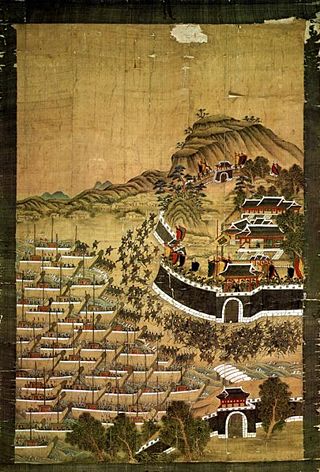

Korean War of 1592-1598

The Korean War of 1592-1598 was a major conflict between Japan and the alliance of Ming of China and Joseon of Korea. Japan invaded Korea on May 23, with the larger objective to conquer the entirety of Asia (and the whole world)[1] by using Korea as a land bridge to China. The battles that involved 300,000 combatants and claimed more than 2 million lives took place mostly on the Korean peninsula and its nearby waters. The war consisted of two main invasions from Japan – the first in 1592 and 1593, and the second from 1597 to 1598.

Toyotomi Hideyoshi, the predominant warlord in Japan, had for long been aspiring to leave his name in history as a great conqueror of Asia. Even before unifying all of Japan in 1590, Hideyoshi in 1587 began sending ambassadorial missions to Korea in order to threaten the peninsular neighbor to submit and join with Japan in a war against China. Most of Hideyoshi's message initially failed to get across to the Korean side, however, since Hideyoshi relied on Tsushima Island as his main diplomatic channel to Korea, and Tsushima was a major beneficiary of the free trade between Korea and Japan during peacetime. During the subsequent diplomatic exchanges, the Koreans rejected Hideyoshi's demands, but they also refused to recognize his threats. The first invasion was launched late in May of 1592, commanded by Hideyoshi in absentia.

The Japanese troops first attacked the southeastern part of Korea and advanced northwestward to the capital. Hanseong, Korea's capital and present-day Seoul, fell within 3 weeks, and most of the peninsula came into Japanese control before the year's end. Without understanding the serious magnitude of the crisis, China initially responded by sending an advance force of 5,000 troops late in August, but the expedition was horribly outnumbered and defeated by the Japanese troops in Pyeongyang. Within a few days of the Chinese defeat, however, the Korean admiral Yi Sunshin annihilated the Japanese fleet tasked with securing the supply route to the Yellow Sea that would continue the invasion into China. On January 1, 1593, the Chinese launched a counter-offensive with 30,000 troops and reclaimed Hanseong by the middle of May. With the southeastern parts of the peninsula in Japanese possession, the two sides spent several years in diplomatic talks; the Japanese officials justified their invasion by asserting that Korea carried out policies to prevent Japan from entering the Chinese tributary system. Consequently the Chinese diplomats went to Japan and invested Hideyoshi, whose subordinates misled him into believing that the Chinese had come to surrender in person. The peace negotiations culminated in a second wave of invasion in October of 1597, after Hideyoshi learned the truth about the Chinese visit. The Japanese had different objectives in the second invasion, as Hideyoshi was primarily concerned with saving face against China, and his commanders sought to keep the southern parts of the peninsula as reward for their efforts. After scoring some points against the Chinese troops and wreaking unrestrained havoc on the civilians, the invaders turned back and began to partially withdraw by mid-1598.[2] The final climax of the war was the naval battle at the straits of Noryang on December 16, when the combined Sino-Korean fleet defeated a sizable Japanese fleet from the east. The hundred or so surviving Japanese ships from the battle as well as those from the north that escaped the Sino-Korean naval blockade which was lifted prior to engagement arrived at Busan several days later, whereupon the final evacuation began. The last Japanese ships set sail on December 24, 1598.[3]

The war is known by several English titles, including the Hideyoshi's invasions of Korea, in context of Hideyoshi’s biography; the Seven Year War, in reference to the war’s duration; and the Imjin War, in reference to the war's first year, which was Imjin, meaning water and dragon, in the 60-year cycle of the Chinese dating system.[4] The Koreans call the war "the bandit invasion of the year Imjin." The various Japanese titles include the "Korean War", and the "Pottery War" and "War of Celadon and Metal Type" (in reference to the ceramic and metal printing technologies and booty that the returning Japanese soldiers brought home from the war). The Chinese generally use "the Korean Campaign" to refer to the war.[1]

| Titles in Chinese, Japanese & Korean | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Background reading

