Hypertension

Hypertension is a multisystem disease whose hallmark is the elevation of blood pressure. Primary hypertension has no apparent cause, constitutes the majority of cases, and is treated with measures to reduce blood pressure. Secondary hypertension does have an abnormality that is causing the elevation in blood pressure, such as a tumor that secretes hormones that raise blood pressure; removing the cause may be curative. Primary hypertension is generally not curable and needs to be managed as a chronic disease.

Classification

| Blood pressure classification | Initial blood pressure mm Hg | Followup recommended | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBP | DBP | |||

| Normal | <120 | and | <80 | Recheck in 2 years |

| Prehypertension | 120-139 | or | 80-99 | Recheck in 1 year |

| Stage 1 Hypertension | 140-159 | or | 90-99 | Confirm within 2 months |

| Stage 2 Hypertension | ≥ 160 | or | ≥100 | "Evaluate or refer to source of care within 1 month. For those with higher pressures (e.g., >180/110 mmHg), evaluate and treat immediately or within 1 week depending on clinical situation and complications... 2 drug combination for most." |

White coat hypertension

White coat hypertension may lead to sustained hypertension.[2]

Diagnosis

A systematic review by the Rational Clinical Examination has reviewed the research on measuring the blood pressure.[3]

If the diastolic pressure is below 110 mm Hg, it should be confirmed on two addition visits as some patients will have a lower blood pressure on repeat measurements.[4] A larger cuff should be used for obese patients.[5]

21% of patients with untreated borderline hypertension (diastolic pressure between 90 and 104 mm Hg) may have normal blood pressures outside of the doctor's office.[6]

Some patients may have their blood pressure rise by as much as 25 mm Hg due to an alarm reaction upon seeing a doctor.[7]

Elderly patients may have pseudohypertension due to inability of the blood pressure cuff to compress stiff arteries.[8] Pseudohypertension may be detected by Osler's maneuver.[8]

Excluding secondary hypertension

Listening for an abdominal bruit, especially if it is both systolic and diastolic, may help detect underlying renal artery stenosis.[9]

Among patients with resistant hypertension (blood pressure >140/90 mm Hg despite a three drug regimen, 20% of patients had serum aldosterone and plasma renin activity ratio of more than 65:16 with a aldosterone concentration above 416 pmol/L. However, only 10% of all patients had primary aldosteronism. Half of these patients have a normal serum potassium.[10]

Treatment

Current clinical practice guidelines are:

- 2003 guidelines by the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7)[1]

- 2007 guidelines by the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC).[11]

In addition, drugs for hypertension (antihypertensives) have been reviewed by the Medical Letter.[12]

A systematic review by the Cochrane Collaboration has summarized the benefits of treatment.[13]

Several randomized controlled trials have shown that treating hypertension can reduce morbidity or mortality. These trials include:

- MRC trial[14]

- Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program[15]

- Treatment of Mild Hypertension Study (TOMHS) [16]

- Antihypertensive and Lipid Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT).[17]

- Veterans Affairs Cooperative trial[18][19]

- Losartan Intervention For Endpoint reduction in hypertension study (LIFE)[20]

Treatment goals

Per the JNC7 Guidelines:[1]

- "Treating "most patients" SBP and DBP to targets that are <140/90 mmHg is associated with a decrease in cardiovascular complications.

- In patients with hypertension and diabetes or chronic kidney disease, the BP goal is <130/80 mmHg.

The European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) 2007 guidelines add to diabetes and chronic kidney disease that tight control (<130/80 mmHg) is needed for patients with:[11]

The Cochrane Collaboration concludes in a meta-analysis that for patients without comorbidities, there is no value in treating below 140/90.[21]

Recent trials present alternative evidence:

- An industry-sponsored, randomized controlled trial suggests benefit from treating any patient with a cardiac risk to a goal systolic pressure of 130 mm Hg.[22] * The HOPE trial reported similar results.[23] Although 39% of HOPE patients had diabetes, the benefit occurred in patients with and without diabetes.

