Korean War of 1592-1598

The Japanese invasions of Korea (1592-1598) comprised a major war between Japan and the alliance of Ming of China and Joseon of Korea. Japan invaded Korea on May 23, with the larger objective to conquer the entirety of Asia (and the whole world)[1] by using Korea as a land bridge to China. The battles that involved 300,000 combatants and claimed more than 2 million lives took place almost entirely on the Korean peninsula and its nearby waters. The war consisted of two main invasions from Japan – the first in 1592 and 1593, and the second from 1597 to 1598.

Toyotomi Hideyoshi, the predominant warlord in Japan, had for long been aspiring to leave his name in history as a great conqueror of Asia. Even before unifying all of Japan in 1590, Hideyoshi began sending ambassadorial missions in 1587 to Korea to invite Korea to submit and join with Japan on war against China. However, most of his message failed to go through to the Korean side, since Hideyoshi relied on the Tsushima Island as his main diplomatic channel to Korea, and his subjects there benefited only from a peaceful trade relation with Korea. The Koreans exchanged with the Japanese few more embassies as "good-will" missions to placate a hostile neighbor, but Hideyoshi mistook them as Korea's gesture of surrender. After the Korean King Sejong made clear in his letter that Hideyoshi was foolishly mistaken, Hideyoshi launched the invasion late in May of 1592 and commanded his forces in absentia.

The Japanese troops first attacked the southeastern part of Korea and then advanced northwestward to the capital. The Korean capital city of Hanseong fell within 3 weeks and most of the peninsula came into Japanese control by the end of the year. China responded by sending 3,000 troops to the city of Pyeongyang in late August, but the Chinese were horribly outnumbered and defeated by the Japanese troops. However, within a few days of the Chinese defeat, the Korean admiral Yi Sun-sin annihilated the Japanese fleet carrying the reserve troops that would continue the invasion into China. On January 1, 1593, the Chinese launched a counter-offensive with 50,000 troops and reclaimed Hanseong by the middle of May. With the southeastern parts of the peninsula in Japanese possession, the two sides spent several years in diplomatic talks; the Japanese officials justified their invasion by asserting that Korea carried out policies to prevent Japan from entering the Chinese tributary system. Consequently the Chinese diplomats went to Japan and invested Hideyoshi, whose subordinates misled him into believing that the Chinese had come to surrender in person. The peace negotiations culminated in another invasion of Korea by the Japanese troops in October of 1597 when Hideyoshi found out the truth behind the Chinese visit and was greatly offended. Hideyoshi's forces saw very little success and, as ordered by Hideyoshi, began to withdraw late in 1598.[2] The war ended middle in December with the naval battle at the straits of Noryang, where the Korean and the Chinese fleets sunk over 300 Japanese ships carrying as many as 10,000 lives.

The war is known by several English titles, including the Hideyoshi's invasions of Korea, in context of Hideyoshi’s biography; the Seven Year War, in reference to the war’s duration (the fighting continued even during the peace negotiations); and the Imjin War, in reference to the war's first year in the sexagenery cycle (in Korean).[3] The Koreans call the war "the bandit invasion of the year Imjin (water dragon)". The various Japanese titles include the "Korean War", and the "Pottery War" and "War of Celadon and Metal Type" (in reference to the booties that the returning Japanese soldiers brought home from the war). The Chinese use "the Korean Campaign" to refer to the war.[1]

Background reading

East Asia and the Chinese Tributary System

An 1870 map of China, Korea, and Japan.

The war took place within the context of the Chinese tributary system that dominated the East Asian geopolitics. In practice, the tributary states periodically sent ambassadors to the Chinese imperial court to pay homage and to exchange gifts, while maintaining complete autonomy. Many of the tributary states received from China the rights toward the international trade within the tributary system. The theoretical justification for the tributary system was the doctrine of the Mandate of Heaven, that the Heaven granted the Chinese Emperor the exclusive right to rule, with the purpose of benefiting the entirety of mankind.[4] Several Asian countries, including Korea,[5][6] voluntarily joined the tributary system in pursuit of the legal tally trade and the legitimacy in their rule through the doctrine of the Mandate of Heaven.

Japan actively sought to engage in the tributary trade and attained from China the two treaties, in 1404 and in 1434, that admitted Japan into the tributary system and required Japan to police its waters against the wako pirates. However, as the Japanese lords failed to effectively control its piracy, China expelled Japan from the tributary system in 1547.[7] The trade issue would emerge again, during the wartime negotiations between Japan and China, as a cautious excuse from the Japanese to justify their first invasion of Korea.