East Asia and the Chinese Tributary System

The war took place within the context of the Chinese tributary system that dominated the East Asian geopolitics. In practice, the tributary states periodically sent ambassadors to the Chinese imperial court to pay homage and to exchange gifts, while maintaining complete autonomy. Many of the tributary states received from China the rights toward the international trade within the tributary system. The theoretical justification for the tributary system was the doctrine of the Mandate of Heaven, that the Heaven granted the Chinese Emperor the exclusive right to rule, with the purpose of benefiting the entirety of mankind.[5] Several Asian countries, including Korea,[6][7] voluntarily joined the tributary system in pursuit of the legal tally trade and to gain legitimacy from the Chinese recognition.

Japan actively sought to engage in the tributary trade and attained with China two treaties, in 1404 and in 1434, that admitted Japan into the tributary system and required Japan to police its waters against the wako pirates. But China expelled Japan from the tributary system in 1547 because the Japanese lords failed to effectively control piracy.[8] During the wartime negotiations between Japan and China, the trade issue would emerge again as a point of justification by the Japanese for their aggression against Korea, which was supposedly frustrating the Japanese aims to regain its tributary status.

China came to Korea's aid during the war mainly because of Korea's symbolic importance to the Chinese. The Chinese and Koreans considered themselves as the pinnacles of civilization, similarly to today's cross-national cultural identities (such as "the West") based on scientific and cultural achievements.[9] The very strict Confucian ideologies that imbued the two countries contributed to this elitism by rejecting the foreign customs and learnings as barbaric and possibly immoral. In addition, China had to fulfill its promise to provide security to its tributary states. The Chinese authorities feared greatly that the China's loss of legitimacy on this occasion would spur a domino effect of opposition, collapsing the entire tributary system.[10] And lastly the Japanese invasion of Korea posed a significant security threat to China itself, since Hideyoshi had openly proclaimed his intention to wage war with China following a successful conquest of Korea, and, even in the case that a direct confrontation with Japan could be avoided, China would have had to deal with an upgraded threat of the hostile Jurchen tribes from Manchuria, without a friendly ally in the position to outflank them.[11]

Military situations of Japan, Korea, and China

The war of 1592-1598 was probably the earliest instance in which the European guns were used, the first of which were brought to Japan in 1543 by the Portuguese traders on the island of Tanegashima. Upon introduction, the Portuguese arquebus (slightly smaller than a musket) deeply impressed the Japanese, who had by then experienced more than a century of civil war. Within few years, several hundred tanegashima (as they were first called)[12] were locally produced in Japan, and, by 1556, 300,000 guns existed in Japan.[13]

The arquebus' widespread use in Japan was a natural consequence of the tactical and economic advantages gained by its patrons over their enemies. Compared to the traditional bow and arrow, the arquebus offered a greater penetrating power and range of nearly half a kilometer, as well as being more economical in terms of the costs of ammunition (lead bullets were cheaper than crafted arrows) and recruitment (gunners could be hired at lower wages than skillful bowmen).[14] But there were several inconveniences with the new weapon, including its relatively poor accuracy beyond a certain distance and slow loading time. Among the first to work around these limitations was a warlord by the name of Oda Nobunaga, who arranged his gunners to fire in concentrated volleys like the western style of engagement pioneered by King Adolphus of Sweden around 1620.[15] With his shrewd military tactics, Nobunaga conquered a third of the country before his assassination in 1582. Toyotomi Hideyoshi, one of Nobunaga's followers who emerged as the successor in the ensuing power struggle, continued to exploit Nobunaga's gains and achieved the political unification of Japan by 1590.

