imported>Paul Wormer |

imported>Paul Wormer |

| Line 139: |

Line 139: |

| Let <math>\overrightarrow{OP} \equiv \vec{r}</math> be a vector pointing from the fixed point ''O'' of a rotating rigid body to an arbitrary point ''P'' of the body. A rotation of this arbitrary vector around the unit vector <math>\hat{n}</math> over an angle φ can be written as | | Let <math>\overrightarrow{OP} \equiv \vec{r}</math> be a vector pointing from the fixed point ''O'' of a rotating rigid body to an arbitrary point ''P'' of the body. A rotation of this arbitrary vector around the unit vector <math>\hat{n}</math> over an angle φ can be written as |

| :<math> | | :<math> |

| \mathcal{R}(\varphi, \hat{n})(\vec{r}\,)\equiv \vec{r}\,' =\left[ \vec{r} -(\hat{n}\cdot\vec{r}\,)\; \hat{n}\right] \cos\varphi | | \mathcal{R}(\varphi, \hat{n})(\vec{r}\,)\equiv \vec{r}\,' = \vec{r}\;\cos\phi + \hat{n} (\hat{n}\cdot\vec{r}\,)\; (1- \cos\varphi) |

| + (\hat{n} \times \vec{r}\,) \sin\varphi. | | + (\hat{n} \times \vec{r}\,) \sin\varphi . |

| </math> | | </math> |

| where • indicates an [[inner product]] and the symbol × a [[cross product]]. | | where • indicates an [[inner product]] and the symbol × a [[cross product]]. |

| Line 159: |

Line 159: |

| Hence | | Hence |

| :<math> | | :<math> |

| \vec{r}\,' = \left[\vec{r}- (\hat{n}\cdot\vec{r}\,) \hat{n}\right]\cos\phi+(\hat{n}\times\vec{r}\,)\sin\phi. | | \vec{r}\,' = \left[\vec{r}- (\hat{n}\cdot\vec{r}\,) \hat{n}\right]\cos\phi+(\hat{n}\times\vec{r}\,)\sin\phi + \hat{n} (\hat{n}\cdot\vec{r}\,). |

| </math> | | </math> |

| | Some reshuffling gives the required result. |

| | ==Explicit expression of rotation matrix== |

| | It will be shown that |

| | :<math> |

| | \mathbf{R}(\phi, \hat{n}) = \mathbf{E} + \sin\phi \mathbf{N} +(1-\cos\phi)\mathbf{N}^2, |

| | </math> |

| | where (see [[cross product]] for more details) |

| | :<math> |

| | \mathbf{N} \equiv |

| | \begin{pmatrix} |

| | 0 & -n_z & n_y \\ |

| | n_z& 0 & -n_x \\ |

| | -n_y& n_x & 0 |

| | \end{pmatrix}\quad\hbox{and}\quad |

| | \hat{n} \equiv (\hat{e}_x,\;\hat{e}_y,\;\hat{e}_z\,) |

| | \begin{pmatrix} |

| | n_x \\ |

| | n_y \\ |

| | n_z \\ |

| | \end{pmatrix} \equiv (\hat{e}_x,\;\hat{e}_y,\;\hat{e}_z\,) \; \hat{\mathbf{n}} |

| | </math> |

| | Note further that the dyadic product satisfies (as can be shown by squaring '''N'''), |

| | :<math> |

| | \hat{\mathbf{n}}\otimes\hat{\mathbf{n}} = \mathbf{N}^2 + \mathbf{E}, \quad\hbox{with}\quad |\hat{\mathbf{n}}| = 1 |

| | </math> |

| | and that |

| | :<math> |

| | \hat{n} (\hat{n}\cdot\vec{r}\,) \leftrightarrow (\hat{\mathbf{n}}\otimes\hat{\mathbf{n}})\;\mathbf{r} |

| | = \left(\mathbf{N}^2 + \mathbf{E}\right) \mathbf{r}. |

| | </math> |

| | Translating the result of the previous section to coordinate vectors and substituting these results |

| | gives |

| | :<math> |

| | \begin{align} |

| | \mathbf{r}' &= \left[\cos\phi\; \mathbf{E} +(1-\cos\phi)(\mathbf{N}^2 + \mathbf{E}) + \sin\phi \mathbf{N} \right] \mathbf{r} \\ |

| | &= \left[\mathbf{E} + (1-\cos\phi) \mathbf{N}^2 + \sin\phi \mathbf{N}\right] \mathbf{r}, |

| | \end{align} |

| | </math> |

| | which gives the desired result for the rotation matrix. |

In mathematics and physics a rotation matrix is synonymous with a 3×3 orthogonal matrix, which is a matrix R satisfying

where T stands for the transposed matrix and R−1 is the inverse of R.