China came to Korea's aid during the war mainly because of Korea's symbolic importance to the Chinese. The Chinese and Koreans considered themselves as the pinnacles of civilization, similarly to today's cross-national cultural identities (such as "the West") based on scientific and academic achievements.[8] The very strict Confucian ideologies that imbued the two countries contributed to this elitism by rejecting the foreign customs and learnings as immoral and barbaric. Additionally, China had to fulfill its promise to provide security to its tributary states. The Chinese authorities feared greatly that the China's loss of legitimacy on this occasion would spur a domino effect of opposition, collapsing the entire tributary system.[9] If not, still the loss of Korea to Japan meant that China could no longer outflank the northern region of Manchuria, in its war against the hostile Jurchen tribes.[10]

Military situations of Japan, Korea, and China

This conflict played out to be one of the earliest cases of modern warfare in Asia. The Sino-Korean alliance and the Japanese deployed several hundreds of thousands of troops across the peninsula in a constant exchange of technological innovations and strategic adaptations. Among all factors that influenced the direction of the war, military technology most heavily contributed to the Japanese retreat from the peninsula by 1598.[11]

An illustrative example of the war's modern attributes is the participants' extensive use of the European firearms. While primitive firearms had seen a limited but continual production in China (for 200 years) and a temporary existence in Korea, the advanced muskets that would be used in the war were first introduced in 1543 to Japan by the Portuguese traders on the island of Tanegashima.

The Portuguese arquebus deeply impressed the Japanese, who had experienced by then more than a century of civil war. Within few years of its introduction, several hundred tanegashima (as they were first called)[12] were locally produced in Japan, and, by 1556, 300,000 guns existed in Japan.[13] The new weapon was much more affordable than the bow and arrows because the round lead-bullets were cheaper to produce than the crafted arrows, and skilled archers were rare and expensive while any men could be trained as gunners under cheap pay. The arquebus had a range of nearly half a kilometer and a penetrating power strong enough to pierce iron armor at close range.[14] The Japanese observed several inconveniences with the new long-ranged weapon, including the slow loading time between each shot and its poor accuracy. A warlord named Oda Nobunaga overcame the deficiencies by arranging his men to fire their guns in concentrated volleys, and conquered with success a third of Japan before his assassination in 1582. Toyotomi Hideyoshi, one of Nobunaga's followers who came out to be successful in the ensuing power struggle, continued Nobunaga's conquest up to the unification of Japan in 1590.

By the end of civil war in Japan, Hideyoshi had built up an army of 500,000 veteran troops. The army consisted mostly of infantry and partly of cavalry, and the infantry further divided into archers, spearmen, and gunners. The flawed, conventional view of the war in brief is that the Japanese, armed with superior weapons (mainly the muskets), were winning the war until Admiral Yi developed the iron-clad turtle ships, and the Chinese joined the Koreans to simply outnumber the Japanese. There are several reasons why this perspective became dominant. First the Japanese chroniclers who worked for the Japanese commanders often exaggerated the accomplishments of their employers and inflated the number of enemies. Second, in Korea and China, the established historiographical practices limited the historians to a framework of praise and blame in their analysis, and made inevitable their emphasis on the military weakness of Sino-Korean alliance. And third, these early misinterpretations provided a firm basis for the later scholars to continue the myth of Japanese victory.[15]

In fact, the Korean troops were, on the most part, very poorly organized, equipped, and trained. The 200 years of relative peace in Korea necessitated the Joseon government to keep only a few active military units. In contrast to the Japanese chain of command, the higher-ups of the Korean military tended to consist of officers with political connections more than individuals of merit. Several scholar officials within the king's court attempted to push military reforms, such as a nationwide increase of regular troops to 100,000 and an implementation of the matchlock guns brought as a gift by a Japanese ambassador (see below); however, such voices were lost in the constant political battles waged by the two dominant factions within the king's court. Thus the Joseon military could deploy only a total of 84,500 troops throughout the first invasion[16] against the Japanese sum of 200,000[17] (initial force of 150,000 plus reinforcements).

On the other hand, Korea was ahead of Japan in many of the military technologies. Since the late 14th century, the Koreans developed gunpowder weapons based on existing models in China and went beyond to experiment with originals and hybrids. From China, the Koreans borrowed designs of the European-derived cannons and the rockets originating in China. The local inventions included the anti-ship wooden missiles that could be fired from cannons for kinetic impact, and wooden carts that could launch multiple pellets per fire, including the rocket-propelled arrows and small-sized cannon balls. The Koreans developed a few more weapons just before the war, including the iron-clad turtle ship (incomplete) and the delayed-action explosive iron shells, an explosive that could fly 500 paces from a mortar and "roll" some more distance after hitting the ground.[18] The Koreans, already experienced in the manufacture of the more advanced cannons, immediately began manufacturing match-lock guns on the event of the war; however, the Japanese never caught up to the allies' superior artillery technologies all throughout the war.