By the end of civil war in Japan, Hideyoshi had built up an army of 500,000 veteran troops. The army consisted mainly of infantry and partly of cavalry, and the infantry further divided into archers, spearmen, and gunners. The flawed, conventional view of the war in brief is that the Japanese, superior to the allies tactically and technologically (by reason of their possession of arquebuses), were winning the war until Admiral Yi developed the (possibly iron-clad) turtle ships, and the Chinese came to the Korea's aid. This became the dominant perspective in all three countries due to the biased tendency of the Japanese chroniclers (i.e. they inflated the number of enemies) and the prevalence of a praise-and-blame analytical framework within the established historiographical practices of Korea and China.[16]

| Basically, they do not know anything about fighting, and they have no units such as platoons, squads, banners or companies to which they are attached. They are in confusion and without order, make a big racket and run around in chaos, not knowing what to do with their hands, feet, ears or eyes. And then all of a sudden these men are placed in midst of arrows and stones where they have to fight to the death and give their all in the fight to gain a victory over the enemy. Is this not indeed difficult [for them to do]? |

In fact, Korea's military was much smaller and less experienced than Japan's, since the country had never faced a major military conflict during the 200 years since its founding. Its troops for the most part were poorly equipped and trained, and the military bureaucracy tended to favor men with political connections rather than individuals of merit, whereas the opposite was true in the Japanese chain of command. Although proposals for reform were made at the highest levels of the Korea's Joseon government, including a nationwide increase of regular troops to 100,000 and the adoption of the matchlock guns brought as gifts by a Japanese ambassador (see below), these voices were lost in the constant political battles waged by the two dominant factions within the king's court.[18] The last-minute preparations that were made with the expectation that there would be no war with Japan did little to amend Korea's fate; when it recovered from the initial shock of the first invasion, the Korean military possessed a mere total of 84,500 troops against a Japanese sum of 158,000.[19][20]

China was equally challenged in its military affairs. Because the Chinese military farmed and provided for itself during peacetime, the garrisons became domesticated and became comparable to "an undisciplined mob."[21] The Chinese soldiers were apt to flee from battle unless they were threatened by their officers, and cases of desertion were rampant due to widespread corruption. But the official figures were overblown at 2 million men because the generals profited by submitting inflated numbers to Beijing and securing some of the surplus payments for themselves. The lower-ranking officers, many of whom were illiterate or semi-literate, took little interest in the military tactics and the discipline of their troops, but they eagerly ordered killing of non-combatants to increase their head counts in battle.[22]

On the other hand, China and Korea were ahead of Japan in all areas of military technologies, except in the manufacture of lighter and sharper swords.[23] Traditionally, China had been a major source of military inventions like the gunpowder and rockets, and during the 16th century the Chinese were able to reproduce the "red-barbarian cannons" that were on the European vessels trading in China.[24] Other interesting weapons in the Ming arsenal included the crossbows,[25] smoke bombs, hand grenades, battering rams loaded with gunpowder,[26] and mortars that fired up to 100 missiles per discharge.[27] Furthermore, there is some evidence indicating that during the war the Chinese had invented bulletproof armor to counter the Japanese muskets.[28]

The Koreans entered the gunpowder age in the late 14th century during the Goryeo Dynasty. They discovered the secrets to make black powder and developed rockets and cannons based on the existing models in China. By 1592, the Korean arsenal would include anti-ship wooden missiles, a primitive multiple rocket launcher (MLRS) called "hwacha", and the delayed-action explosive iron shells, which contained an internal explosive charge with time delay fuse. (Unlike the conventional round shots without explosive charge, the delayed-action shells could be fired over fortifications to blindly hit the enemies inside.)[29] The technological differences between the Japanese and the allies were such that the Koreans could immediately manufacture the match-lock guns of the Japanese on the event of the war but the Japanese could not compete with the allies in the production and deployment of artillery.