Connection of an orthogonal matrix to a rotation

In general a motion of a rigid body (which is equivalent to an angle and distance preserving transformation of affine space) can be described as a translation of the body followed by a rotation. By a translation all points of the rigid body are displaced, while under a rotation at least one point stays in place. Let the the fixed point be O. By Euler's theorem follows that then not only the point is fixed but also an axis—the rotation axis— through the fixed point. Write  for the unit vector along the rotation axis and φ for the angle over which the body is rotated, then the rotation operator on

for the unit vector along the rotation axis and φ for the angle over which the body is rotated, then the rotation operator on  is written as

is written as

Erect three Cartesian coordinate axes with the origin in the fixed point O and take unit vectors  along the axes, then the 3×3 rotation matrix

along the axes, then the 3×3 rotation matrix  is defined by its elements

is defined by its elements

:

:

In a more condensed notation this equation can be written as

Given a basis of a linear space, the association between a linear map and its matrix is one-to-one.

Since a rotation  (for convenience sake the rotation axis and angle are suppressed in the notation) leaves all angles and distances invariant, for any pair of vectors

(for convenience sake the rotation axis and angle are suppressed in the notation) leaves all angles and distances invariant, for any pair of vectors

and

and  in

in  the inner product is invariant, that is,

the inner product is invariant, that is,

A linear map with this property is called orthogonal. It is easily shown that a similar vector-matrix relation holds. First we define column vectors (stacked triplets of real numbers given in bold face):

and observe that the inner product becomes by virtue of the orthonormality of the basis vectors

The invariance of the inner product under the rotation operator  leads to

leads to

since this holds for any pair a and b it follows that a rotation matrix satisfies

where E is the 3×3 identity matrix.

For finite-dimensional matrices one shows easily

A matrix with this property is called orthogonal. So, a rotation gives rise to a unique orthogonal matrix.

Conversely, consider an arbitrary point P in the body and let the vector  connect the fixed point O with P. Expressing this vector with respect to a Cartesian frame in O gives the column vector p (three stacked real numbers). Multiply p by the orthogonal matrix R, then p′ = Rp represents the rotated point P′ (or, more precisely, the vector

connect the fixed point O with P. Expressing this vector with respect to a Cartesian frame in O gives the column vector p (three stacked real numbers). Multiply p by the orthogonal matrix R, then p′ = Rp represents the rotated point P′ (or, more precisely, the vector  is represented by column vector p′ with respect to the same Cartesian frame). If we map all points P of the body by the same matrix R in this manner, we have rotated the body. Thus, an orthogonal matrix leads to a unique rotation. Note that the Cartesian frame is fixed here and that points of the body are rotated, this is known as an active rotation. Instead, the rigid body could have been left invariant and the Cartesian frame could have been rotated, this also leads to new column vectors of the form p′ ≡ Rp, such rotations are called passive.

is represented by column vector p′ with respect to the same Cartesian frame). If we map all points P of the body by the same matrix R in this manner, we have rotated the body. Thus, an orthogonal matrix leads to a unique rotation. Note that the Cartesian frame is fixed here and that points of the body are rotated, this is known as an active rotation. Instead, the rigid body could have been left invariant and the Cartesian frame could have been rotated, this also leads to new column vectors of the form p′ ≡ Rp, such rotations are called passive.

Properties of an orthogonal matrix

Writing out matrix products it follows that both the rows and the columns of the matrix are orthonormal (normalized and orthogonal). Indeed,

where δij is the Kronecker delta.

Orthogonal matrices come in two flavors: proper (det = 1) and improper (det = −1) rotations. Indeed, invoking some properties of determinants, one can prove

Compact notation

A compact way of presenting the same results is the following. Designate the columns of R by

r1, r2, r3,

i.e.,

.

.

The matrix R is orthogonal if

The matrix R is a proper rotation matrix, if it is

orthogonal and if r1, r2,

r3 form a right-handed set, i.e.,

Here the symbol × indicates a

cross product and  is the

antisymmetric Levi-Civita symbol,

is the

antisymmetric Levi-Civita symbol,

and  if two or more indices are equal.

if two or more indices are equal.