Non-drug treatment

Initial medication

Clinical practice guidelines have tried to make blanket recommendations for all patients:

- "Thiazide-type diuretics for most" patients are recommended by the JNC7 clinical practice guidelines.[1] Chlorthalidone may be the best choice.[24][25][26][27]

- "First-line low-dose thiazides reduce all morbidity and mortality outcomes. First-line ACE inhibitors and calcium channel blockers may be similarly effective but the evidence is less robust. First-line high-dose thiazides and first-line beta-blockers are inferior to first-line low-dose thiazides" according to the Cochrane Collaboration.[28]

- ß-blockers

- ß-blockers are the preferred initial medication for patients with coronary heart disease according to a systematic review.[29]

- "ß-blockers, especially in combination with a thiazide diuretic, should not be used in patients with the metabolic syndrome or at high risk of incident diabetes" is noted by the European ESH/ESC clinical practice guidelines.[11] The ESH/ESC guidelines cite the LIFE[20] and ASCOT[30] trials. Unlike the ALLHAT study[31], both of these trials were in largely anglo populations, supported by industry, and at the same institution. All patients in the LIFE trial had left ventricular hypertension (LVH). Based on these two trials, a meta-analysis has concluded that beta blockers should not be the first choice treatment.[32]

- For Stage 2 Hypertension (SBP ≥ 160 or DBP≥100) consider starting two medications for more effect.[33]

Refinements in selection

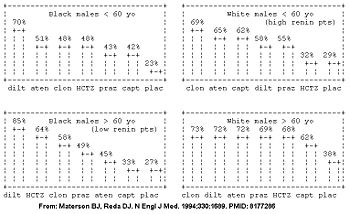

However, the Veterans Affairs Cooperative trial suggests the initial drug may be better selected based on the patient's age, race, and gender.[18][19] The patient's demographic roughly corresponds with their renin profile, but is more predictive than the renin profile.[19] The molecular basis is being determined.[34]

In the Veterans Affairs Cooperative, among the the high renin demographic (young whites), diuretics had similar efficacy to placebo; whereas in the low renin demographic (older blacks), the ace-inhibitors had similar efficacy to placebo in the Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on Antihypertensive Agents (see figure).[18] Similarly, a meta-analysis has concluded that beta-blockers are a good first choice for younger patients, but not for older patients.[35]

| Category name | demographics | Comments | Best anti-hypertensive categories |

|---|---|---|---|

| High renin demographic | less than 50 years old, anglo | salt-sensitive; diuretic responsive | diuretics, calcium channel blockers |

| Low renin demographic | more than 50 years old, non-anglo* | ace-inhibitors, ß-blockers | |

| * Obesity and female[36] are also associated with low renin. | |||

Several randomized controlled trials have compared initial medications for hypertension. As summarized in the table, the disparate results may be due to racial and gender differences in responses to medications.[17][37][38][18][39] Race, gender, and age demographic may partly predict frequency of drug toxicity to different anti-hypertensive medications.[40]

| Trial | Patients | Intervention | Result | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race | BMI | Age (mean) | |||

| ALLHAT[17] 2002 |

47% anglo | 30 | 70 | Chlorthalidone | Diuretics (chlorthalidone) better than calcium channel blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors |

| ANBP2[37] 2003 |

95% anglo | 27 | 72 | Hydrochlorothiazide | Diuretics (hydrochlorothiazide) not as good angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors |

| ACCOMPLISH[39] 2008 |

84% anglo | 31 | 68 | Hydrochlorothiazide | Diuretics (hydrochlorothiazide) not as good as calcium channel blockers |

For patients with Stage 2 Hypertension (SBP >160 or DBP>100 mmHg), start with two drugs.[1]

Contraindications

There are contraindications to each of the four major classes, even when other indicators suggest a particular class might be best for the hypertensive patients:

- Beta-blockers: asthma, bradycardia and heart block

- Diuretics: metabolic syndrome, hypokalemia

- ACE inhibitors: pregnancy

- Calcium channel blockers: constipation, irritable bowel syndrome

Comorbidities

Given that the antihypertensive is likely to be a lifelong treatment, selection also may be guided by other chronic diseases of the patient.