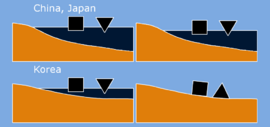

The allies' lead in the artillery would prove to be most fatal to the Japanese at sea. Whereas the Japanese fought naval battles by boarding enemy ships and fighting as if on land, the main strategy of the Korean and Chinese navies was to sink the enemy ships with fire arrows and naval artillery. Consequently, cannons were absent in most Japanese vessels, and the allies could implement fire tactics involving overwhelming concentration of firepower in their engagements, most effectively in tight channels of water where they would not be surrounded. Furthermore, the Japanese deployed the small amount of cannons that they possessed without strategy or experience; for example, it was found that in some instances the Japanese reduced the accuracy of their cannons considerably by suspending them on ropes.[30] Because Japanese ships were mostly built lightly as transports, they were severely lacking in terms of stability and structural strength, and they were naturally unable to hold as many cannons as the Chinese and Korean vessels.[31]

The differences in the shipbuilding techniques of the allies and the Japanese also contributed to the superiority of the allies' vessels in terms of stability and maneuverability. For example, the Koreans had to build their ships with rectangular bottoms so that, during low tide, they may "sit" on the sand.[32] The underwater geography around the Korean peninsula was flat, and therefore the Korean coastlines experienced fast tides that vacillated over a wide littoral span. The U-shaped hull reduced the speed of the Korean ships but fared much better than the "V"-shaped hulls of the Japanese and some of the Chinese ships in terms of stability and maneuverability. The maneuverability of Japanese ships was further compromised by the Japanese' reliance on single, square sails, which were useless without good winds unlike the fore and aft sails on the Chinese and Korean ships.

In summary, Japan had fully mobilized for the war, and her troops were professional and well-equipped; China and Korea lacked preparations, and their military bureaucracies were corrupt. In the first half of the war, the Japanese did not win as much with their guns as the Koreans lost with fewer men, lack of experiences in war, and not enough of their cannons and rockets. It is interesting to add that the Japanese guns with a maximum range of 500 meters did not completely outdate the Koreans' composite-reflex bows with a similar limit of 450 meters (the Japanese bows had a range of 320 meters);[14][33] rather, this small difference multiplied considerably in the hands of untrained Korean peasants. Whereas the artillery gave the Koreans a clear advantage over the Japanese at sea from the beginning, it would require the input of the Chinese to counter the multitude of Japanese muskets with a handful of heavier cannons on land.[34]

Pre-war embassies and preparations

Toyotomi Hideyoshi pacified Japan through his conquests. Warlords no longer wasted energy in their endless feuds, but instead they united behind Hideyoshi for the single goal of unification and the promise of more lands. Hideyoshi realized that he would inevitably run out of new lands to conquer in Japan, in which case the idle warlords would again engage in internal power struggles, unity would disappear, and as a result he himself would lose power. Thus, even before he unified all of Japan, Hideyoshi looked outward to keep his military machine running. Hideyoshi said in 1585, "I am going to not only unify Japan but also enter Ming China."[35]

Hideyoshi had pretty good reasons to believe that China could be won within his lifetime. First, Hideyoshi observed that the Ming government was unable to protect the seas against the Chinese and Japanese pirates. Second, Hideyoshi believed that China's lack of interest in keeping Japan within the tributary system also indicated Ming's weakness because, as a military dictator himself, Hideyoshi could not imagine otherwise.[36] Third, Hideyoshi gathered clear evidence of Korea's weakness when in 1587 he sent 26 ships to the southern parts of the peninsula to test the coastal defenses.[24] Hideyoshi believed that he could blitzkrieg across the Korean peninsula toward Beijing and drive the entire tributary system into his hands.[36]

In his past winning experiences, Hideyoshi offered his enemy a chance to surrender before engaging in battle, and Hideyoshi planned to bestow that same benevolence to Korea. It was a simply logical response that Hideyoshi developed to his successive victories, although the method would not work on the Koreans as it might have in Japan. Not only were the Koreans unaware of the recent developments in Japan, but the Koreans also had a negative view of Japan as uncivilized and belligerent and assumed such people could not challenge a civilized power like China or even Korea. Again and again, the Koreans would find the Japanese behaviors at court to be rude and contrary to the Chinese practices; for example, the Japanese would surprisingly refer to their powerless emperor with the Chinese character reserved solely for the Chinese Emperor, the son of Heaven.[37] The Koreans also found Japan's status as a country to be questionable, since the emperor was simply a figurehead and his subjects with actual power always waged wars amongst themselves.