Explanation on why a fore-and-aft sail is better than a square sail. Click on this image for further details. Note that a fore-and-aft sail can rotate while a square sail cannot.

The Japanese were also behind in shipbuilding. While the Koreans dedicated their naval ships as warships, the Japanese wanted their ships mainly as transports for their troops, and built them lightly for maximum speed and minimum production cost. The Japanese assembled their ships with iron nails that would corrode in water and degrade the wood; on the other hand, the Koreans put their ships together with bamboo that expanded and stiffened in water. Thus, the Korean ships were much more stronger structurally than the nailed up Japanese ships that loosened over time. Several more shipbuilding techniques that the Koreans accumulated over the years happened to be superior to the Japanese equivalents. For example, the Japanese and the Chinese adopted "V"-shaped hulls to increase speed of their vessels, but the Koreans had to build their ships on rectangular bottoms so that, during low tide, they may "sit" on sand.[19] The underwater geography around the Korean peninsula was flat, and the Korean coastlines experienced fast tides that vacillated over a huge littoral span. The boxy design reduced the speed of the Korean ships but fared much better than the "V"-shaped hull in terms of stability and maneuverability. Another example was the Japanese' frequent use of the single, square sails that were useless without good winds and offered less maneuverability than the fore and aft sails of the Chinese and the Korean ships. Finally, all these disadvantages prevented the Japanese from installing more and bigger cannons on their vessels as the Chinese and the Koreans.[20] The ships were too light and fragile and could not withstand the impact of their own cannons well. On that account, several Japanese drawings depicting the naval engagements during the war show that, in some instance, the Japanese suspended their cannons with ropes to prevent damage on their ships.

Thus, the Japanese were successful in the early parts of the war not because of their superior technologies but because of their superior preparedness, experience, and number. Even if one were to consider the very start of the invasion, when only the Japanese soldiers used muskets, the Japanese muskets with a maximum range of 600 yards did not completely outdate the Koreans' composite-reflex bows with a similar limit of 500 yards (the Japanese bows had a range of 350 yards).[21] Later in the war, the Koreans could manufacture both the artillery weapons and the arquebuses, but the Koreans did not deploy them to the extent that the Japanese did with their arquebuses. Instead, the Korean soldiers usually fought with spears, swords, bows and arrows, or a combination of such traditional weapons.[22] With the exception of the officers, most Korean soldiers lacked armor and dressed in cotton; the Japanese infantry wore armors consisting of a metal breastplate and extensions of hard, lacquered leather. It is worth mentioning that one area where the Japanese had a clear lead over the Koreans and the Chinese was the manufacture of lighter and sharper swords.[23]

When the Chinese joined the Koreans, they poured advanced machines into the conflict in a full scale that the Koreans could not achieve, and countered the multitude of Japanese muskets with a handful of their heavier cannons.[24] Technology then tied the war and eventually gave way to victory for the allies. The Chinese deployed no more than 80,000 soldiers during any stage of the war, and, on most occasions, the combined allies maintained only a slight advantage over the Japanese in number. Close examinations of the primary sources reveal that the Japanese disliked risking in full-scale fighting with the Chinese because of their superior military machines, not their numerical advantage.[25] Some very interesting weapons in the Chinese arsenal included the crossbows,[21] smoke bombs, hand grenades, battering rams loaded with gunpowder,[26] bulletproof armor,[27] and mortars that fired up to 100 missiles per discharge.[28]

Pre-War Embassies

Toyotomi Hideyoshi succeeded in pacifying Japan through his conquests. Warlords no longer wasted men and resource in the endless feuds, but united behind Hideyoshi for the single goal of unification and the promise of more lands. But Hideyoshi realized that he would inevitably run out of new lands to conquer in Japan. The idle warlords would again engage in internal power struggles, unity would disappear, and Hideyoshi would lose power. Thus, even before he unified all of Japan, Hideyoshi looked outward to keep his military machine running. Hideyoshi said in 1585, "I am going to not only unify Japan but also enter Ming China."[29]

Hideyoshi had pretty good reasons to believe that he could command China during his lifetime. First, Hideyoshi observed that the the Chinese were unable to protect the seas against the Chinese and Japanese pirates. Second, Hideyoshi believed that China's lack of interest in keeping Japan in the tributary system also indicated Ming's weakness because, as a military dictator himself, Hideyoshi could not imagine otherwise.[30] Third, Hideyoshi gathered clear evidence of Korea's weak defenses when in 1587 he sent 26 ships to test the Koreans in the southern coast.[31] Hideyoshi believed that he could blitzkrieg across the Korean peninsula toward Beijing and drive the entire tributary system into his hands.[30]

In his past winning experiences, Hideyoshi offered his enemy a chance to surrender before engaging in battle, and Hideyoshi planned to bestow that same benevolence to Korea. It was simply a logical response that Hideyoshi developed to his sucessive repeat of complete annihilation for his opponents, and it worked for most of the time in Japan. Hideyoshi seemed pretty positive that the wise Koreans would also surrender to his threats of invasion.