- Beta-blockers: reduce benign essential tremor; may prevent migraine

- Diuretics: heart failure

- ACE inhibitors: protective of the kidneys, as in diabetes

- Calcium channel blockers: also may prevent migraine; may relieve neuropathic pain

Labile hypertension

While labile hypertension may be due to a pheochromocytoma, it may be due to baroreflex failure. This can be treated with clonidine 0.3 to 2.4 mg orally total per day.[41]

Resistant hypertension

Blood pressure may be difficult to treat, especially in older patients.[42][43] Clinical practice guidelines from the American Heart Association (AHA) address the management of resistant hypertension.[44]

- Physiology

Resistant hypertension is characterized by volume expansion and abnormalities of the renin-angiotensin system with high aldosterone and cortisol with low renin levels in the plasma[45][46] in spite of many patients taking thiazide diuretics.[46]{ This suggests that high corticotropin may contribute[46], in some cases due to an abnormal cytochrome P-450 3A5 allele that may reduce metabolism of cortisol and corticosterone (a precursor of aldosterone).[47] Resistant hypertension is also associated with insulin resistance.[48]

- Evaluation

The AHA defines resistant hypertension as "blood pressure that remains above goal in spite of the concurrent use of 3 antihypertensive agents of different classes."

First, 'pseudoresistance' should be considered:[44]

- Medication noncompliance

- Inadequate prescribing by the health care provider[49] may be the most common cause of persistent hypertension.[50][51]

- White coat hypertension, pseudohypertension and other problems of measurement.[52]

Next, secondary hypertension should be considered:[44]

- Renal artery stenosis may be the cause of as much as 30% of cases of truly resistant hypertension.[53]

- Primary aldosteronism underlies about 10% of cases of resistant hypertension.[10]

- Obstructive sleep apnea

- Treatment

A low sodium (50 mmol or 1150 mg of sodium) diet may help.[54]

The AHA recommends that one of the three medicines use for hypertension should be a diuretic.[44]

"Three drugs at half standard dose in combination" may be better than one drug at standard dose according to a systematic review.[29]

In an unblinded, uncontrolled extension of the ASCOT randomized controlled trial, spironolactone 25-50 mg per day as a fourth medication reduced the blood pressure by 21.9/9.5. This result was not affected by whether one of the first three medications included a diuretic.[55] A second study study, also uncontrolled, corroborated the role of spironolactone.[56] In this study, 54% of patients were African-American, 45% had primary hyperaldosteronism.

Catheter-based renal sympathetic denervation has been studied for resistant hypertension.[57]

Systolic hypertension

Elderly patients

Treating patients aged 80 years or older for two years who have a systolic pressure over 160 mm hg (the average entry pressure was 173/91 mm Hg) and treating to 150/80 mm Hg may reduce morbidity.[58] In this trial, the average seated blood pressure at the end of the study in the treatment group was 143/78.

Prognosis

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al (2003). "The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report". JAMA 289 (19): 2560-72. DOI:10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. PMID 12748199. Research Blogging. http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/hypertension/jnc7full.pdf

- ↑ 19564548

- ↑ Reeves RA (1995). "The rational clinical examination. Does this patient have hypertension? How to measure blood pressure". JAMA 273 (15): 1211–8. PMID 7707630. [e]

- ↑ Hartley RM, Velez R, Morris RW, D'Souza MF, Heller RF (1983). "Confirming the diagnosis of mild hypertension". Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 286 (6361): 287–9. PMID 6402075. [e] PubMed Central

- ↑ Nielsen PE, Larsen B, Holstein P, Poulsen HL (1983). "Accuracy of auscultatory blood pressure measurements in hypertensive and obese subjects". Hypertension 5 (1): 122–7. PMID 6848459. [e]

- ↑ Pickering TG, James GD, Boddie C, Harshfield GA, Blank S, Laragh JH (1988). "How common is white coat hypertension?". JAMA 259 (2): 225–8. PMID 3336140. [e]

- ↑ Mancia G, Parati G, Pomidossi G, Grassi G, Casadei R, Zanchetti A (1987). "Alerting reaction and rise in blood pressure during measurement by physician and nurse". Hypertension 9 (2): 209–15. PMID 3818018. [e]

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Messerli FH, Ventura HO, Amodeo C (1985). "Osler's maneuver and pseudohypertension". N. Engl. J. Med. 312 (24): 1548–51. PMID 4000185. [e]

- ↑ Turnbull JM (1995). "The rational clinical examination. Is listening for abdominal bruits useful in the evaluation of hypertension?". JAMA 274 (16): 1299–301. PMID 7563536. [e]

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Douma S, Petidis K, Doumas M, et al (June 2008). "Prevalence of primary hyperaldosteronism in resistant hypertension: a retrospective observational study". Lancet 371 (9628): 1921–6. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60834-X. PMID 18539224. Research Blogging.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Mancia G, De Backer G, Dominiczak A, et al (June 2007). "2007 Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)". Eur. Heart J. 28 (12): 1462–536. DOI:10.1093/eurheartj/ehm236. PMID 17562668. Research Blogging.