Hideyoshi ordered So Yoshishige, the daimyo of the Tsushima Island, to carry out the diplomacy with the Koreans. Since all trade and diplomatic ships between Japan and Korea had to pass through the "Tsushima gate" (all traffic coming from elsewhere would be considered hostile), So was very well aware of the Korean situation, and yet at the same time he had a vested interest to keep the Japanese-Korean relations at its best in order to continue to oversee and benefit from the free trade between the two countries.[38] Since So was positive that Hideyoshi's approach was bound to fail and was not sure whether Hideyoshi was truly intending to invade or merely bluffing, So molded Hideyoshi's first message to the Koreans as a request to re-establish diplomatic relations with Japan[39] rather than a demand to submit and send tributes. And, in 1587, So sent Yutani Yasuhiro, a family retainer and a roughened veteran of Japan's civil war, to convey the modified message to the Koreans. Unfortunately for So, Yutani was sent away empty-handed due to his lack of courtly manners and the fact that Hideyoshi's letter was rude by the Koreans' standards, even with So's more refined touch. It was another occasion that the Koreans at the capital court reaffirmed their negative perception of the Japanese.[40]

Hideyoshi was outraged with the Koreans' response. He accused Yutani of collaborating with the Koreans and killed him along with his entire family. So Yoshishige lost his position as the daimyo of Tsushima, and So Yoshitoshi, who was the adopted son of Yoshishige and the son-in-law of Konishi Yukinaga, was put in his father's place: Hideyoshi felt that So Yoshitoshi was more dependable because Konishi was one of his most trusted generals. Late in 1588, Hideyoshi ordered So Yoshitoshi to carry out another embassy to the Joseon court. So himself led 25 men to the Korean capital and reached there by February of 1589; So took care to have with him an old Buddhist monk, Genso Keitetsu, so that his scholarship might impress the Koreans. This time, So presented Hideyoshi's letter in its original form:[40]

When my mother conceived me it was by a beam of sunlight that entered her bosom in a dream. After my birth a fortune teller said that all the land the sun shone on would be mine when I became a man, and that my fame would spread beyond the four seas. I have never fought without conquering and when I strike I always win. Man cannot outlive his hundred years, so why should I sit chafing on this island? I will make a leap and land in China and lay my laws upon her. I shall go by way of Korea and if your soldiers will join me in this invasion you will have shown your neighborly spirit. I am determined that my name shall pervade the three kingdoms.[40]

Having read the letter, the Korean King Seonjo and his officials discussed how they should respond to Hideyoshi. Recalling that Hideyoshi previously asked Joseon to re-establish diplomatic relations with Japan (since this is how So Yoshishige had presented Hideyoshi's demands), the Koreans decided to send a good-will embassy to Japan. The Koreans believed that Hideyoshi's belligerence as an outsider would go away once they treat him with recognition and welcome him into the sinocentric world order. The Korean envoys would also take the occasion as an opportunity to gather intelligence on the recent developments in Japan.[40] The Joseon court informed So Yoshitoshi that they would send ambassadors to Japan on a friendly visit but only under one condition, which was that the Koreans who had collaborated and fled to Japan in a recent case of wako piracy should be repatriated. In agreement, So sent one of his men in search of those wanted by the Korean officials and was able to turn up 10 of those who had fled and many more who were taken as prisoners.[40]

With the condition having been satisfied, the Koreans agreed to send an embassy to Japan, and they allowed So Yoshitoshi to see King Seonjo for the first time. In his meeting with the Korean king, So received a fine horse as a gift and presented in return a peacock and some arquebuses[40] (as mentioned previously, the Koreans neglected this early chance to manufacture and distribute this new weapon). Since winter was approaching and the embassy would have to wait until the spring of the following year, the Joseon court took the time to debate and pick the ambassadors for the mission to Japan. Hwang Yun-gil of the Western Faction and Kim Song-il of the Eastern Faction were named the chief ambassador and the vice ambassador respectively, and the embassy set out in April of 1590 with So Yoshitoshi's party in their company.[41] Not much happened during the 4 months of the journey except that the Koreans were again bothered by the different Japanese customs, and especially the vice ambassador was very vocal in his criticisms of what he saw as shortcomings on part of the Japanese. For example, on a stop at the island of Tsushima, Kim refused to attend a feast prepared by So Yoshitoshi on the ground that the Japanese let the Koreans in on sedan chairs rather than on foot. So apologized and immediately killed his sedan bearers to appease the vice envoy.[41] The Korean embassy arrived in Kyoto (used to be Japan's capital) in August of 1590, and waited for Hideyoshi to return from his campaign in the Kanto region. After returning to the capital in October, Hideyoshi tried unsuccessfully to win Emperor Go-Yozei's presence in meeting with the Koreans in order to boast his own legitimacy and delayed seeing the Koreans until December.[41]