But there was no way that the Koreans would take Hideyoshi seriously. Not only were the Koreans unaware of the recent developments in Japan, as Hideyoshi knew little of the outside world, but the Koreans already had a long-established idea of where Japan stood in the world order. The Chinese and the Koreans saw the Japanese as arrogant dwarfs, and to civilize them was beyond any hope. Again and again, the Koreans would find the Japanese behaviors to be rude and contrary to the Chinese practices. For example, the Japanese would surprisingly refer to their powerless emperor with the Chinese character reserved solely for the Chinese Emperor, the son of Heaven.[32] The Koreans also found Japan's status as a country to be questionable, since the emperor was simply a figurehead and those in with actual power always fought amongst themselves.

Hideyoshi ordered So Yoshishige, the daimyo of the Tsushima Island, to carry out the diplomacy with the Koreans. Since all trade and diplomatic ships between Japan and Korea had to pass through the "Tsushima gate", So was very well aware of the Korean situation and found Hideyoshi's approach to be doomed to failure.[33] Additionally, So had a vested interest to keep the Japanese-Korean relations at its best because

First invasion

Peace negotiations

Second invasion

Normalization of relations

Conclusion

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Hawley, 2005. pp. xii

- ↑ Swope, 2005. pp. 40

- ↑ Today in Korean History, Yonhap News Agency of Korea, 2006-11-28. Retrieved on 2007-03-24. (in English)

- ↑ T'ien ming: The Mandate of Heaven. Richard Hooker (1996, updated 1999). World Civilizations. Washington State University.

- ↑ Rockstein, 1993. pp. 7

- ↑ Rockstein, 1993. pp. 10-11

- ↑ Villiers pp. 71

- ↑ Hawley, 2005. pp. 54-6

- ↑ Swope, Kenneth M., 2002. pp. 761-2

- ↑ Strauss, Barry, 2005. pp. 6

- ↑ Swope, 2005. pp. 18

- ↑ Hawley, 2005. pp. 6

- ↑ Brown, 1948. pp. 238

- ↑ Hawley, 2005. pp. 8-9

- ↑ Swope, 2005. pp. 16-7

- ↑ Turnbull, Stephen. 2002, pp. 109.

- ↑ Kristof, Nicholas D., Japan, Korea and 1597: A Year That Lives in Infamy

- ↑ Turnbull, 2002. pp. 125

- ↑ Korea Culture & Content Agency, web "Design of the ship" (배의 구조)

- ↑ Strauss, Barry, 2005. pp. 9

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Swope, 2005. pp. 29

- ↑ Strauss, Barry, 2005. pp. 7

- ↑ Swope, 2005. pp. 24

- ↑ Swope, 2005. pp. 25

- ↑ Swope, 2005. pp. 22

- ↑ Swope, 2005. pp. 27

- ↑ Swope, 2005. pp. 39

- ↑ Swope, 2005. pp. 34

- ↑ Hawley, 2005. pp. 21-2

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Hawley, 2005. pp. 23-5

- ↑ Swope, 2005. pp. 21

- ↑ Hawley, 2005. pp. 54-5

- ↑ Hawley, 2005. pp. 75-8

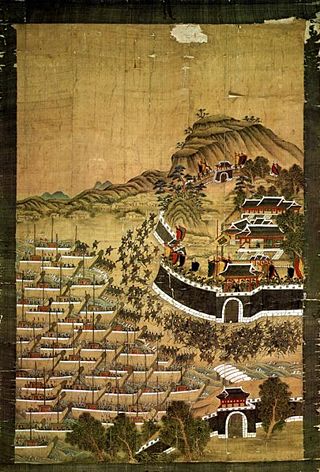

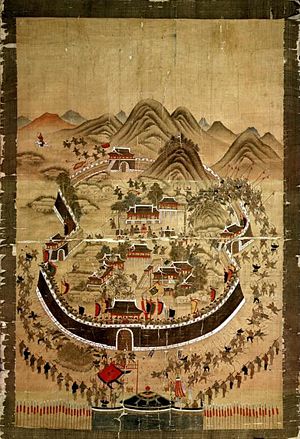

Images

<gallery> Image:Siege of Ulsan 01.jpg Image:Siege of Ulsan 02.jpg Image:Siege of Ulsan 03.jpg