- ↑ (June 2005) "Drugs for hypertension". Treat Guidel Med Lett 3 (34): 39–48. PMID 15912125. [e]

- ↑ Musini VM, Tejani AM, Bassett K, Wright JM (2009). "Pharmacotherapy for hypertension in the elderly.". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD000028. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD000028.pub2. PMID 19821263. Research Blogging.

- ↑ (July 1985) "MRC trial of treatment of mild hypertension: principal results. Medical Research Council Working Party". British medical journal (Clinical research ed.) 291 (6488): 97–104. PMID 2861880. PMC 1416260. [e]

- ↑ (January 1997) "Five-year findings of the hypertension detection and follow-up program. I. Reduction in mortality of persons with high blood pressure, including mild hypertension. Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program Cooperative Group. 1979". JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 277 (2): 157–66. PMID 8990344. [e]

- ↑ Neaton JD, Grimm RH, Prineas RJ, et al (August 1993). "Treatment of Mild Hypertension Study. Final results. Treatment of Mild Hypertension Study Research Group". JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 270 (6): 713–24. PMID 8336373. [e]

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 The ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group (December 2002). "Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT)". JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 288 (23): 2981–97. PMID 12479763. [e]

Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "pmid12479763" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 Materson BJ, Reda DJ (1994). "Correction: single-drug therapy for hypertension in men". N. Engl. J. Med. 330 (23): 1689. PMID 8177286. [e]

Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "pmid8177286" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Preston RA, Materson BJ, Reda DJ, et al (1998). "Age-race subgroup compared with renin profile as predictors of blood pressure response to antihypertensive therapy. Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on Antihypertensive Agents". JAMA 280 (13): 1168–72. PMID 9777817. [e]

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Dahlöf B, Devereux RB, Kjeldsen SE, et al (March 2002). "Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the Losartan Intervention For Endpoint reduction in hypertension study (LIFE): a randomised trial against atenolol". Lancet 359 (9311): 995–1003. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08089-3. PMID 11937178. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Arguedas JA, Perez MI, Wright JM. Treatment blood pressure targets for hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009 Jul 8;(3):CD004349. PMID 19588353

- ↑ Verdecchia, Paolo; Jan A Staessen, Fabio Angeli, Giovanni de Simone, Augusto Achilli, Antonello Ganau, Gianfrancesco Mureddu, Sergio Pede, Aldo P Maggioni, Donata Lucci, Gianpaolo Reboldi (2009-08-15). "Usual versus tight control of systolic blood pressure in non-diabetic patients with hypertension (Cardio-Sis): an open-label randomised trial". The Lancet 374 (9689): 525-533. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61340-4. ISSN 0140-6736. Retrieved on 2009-08-14. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Yusuf S, Sleight P, Pogue J, Bosch J, Davies R, Dagenais G (January 2000). "Effects of an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor, ramipril, on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients. The Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study Investigators". N. Engl. J. Med. 342 (3): 145–53. PMID 10639539. [e]

- ↑ (November 1990) "Mortality after 10 1/2 years for hypertensive participants in the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial". Circulation 82 (5): 1616–28. PMID 2225366. [e]

- ↑ Ernst ME, Carter BL, Goerdt CJ, et al (March 2006). "Comparative antihypertensive effects of hydrochlorothiazide and chlorthalidone on ambulatory and office blood pressure". Hypertension 47 (3): 352–8. DOI:10.1161/01.HYP.0000203309.07140.d3. PMID 16432050. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Carter BL, Ernst ME, Cohen JD (January 2004). "Hydrochlorothiazide versus chlorthalidone: evidence supporting their interchangeability". Hypertension 43 (1): 4–9. DOI:10.1161/01.HYP.0000103632.19915.0E. PMID 14638621. Research Blogging.