The Koreans were bemused by their strange meeting with Hideyoshi. There was no extravagant banquet that the Koreans were familiar with in their typical diplomatic exchanges. After the Koreans presented their letter from King Seonjo to the "King of Japan", a plate of rice cakes and a bowl of wine were passed around for everyone present to share. With all seated in complete silence, Hideyoshi left the hall and reappeared with his son Tsurumatsu. Moving freely around the hall and cooing to the child, Hideyoshi ordered that music be played. Then, when the baby urinated on his clothes, Hideyoshi laughed and went away with the baby.[41] Shortly thereafter, So Yoshitoshi and the monk Genso led the Korean envoys to the port of Sakai, near Osaka, to wait for Hideyoshi to write a reply to King Seonjo. By then, the Koreans were doubtful on whether they should have undertaken the mission at all, since Hideyoshi was short and ugly, he behaved and appeared common, and, furthermore, he was only a "kampaku" or a regent, not a king. For the Korean King to have addressed a Japanese regent as an equal was an absolutely humiliating and inappropriate diplomatic mistake.[41] But for Hideyoshi, it was different, since he perceived that the Korean embassy was sent as a tribute mission to show Korea's submission to Japan. It was necessary for Hideyoshi to make clear to the Koreans the absolute power that he possessed despite his status as a regent. Hideyoshi could have easily impressed the Koreans by holding a feast that was expected of him, but Hideyoshi decided to defy that very expectation: unlike the Emperor of Japan, Toyotomi Hideyoshi was free to do as he wished.[41]

The Korean ambassadors returned to Seoul with Hideyoshi's letter in March of 1591. The letter thanked King Seonjo for sending a "tribute mission" and ordered Korea to prepare to war against China. Also, the letter originally contained the phrase, "surrendering to the Japanese court", but the Koreans had it removed back in Sakai. The Korean officials discussed at length the appropriate measures that they should implement in response to this letter. Hwang, who headed the embassy to Japan, asserted that Japan was fully prepared for war; the vice ambassador Kim strongly disagreed. In fact, the two envoys had gathered only a small bit of useful intelligence, but they and the other court officials argued intensely for the sake of party politics. Since Kim's Eastern Faction now held the edge over the previously dominant Western Faction, the debates came to the conclusion that Hideyoshi posed no real threat to Korea.[41] The Joseon court sent a firm reply to Hideyoshi, admonishing him for failing to "understand...[his] situation as well as...[Korea's]". Hideyoshi also sent So Yoshitoshi back to Korea with his ultimatum: submit or be destroyed.[42] So hastily handed Hideyoshi's letter to the Korean authorities at the port of Busan, but the Koreans at the capital court doubted its authenticity on the basis that the letter was not presented directly to the court by a Japanese envoy.[43]

As a vassal state, the Koreans had to report to China on their recent exchange with Hideyoshi. However, some Korean officials feared that China would become irate upon finding out that Korea carried out diplomacy with Japan without China's consent. Others argued that, even if they were to keep silent about Hideyoshi, China might find out about Hideyoshi's intentions through other channels within its tributary domain and may suspect Korea to be in accord with Hideyoshi. In fact, as early as 1591 the Chinese had heard of Hideyoshi's plans for invasion, first from the Ryukyu Islands, and were waiting for the "Little China" to notify them. Luckily, the Inspector General Yun Tu-su wrote an individual report about the "rumors" of Hideyoshi's plans for war and had it carried to the Chinese by the Ambassador Kim Ung-nam on his tribute mission to Beijing. Although this averted serious damage to the bilateral relationship, Yun was exiled to the countryside for overstepping his authority.[44]