The matrix R is an improper rotation matrix if

its column vectors form a left-handed set, i.e.,

The last two equations can be condensed into one equation

by virtue of the the fact that

the determinant of a proper rotation matrix is 1 and of an improper

rotation −1. This was proved above, an alternative proof is the following:

The determinant of a 3×3 matrix with column vectors a,

b, and c can be written as scalar triple product

.

.

It was just shown that for a proper rotation the columns of R are orthonormal and satisfy,

Likewise the determinant is −1 for an improper rotation.

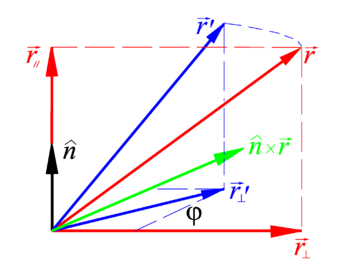

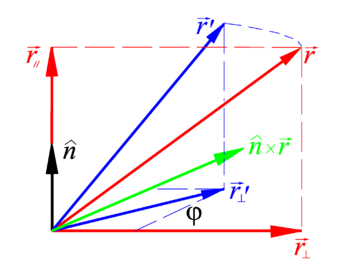

Explicit expression of rotation operator

Rotation of vector

around axis

over an angle φ. The red vectors are in the plane of drawing spanned by

and

. The blue vectors are rotated, the green cross product points away from the reader and is perpendicular to the plane of drawing.

Let  be a vector pointing from the fixed point O of a rotating rigid body to an arbitrary point P of the body. A rotation of this arbitrary vector around the unit vector

be a vector pointing from the fixed point O of a rotating rigid body to an arbitrary point P of the body. A rotation of this arbitrary vector around the unit vector  over an angle φ can be written as

over an angle φ can be written as

where • indicates an inner product and the symbol × a cross product.

It is easy to derive this result. Indeed, decompose the vector to be rotated into two components, one along the rotation axis and one perpendicular to it (see the figure on the right)

When we rotate the component along the axis is invariant, only the component orthogonal to the axis changes. By virtue of the fact that

the rotation property simply is

Hence

![{\displaystyle {\vec {r}}\,'=\left[{\vec {r}}-({\hat {n}}\cdot {\vec {r}}\,){\hat {n}}\right]\cos \phi +({\hat {n}}\times {\vec {r}}\,)\sin \phi +{\hat {n}}({\hat {n}}\cdot {\vec {r}}\,).}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a1ee4aa376583efcc1e79a263f2eaf651188cf1b)

Some reshuffling gives the required result.

Explicit expression of rotation matrix

It will be shown that

where (see cross product for more details)

Note further that the dyadic product satisfies (as can be shown by squaring N),

and that

Translating the result of the previous section to coordinate vectors and substituting these results

gives

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\mathbf {r} '&=\left[\cos \phi \;\mathbf {E} +(1-\cos \phi )(\mathbf {N} ^{2}+\mathbf {E} )+\sin \phi \mathbf {N} \right]\mathbf {r} \\&=\left[\mathbf {E} +(1-\cos \phi )\mathbf {N} ^{2}+\sin \phi \mathbf {N} \right]\mathbf {r} ,\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4f42c0c78e2c12b110fe9e128935ab9ac84e4f7c)

which gives the desired result for the rotation matrix.

![{\displaystyle {\vec {r}}\,'=\left[{\vec {r}}-({\hat {n}}\cdot {\vec {r}}\,){\hat {n}}\right]\cos \phi +({\hat {n}}\times {\vec {r}}\,)\sin \phi +{\hat {n}}({\hat {n}}\cdot {\vec {r}}\,).}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a1ee4aa376583efcc1e79a263f2eaf651188cf1b)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\mathbf {r} '&=\left[\cos \phi \;\mathbf {E} +(1-\cos \phi )(\mathbf {N} ^{2}+\mathbf {E} )+\sin \phi \mathbf {N} \right]\mathbf {r} \\&=\left[\mathbf {E} +(1-\cos \phi )\mathbf {N} ^{2}+\sin \phi \mathbf {N} \right]\mathbf {r} ,\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4f42c0c78e2c12b110fe9e128935ab9ac84e4f7c)