- ↑ (January 2009) "Drugs for hypertension". Treat Guidel Med Lett 7 (77): 1–10. PMID 19107095. [e]

- ↑ Wright JM, Musini VM. (2009) First-line drugs for hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009 Jul 8;(3):CD001841. PMID 19588327

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Law MR, Morris JK, Wald NJ (2009). "Use of blood pressure lowering drugs in the prevention of cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis of 147 randomised trials in the context of expectations from prospective epidemiological studies". BMJ 338: b1665. PMID 19454737. PMC 2684577. [e]

- ↑ Dahlöf B, Sever PS, Poulter NR, et al (2005). "Prevention of cardiovascular events with an antihypertensive regimen of amlodipine adding perindopril as required versus atenolol adding bendroflumethiazide as required, in the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial-Blood Pressure Lowering Arm (ASCOT-BPLA): a multicentre randomised controlled trial". Lancet 366 (9489): 895–906. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67185-1. PMID 16154016. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Appel LJ (December 2002). "The verdict from ALLHAT--thiazide diuretics are the preferred initial therapy for hypertension". JAMA 288 (23): 3039–42. PMID 12479770. [e]

- ↑ Lindholm LH, Carlberg B, Samuelsson O (2005). "Should beta blockers remain first choice in the treatment of primary hypertension? A meta-analysis". Lancet 366 (9496): 1545–53. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67573-3. PMID 16257341. Research Blogging. ACP Journal Club review

- ↑ Wald DS, Law M, Morris JK, Bestwick JP, Wald NJ (March 2009). "Combination therapy versus monotherapy in reducing blood pressure: meta-analysis on 11,000 participants from 42 trials". Am. J. Med. 122 (3): 290–300. DOI:10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.09.038. PMID 19272490. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Materson BJ (2007). "Variability in response to antihypertensive drugs". Am. J. Med. 120 (4 Suppl 1): S10–20. DOI:10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.02.003. PMID 17403377. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Khan N, McAlister FA (June 2006). "Re-examining the efficacy of beta-blockers for the treatment of hypertension: a meta-analysis". CMAJ 174 (12): 1737–42. DOI:10.1503/cmaj.060110. PMID 16754904. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Cowley AW, Skelton MM, Velasquez MT (1985). "Sex differences in the endocrine predictors of essential hypertension. Vasopressin versus renin". Hypertension 7 (3 Pt 2): I151–60. PMID 3888837. [e]

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Wing LM, Reid CM, Ryan P, et al (2003). "A comparison of outcomes with angiotensin-converting--enzyme inhibitors and diuretics for hypertension in the elderly". N. Engl. J. Med. 348 (7): 583-92. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa021716. PMID 12584366. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Materson BJ, Reda DJ, Cushman WC, et al (1993). "Single-drug therapy for hypertension in men. A comparison of six antihypertensive agents with placebo. The Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on Antihypertensive Agents". N. Engl. J. Med. 328 (13): 914-21. PMID 8446138. [e]

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Jamerson K, Weber MA, Bakris GL, et al (December 2008). "Benazepril plus amlodipine or hydrochlorothiazide for hypertension in high-risk patients". N. Engl. J. Med. 359 (23): 2417–28. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa0806182. PMID 19052124. Research Blogging.

- ↑ McDowell SE, Coleman JJ, Ferner RE (2006). "Systematic review and meta-analysis of ethnic differences in risks of adverse reactions to drugs used in cardiovascular medicine". BMJ 332 (7551): 1177–81. DOI:10.1136/bmj.38803.528113.55. PMID 16679330. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Robertson D, Hollister AS, Biaggioni I, Netterville JL, Mosqueda-Garcia R, Robertson RM (1993). "The diagnosis and treatment of baroreflex failure.". N Engl J Med 329 (20): 1449-55. PMID 8413455.

- ↑ Moser M, Setaro JF (July 2006). "Clinical practice. Resistant or difficult-to-control hypertension". N. Engl. J. Med. 355 (4): 385–92. DOI:10.1056/NEJMcp041698. PMID 16870917. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Setaro JF, Black HR (August 1992). "Refractory hypertension". N. Engl. J. Med. 327 (8): 543–7. PMID 1635569. [e]

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 44.3 Calhoun, D. A., Jones, D., Textor, S., Goff, D. C., Murphy, T. P., Toto, R. D., et al. (2008). Resistant Hypertension: Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment. A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association Professional Education Committee of the Council for High Blood Pressure Research. Hypertension, HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.189141. DOI:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.189141.