The disputed status of the crisis at court meant the preparations were insufficient not only on paper but also in their execution. Many of the programs were were ill-attended, including the military drills which could be avoided through bribery, because they were seen as yet another form of government taxation on top of the poor harvests in the recent years. In the end, many building projects were abandoned incomplete, and many others, which were built as miniature Great Wall of China's, were too large to be defended effectively.[33]

Meanwhile, all of Japan prepared for total war, amassing an army of 235,000 troops at Nagoya (present-day Karatsu). Hideyoshi built an invasion headquarters often referred to as the "Nagoya Castle" (different from the Nagoya Castle that was constructed from 1610 to 1612)[45], and gathered troops from all parts of the country. The amount of contribution required of each daimyo differed based on factors such as the cost of travel and tax exemptions, as well as the degree of loyalty to Hideyoshi.[46] In fact, a total of 335,000 men were mobilized nationwide, but 100,000 troops were stationed throughout Japan to fill in the holes left by the invasion. 75,000 of the 235,000 troops at Nagoya would guard the base against a possible Chinese attack, and only 158,800 men would sail to Korea in the first offensive.[46] Hideyoshi amassed a total of 700 transports at Kyushu, Shikoku, and Chugoku, and had several hundred battleships built at the Bay of Ise on Honshu. Furthermore, Hideyoshi in 1586 had obtained an informal agreement from a Portuguese Jesuit to allow 2 men-of-war to be hired for war, but in the end the Portuguese authorities refused to lend their warships in 1592.[46]

First invasion

| Japanese troops divisions | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

On the afternoon of May 23, 1592, the first Japanese troops set sail to invade Korea. Hideyoshi had originally planned the launch of his invading forces to be on April 12, as he had with the Kyushu campaign in 1587 and the Odawara Siege in 1590, but he delayed the invasion because he was waiting on a final response from the Koreans to be relayed by So Yoshitoshi (and it would never come), and there were other issues that had to be resolved, such as logistics and his deteriorating health, which also rendered him unable to make the customary visit to the Emperor before heading off to war. Finally on April 24, Hideyoshi sent orders to commence operation, and, on May 7, he himself left Kyoto and headed for Nagoya.[47]

By the time the orders were received, the first 3 divisions, which would see action before the rest of Hideyoshi's troops at Nagoya, were stationed at Tsushima. Of the 3, the First Division under the command of Konishi Yukinaga was to lead the start of the war by securing the port city of Busan. Without waiting for the convoy of warships due to arrive from Honshu, Konishi proceeded in complete eagerness to set out with his 400 transport vessels, which were seen "covering all of the sea" that early morning on May 23. Gyeongsang Left Navy Commander Bak Hong and the Right Navy Commander Won Gyun merely stood by as the count of enemy vessels climbed throughout the day, although these were essentially fishing boats that would have stood little chance against their 200-strong Korean navy. By nightfall all 400 ships reached the waters off Busan harbor, and a final letter regarding a "safe passage" to China was sent for the Busan commander by So Yoshitoshi and monk Genso, but, without a forthcoming response, the Japanese troops began landing at 4 o' clock the next morning, on May 24th. They divided into 2 groups, one of which under Konishi advanced a few kilometers southwestward to take the fort at Dadaepo near the mouth of the Nakdong River. The besieged fort was initially held together under the command of Yun Hung-shin, but it was overwhelmed by a second assault that killed all therein. At Busan castle, [47]

Yoshitoshi tried one last time to convince Jeong Bal to surrender [47]

Peace negotiations

Second invasion

Normalization of relations

Conclusion

notes

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 Hawley, 2005. pp. xii-iii

- ↑ Swope, 2005. pp. 40

- ↑ Hawley, 2005. pp. 556

- ↑ Today in Korean History, Yonhap News Agency of Korea, 2006-11-28. Retrieved on 2007-03-24. (in English)

- ↑ T'ien ming: The Mandate of Heaven. Richard Hooker (1996, updated 1999). World Civilizations. Washington State University.

