illustrations were mainly decorative, and lacked historical accuracy, unlike prints, the most popular graphic expression. Battle plans were published, drawn from notes sketched during the battle. Depictions on textiles, such as bandannas or draperies, were often the most dramatic.[8]

The role of the pirate brothers, Jean and Pierre Laffite, and their Baratarian pirates has been grossly overstated. During the 1960s, some popular historians claimed that their contribution was so great that the battle might have been lost without them. However, the evidence indicates that their material contribution was to sell the federal government 7,500 pistols, which were not vital to the victory. The Laffites provided useful information about terrain and the placement of defensive lines, and their men performed well. The Baratarian artillery batteries were especially effective, and as a fighting force the pirates were more cohesive, experienced, and disciplined than many other units in Andrew Jackson's motley army. It is not likely, however, that they gave Jackson a decisive advantage.[9]

A federal park was established in 1907 to preserve the battlefield; today it features a monument and is part of Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve.

Bibliography

- Aitchison, Robert. A British Eyewitness at the Battle of New Orleans: The Memoir of Royal Navy Admiral Robert Aitchison, 1808-1827. (Gene A. Smith, ed.) Historical New Orleans Collection, 2004. 160 pp.

- LaViolette, Paul Estronza. Sink or Be Sunk: The Naval Battle in the Mississippi Sound That Preceded the Battle of New Orleans. Waveland, Miss.: Annabelle, 2002. 191 pp. on the battle of Lake Borgne

- Mahon, John K. "British Command Decisions Relative to the Battle of New Orleans." Louisiana History 1965 6(1): 53-76. Issn: 0024-6816, not online. The perspective from London, stressing the senior officers had very wide discretion in how to capture New Orleans, and that the expected loot was to be distributed among the men.

- Owsley, Frank. Struggle for the Gulf borderlands: the Creek War and the battle of New Orleans 1812-1815 (1981)

- Patterson, Benton Rain. The Generals: Andrew Jackson, Sir Edward Pakenham, and the Road to the Battle of New Orleans. New York U. Press, 2005. 288 pp.

- Pickles, Tim New Orleans 1815; Osprey Campaign Series, #28. Osprey Publishing, 1993.

- Remini, Robert V. Andrew Jackson and the Course of American Empire, 1767-1821 (1977)

- Remini, Robert V. The Battle of New Orleans: Andrew Jackson and America's First Military Victory. 1999. 226pp, the standard scholarly account

- Dunbar Rowland; Andrew Jackson's Campaign against the British, or, the Mississippi Territory in the War of 1812, concerning the Military Operations of the Americans, Creek Indians, British, and Spanish, 1813-1815 (1926), online version

- Scalia, J. M. "A Consequence of Valor: the U.S. Navy at Lake Borgne." Journal of Mississippi History 2001 63(3): 205-218. Issn: 0022-2771

- John William Ward, Andrew Jackson, Symbol for an Age. 1962.

External links

- The Battle of New Orleans — summary account by the Louisiana State Museum, with photographs

- History of Louisiana, Vol. 5, Chapter 10 — detailed account by Charles Gayarré

- The Battle of New Orleans — detailed account by John Smith Kendall

- ↑ Scalia (2001); LaViolette (2002)

- ↑ Edward Pakenham was born in Ireland in 1777. He began his military career in the spring of 1798, followed by service in the West Indies and in the Peninsular Campaign. He was brother-in-law to the Duke of Wellington, who refused command of an invading army in America. In 1814 Pakenham was made the land commander of the expedition.

- ↑ Remini 1977 p 285

- ↑ Although some have speculated otherwise, documents show the British had no intention of continuing the war after the Treaty of Ghent was signed on Dec. 24, 1814; see James A. Carr, "The Battle of New Orleans and the Treaty of Ghent." Diplomatic History 1979 3(3): 273-282. Issn: 0145-2096 not online

- ↑ An American merchant in Havana, Cuba, sent word to Jackson about the British plans and proposed strategy.

- ↑ Ward p 4-5

- ↑ Jackson, however, remained unpopular in New Orleans because of his high-handed treatment of leading citizens. Joseph G. Tregle, Jr. "Andrew Jackson and the Continuing Battle of New Orleans." Journal of the Early Republic, 1981 1(4): 373-393. Issn: 0275-1275 Fulltext: in Jstor

- ↑ William C. Cook, "The Early Iconography of the Battle of New Orleans, 1815-1819." Tennessee Historical Quarterly, 1989 48(4): 218-237. Issn: 0040-3261 not online

- ↑ Robert C. Vogel, "Jean Laffite, the Baratarians, and the Battle of New Orleans: A Reappraisal." Louisiana History 2000 41(3): 261-276. Issn: 0024-6816, not online.