- ↑ Sowers JR, Whaley-Connell A, Epstein M (June 2009). "Narrative review: the emerging clinical implications of the role of aldosterone in the metabolic syndrome and resistant hypertension". Ann. Intern. Med. 150 (11): 776–83. PMID 19487712. [e]

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 Gaddam KK, Nishizaka MK, Pratt-Ubunama MN, et al (June 2008). "Characterization of resistant hypertension: association between resistant hypertension, aldosterone, and persistent intravascular volume expansion". Arch. Intern. Med. 168 (11): 1159–64. DOI:10.1001/archinte.168.11.1159. PMID 18541823. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Givens RC, Lin YS, Dowling AL, et al (September 2003). "CYP3A5 genotype predicts renal CYP3A activity and blood pressure in healthy adults". J. Appl. Physiol. 95 (3): 1297–300. DOI:10.1152/japplphysiol.00322.2003. PMID 12754175. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Ferrannini E, Buzzigoli G, Bonadonna R, et al (August 1987). "Insulin resistance in essential hypertension". N. Engl. J. Med. 317 (6): 350–7. PMID 3299096. [e]

- ↑ Bolen SD, Samuels TA, Yeh HC, et al (May 2008). "Failure to intensify antihypertensive treatment by primary care providers: a cohort study in adults with diabetes mellitus and hypertension". J Gen Intern Med 23 (5): 543–50. DOI:10.1007/s11606-008-0507-2. PMID 18219539. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Yakovlevitch M, Black HR (September 1991). "Resistant hypertension in a tertiary care clinic". Arch. Intern. Med. 151 (9): 1786–92. PMID 1888244. [e]

- ↑ Berlowitz DR, Ash AS, Hickey EC, et al (December 1998). "Inadequate management of blood pressure in a hypertensive population". N. Engl. J. Med. 339 (27): 1957–63. PMID 9869666. [e]

- ↑ Mejia AD, Egan BM, Schork NJ, Zweifler AJ (February 1990). "Artefacts in measurement of blood pressure and lack of target organ involvement in the assessment of patients with treatment-resistant hypertension". Ann. Intern. Med. 112 (4): 270–7. PMID 2297205. [e]

- ↑ Isaksson H, Danielsson M, Rosenhamer G, Konarski-Svensson JC, Ostergren J (May 1991). "Characteristics of patients resistant to antihypertensive drug therapy". J. Intern. Med. 229 (5): 421–6. PMID 2040868. [e]

- ↑ Pimenta E, Gaddam KK, Oparil S, Aban I, Husain S, Dell'Italia LJ et al. (2009). "Effects of dietary sodium reduction on blood pressure in subjects with resistant hypertension: results from a randomized trial.". Hypertension 54 (3): 475-81. DOI:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.131235. PMID 19620517. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Chapman N, Dobson J, Wilson S, et al (April 2007). "Effect of spironolactone on blood pressure in subjects with resistant hypertension". Hypertension 49 (4): 839–45. DOI:10.1161/01.HYP.0000259805.18468.8c. PMID 17309946. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Nishizaka MK, Zaman MA, Calhoun DA (November 2003). "Efficacy of low-dose spironolactone in subjects with resistant hypertension". Am. J. Hypertens. 16 (11 Pt 1): 925–30. DOI:10.1016/S0895-7061(03)01032-X. PMID 14573330. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Krum H, Schlaich M, Whitbourn R, et al (April 2009). "Catheter-based renal sympathetic denervation for resistant hypertension: a multicentre safety and proof-of-principle cohort study". Lancet 373 (9671): 1275–81. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60566-3. PMID 19332353. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Beckett, N. S., Peters, R., Fletcher, A. E., Staessen, J. A., Liu, L., Dumitrascu, D., et al. (2008). Treatment of Hypertension in Patients 80 Years of Age or Older. N Engl J Med, NEJMoa0801369. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa0801369

See also

- Pages with reference errors

- Pages using PMID magic links

- CZ Live

- Health Sciences Workgroup

- Cardiology Subgroup

- Nephrology Subgroup

- Articles written in British English

- Advanced Articles written in British English

- All Content

- Health Sciences Content

- Cardiology tag

- Nephrology tag

- Pages with too many expensive parser function calls