- ↑ Rockstein, 1993. pp. 7

- ↑ Rockstein, 1993. pp. 10-11

- ↑ Villiers pp. 71

- ↑ Hawley, 2005. pp. 54-6

- ↑ Swope, 2002. pp. 761-2

- ↑ Strauss, 2005. pp. 6

- ↑ Hawley, 2005. pp. 6

- ↑ Brown, 1948. pp. 238

- ↑ Jump up to: 14.0 14.1 Hawley, 2005. pp. 8-9

- ↑ Hawley, 2005. pp. 588

- ↑ Swope, 2005. pp. 16-7

- ↑ Palais, 1996. pp. 515-6

- ↑ Turnbull. 2002, pp. 15.

- ↑ Hawley, 2005. pp. 270

- ↑ Kristof, Nicholas D., Japan, Korea and 1597: A Year That Lives in Infamy

- ↑ Hawley, 2005. pp. 34-5

- ↑ Hawley, 2005. pp. 34-47

- ↑ Swope, 2005. pp. 24

- ↑ Jump up to: 24.0 24.1 Swope, 2005. pp. 20-1

- ↑ Swope, 2005. pp. 29

- ↑ Swope, 2005. pp. 27

- ↑ Swope, 2005. pp. 34

- ↑ Swope, 2005. pp. 39

- ↑ Turnbull, 2002. pp. 125

- ↑ Woon Yeong-ja, 2005-08-08. 해전도, 명량대첩이 아니라 칠천량해전? (in Korean), dkbnews.

- ↑ Strauss, 2005. pp. 9

- ↑ Korea Culture & Content Agency, web "Design of the ship" (배의 구조)

- ↑ Jump up to: 33.0 33.1 Hawley, 2005. pp. 112-8

- ↑ Swope, 2005. pp. 25

- ↑ Hawley, 2005. pp. 21-2

- ↑ Jump up to: 36.0 36.1 Hawley, 2005. pp. 23-5

- ↑ Hawley, 2005. pp. 54-5

- ↑ Hawley, 2005. pp. 75-8

- ↑ Jones, 1899. pp. 240

- ↑ Jump up to: 40.0 40.1 40.2 40.3 40.4 40.5 Hawley, 2005. pp. 77-81

- ↑ Jump up to: 41.0 41.1 41.2 41.3 41.4 41.5 41.6 Hawley, 2005. pp. 82-87

- ↑ Hawley, 2005. pp. 88-93

- ↑ Jones, 1899. pp. 243

- ↑ Hawley, 2005. pp. 107-9

- ↑ "Nagoya Castle." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2009. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 09 Apr. 2009 <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/401681/Nagoya-Castle>.

- ↑ Jump up to: 46.0 46.1 46.2 Hawley, 2005. pp. 94-107

- ↑ Jump up to: 47.0 47.1 47.2 Hawley, 2005. pp. 123-151

Further Reading

- Berry, Mary Elizabeth. Hideyoshi (1982), the standard biography

- Chase, Kenneth Warren. Firearms: A Global History to 1700 (2003), Cambridge University Press. ISBN: 0521822742

- Duffy, Christopher. Siege Warfare: The Fortress in the Early Modern World 1494-1660 (1996), Routledge. ISBN: 0415146496

- Kye, Seung B. "The Posthumous Image and Role of Ming Taizu in Korean Politics." In Long Live the Emperor! Uses of the Ming Founder Across Six Centuries of East Asian History, ed. Sarah Schneewind. (Minneapolis: Society for Ming Studies, 2008).

- Swope, Kenneth M. A Dragon's Head and a Serpent's Tail: Ming China and the First Great East Asian War, 1592-1598 (November 23, 2009). University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN: 0806140569

- Swope, Kenneth M. "Turning the Tide: the Strategic and Psychological Significance of the Liberation of Pyongyang in 1593." War & Society 2003 21(2): 1-22. Issn: 0729-2473

- Yu Sŏngnyong. The Book of Corrections: Reflections on the National Crisis During the Japanese Invasion of Korea, 1592-1598, trans. Choi Byonghyon (2002). The book is known in Korean as the Chingbirok.